Colostrum

The feeding of an adequate volume of good quality, clean colostrum as soon as possible after birth is arguably the most significant effect a farmer can have on the life of a cow. Providing simple straightforward colostrum protocols of quality, quantity, quickly and squeaky clean should enable this focus. They are inexpensive, do not take significant amounts of time and are very effective at reducing morbidity and mortality. The ability to then develop programmes to routinely monitor colostrum management and measure success becomes hugely rewarding to all involved.

Good colostrum management is the cornerstone of successful calf-rearing (Potter, 2011) (Figure 1). Calves receiving adequate colostrum have reduced risk for pre-weaning morbidity and mortality, with additional long-term benefits:

- Reduced risk of mortality in the post-weaning period

- Improved rate of gain and feed efficiency

- Reduced age at first calving

- Improved first and second lactation milk production

- Reduced risk of culling in the first lactation (Godden, 2008).

Colostrum contains immunoglobulins that protect the calf from the wide range of diseases that its mother has been exposed to during her recent life. It is highly nutritious — it contains approximately five times the normal proteins, and twice the fat of normal milk and a wide selection of minerals and vitamins which are greatly raised to over 10 times that found in normal milk (Godden, 2008). It is generally considered to be important for getting the calf warmed up and moving around soon after birth (Blowey, 1999), and for maintenance and growth. It contains the first water a calf receives. The fat content of colostrum, as well as being an energy source, acts as a laxative and assists in the passage of meconium (Blowey, 1999).

In addition, colostrum has very high levels of leukocytes, plus several other factors that stimulate the newborn's immune system (growth factors, hormones, vitamins and minerals) (Barrington and Parish, 2001). It stimulates the production of acid and digestive enzymes when it enters the abomasum; at 2 to 3 days old the abomasum has a pH 3–4. This acid kills many ingested bacteria and is therefore a very important defence mechanism (Blowey, 1999).

Hormones and growth factors in colostrum are responsible for determining the expression of certain genes involved with weight gain, mammary development, development of the digestive tract and development of the reproductive tract — this is known as epigenetic programming.

Colostrum is very different to milk (Table 1), being nearly twice as concentrated (23.9% vs. 12.5%). There are much higher levels of fat in colostrum compared with milk and much higher levels of protein, especially immunoglobulins (67 times greater in colostrum vs. milk) (Davis and Drackley, 1998).

Table 1. Characteristics and composition of Holstein colostrum and milk

| Factor | 1 | 2 | 3 | Milk |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Solids (%) | 23.9 | 17.9 | 14.1 | 12.5 |

| Fat(%) | 6.7 | 5.4 | 3.9 | 3.6 |

| Solids not fat (%) | 16.7 | 12.2 | 9.8 | 8.6 |

| Total protein (%) | 14.0 | 8.4 | 5.1 | 3.2 |

| Casein (%) | 4.8 | 4.3 | 3.8 | 2.5 |

| Albumin (%) | 0.9 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 0.5 |

| Immunoglobulins (antibodies) (%) | 6.0 | 4.2 | 2.4 | 0.09 |

| Lactose (%) | 2.7 | 3.9 | 4.4 | 4.9 |

| Calcium (%) | 0.26 | 0.15 | 0.15 | 0.13 |

| Vitamin A (µg/100ml) | 295 | 190 | 113 | 34 |

| Vitamin E (µg/g fat) | 84 | 76 | 56 | 15 |

| Vitamin B12 (µg/100ml) | 4.9 | - | 2.5 | 0.6 |

In the uterus, the cow and calf blood supplies are separated by the placenta. This prevents transmission in the uterus of immunoglobulins from the cow to the calf, so that the calf is born agammaglobulinaemic (Arthur et al, 1996). The calf therefore depends almost entirely on absorption of immunoglobulins from colostrum after birth (Godden, 2008). Absorption of these immunoglobulins across the calf's small intestine during the first 24 hours after birth is called transfer of passive immunity, and helps protect the calf against disease until its own immature immune system becomes functional.

Failure of passive transfer (FPT) of maternal immunity occurs when a calf fails to absorb an adequate quantity of immunoglobulins (Beam et al, 2009). FPT is not a disease, but a condition that predisposes the newborn calf to the development of disease (Weaver et al, 2000). Estimated prevalence of FPT in US dairy heifers is 19.2% (Beam et al, 2009); with 31% of deaths in the first 3 weeks due to FPT (Wells et al, 1996). In Scotland the mean proportion of calves with FPT is much higher at 46.6% (Denholm and Haggarty, 2019). In the UK MacFarlane et al (2015) found 26% of calves with FPT measured at serum total protein (TP) less than 5.6 mg/ml.

Effective colostrum management is the cornerstone of a good calf rearing programme. When it comes to colostrum management the focus must be on five key areas: Quality, Quantity, Quickly, sQueaky clean and Quantify (Tilling, 2014).

Quality

Good quality colostrum has high levels of immunoglobulins in it. Concentration of immunoglobulins in colostrum can vary considerably between individual cows. For every 10 g/litre increase in colostrum IgG concentration, serum IgG in a calf fed that colostrum increases 1.1g/litre (Shivley et al, 2018). Concentration is highest in colostrum immediately after calving; it then decreases by 3.7% during each subsequent hour post calving (Moring et al, 2010). Time of first milking is therefore the most crucial factor regarding colostrum quality that farmers can influence (Lorenz et al, 2011).

Other factors under the farmer's control that affect colostrum quality include:

- Dry cow nutrition — feeding dry cows and heifers balanced non-lactating rations, with a suitable transition period

- Vaccination during dry period — to increase colostral immunoglobulins versus common infections the calf may encounter e.g. rotavirus, coronavirus, Escherichia coli, Salmonella Dublin and Salmonella Typhimurium

- Stressors — reducing stress the cow is under for example heat stress. Reducing stress in the heifer, for example by having her on the farm in a relaxed setting at least 2 months before calving

- Length of dry period — cows with excessively long dry periods (>90 days), short dry periods (<21 days) or no dry period, produce colostrum with significantly lower immunoglobulin concentrations (Rastani et al, 2005)

- Pooling colostrum — low immunoglobulin, high-volume colostrum will be over-represented in any pooled colostrum (Weaver et al, 2000). The use of pooled colostrum increases the risk of FPT by 2.2 fold (Beam et al, 2009).

Several other factors will have a bearing on colostrum quality, beyond the control of the farmer:

- Beef breeds produce better quality colostrum than dairy, however this does not mean colostrum management should be taken for granted in beef herds

- Older cows having greater exposure to on-farm pathogens produce higher quality colostrum than young cows

- Dilution effects of high yielding cows can lead to poorer quality colostrum — if more than 8.5 litres is harvested the quality is likely to be poor (Weaver et al, 2000).

- Sick cows suffering mastitis or milk fever inevitably produce poorer quality colostrum (Maunsell et al, 1998).

The most frequently used instrument to test colostrum quality is the colostrometer (Figure 2). It is colour coded to provide guidance in colostrum selection. Assessment of colostrum quality with the colostrometer can be used as the basis of identifying situations where colostrum supplementation or replacement is required, as well as identifying good-quality colostrum suitable for storage (Potter, 2011)(Figure 3).

Many farmers now use Brix refractometers to assess colostrum quality. Brix refractometry is traditionally used in the wine, sugar, fruit juice and honey industries, and is a measure of sucrose in a sucrose containing solution. When used in non-sucrose-containingliquids, e.g. colostrum, Brix percentage approximates total solids percentage (Quigley et al, 2013). McGuirk and Collins (2004) found 22% to equate to 50 g of antibody/litre, and this is taken as the target. MacFarlane et al (2015) found that colostrum quality ranged from 10–34% on the Brix refractometer. As with other refractometers the test solution (colostrum) is placed on the glass surface and a scale read through the eye piece: <20% poor, 20–22% okay, >22% good. Brix is therefore objective and temperature independent (particularly when compared with a colostrometer). Evaluation of colostrum can also be done at cow side, making it easy to implement management decisions based on test results (Quigley et al, 2013).

Hart (2014) found 40% of UK colostrum samples were below the target of Brix score 22%. Donlon et al (2018) found similar results in Irish dairy herds, with 39% of samples of poor quality. Atkinson (2015) found that only 20% of farmers regularly (at least half of the time) measured colostrum quality, and fewer than 10% of farmers harvested the colostrum in the calving pen, but instead waited until the next milking, with an average time of 8 hours 40 minutes between calving and harvesting colostrum (Atkinson, 2015) — the optimum time for collection is as soon as the cows calves. With such high incidence of poor colostrum quality, and a low rate of harvesting quickly enough, greater emphasis needs to be put on farmers to measure colostrum quality.

Quantity

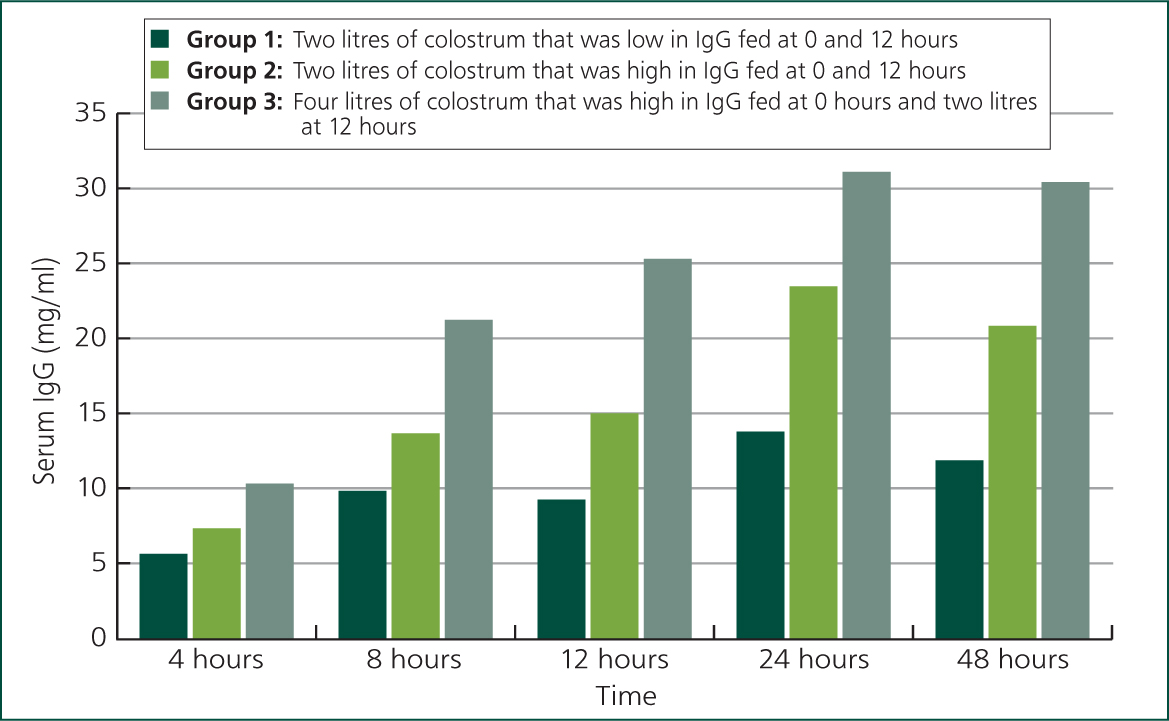

The most important factor determining successful passive transfer of maternal immunity is the quantity of colostrum ingested or administered to the calf. Dairy calves left with their mother will not ingest an adequate volume of the relatively dilute dairy cow colostrum to meet their immunoglobulin requirements (Weaver et al, 2000). Because the concentration of immunoglobulins in the colostrum being fed is not known, it is currently recommended that calves be fed 10–12% of their bodyweight of colostrum at first feeding (Godden, 2008). For a dairy calf this is approximately 4 litres (Figure 4).

Leaving the calf with its mother not only makes it difficult to determine colostrum intake but also increases the risk of infection. Calves left with their mother have a 2.4 times greater risk of FPT compared with hand feeding (Beam, 2009). Removing the calf as soon as possible from the dam and feeding 4 litres of the mother's colostrum with either a nipple bottle or oesophageal tube (Figures 5 and 6) ensures confidence that the calf has received an appropriate quantity of colostrum. No difference has been found in absorption of IgG from colostrum when feeding good quality colostrum through either an oesophageal tube or nipple bottle (Desjardins-Morrissette et al, 2018). Ensuring that 4 litres of colostrum is fed as soon as possible after birth is a simple and reliable method to achieve concentrations of immunoglobulins in calves that are above the desired value of 10 g/litre (Lorenz, 2008).

Quickly

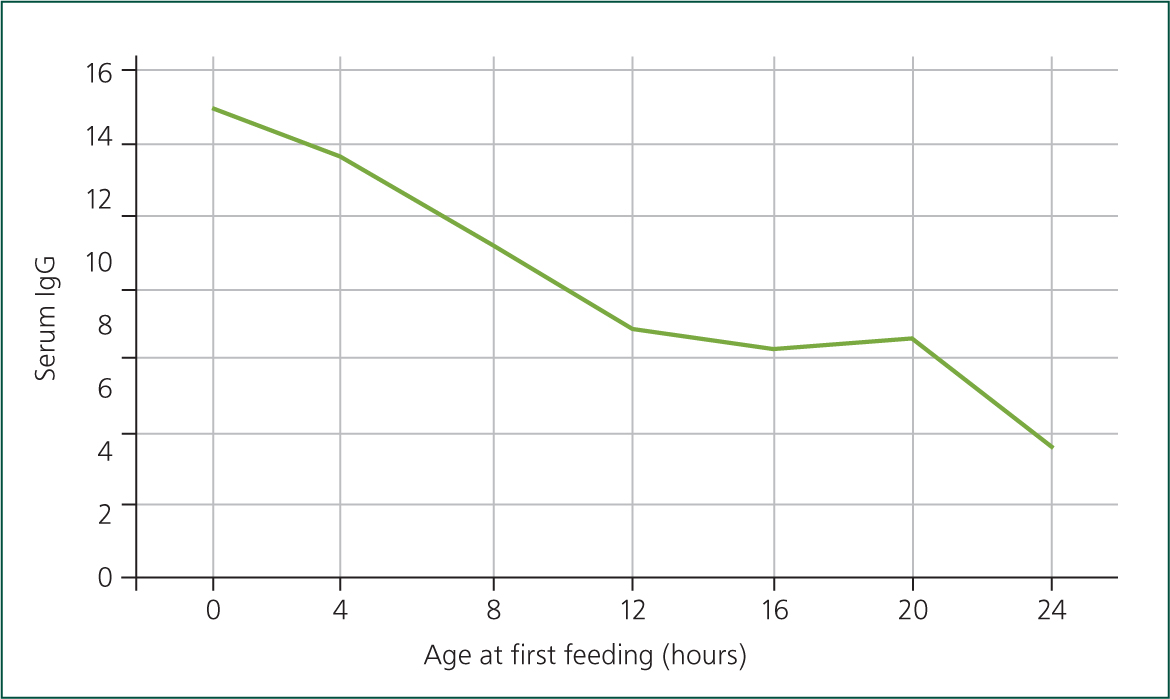

Quality of colostrum is affected by how soon it is harvested. Absorption by the calf is affected by how soon it is fed. In a process referred to as ‘closure’, the efficiency of immunoglobulin absorption through the gut lining of the calf decreases with time from birth to be completely closed at approximately 24 hours (Godden, 2008). When the calf is born cells lining the surface of its gut are able to absorb large molecules such as immunoglobulins whole. Absorbed immunoglobulins pass into the bloodstream and are immediately active and able to fight invading infections (Blowey, 1999). The cells lining the gut are rapidly shed so that by 24 hours none are left.

Despite the length of time to gut closure, immunoglobulin transfer across the gut is optimal in the first 4 hours after calving and there is a progressive decline after 6 hours. Calves fed colostrum more than 4 hours after birth are 2.7 times more likely to have FPT than those fed within 4 hours of birth (Beam et al, 2009). This is because fewer immunoglobulins are able to transfer into the gut. Figure 7 shows how calves fed later have lower immunoglobulin levels (Stott et al, 1979).

sQueaky clean

Colostrum is an important source of nutrients and immunoglobulins, but it also represents one of the earliest potential exposures of calves to infections (Godden, 2008). Bacteria in colostrum may bind free immunoglobulins in the gut or block uptake and transport of immunoglobulins into the cells lining the gut, thus reducing efficiency of immunoglobulin absorption (Morrill et al, 2012). In addition prior to ‘closure’ the gut is non-selective in its absorption and so direct uptake of bacteria may lead to septicaemia or diarrhoea.

Just as milk samples from cows can be assessed for bacterial levels, so can colostrum samples. Total bacterial count (TBC) should not exceed 100 000 colony forming units (cfu)/ml and faecal coliforms (TCC) should be below 10 000 cfu/ml (Lorenz et al, 2011). A nationwide evaluation of quality and composition of colostrum on dairy farms in the US found that almost 43% of colostrum samples collected had TBC >100 000 cfu/ml, and 16.9% of the samples had >1 million cfu/ml (Lorenz et al, 2011). A similar study in Scotland showed colostrum to be highly contaminated with mean TBC 4 570 000 cfu/ml, and mean coliform counts of 68 000 cfu/ml (Denholm and Haggarty, 2019). In northern Victoria, Australia, only 58% of colostrum samples met recommended industry standard for TBC and 94% for TCC (Phipps et al, 2016).

To keep colostrum sQueaky clean involves preventing colostral bacterial contamination plus minimising bacterial growth in stored colostrum. The cow should calve in a clean straw yard. The udder should be hygienically prepared before collection of colostrum. Clean technique and milking equipment which is clean and in good working order, are necessary to minimise bacterial contamination of colostrum (Corke, 2010). TBCs are low or nil in colostrum stripped directly from the udder. This emphasises the need to minimise contamination by milking into a clean sanitised bucket, keeping collected colostrum covered, and handling colostrum using clean, sanitised storage or feeding equipment (Godden, 2008).

Unless it is to be fed right away, colostrum should be frozen or refrigerated within 1 hour after collection (Godden, 2008). Colostrum stored in warmer conditions (i.e. 22°C) has >42 times more bacteria present and a pH 0.85 units lower, resulting in a serum IgG concentration two times lower than colostrum that is either pasteurised or untreated, but kept at 4°C for 2 days (Cummins et al, 2017).

Colostrum can be stored in a refrigerator for up to 2 days. If it is to be kept longer than this then it should be frozen or a preservative added. Only colostrum of good quality measured by a colostrometer or Brix refractometer should be frozen. It can then be stored for up to a year at -18 to -20°C, ideally in freezer bags which freeze flat, and so defrost quicker than milk cartons, and can therefore be used more quickly when required (Figure 8). It is a good idea to write cow I.D. and date of storage in permanent marker on the bag to allow older stored colostrum to be used first, but also if a cow is later identified as having Johne's disease the colostrum can be discarded.

Potassium sorbate at 0.5% together with refrigeration at 4°C can also decrease the bacterial load of colostrum. Potassium sorbate is a preservative (E202) widely used in human food and drink manufacture for its antibacterial and antifungal properties (Patel et al, 2014). Colostrum storage in a refrigerator can be extended to 4 days by adding potassium sorbate.

An additional tool gaining popularity in the UK for preserving colostrum is pasteurisation (Figure 9). 60°C (140°F) for 60 minutes to batch-pasteurise colostrum is sufficient to maintain immunoglobulin activity and colostrum fluid characteristics, while eliminating or significantly reducing important infections (Godden, 2008). These infections could include Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (Johne's disease), Mycobacterium bovis, E. coli, Salmonella species and Mycoplasma species, which have all been isolated from colostrum.

Pasteurised colostrum can be given to the calf directly or frozen for up to a year and fed at a later date. Pasteurised colostrum improves passive transfer versus fresh colostrum (Elizondo-Salazar and Heinrichs, 2009; Godden et al, 2012). There are fewer bacteria to bind with immunoglobulins to prevent them passing through the gut, and also fewer bacteria to block sites of absorption. This all leads to a better uptake of immunoglobulins by the gut with pasteurised colostrum. Pasteurisation of colostrum and milk has been shown to significantly decrease morbidity and mortality (5.2 and 2.8%) in comparison with calves receiving non-pasteurised colostrum and milk (15.0 and 6.5%), respectively, during the first 21 days of life, even in animals receiving appropriate colostrum ingestion (Armengol and Fraile, 2016).

Quantify

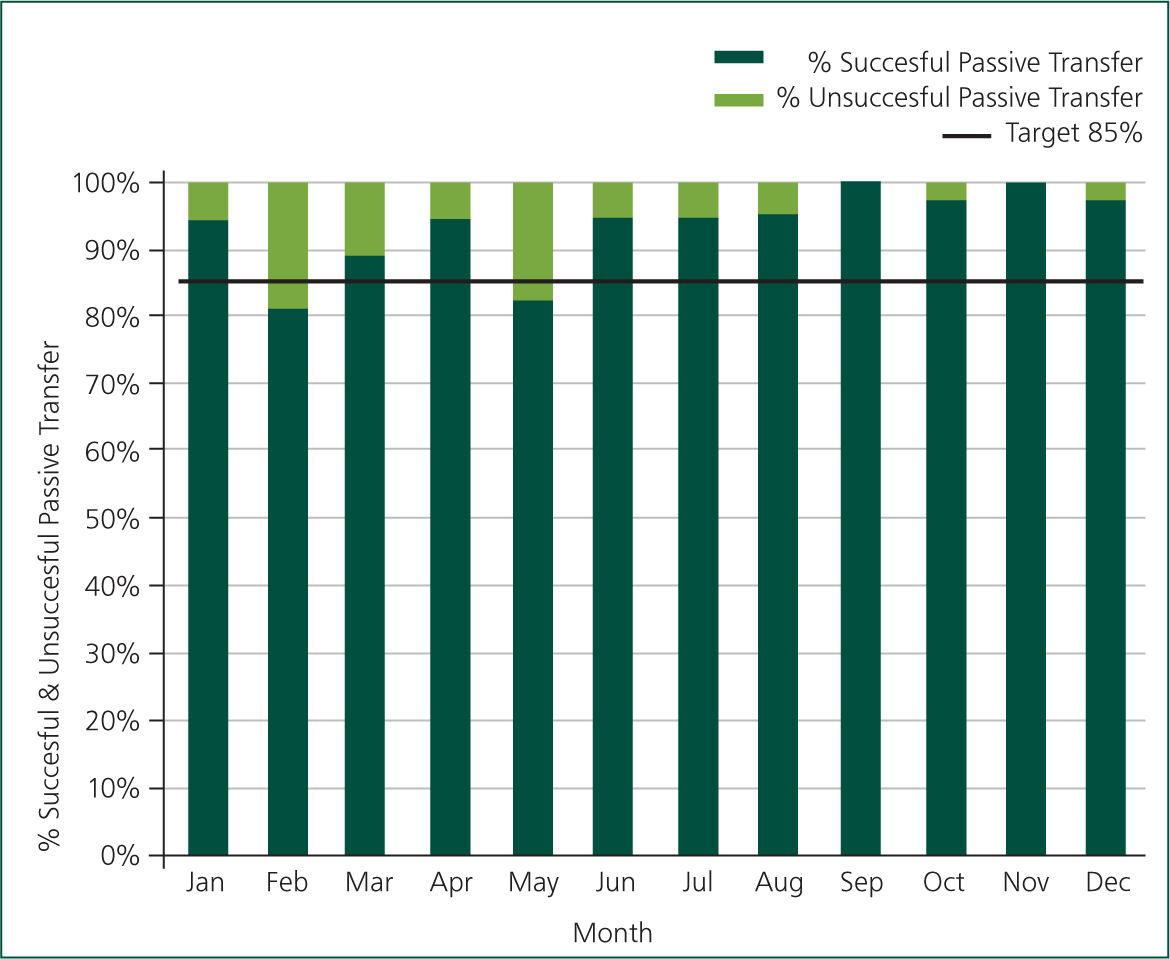

There is no point putting new colostrum management practices in place if progress cannot be monitored. Monitoring focuses on measuring passive transfer. The gold standard test for measuring IgG in serum is radial immunodiffusion (RID) which directly measures the IgG in a sample (Cuttance et al, 2017). RID may be cost prohibitive, and test results are not immediate, so more appropriate is an indirect test — serum total protein by refractometer — which is the most reliable test for herd screening in practice (Weaver et al, 2000). It is a simple, rapid and inexpensive tool. All farm veterinary practices should have the necessary equipment for this, however currently only 3% of veterinary surgeons routinely test calves for passive transfer (Atkinson, 2014).

A serum total protein concentration of 52 g/litre is equivalent to an IgG concentration of 10 g/litre. On a healthy, adequately hydrated calf, a serum total protein of 52 g/litre or greater is therefore associated with adequate transfer of passive immunity.

Regular monitoring of colostrum management by blood sampling calves enables longer-term patterns to be built up (Figure 10). A target of ≥85% of all calves sampled having a result of ≥52 g/litre is readily achievable. The odds of FPT are nearly 14 times higher on farms that do not routinely monitor total proteins to assess passive transfer compared with those that do (Beam et al, 2009).

Colostrum cleanliness — taking samples and performing TBCs and TCCs — can also be performed on a routine basis. Samples of colostrum can be taken at the point at which it enters the calf (the oesophageal feeder or nipple feeder), and placed into a sterile milk sample pot, refrigerated at 4–8°C before being submitted to a laboratory for analysis (Figure 11).

Conclusion

The feeding of an adequate volume of good quality, clean colostrum as soon as possible after birth is arguably the most significant effect a farmer can have on the life of a cow. Providing simple straightforward colostrum protocols of quality, quantity, quickly and squeaky clean will help. These are inexpensive to carry out, do not take significant amounts of time and are very effective at reducing morbidity and mortality. The ability to then develop programmes to routinely monitor colostrum management and measure success becomes hugely rewarding to all involved.

KEY POINTS

- Good colostrum management is the cornerstone of successful calf rearing.

- Calves receiving adequate colostrum have reduced risk for pre-weaning morbidity and mortality, with additional longterm benefits.

- Failure to receive adequate colostrum is known as failure of passive transfer (FPT) of maternal immunity.

- FPT is not a disease, but a condition that predisposes the newborn calf to the development of disease, and remains prevalent in the UK and other countries.

- When it comes to colostrum management the focus must be on five key areas: Quality, Quantity, Quickly, sQueaky clean and Quantify.

Calf disease: an immunological perspective

Endemic calf disease is significant in terms of economic loss, poor welfare and has impacts on medicine usage, international trade and climate change. Calf disease is multifactorial in origin and risk factors have been extensively discussed elsewhere. This article presents current understanding of the immune system of the calf and factors affecting its development. In early life, the innate immune system is a key partner with passive immunity acquired from the mother. The mucosal barrier and commensal flora synergise to protect from pathogens while adaptive immune responses are developing. Vaccination can be used as a tool to promote appropriate adaptive immunity. The development of the microbiota, innate and acquired immunity, and response to vaccination are all hampered by stress, immunosuppression and poor management. Improvements in calf health could be enhanced by appropriate understanding and management of the calf's developing immunity.

Endemic calf diseases are a well-recognised economic and welfare problem. Calf mortality represents a significant financial and genetic loss; particularly in the suckler herd, where production of one weaned calf per cow is the primary purpose, but also increasingly in the dairy herd, where calf sales supplement milk income and successful dairies seek to expand while remaining closed. Many dairy farmers are paying premiums for sexed semen and high quality genetics, the benefits of which are lost when calves die. Poor performance in calves that survive disease is still more costly, in reduced growth rates, fertility and milk production (Boulton et al, 2015). Added to this is the high labour demand and emotional impact on farmers of poor calf health and unprofitable businesses.

The most common endemic diseases, calf scour and bovine respiratory disease (BRD), in one survey affected 48% and 46% of UK dairy calves, respectively (Boulton et al, 2015). A study of suckler herds in Scotland found 3.2% of liveborn calves died between birth and weaning (Geraghty, 2019); while 12.4% of liveborn dairy heifers did not reach their first lactation in the survey by Wathes et al (2008).

A sick calf has poor welfare. Recently, media attention has been drawn to welfare concerns of livestock farming, dairy calf husbandry practices in particular, and a vocal animal welfare lobby carries strong influence with the general public. Farmers and veterinary surgeons must be able to visibly demonstrate excellence in calf rearing in order to respond to these concerns.

Calf diseases reduce the ability of UK agriculture to robustly function in the global marketplace, by increasing costs and reducing output. The presence of eradicable diseases, such as bovine viral diarrhoea virus (BVDV), reduces competitiveness in trade. In order to maintain and strengthen UK agriculture for the future, improving calf health must be a key target.

A current focus on our need to safeguard our environment and reduce the effects of climate change also has relevance here, since wastage of calves at any level results in unnecessary carbon emissions, both from the calf and its dam (Statham et al, 2017). Poor performance, with increased time to finishing or reduced milk yield, will have similar detrimental effects.

Concerns over the increase of antibiotic resistant strains of bacteria, and in particular the presence of multidrug resistant bacteria in humans, has led to many recent guidelines for the use of veterinary medicines in agriculture, followed by changes in prescribing practices (RUMA, 2019). Farmers are experiencing pressure from milk buyers or assurance schemes to reduce antibiotic usage where possible (Red Tractor, 2018). Calf diseases represent an important control point whereby prevention of disease can lead to reduced medicine use.

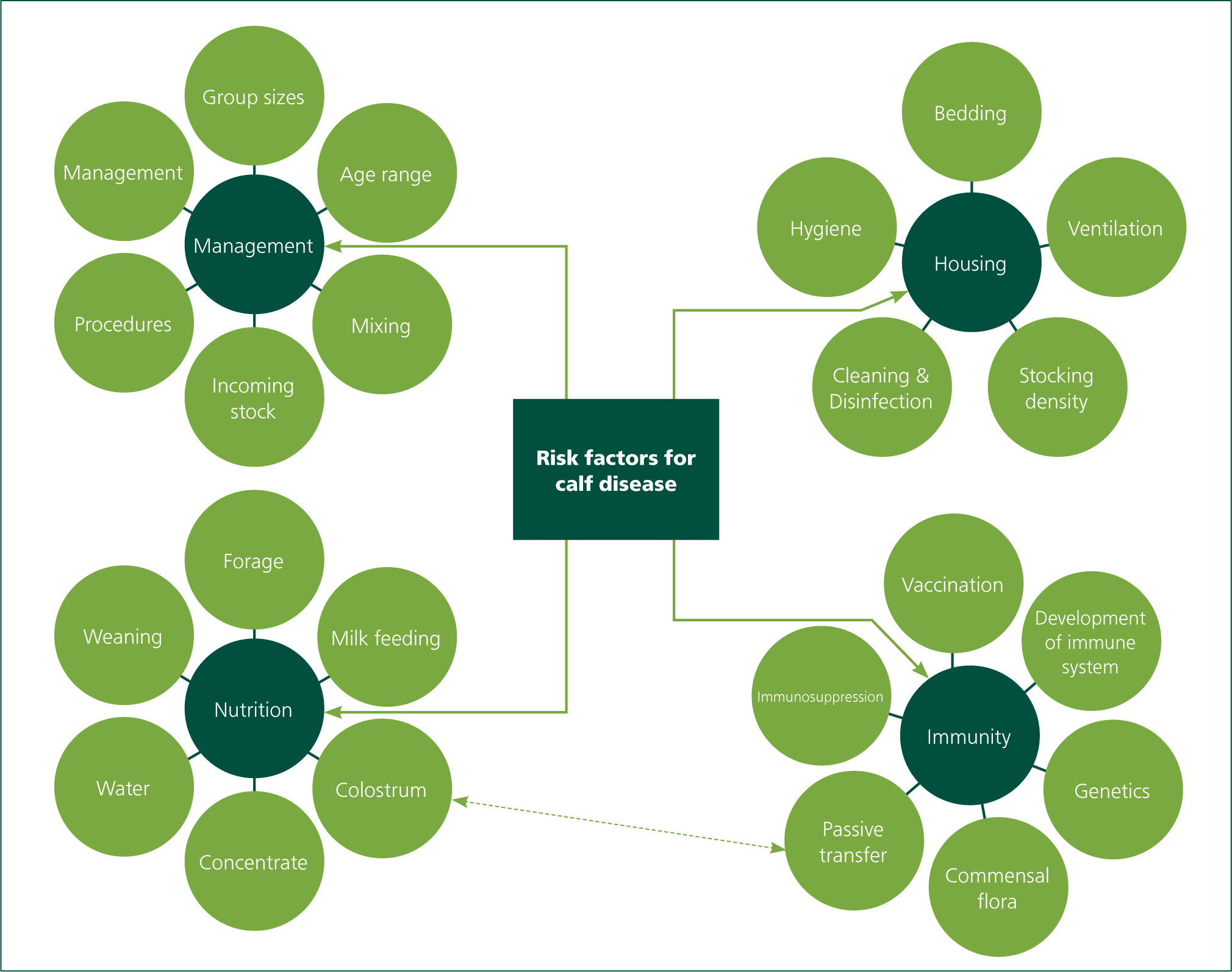

Risk factors in calf disease

Although specific pathogens are involved in most cases of calf disease, the pathogen load and occurrence of clinical signs is multifactorial in origin. Important risk factors are extensively discussed in veterinary literature and are summarised in Figure 1.

This article will focus on immunity in the pre-weaned calf in relation to endemic calf diseases. This important topic can help farmers and veterinary surgeons develop strategies to maximise the calf 's own ability to fight disease, by both enhancing the development of innate and adaptive immunity and the appropriate use of specific vaccines. These strategies are particularly important to the goal of reducing antimicrobial use on farm.

The immune system of the calf

Calves are born with innate immunity in the form of physical barriers such as skin and mucosa, which function in concert with commensals, and cells such as phagocytes and granulocytes, which are primed to respond to conserved pathogen identifiers or microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMP) via pathogenrecognition receptors (Hulbert and Moisá, 2016).

An innate immune response is stimulated by the hypothalamicpituitary axis, which responds to cytokines and MAMPs to produce glucocorticoids that stimulate inflammation. In calves with no development of adaptive immunity (less than 3 weeks old) this system is therefore crucial in responding to pathogen invasion. Acute stress improves immune stimulation; however chronic and/or multifactorial stress reduces resilience and immune function.

The adaptive immune system relies on specific pathogen recognition by T lymphocytes (cell-mediated immunity) and B lymphocytes (antibody-mediated immunity), which have been trained by previous exposure. In the calf, antibodies start to develop around 3 weeks of age (Hulbert and Moisá, 2016), but do not reach protective levels until weeks or months later. Of note are γδ T cells, which form a ‘bridge’ between the innate and adaptive immune system, since they are able to respond to a broad range of antigens. High circulating levels of γδ T cells are found in calves (Guerra-Maupome et al, 2019). Similarly, natural antibodies (Nabs) are present in the body before exposure to pathogens and provide a humoral innate response, activating complement and stimulating adaptive responses (Emam et al, 2019).

The period of delay in establishing calf antibody populations is covered by passive immunity from the dam via transfer of maternal antibodies into the circulation. No antibodies are transferred across the placenta, as in other species, but acquisition of maternal antibody is reliant solely on ingestion of colostrum in the first 24 hours of life and absorption of these antibodies across the gut wall and into the circulation. This topic is presented in a companion article in this supplement.

Maternal antibodies begin to decline around 2 to 3 weeks after birth but remain in the circulation for up to 8 months for BVDV and 10 months in the case of bovine herpesvirus-1 (Windeyer and Gamsjäger, 2019). There is huge variation in the amount of a specific antibody received by the calf, and it is difficult to predict the duration of individual protection in the field (Windeyer and Gamsjäger, 2019).

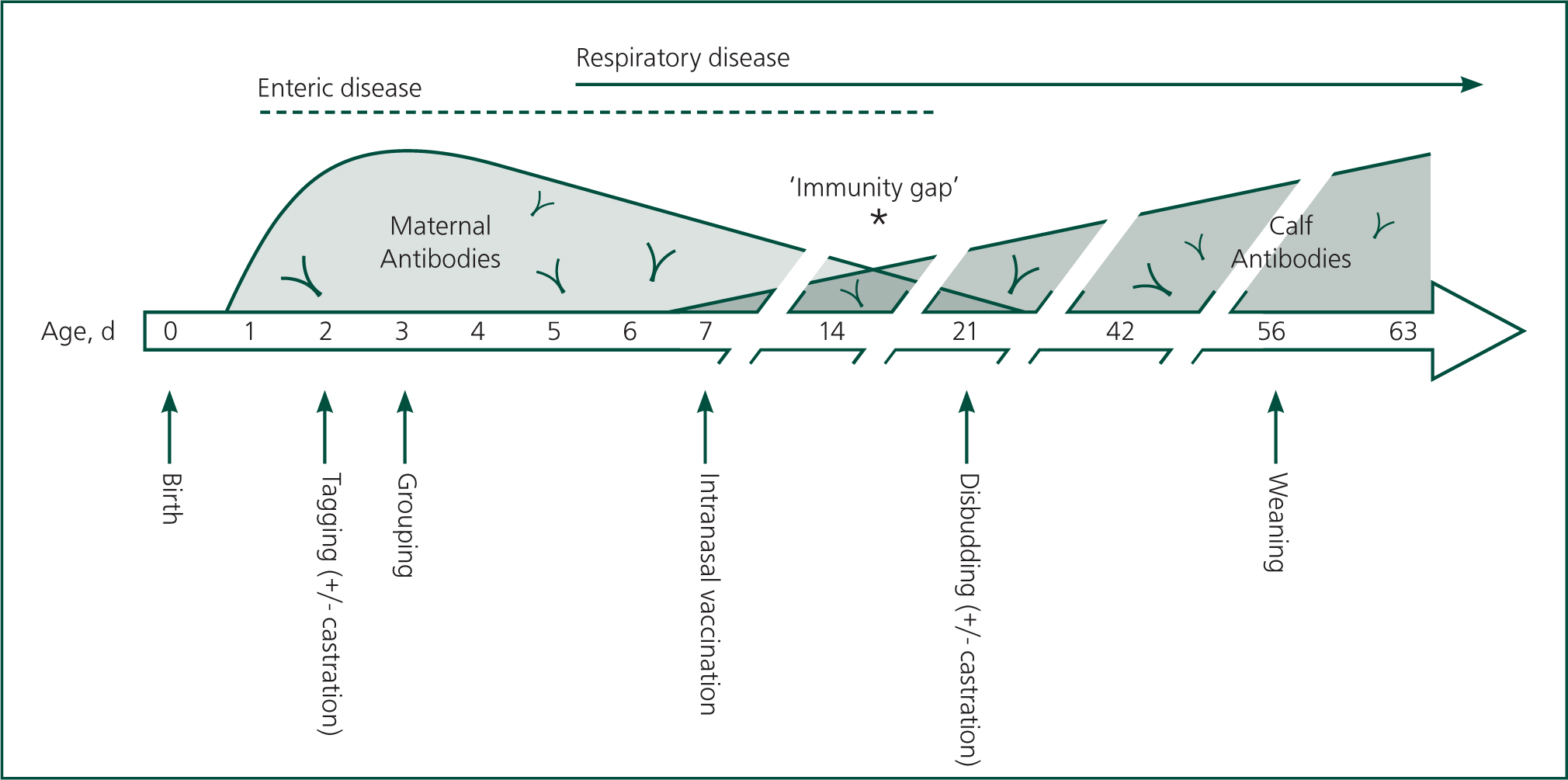

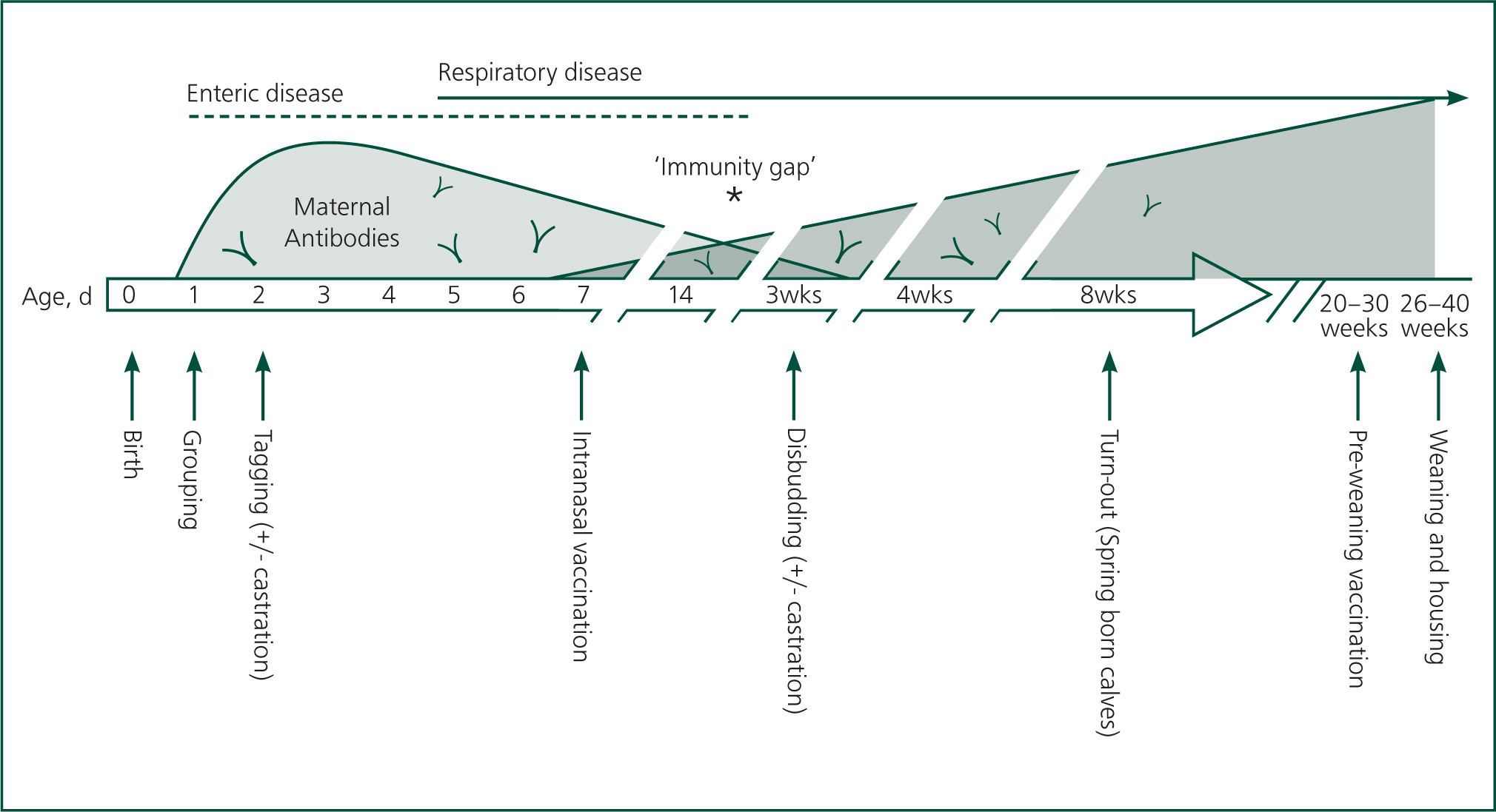

Calves ingesting adequate colostrum suffer from an ‘immunity gap’, when maternal antibody has declined to levels that are not protective, but the calf 's own antibodies are not sufficiently developed to protect against infection. The timing of this is variable with the specific disease and quantities of antibody ingested, but can be as early as 2–3 weeks. In a group of calves of similar age, it can lead to outbreaks of disease due to loss of herd immunity (Smith, 2019). It also represents an opportunity to try and enhance the calf 's immune system ahead of this window, by using vaccination. Figures 2 and 3 show ‘calf timelines’ for dairy and beef calves, respectively, with schematics of immune development and common timings of events.

Mucosal immunity

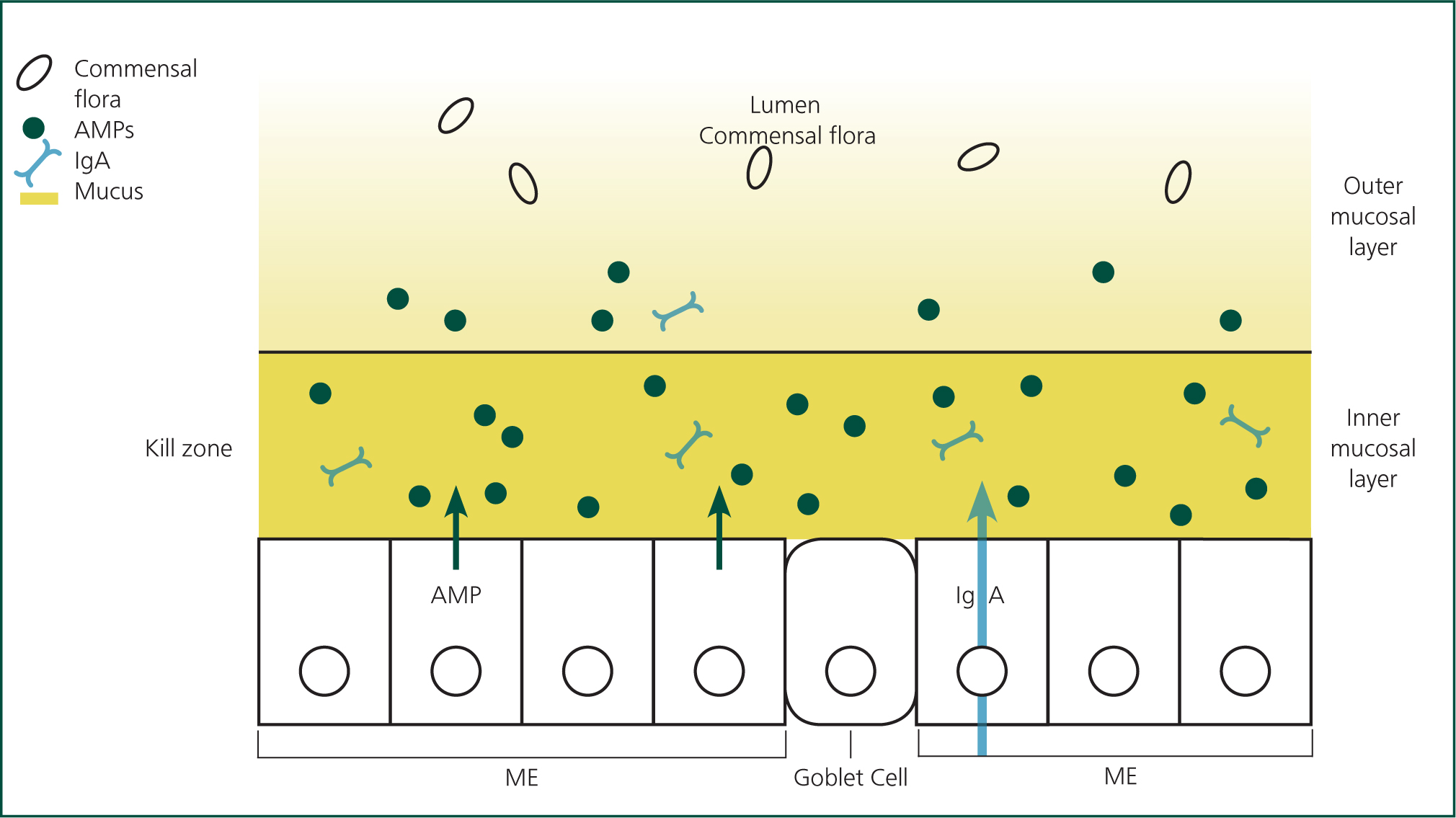

The mucosa (lining the gastrointestinal tract, respiratory, reproductive and mammary tissue) is the largest organ of the immune system and forms a protective barrier of mucus, antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and IgA, below which the epithelial cells act as a ‘firewall’. Development and maturation of these immune responses is dependent on the establishment of and interaction with the commensal flora (‘microbiota’) of the epithelium in the period aft er birth (Chase and Kaushik, 2019).

Mucosal epithelial cells are crucial in detection, stimulation, modification and maintenance of both innate and adaptive immunity. As first responders, they recognise MAMP and generate and regulate an appropriate immune response. They export IgA and secretory IgG as well as AMPs; these have a broad spectrum of action against bacteria, fungi and viruses by causing cell membrane disruption. Maintenance of tight junctions and establishing tolerance to both food antigens and commensal flora are other essential functions. Figure 4 summarises the functions of the mucosal barrier.

At birth, the intestinal epithelial cells are not linked by tight junctions and the gut is ‘leaky’. This permits the translocation of maternal antibody and leucocytes but must be closed as soon as practical to prevent the translocation of pathogens. Interaction with the microbiota, specifically Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium spp., upregulates the production of the relevant proteins to significantly tighten the junctions over the first 24 hours (Gomez et al, 2019). It is worth noting that dietary changes, specifically abrupt introduction of solid food, can result in increased leakiness and thus increase permeability and susceptibility to pathogens.

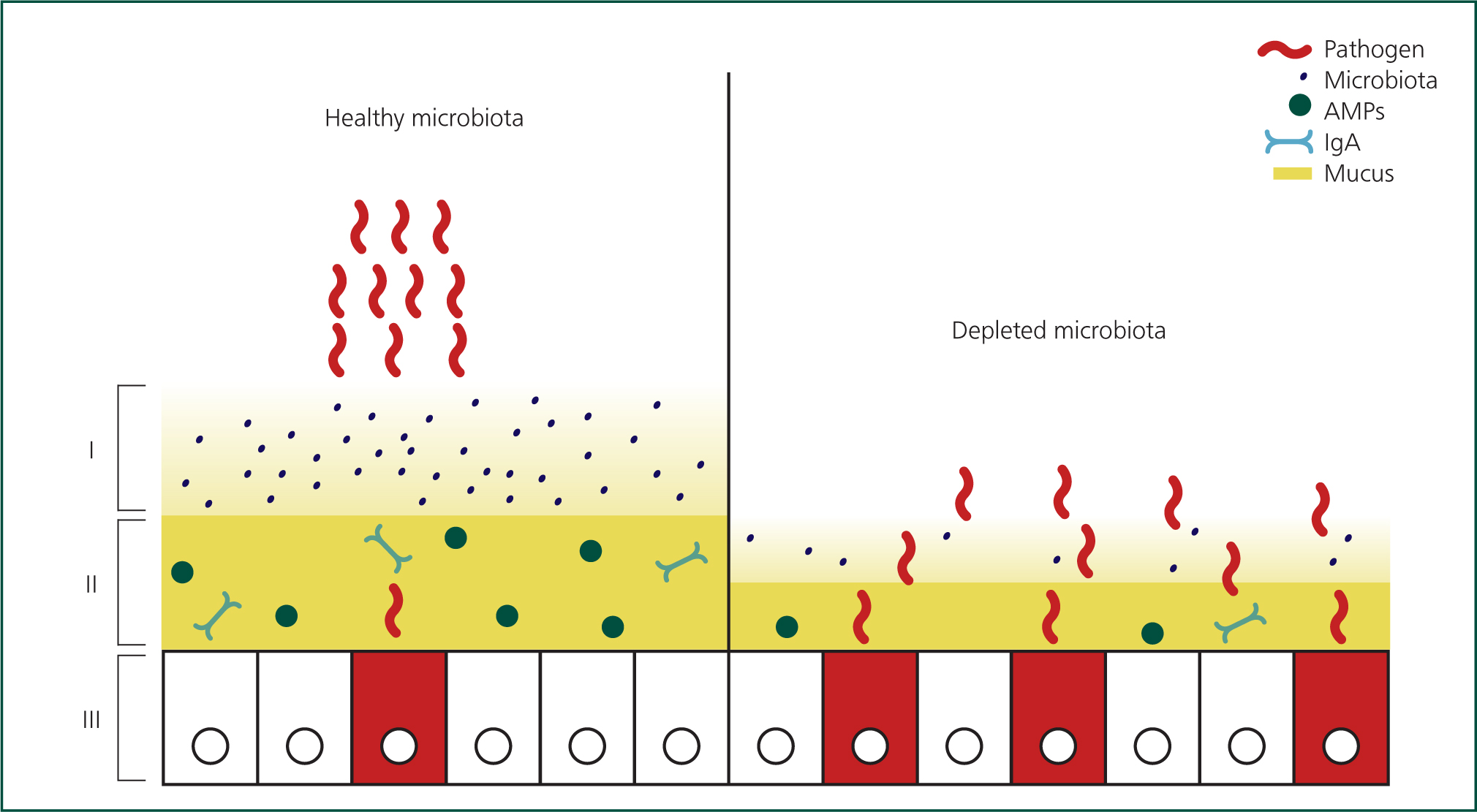

The microbiota has important protective functions at three levels, this is illustrated in Figure 5. First, within the gut, it competes with pathogens for space and nutrients. Second, within the mucus layer, it stimulates production of AMPs, IgA and mucus to enhance existing protection. Third, it matures and recruits T cells, granulocytes and phagocytes. In situations where the microbiota is reduced or absent (‘dysbiosis’), the calf has little or no resistance to invading pathogens (Chase and Kaushik, 2019). Dysbiosis is particularly associated with susceptibility to Johne's disease as well as other enteric pathogens (Chase, 2018). Factors influencing the microbiota are presented in Figure 6.

Microbiota are acquired first of all from the vaginal canal, and then oral and cutaneous organisms by licking and sucking. Colostrum ingestion is another important step in the initiation of the microbiota, which is initially composed of facultative anaerobes, then followed by strict aerobes. The flora undergoes instability and transition through the first 30 days of life (Gomez et al, 2019), during which time everything possible must be done to promote its richness and diversity. One logical conclusion is the use of probiotics, (containing live bacteria and/or yeasts) and prebiotics (oligosaccharides and fructans to encourage commensal growth) to promote the establishment of an anaerobic environment, while phytonutrients (e.g. oregano, garlic) and polyunsaturated fatty acids can help regulate immune responses (Ballou et al, 2019).

Dysbiosis is caused by many factors as described in Figure 6, but of particular relevance to this article are: stress, Caesarean section, nutrition and antibiotic usage.

Stress

Moving or mixing calves, disbudding and castration procedures all result in stressed calves and reduce the diversity and quality of the microbiota.

Caesarean section

It is proposed that birth by Caesarean section prevents access of the calf to the vaginal mucosa and so it is lacking in some crucial bacteria to establish its microbiota (Chase and Kaushik, 2019).

Nutrition

Abrupt diet changes also bring about changes in pH and severe population shift s within the microbiota. In pigs, low food and water intake is sufficient to cause dysbiosis and diarrhoea.

Antibiotic usage

Use of oral and parenteral antibiotics disrupts the homeostasis of the microbiota and promotes the overgrowth of pathogenic bacteria at the expense of beneficial bacteria. It takes weeks to months for the microbiota to return to a normal state (Chase, 2018). Farmers should be reminded that this is one of the dangers of feeding waste (antibiotic-containing) milk.

Preventing dysbiosis is particularly relevant to protecting calves from enteric disease.

Immunosuppression

Immunosuppression in calves seriously undermines their ability to fight disease. Common causes of immunosuppression in calves are: stress, nutrition, concurrent disease, BVDV, and Mycoplasma bovis.

Stress

A state of stress may be initiated in calves before they are even born. Dams stressed during pregnancy produce off spring that are less resilient and immunocompetent (Hulbert and Moisá, 2016), and so excellent dry cow management becomes crucial to calf health, not just for this reason.

Birth is a stressful process, particularly with dystocia. In itself this may reduce immune function and may be combined with reduced or delayed intake of colostrum. Stress in the calf under 1 week of age is coupled with a reduced ability to thermoregulate, increasing susceptibility to starvation and disease.

Movements and mixing are all early sources of stress; as are disbudding and castration, see Figures 2 and 3. Multiple procedures, e.g. castration and disbudding at the same time, have an additive inflammatory effect, which was attenuated by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) use. Calves pair housed from a young age showed less fear of novelty, improved concentrate intake and better transitions to weaning and larger groups, all suggesting reduced stress levels (Costa et al, 2016).

Poor environment, e.g. temperature extremes, unhygienic bedding, inadequate ventilation, causes calves to use excess energy combating these factors and compromises mucosal barriers, especially respiratory epithelium.

Nutrition

Calves require metabolic energy to fight pathogens, and yet many UK dairy calves are still fed only minimum milk quantities, barely enough for maintenance. AHDB Dairy recommend 15% bodyweight as a minimum daily requirement for calves — this equates to 6 litres a day for a 40 kg calf and 9 litres a day for a 60 kg calf. This is sometimes reduced further or omitted in farmer's treatment of calves with scour, despite clear advice to continue milk feeding diseased calves (Lorenz, 2013). Suckled calves have much more control over their milk intake, but if anorexic due to disease will require supplementary feeding, for which suckler farmers may have neither the equipment nor the experience.

Fresh water is essential for rumen development and should be supplied from birth, yet may be omitted or inaccessible (inadequate trough space or sited at adult height). Dehydration results in increased viscosity of mucosal secretions which can permit increased bacterial colonisation (Ackermann et al, 2010).

Abrupt changes in feed are likely to result in dysbiosis and immunosuppression due to stress (see above), therefore introduction of concentrate should be at birth and calves should be consuming at least 1kg/head/day before weaning to minimise stress and therefore disease post-weaning (Lorenz, 2013). This applies to suckled calves as well as dairy calves, although the timescales are different.

Concurrent disease

Early disease in the calf, especially septicaemia, is associated with reduced physiological and behavioural responses in subsequent disease. This increases susceptibility and reduces detection of disease.

Concurrent or sequential diseases, particularly scour and BRD, increase stress levels and place a heavy demand on the immune system which it may struggle to meet.

Many cases of bacterial BRD are caused by opportunistic nasopharyngeal commensals (Mannheimia haemolytica, Pasteurella multocida, Histophilus somni, M. bovis) that invade the lungs following periods of stress and/or primary viral infections (parainfluenza-3, respiratory syncytial virus, bovine herpesvirus-1, BVDV), which compromise mucosal defences, disrupt microbiota and cause immunosuppression (Ackermann et al, 2010; Workman et al, 2019). Synergy of M. bovis with other respiratory pathogens appears to occur and is a topic of current research (Maunsell and Chase, 2019).

BVDV

The presence of endemic BVDV or introduction of a persistently infected (PI) calf in a herd will result in acute BVDV infection in those calves not born PI. Besides inducing acute viral illness, BVDV causes immunosuppression and weakens the response to other pathogens. BVDV viraemia results in lymphopenia, apoptosis of peripheral lymphocytes and reduced phagocytic function of macrophages (Lanyon et al, 2014). Respiratory infections are exacerbated by concurrent BVDV infection.

Mycoplasma bovis

M. bovis is remarkably good at disrupting, evading and modulating the immune response, e.g. directly inhibiting respiratory epithelial cells, exhibiting surface antigen variation, forming biofilms, inducing cytokine secretion (Maunsell and Chase, 2019). It is rare for an effective immune response to develop which is able to clear M. bovis and in fact the optimal immune response remains unknown, although both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses are generated. The ineffective immune responses tend to contribute to the chronic inflammation that is often the result of infection, for example oxidative injury by macrophages causing caseonecrotic lesions.

Vaccination

Vaccination may be employed as a strategy to protect calves in the early phase where they are reliant on passive immunity, by vaccinating pregnant dams to stimulate colostral antibodies. This is commonly practiced in the UK with rotavirus, coronavirus, Escherichia coli and clostridial vaccines.

Early life vaccination may also be used to prime the calf 's adaptive immune system in preparation for the immunity gap or management events such as grouping or transport. Interference by maternal antibody is a challenge that must be overcome, and parenteral vaccination in this situation is unlikely to result in seroconversion. The exact mechanism of interference is still not understood (Windeyer and Gamsjäger, 2019). Calves with confirmed failure of passive transfer can be vaccinated parenterally and it is recommended to do so (Windeyer and Gamsjäger, 2019).

Intranasal vaccination with modified live vaccines can circumvent maternal antibody and produces short-lived (usually around 12 weeks) reduction of clinical signs and viral shedding when used in seropositive calves. There is also some evidence that it primes the immune system to better respond to subsequent vaccines (Windeyer and Gamsjäger, 2019).

Timing of vaccination is an important consideration, both with regard to the age and likely stress levels of the calf. Calves that are malnourished, immunosuppressed or already diseased will have a reduced or absent response to the vaccine and should not be vaccinated (Richeson et al, 2019). Completing vaccine programmes before weaning is beneficial for both the dairy and suckled calf since weaning represents a severe and chronic stress and is often accompanied by other events such as mixing. Vaccinating at a time of acute stress, e.g. tagging, disbudding, may in fact improve the immune response to the vaccination due to activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis.

Conclusion

A working knowledge of the immune system of the calf, and the essential role of good nutrition, vaccination and minimising stress, can help veterinary surgeons advise farmers on optimal husbandry, and reduce the economic, welfare and environmental impacts of calf disease.

KEY POINTS

- Developing the calf's own immune system to fight disease represents an important target for disease prevention.

- In the first weeks of life, a calf's immunity is reliant on passive immunity acquired from the dam and its own innate immune system.

- The innate immune system needs to develop after birth and this process is favoured by establishment of normal commensal flora, correct nutrition and avoidance of stress.

- Antibiotic use, immunosuppression, concurrent disease and chronic stress are all detrimental to immune system development.

- Vaccination can be used to prime the adaptive immune system and can ease the transition between reduction of circulating maternal antibodies and development of the calf's own adaptive immunity.

How to engage farmers in youngstock care: a clinical forum

The importance of youngstock care cannot be under estimated. Due to the financial impact in such tight economic times, efficiency of the future herd is of increasing importance. Farmers are under the spotlight to ensure welfare is optimised which will become increasingly difficult due to the obligation to rear all calves. Rearing healthy happy calves is no easy job but can bring pride and job satisfaction to a team that is doing this well. However when things are going wrong in the calf shed the negative effects are acutely felt, with a drop in calf welfare and the financial drain this creates leaving a demoralised team. It is essential that all clients see optimising calf health as a way of being successful and not something that can be corrected once the animals grow.

There is a great amount of room for improvement on most farms in youngstock care, whether they be beef or dairy. Beef suckler herds should be focused on this area as this is where the profit is made; the number and weight of calves weaned compared with the number of cows put to the bull as a key profit indicator. AHBD beef and lamb, stocktake 2016 figures state that the average non-severely disadvantaged suckler herd manages to achieve 85 calves weaned/100 cows put to bull (ADHB, 2016), however the target is 95. It is important to find out at which stage calves are being lost: is it poor conception rates? high abortion levels or still births? Problems at calving or pre-weaning?.

On dairy farms that use sexed semen all calves are seen as valuable, but with the number of beef x dairy rearers and growers, increasingly calves are now seen as a commodity worth investing in. Rearing systems are focused on fast growth rates and if the stock they buy-in are sub-standard then a farmer can soon lose his buyer.

Working with youngstock farmers can be difficult as traditionally they have always seen the veterinary surgeon as a cost. The future of veterinary surgeons is that we are giving more consultancy advice which has to encompass the whole herd. Working together is the key to effective youngstock care, alongside good record keeping on the farmer's side.

Communication is key to getting farmers to engage as well as for maintaining a working relationship as you find solutions together

Many farmers will now know the importance of calf care as it has been highlighted well in the farming press for the past 10 years. Ensuring that you approach it with a farm and farmer-specific twist in the author's exerience works well.

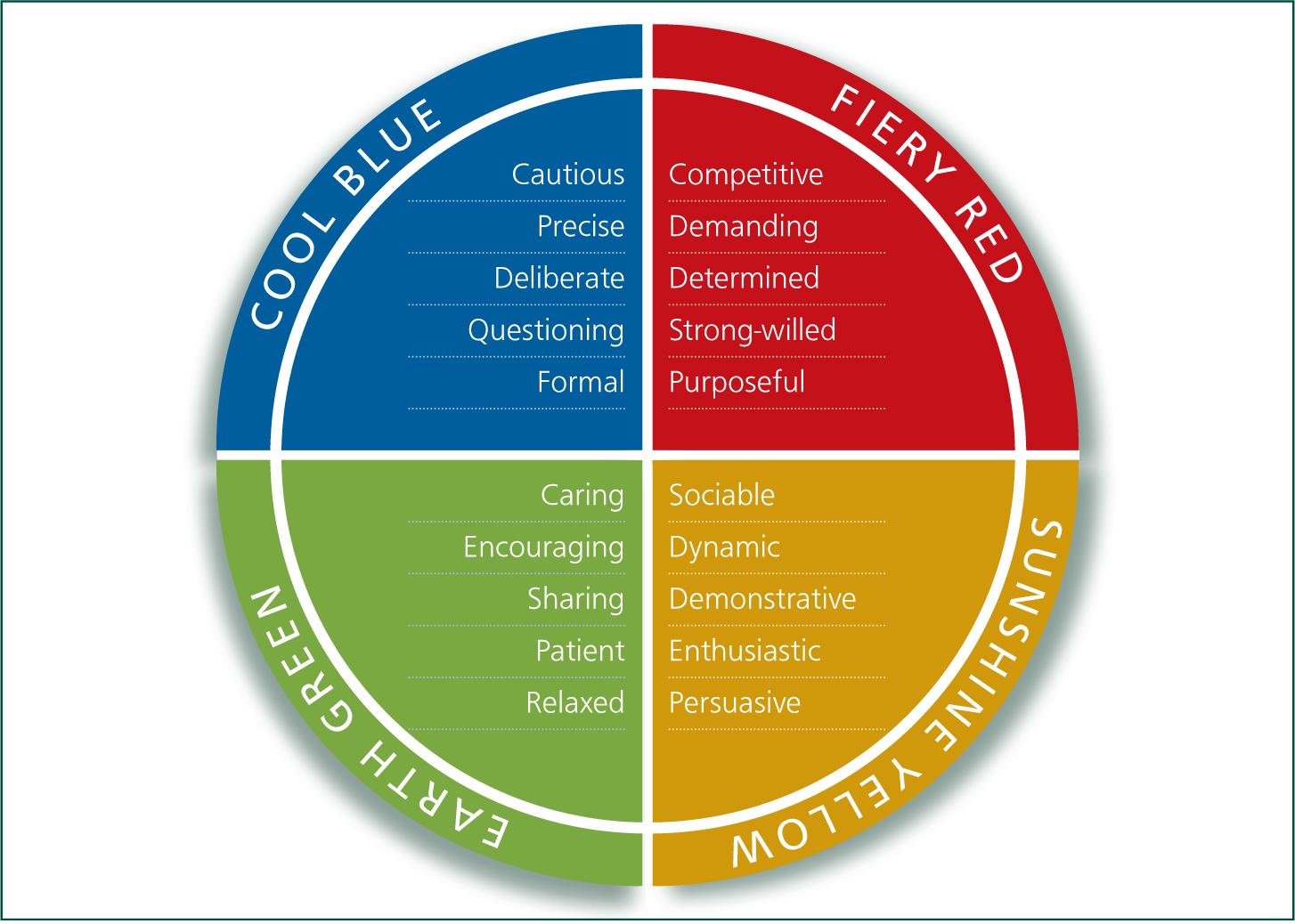

Know your personality type and be prepared for the farmer's

When communicating with anyone it is useful to be aware of your personality type as well as theirs (Figure 1). Communication with farmers is no different, and an awareness of personality types can really aid preparation and efficiency of vet-farmer meetings. If you are the lead vet on these farms you will already know the farmer and set-up well, however if there is not already an established relationship it is always worth speaking to the vet that knows the farm best prior to the meeting in order to gain an understanding of which personality type the farmer is. An understanding of the farmer type is in many ways as important as discussing what the lead vet believes to be the key problem, as making assumptions/carrying personal bias onto the farm can cloud your view, affect communication, and what you have identified as the issue may well be different to what the farmer wants to focus on in that meeting. For example:

- A Cool Blue farmer is likely to benefit from graphs and data and a lot of discussion time, however will be unlikely to commit to a change on that first meeting

- A Fiery Red will make a quick decision and want a quick bullet point style approach, but be prepared for confrontation and always remember the rest of the team

- An Earth Green will oft en be more focused on how these changes will affect the team, and be more open to discussion rather than bullet points, be careful not to come across as confrontational

- Sunshine yellow will also be more focused on the team, and be very enthusiastic however try to pin them down to achievable goals as they will want to say yes to everything.

Th is might sound rather simplistic, but it can be really useful to hold in the back of your mind and can help with managing expectations. For example, if you are a ‘Red Type’ personality you would expect everyone to make a decision and agree on it within the first meeting. If, however, the client is a ‘Blue Type’ personality such decisions are unlikely to be made so quickly and you would see the meeting as a failure. Equally, if you prepare with lots of graphs and data for a meeting with a ‘Green Type’ personality, the meeting may seem less rewarding than if you were discussing the problem with the ‘Blue Type’ personality who will love this formal, precise and, maybe, cautious approach.

Obviously we are all individuals and this should be kept in mind. Each meeting should be approached with the individual at the core, taking cues from their reactions, questions and responses.

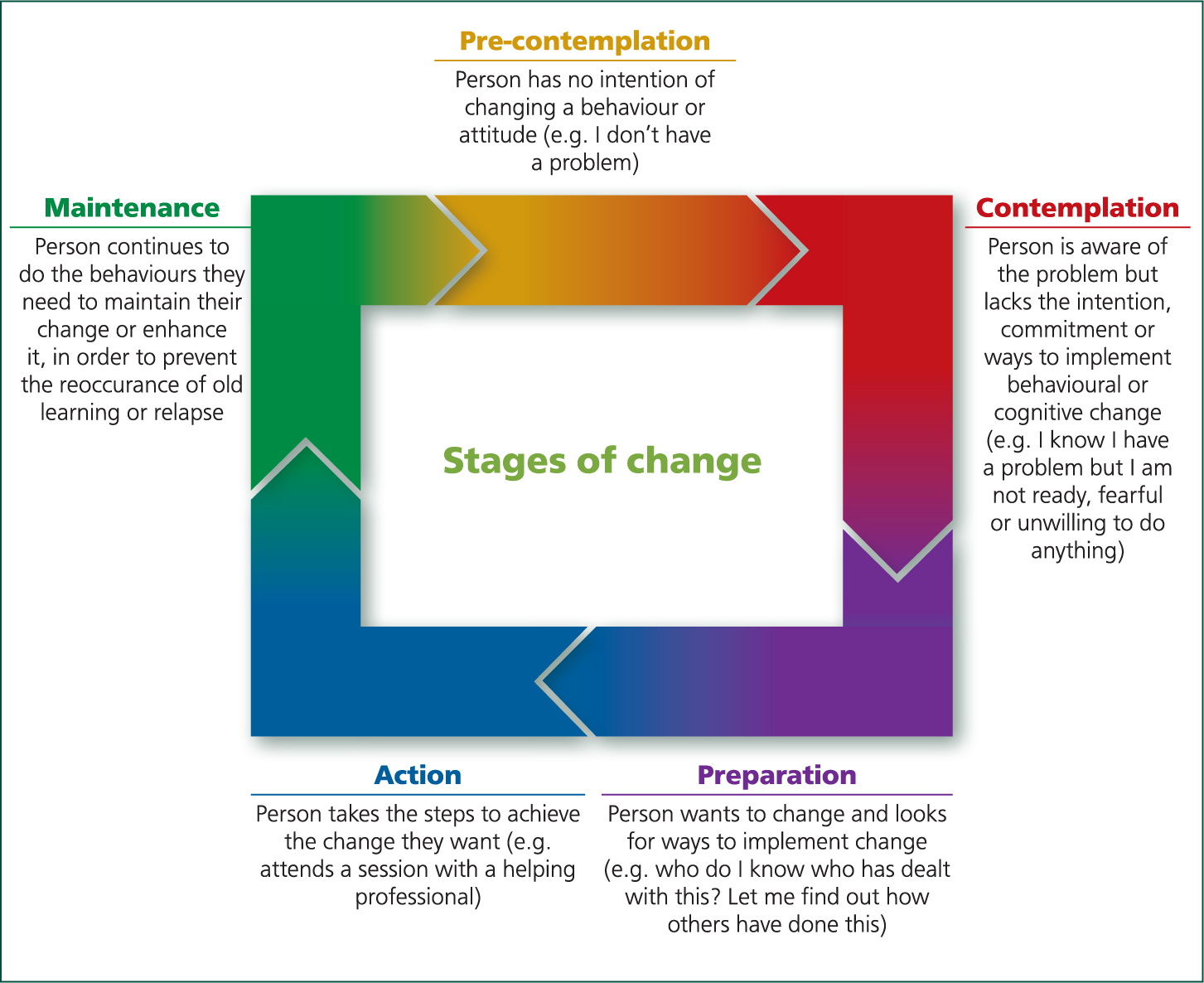

Change is difficult for everyone

Getting farmers to change can be hard and maintaining change within a team can be even harder, but do not be put off, it is achievable (Figure 2). Remember there are always the ‘first adopter’ types of farmer, the ones that are always willing to give new things a try and be innovators. Then there are the majority that can be divided into early and late adopters, before the laggards at the end. So, for success in achieving change start with farmers that are open to change and those that are early adopters, as trying to establish change on a laggards farm will be more of a challenge! Hopefully, this ‘first adopter’ will spread the word and allow your methods to trickle down throughout your client base.

In order for the farmer to make change he/she needs to want to make a change — where youngstock are concerned it is important that farmers realise that improvements made at this stage will be of benefit. The stages of change can be broken down into:

- Pre-contemplation — there is no intention of changing and the farmer is unaware of the problem

- Contemplation — the person becomes aware of the problem but lacks the commitment to make the change

- Preparation — the farmer desires the change and starts to looks for ways to implement it, this is the key stage to get involved in

- Action — this stage has been traditionally where the vet role has been, but to get more farmers involved we need to focus on the stages before as well.

- Finally the maintenance stage (Figure 2).

All stages require regular and constructive communication with the client if they are to understand the problem, what can be done about it, and to maintain the changes (Beedell and Rehman, 2000). There has to be an achievable end goal with tangible benefits to the client.

Knowing that you cannot expect a person in the pre-contemplation stage to commit to an action straight away is again important for realistic expectations. However, it is important that farmers at this stage are encouraged to come to meetings so they can move to the contemplation stage. Although, one to one meetings are oft en more constructive if you want a client to be honest with you.

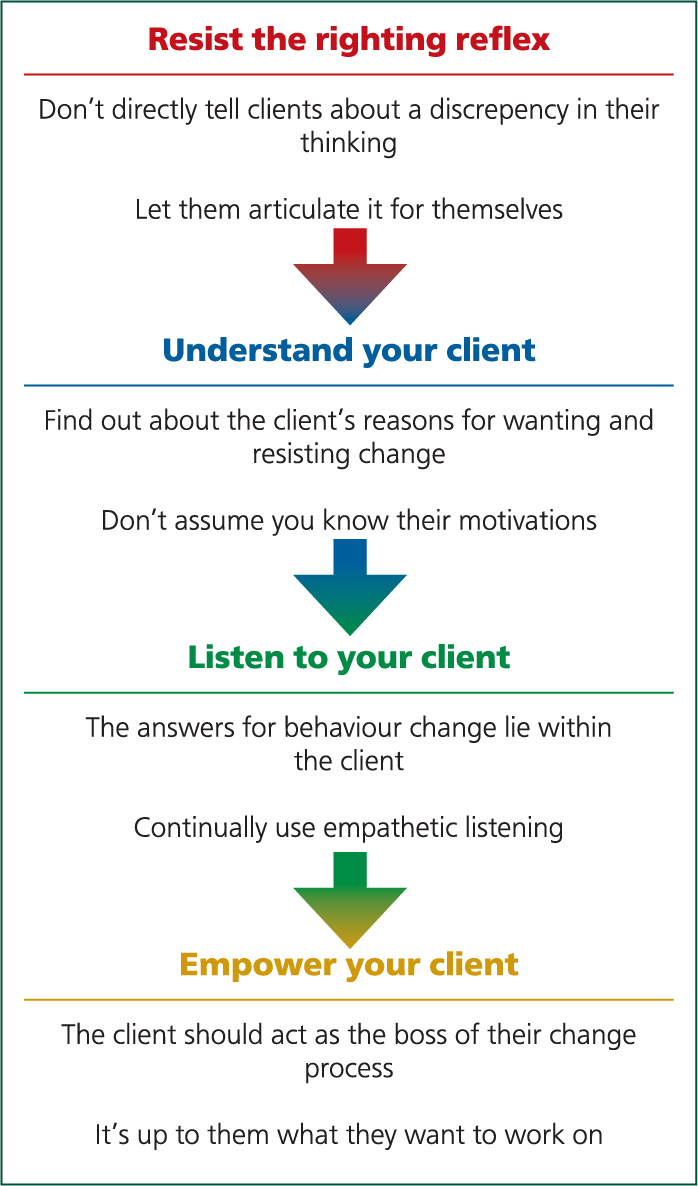

How to motivate that change

Motivational interviewing has recently been encouraged as a way to try to motivate farmers to make change particularly with regards to herd health. This can be further extended to youngstock care. One of the key principles is the ability to resist the righting reflex. The righting reflex is a natural response to try to make things better and give lots of suggestions yourself — however, this oft en has a ‘kick back’ effect, with the farmer listing reasons why the suggested changes cannot work or will not be possible. Traditionally as a veterinary surgeon in the consultancy role we see ourselves as needing to go to the farm with a list of solutions for the farmer. As a result we are naturally trying to tell them what to do. Letting them come up with the options of how to cure the problem themselves is key to them owning it and believing change is possible.

The other principles involved with making change on farm is an understanding of your client; this is a strong point for vets who are often working with a dairy farmer that they see every fortnight for a session anyway! However, remembering to listen to them and not to try to make your views fit can be difficult for some. Lastly the key is to try to empower the farmers and make them believe you can both do it together (Figure 3).

The author's approach to youngstock

Selecting farmers

Generally it is a good idea to invite all the farmers to meetings, so no one feels left out – rembering that oft en the first adopters will be more open to meetings compared with the laggard farmers. However, selecting a key 5-10 that you really think will benefit is key. Also including a few clients that are already on board with what you want to discuss, and that have already achieved the desired effect, is key as farmers are more likely to listen and believe other farmers than vets, and making change is more achievable if another farmer is actually already doing it that way. Whether the meeting is based on a farm and includes a farm walk or at a pub in the evening will vary depending in the group of farmers you want to attract, but having the key people there is important to create positive discussion, rather than you telling them what to do for an hour or so (Summer et al, 2018).

Preparation is key

When preparing data or knowledge try to remember the farmer's personality type and prepare according to what they will find most useful, i.e. more graphs, or more short bullet point approach, average age of first calving (AFC) is key as there is a lot of recent work on the economics of youngstock that can be discussed if this is a motivation for the farmer. Data on still births and deaths to weaning are also useful. Sales data of pneumonia antibiotics or scour rehydration products can be useful to again highlight the problem if reliable. It may also be useful to determine the colostrum protocol, i.e. is colostrum used from all cows? Is it tested before giving?

Over time a youngstock equipment box has been created in our practice. This contains some simple but really useful kit such as a lazer measure, smoke bombs, and blood tubes, but also includes more techniqual equipment such as a hot wire anemometer, ammonia meter and humidity monitor – these are not essential but can add to a discussion if based on housing changes.

What to be aware of

Th ere are some things to beware of, for example, some farmers will say the right thing, but you well know that what they are saying is not being achieved on farm — this, in the author's experience, is common when asking people about their colostrum protocol. For example the farmer promising that all calves are tubed within 4 hours, while the team is saying nobody is routinely on farm between 9 pm and 5 am, so making that not possible. Trying not to make the conversation confrontational can oft en be difficult; basing the conversation on facts such as recent total protein (TP) results can be helpful. Getting the whole team involved is key as often what the manager believes is happening on the farm might not be the case on the ground, and trying to establish this can be difficult.

Maintaining change

Maintaining change can be challenging. The good part about youngstock is that you can see change very quickly so within 2 weeks you can normally see a great improvement. Within 8-10 weeks a total change of pre-weaned calves have come through the system, so very different from, for example, cow fertility. Keeping contact with the farm is key during this time whether that be every other day sending a quick text to see if any calves are sick and whether they want to discuss the new treatment protocols, or whether a more empowering communication is required, such as finding out if there have been ‘any calves over night?’ or determining ‘how did the tubing colostrum go?’. The level and type of continued communication will vary depending on the farmer's personality type, however staying in close contact is key to achieving good results.

Once a good habit is formed and all is going well then you can step back and assess the continuing change, and then focus on the next area of youngstock care, while continuing to carry out periodic assessments. From the author's experience, it is easy to leave the farm feeling positive, write up some great notes from the meeting and think it is done — in these instances the farmer may then try the change for a few days, but as they are so busy as soon as a small hiccup occurs they revert back to old habits; however with your support these can easily be overcome allowing the farmer to move forward.

A case where the author has seen the greatest impact

Case study — calf mortality

Problem: Calf mortality was highlighted during an annual review on a herd milking 180 organic Friesian cows (52% Jan-March, 34% April-June, 47% July-Oct). In November there was a change of herdsman and many protocols were being reviewed. The farm had had little input from the vet, however when the new herdman started the owner wanted a review of all protocols including youngstock.

Action: A full review of all calf systems and husbandry was carried out and this highlighted pre weaning mortality and morbidity to be the main problem, however few reliable records were kept. Post-mortem examination of three calves were carried out, scour testing as well as pneumonia bloods were taken together with an in-depth assessment of medicines purchased. They all revealed that both scour (mainly Cryptosporidium parvum) and pneumonia were a problem. Bloods were taken from calves 2–8 days old and tested for total proteins to indicate colostrum management. These results were good which was a surprise as the current protocol was to leave calves with dams for days, without any extra management. This focused us on disease prevention and hygiene through good protocols, nutrition, as well as training staff to identify and treat sick animals.

As the herdman was new, we had very little to go on with respect to what his personality type, however when he had got the job he had emailed and asked for any previous reports and had sent the lead vet email questions which indictated he had spent time looking through records and inter-herd. This suggested he was a ‘cool blue type’ so we prepared in depth so that he could have all the information. However, we tried to be open minded as if we had got the personality type wrong then he might not take much notice of this work.

The data were made into graphs to demonstrate and the herdsman really got involved in data collection which was great to see.

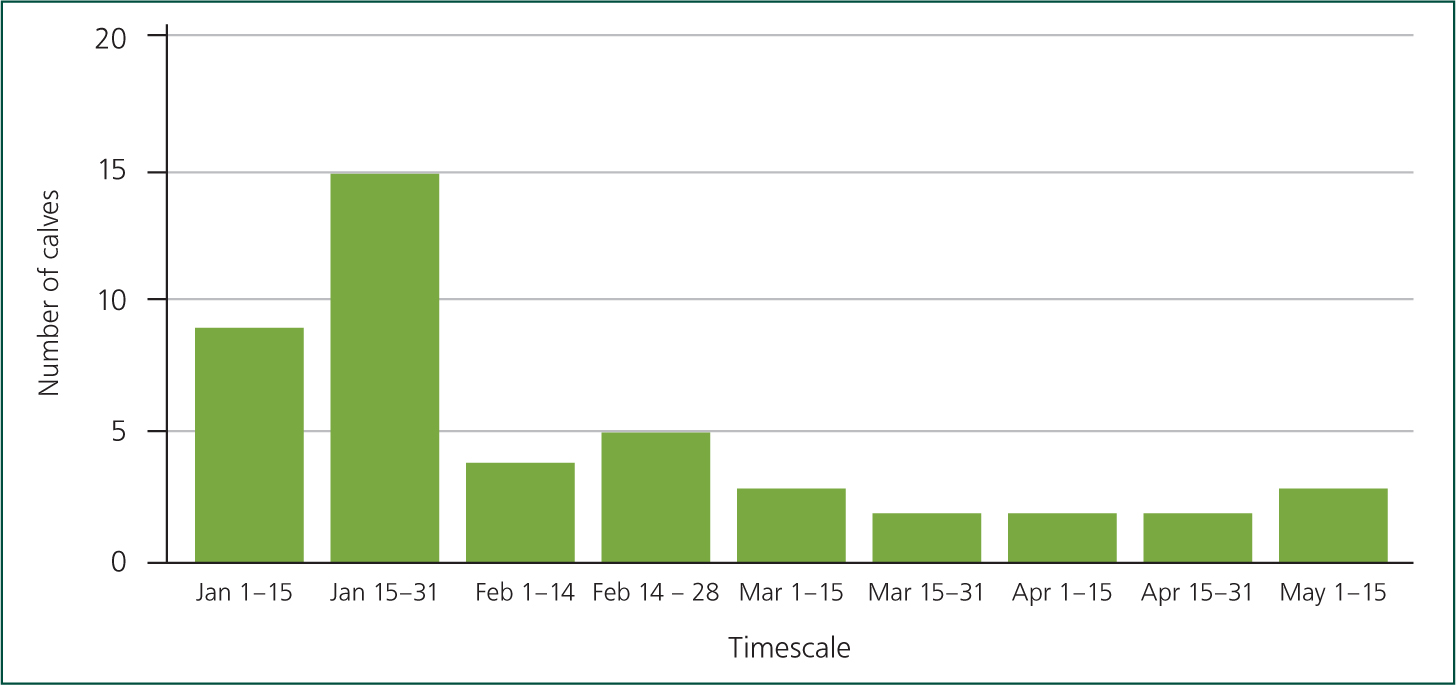

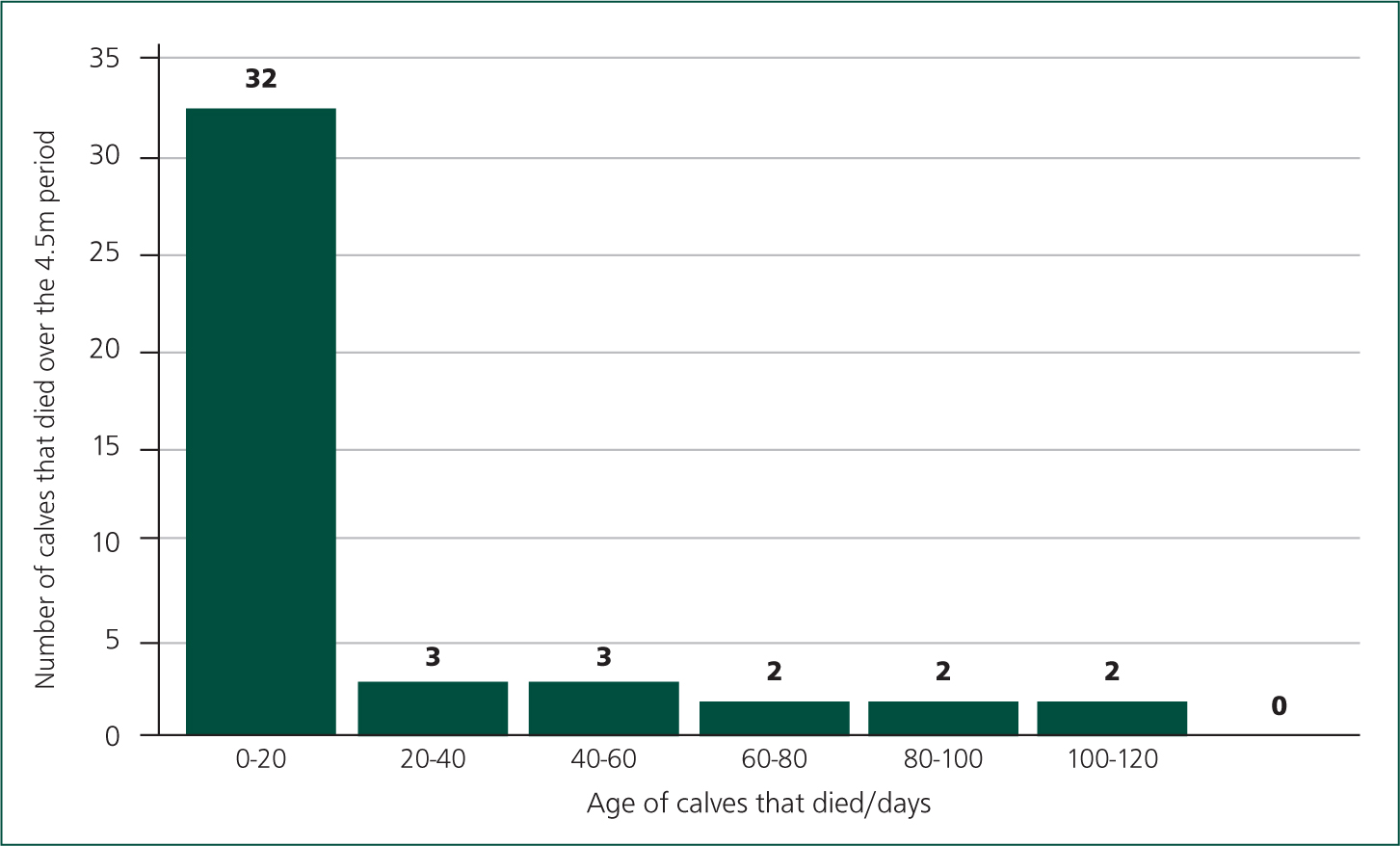

Result: I became involved during September 2014; by December 2014 the staff had settled into using the new protocols I suggested (vaccinations, treatments and disinfection protocols) and results were starting to be seen (Figure 4). During this time I visited the farm every fortnight purely to focus on youngstock, to make the staff comfortable with tubing calves, to ensure they understood the vaccination timings and the importance of thorough cleaning of milk equipment and housing between groups.

Figure 4 shows a sharp decrease in deaths from February onwards, which would have been the time when all calves on milk would have received all preventative vaccinations and medications and would have entered the shed after a thorough clean. I am pleased that this low level has been sustained and is now running at 6.2% (April data).

Figure 5 shows that the vast majority of deaths (31/42, 74%) had occurred between 0–20 days, which is to be expected with such a heavy load of scour contamination in the environment, and colostrum management relying on the calf to suck the cow. This also shows that record keeping had massively improved allowing more in-depth assessment of what was happening on farm. We are now addressing colostrum management as disease protocols are now controlled and I am visiting the farm monthly for youngstock visits.

How do you select the farmers and what do you do with them?

Fiona MacGillivray replies:

As mentioned earlier in this article, farmers have a number of different ways to obtain information about calf care; published articles, word of mouth (speaking to peers), vet practice farmer meetings, levy board knowledge exchange materials and meetings, to name a few. Jansen et al (2010) concluded that ‘there are different types of farmers that need to be approached in different ways using different channels’. Therefore, in my opinion, vet practices should be part of this mix, providing information and knowledge exchange through newsletters, farmer group meetings and by having a presence on social media so they can be seen as leaders and experts in matters relevant to their farmers. This helps to build a strong community where topics important to both vets and farmers can be raised and discussed.

Selecting farmers as advocates or supporters of an initiative, e.g. vaccination/colostrum management, then working together to share successes and challenges, can help others in the client base to better understand the application and practical implications of calf care practices. I'm not sure there's a ‘type’ of farmer to work with here. In my experience, some farmers who you initially feel are ‘difficult’ to work with can become your strongest allies when trying to share reasons for making some changes on farm that may be beneficial to others.

Jolanda Jansen replies:

There are various ways of segmenting farmers. You can select according to farm characteristics, such as size, practice revenue, animal health status, or on farmer characteristics, such as perceived willingness to change, age, education level. That all depends on your practice and personal goals. To start, be easy on yourself. Select the farmers with the most potential for success to gain confidence in your approach. For example, select farmers that you expect to be in business for the next coming 20 years and who have a need for a future-proof farm. From that group, select farmers that have no optimal youngstock health yet and who have lots to gain by changing their management. From that group select farmers who, in general, seem to like you and your practice.

Start with a maximum of three farms. You are a busy person, so be realistic in the services you can offer. Next time you visit that farm ask the farmer open-ended questions and listen before you respond! Your only goal of that moment is to understand what the farmer wants to achieve, so you can frame your future advice in the right way. Try to finish that converstation with booking a new appointment instead of trying to solve the issues that arise at that specific moment. Examples of open ended questions are ‘Just out of curiosity, for coming year/5 years what are your goals? What about your goals for youngstock? What could you do to reach your goals? How can I help you with that? Would you like to make a new appointment where we can further discuss this in-depth and help you achieve your farming goals?’

A ‘No’ is also an answer, and that's ok, don't take it personally. Then try the next farmer. Bottom line: ask questions, do not assume. There is a famous quote, ‘if you assume, you make an ASS of U and ME’.

Katie Fitzgerald replies:

Finding an opportunity to engage with your clients on calf health can be challenging and there is no ‘one size fits all’ route to engagement. Understanding the different personalities and goals of your clients is key in ensuring you find the right route in to engaging without creating barriers or finding yourself frustrated that your efforts are not resulting any meaningful changes.

For some farms the opportunity to engage may arise through a ‘problem solving’ scenario off the back of a direct calf health issue, whether this is an acute disease outbreak or high morbidity or mortality identified through performance monitoring. In these cases I find the key is timeliness — if things return to ‘normal’ the opportunity may be lost so getting stuck in while calf health is in the fore is important.

Other farms may respond to a more ‘outcome-based approach’. The opportunity to open the door to more proactive calf health advice may arise if they find they are failing to achieve targets such as age at first calving, a KPI that has been the focus of many youngstock initiatives. There is a wealth of evidence that early life performance has significant influence over productivity in the milking herd hence ‘Starting with the end in mind’ can allow you to focus your client's mind-set on improving calf performance as a platform to achieve their future heifer performance.

Many farms will already work with you closely in other areas of animal health and may be keen to engage in a more proactive calf health approach to match their monitoring of other areas across the farm. Discussion group meetings can be a useful starting point to share ideas used on other farms or commence new initiatives.

The starting point in the process for me is always in establishing a baseline in performance and setting targets that the team hope to achieve. It is also key to understand the processes that are currently in place. This often involves speaking to several members of the team as the assumed protocol is not always what is happening! Both these things are crucial in order to establish where bottlenecks are within the system and allow you to prioritise changes to have the biggest impact.

Ginny Sherwin replies:

As discussed previously, it is important to be inclusive of all farmers involved with calf rearing, including beef and dairy farmers. It may be necessary to use different methods of communication with different subsets of farmers for different situations and try to avoid the ‘one size fits all’ idea. I also think it is important to try and understand what motivates a farmer, whether it is producing the highest welfare stock, economics, complying with contract requirements or just surviving the day as this may alter the approach you use with them. Some farmers respond well to data analysis, others prefer more of a conversational approach or even the use of visual on farm evidence (such as post mortems) and I think trying to utilise various different methodologies is key to getting farmers to start to engage with you. One underutilised method is the use of other farmers to champion good ideas and share them amongst their peers, which is why sending them to their mate down the road who implemented your idea can sometimes be the best way of convincing someone to change. And is possibly another reason why on farm meetings can be a huge success as everyone has barriers to implementing change and this can help break some of those down.

Another aspect of engaging the farmer is making sure that you involve the youngstock person/team in any discussions as fundamentally they are the people whom we are wanting to get to agree with us. Spending time with the team and explaining any data analysis/test results/ideas to the whole team is hugely beneficial and is a massive component of the herd health approach.

How do you prepare?

Fiona MacGillivray replies:

For a practice farmer meeting, it's great to be able to invite one or two farmers with relevant experience of the particular topic (e.g. reducing calf mortality or BVD control) to present a brief overview of their situation. In preparation, you can help the farmer to frame his experience as a relatable story; this can help the audience appreciate the key message/s you're hoping to convey and encourage them to consider changes on their own farms.

In my experience, when vets present a case study with their farmers as a ‘double act’, this can be a great way to include any quantitative data that may have been recorded as part of the investigation on farm. It also demonstrates ‘teamwork’ and the sense of partnership between vet and farmer.

For one to one discussion, I'd suggest initially trying to focus on establishing a rapport, through the use of open questions and positive body language (head tilt, nodding), as this helps develop a sense of trust, leading to more honest and open dialogue. Try to put yourself in the shoes (or wellies) of your farmer to give you a real opportunity to understand what motivates them and might be worrying them.

Asking questions such as ‘what do you feel is the biggest challenge at the moment with the calves’ can help start to get the conversation going. The use of reflection helps you to check you understood what was said and offers the farmer the chance to correct any misunderstandings you might have made.

Jolanda Jansen replies:

Make sure you have blocked time in both your agendas. Consultancy conversations should preferably not be interrupted by emergency calls. Make sure you know the facts and the history of the farm, and previous advice. Make sure you have your communication skills up to date. Think of a proper agenda and structure of the meeting. Prepare some open-ended questions to make sure the farmer keeps talking, instead of you preaching.

Katie Fitzgerald replies:

Often at the outset, calf health data can be sparse so the first step often involves setting up good data collection processes that are practical to be carried out on farm. Setting up whiteboards or simple to complete data collection sheets or establishing WhatsApp groups to records treatments can be useful. You can often collect data on passive transfer success and growth rates fairly quickly so having a system established to report results back to the farmer is important — failing to communicate results can quickly lead to lack of engagement so it's important to ensure the results are communicated to the right people including owners or managers and the team responsible for the calves. Well designed spreadsheets can allow you to quickly input data and generate useful reports to present to the farmer making it much more practical to give this feedback. There is often someone in the practice team much better skilled at designing these type of documents.

Ginny Sherwin replies:

The vast majority of work which we are involved in is the one-on-one chat with farms and actually the cup of tea at the end of a visit (RFV/bTB etc.) can be a fantastic opportunity to start the conversation, usually along the lines of ‘how are the calves doing at the moment?’. I always like to take the farmer some information about how his farm in performing, whether it is medicines use, growth rates, test results etc. as it shows the farmer that you are actively taking an interest in their farm and can give you an area to focus on, as you don't have to discuss everything in one go. It can also be a really useful way of feeding back positive information, as well as starting that conversation about an area of concern, which can then turn into a walk down to the calf sheds for a more in-depth conversation.

What in your experience should vets be aware of? Have you had any slip ups or made any mistakes that you have learned from?

Fiona MacGillivray replies:

With the benefit of learning more about communication skills and what makes people tick since leaving practice, I'd suggest trying not to write someone off as ‘difficult’ and presume they won't ever change. It's definitely worth trying to understand how your own approach to working with ‘difficult’ people might not be helping and seek to understand what it is that makes that person take the position they have. This is definitely where the recognition of what ‘colour’ traits (red/yellow/blue/green) a person may have and what communication style you have can help improve your interactions and sense of satisfaction.

Try to avoid going in with pre-planned actions and suggestions; the motivational interviewing communication style reminds us that both people in the conversation are ‘experts’. Often the farmer will already have considered different options or changes to make based on the problem or situation. Try to coach the farmer to explain what they have been thinking about already, why they might think it's possible to do or not to do it, then suggest you may have some ideas or examples that might be useful and relevant in this situation, if they'd like to hear this? This is where your expert veterinary knowledge comes in but first seek permission to share that knowledge, then check it has been understood and how they feel about it.

As Kat already pointed out, it's really important to watch out for the ‘righting reflex’. Most vets are trained or hard-wired to identify and then solve problems. However, it's worth understanding that the farmer might not perceive the same problem and actually, their priority might be totally different.

Before leaping in to offer advice and suggested solutions (and maybe write them a report!) for a problem you see as being a priority, it's worth realising, either that it might not even have occurred to the farmer or there's another reason they are not engaging in doing anything about the problem. Maybe they are having staffing problems or personal issues.

Trying to work from a report or plan you've created can cause the farmer to dig their heels in and resist any changes; this is a natural response for many people when faced with someone telling them they know what your problem is and how you should fix it.

In my experience, this is something that I always need to think about consciously before approaching a conversation where I expect change will be part of a discussion. Mentally preparing yourself, to try and remain open and non-judgemental to whatever the other person tells you, puts you in such a strong position to make the other person feel more inclined to open up and have a more honest conversation, where you both can work towards a solution/s.

Jolanda Jansen replies:

Please train your communication skills. We often assume that a lack of knowledge is the reason why farmers do not change their management. But more knowledge will not make them do things. Think of your own new year's resolutions. Will more knowledge help you achieve a healthy lifestyle? Often the knowledge is there already. Vets often assume that farmers are an empty cup of tea that needs to be filled with knowledge about diseases and prevention, but instead farmers are a cup full of knowledge, that just needs stirring a bit. By asking questions you affect the farmers' brain much more than by preaching the solutions. For example say: ‘Given the fact that you have limited time, what elso could you do to improve your youngstock health/reach your goal?’ Only if a farmer says ‘I don't know, you are the vet, tell me’ can you then give your advice. Make sure your advice is wanted and needed, farmers do not want to pay for unsolicited advice. Farmers don't care how much you know, until they know how much you care!

Katie Fitzgerald replies:

In calf health colostrum management is key and there is real variety in the success of passive transfer between units. Monitoring performance of passive transfer management is a key first step in any involvement in calf health. It shouldn't be overlooked that it is a tool to monitor herd performance, not to manage individual calves, and that a statistically significant sample size should be sampled before any assumptions are made about the effectiveness of the current management protocols.

Following on from colostrum, ensuring feeding protocols are suitable is frequently the biggest area that veterinary input can benefit the calves. Monitoring growth up to weaning using a weigh band can be cheap and effective. Failure to provide adequate nutrition leads to poor growth rates as well as poor immune function so whether your farmers' aims are to reduce disease, increase weights at weaning or target earlier age at first calving, early life nutrition is usually important in getting the right results. There are numerous resources available to assess feeding protocols including the AHDB calf feeding calculator (https://dairy.ahdb.org.uk/resources-library/technical-information/health-welfare/calf-milk-replacer-energy-calculator/#.XkAq5027LIU). As with every aspect of proactive calf health, measuring the outcomes (e.g. growth rates or weaning weights), influencing the management through assessing quality of milk replacer and feeding regimen, and monitoring the outcomes following management changes is key.

Ginny Sherwin replies:

I always think one of the biggest things for me is trying to get farmer compliance and trying to understand that despite what I think they should do/what is gold standard, it might just not be possible for this farm and therefore compromising will be key. If you can meet a farmer part of the way with an idea and involve them in the decision, then they are far more likely to buy into the idea and complete it. This is one of the reasons that it is usually beneficial to have these discussions in person, as you can start to see where the farmer is coming from and what barriers might exist. I like to follow up a visit with a short written summary of what we discussed and a bullet point list of recommendations or a phone call to check that the client is happy, as it gives the client time to think of other aspects of the plan which were not originially discussed.

I think one of my mistakes when I first started routinely doing youngstock herd health was excepting myself to have all of the answers for the specific farm I was dealing with and being able to solve all of their problems immediately by implementing lots of change. I have since realised that science has definitely not answered all of the questions about calf rearing for us and there is currently no plan of action which tells us that if we change this, then we will have healthy calves growing at target growth rates. The motivations of a farmer may also not be the same as mine and therefore instead of getting frustrated by this, I now try to come at the problem from their point of view and see what else we could do. I realised as well that farmers do not necessarily have the resources, both time and money, to do everything immediately and I usually try to leave the farm with a short, medium and longer term plan, with the aim of continued monitoring to see the impact of the changes made over time.

The key thing is to keep coming back to discuss what is happening with their calves and monitoring the data which we have.

Can you provide examples of where you have made the greatest impact?

Fiona MacGillivray replies:

Farmer meetings can offer one of the most effective ways to achieve buy-in from the other farmers in attendance. Inviting farmers to share their experience of a situation on their own farm presents a powerful opportunity for others in the audience to appreciate a ‘real-life’ scenario, perhaps with some aspects they can relate to and can stimulate some practical and insightful questions that perhaps we as vets might not have even considered.

In 2016 I was responsible for launching the BVDFree England BVD eradication initiative. This is a voluntary scheme, so it was really important to try and work with farmers who had experience of BVD control and BVD disease on their farms. As part of the launch, a number of farmer meetings were organised and we invited those farmers to speak about their experiences and why they believed the scheme was so important to the cattle industry. This offered other farmers the chance to hear about real-life cases of how BVD can cause devastating effects to farming businesses and become involved in the scheme themselves.

Jolanda Jansen replies:

We have developed many campaigns aiming to change farmer's behaviour. The most effective campaigns did not only distribute knowledge, but also pressed other ‘buttons’, like using social pressure or ‘nudges’. We tend to overestimate the effect of workshops and meetings. These are successful, but only for a limited number of farmers and they often attract farmers that have the least problems. For example, the reduction in use of antibiotics that we have achieved in the Netherlands was mainly because we changed the norm of what was considered good farming practice. By benchmarking farms and veterinary practices on their antibiotics use and sales, issues became suddenly visible. In the past using antibiotics was seen as good ‘stockmanship’ because you help animals and prevent diseases and increase production. Nowadays more and more farmers and vets see the use of antibiotics as a way to mask your management failures. Excessive use is not considered good farming practice anymore. That was a game changer.

Katie Fitzgerald replies: