A thorough clinical examination is a key factor in working towards a differential diagnosis list and eventually a diagnostic and treatment plan. Camelids can be challenging patients as a result of their stoic nature, making attention to detail imperative for the clinician.

History taking

Taking a thorough history is important, either before arrival on farm or animal-side, before clinical examination. This can provide insight into the owner's knowledge of, and worries about, the patient. For example, is the patient eating/drinking/urinating/defecating normally? Is there a change in habits for that patient, for example hanging back from the herd or spending more time lying down? Making contact before the visit also allows us to establish whether the animal is well handled or not, therefore informing whether extra pairs of hands are required. While the individual animal history is important, it is also useful to know the farm history. For example, are the animals vaccinated? Have they had similar problems before? Have there been any recent management changes? Are the animals adequately supplemented with vitamin D over the winter and what are the farm-specific parasite control strategies? Knowing when the last parasite screen was performed, the test type used, its results and any treatment is important. Could the animal be pregnant? Are the animals managed according to gender/life stage? What are the animals fed? Non camelid-specific feeds can lack essential minerals and therefore cause clinical issues which are often herd-wide. Knowledge of the farm set-up can start to prioritise differential diagnoses.

Arrival on farm

Camelids, although mainly kept as pets in the UK, are still farm animals which carry transmissible diseases including tuberculosis. Therefore, personal protective equipment should be worn as with all other farm visits. This should include easily disinfected wellies and waterproof trousers (or a coverall which can be discarded or washed after the visit) and a waterproof top. Although some clients will have ready-made disinfectant boot dips, it is prudent to also have your own method of disinfection, so carrying FAM 30 (or another DEFRA approved disinfectant), water and a brush is essential. If the patient is in a field on arrival, it is usually best to try to bring it into a contained area, as camelids are prey animals and usually exhibit a flight response in the presence of strangers. Herding camelids can be done effectively with a length of rope. Generally speaking, they will not challenge this and it can be used to move them into a desired area.

Initial assessment

Camelids are a prey species; this means that often, when restrained or contained in an unfamiliar area, they may not display the clinical signs described by the owner. Taking 5 minutes to assess the animal in the field on arrival can provide valuable information before physical examination. This is the best opportunity to assess posture at rest, which can give an indication of where the problem may lie. It is also useful to note whether the animal is with the herd or hanging away, whether it is recumbent and/or restless, its general mentation, any evidence of ataxia, how the head is carried and whether it is urinating/defecating normally. It may be possible to take a respiration rate at this point. Observation for any abdominal component to breathing and any nostril flaring can help localise any issues. Some clinical presentations will involve tremor which can be subtle and is much easier to see at a distance when the animal is relaxed than on close up clinical examination. As camelids are commonly pets, the owners will know what is normal for them as an individual and the astute among them will notice changes early on in the disease process. However, it is not uncommon for animals to present in a critical manner when early warning signs of disease have not been identified; for example, condition loss commonly goes unnoticed until there is a dramatic change.

Restraint

It is helpful to have an experienced handler present as not all camelids will be used to being restrained or touched, especially in places like the axilla. Responses to handling vary from animal to animal and can include: rearing up, cushing (sitting) down, spitting and kicking. While the majority of animals will accept most of a standard clinical examination without much reaction, it is important for both vet and handler to be aware of the common flight tactics. The most common method of restraint for veterinary procedures is pictured in Figure 1. Restraining high up on the neck allows for maximum control of the animal, placing a hand on the withers and applying gentle downward pressure dissuades the animal from rearing or jumping up. There are other commonly used restraint methods used by owners and vets alike – these methods usually come under the umbrella term ‘camelid dynamics’ (Bennett, 2022). These methods of working with camelids are designed to be less intrusive and force-based than other restraint methods; one example, the bracelet hold, is shown in Figure 2.

General clinical examination

There are multiple styles of clinical examination that can be adopted (Jackson and Cockcroft, 2008), of which the ‘top to toe’ or systems-based approach would be the authors preference. Starting at the top:

- There should be no nasal or ocular discharge

- It is important to remember that persistent discharge may not be strictly ocular in origin. Blockage of the nasolacrimal duct or malformation thereof can also lead to persistent lacrimation. Imperforate ducts are more commonly seen in cria; while animals who are normal, and subsequently develop epiphora, are more likely to have a blockage

- Check around the muzzle/ears and bridge of the nose for hair loss, which can occur secondary to mite infestation

- Ocular mucous membranes should be salmon pink

- The FAMACHA scale can be implemented when assessing colour (Storey et al, 2017). This is important as there are pathologies aside from parasites which will commonly lead to anaemia, such as the presence of C3 ulcers

- Injected or dark mucous membranes can indicate some level of septicaemia, which would need prompt investigation and treatment

- Cornea should be bright and clear

- Oral mucous membranes should be moist

- In animals with dark buccal mucous membranes, the ocular and vulvar (in females) membranes are good alternatives

- If possible, check for fighting teeth:

- Fighting teeth are a triad of canines either side of the mouth. They are very sharp and can be used during fights to cause harm

- Fighting teeth are larger in entire males and eruption is associated with the onset of puberty (Niehaus, 2022).However, they can also be present in females as well as castrated males

- Check for facial symmetry:

- Molar abnormalities can often be palpated externally by running your hands down the outside of the jaw

- Camelids are prone to tooth root abscesses, which are much easier to treat when diagnosed early. Any facial swelling or asymmetry of the mandible or maxilla would merit a thorough oral examination under sedation as well radiography of the jaw

- Check there is airflow through both nostrils by holding a piece of tissue/fibre in front of the nostril and watching for movement

- Check for ptosis

- Check the symmetry of the lips

- Check the symmetry of ear carriage

- The neck should be held straight, check for palpable deviations of the spine

- Neck and head carriage should be upright – a horizontal neck can indicate issues such as arthritis

- Check the front legs for symmetry, as deviations could indicate trauma or hypovitaminosis D. Check for hair loss on the caudal aspect of the carpo-metacarpal joint, as this can indicate the presence of mites

- Legs should be straight, any deviation at the carpi and/or swelling of the joints can indicate a vitamin D issue and possible rickets, as well as a possible joint ill

- Foot pads should be smooth and unbroken, overlayed by a nail which is not cracked or overly long

- Range of motion of the forelimb joints can either be assessed at this point or after the initial examination

- Body condition score

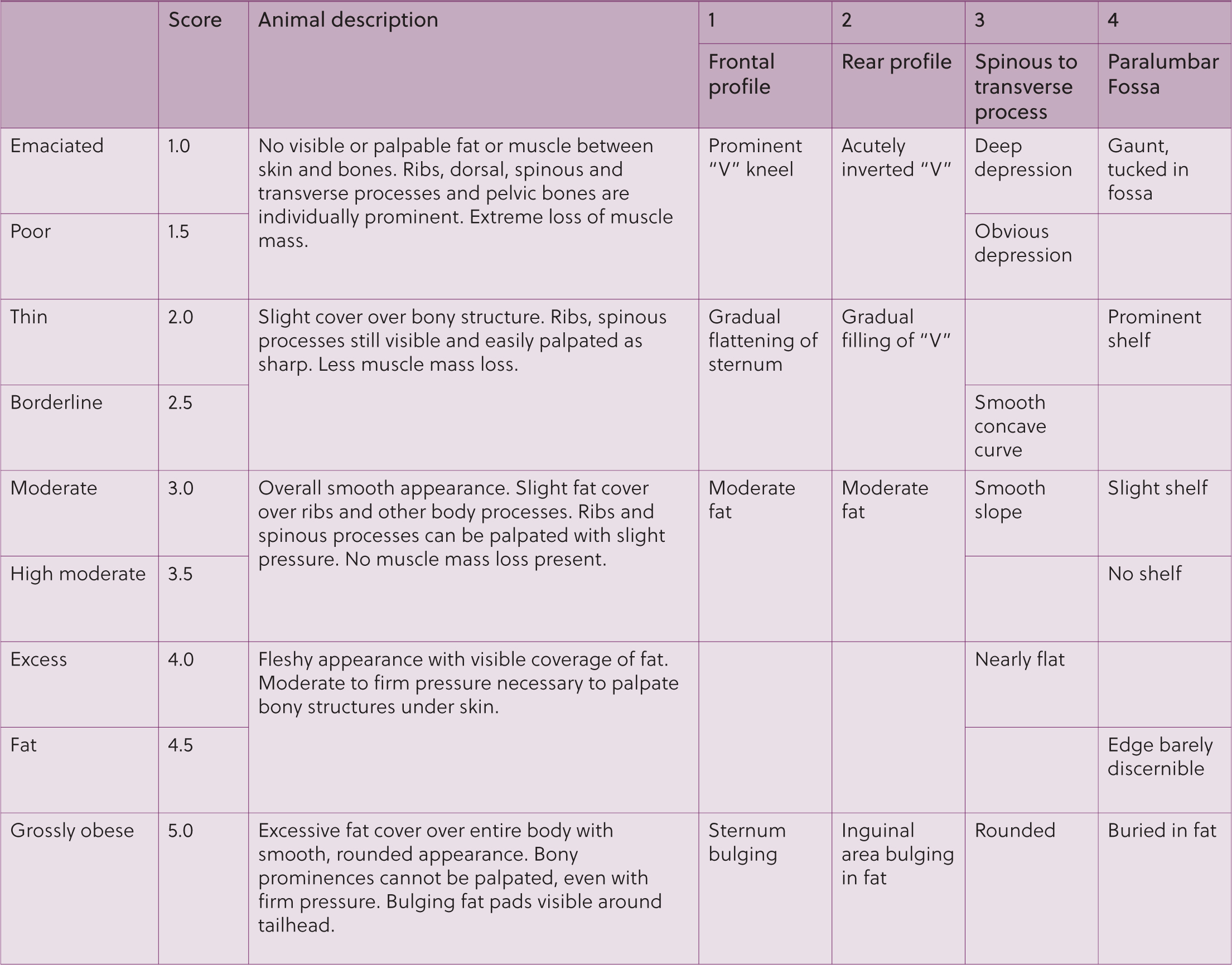

- This is very important as it is a more standardised way of assessing condition than weight. In the UK, a score of 1 (emaciated) – 5 (grossly obese) is commonly used, see Figure 3 (Van Saun, 2023).

- Palpation over the caudal rib cage is important. You should be able to feel the ribs without the need for excessive pressure

- Palpation of the lumbar transverse processes should also be performed to assess for fat coverage in this area. The palm of the hand should lie flat between the dorsal spine and the transverse process when in optimal body condition. This angle becomes concave in underconditioned and convex in overconditioned animals

- Thoracic auscultation:

- Respiration rate should be between 10 and 30 breaths per minute (Jones and Boileau, 2009)

- Lung sounds are generally quiet in camelids, although they may be more audible in thin animals, but loud lung sounds are indicative of pathology (Whitehead, 2013)

- Respiratory effort is usually minimal in camelids, an abdominal component to respiration suggests pathology either of the lungs themselves, or of other structures such as the diaphragm

- There should not be any audible upper respiratory noise, either from a distance or on auscultation of the larynx

- Camelids are semi-obligate nasal breathers; therefore, mouth breathing is abnormal unless there is a disease process preventing nasal breathing, or the animal is stressed/has been spitting.

- The fleece should be parted to allow for better contact of the stethoscope diaphragm with the body wall

- Cardiac auscultation:

- Heart rate should be between 60 and 90 beats per minute (Niehaus, 2022)

- Cardiac auscultation is usually similar to other farm species. However, camelids are prone to murmurs, so careful auscultation in a quiet environment is important

- Common camelid heart defects include, but are not limited to: septal defects, these are more commonly heard on the right hand side if they are ventricular in origin (Cebra and Sisson, 2014); outflow tract obstructions which are best auscultated on the left at the base of the heart; atrioventricular valve insufficiency where the valve affected determines whether the murmur is heard better over the left or right apex (Cebra and Sisson, 2014)

- It is important to remember that not all heart conditions will present with a murmur – for example, a large ventricular septal defect may not produce a loud murmur while still being clinically significant (Margiocco et al, 2009).

- Increased jugular fill and pulses are difficult to assess in this species as a result of the anatomical location being much deeper in the neck than other farm species

- There is a more sparsely fleeced area in the axilla where close skin contact is more easily obtained

- Its is also possible to palpate a femoral pulse to check for synchronicity with the heart rate

- Auscultation of the left abdomen:

- The left abdomen is primarily filled by compartment 1. This is analogous to the rumen in ruminants

- It turns over more quietly than in ruminants and also more frequently

- It should turn over 3–4 times per minute in a normal alpaca/llama. This may increase after feeding (Niehaus, 2022)

- Normal camelids should regurgitate and chew cud, this may cease when stressed under clinical examination but should be visualised at rest from your hands-off initial assessment

- Auscultation of the right abdomen:

- Borborygmi can generally be heard, although more quietly than in other true ruminant species. The right abdomen is occupied by compartments 2 and 3 as well as the small intestines

- Faecal output is a good indication of intestinal function, standing an animal on concrete for a period of time will allow assessment of both urine and faecal output

- Take the temperature

- As with all animals, it is important to insert the thermometer at least an inch into the rectum and ensure it is pressed against the rectal wall rather than embedded in faeces

- Rectal temperature should range from 37.5–38.9°C

- Repeat the reading more than once if unsure whether it is accurate

- Assess the vulva in females to see that there is a normal opening

- This is also a good place to assess the colour of mucous membranes

- Assess the mammary gland for any evidence of heat, swelling or pain; particularly pertinent if the animal has lost a cria recently

- Assess the testicles in males to check both are present, firm and freely mobile within the scrotum

- Assess the penis. There should be no swelling around the prepuce and no discharge. Check also for abrasions in the area which may indicate trauma

- Take note of any fleece soiling at this point in the examination. Normal camelid faeces are pelleted and therefore should not stain the fleece, any staining and/or wetness of the fleece around the hidlimbs merits further investigation. Soft faeces can indicate significant pathology but may also be secondary to stress and/or a change of diet. Sampling for parasites is always prudent

- Taking a faecal sample is very often warranted in sick animals, as parasites are one of the most common causes of illness in this species. Samples can be taken directly from the rectum with lube-covered fingers. It is important to send these samples to labs which are accustomed to dealing with camelid faeces, as use of the Modified Stoll's technique is gold standard

- Assess the hindlimbs for hair loss as described for the forelimbs

- Assessment of the hindlimbs for range of motion is important, especially in older animals, as pelvic limb arthritis is common. Feeling for crepitus, joint effusions and patellar stability can help localise lesions. Symmetry of the pelvic musculature can give an indication of the chronicity of lameness

- Assess the nails and foot pads of the hindlimbs as described for the forelimbs.

Neurological examination

There are many potential causes of neurological disease in camelids. As with other species, neurolocalisation is important to refine the differential diagnoses list. A thorough history of any symptoms, along with details of speed of progression can help begin to localise the lesion. It is important to check cranial nerve function and proprioception, as well as differentiating ataxia from weakness (Whitehead and Bedenice, 2009).

Starting at the nose and working caudally, we can assess for any visible asymmetry of the nose, lips and ears and whether the head carriage is central or not. It is important to ascertain the duration of onset of any abnormalities detected and to distinguish new from congenital issues (eg wry face in cria). Examination of the eyes can yield important clinical information; assessment of menace response, palpebral reflex and pupillary light reflex can help prioritise differential diagnoses. For example, in cases of cerebrocortical necrosis, central blindness is an associated clinical sign, which is evident on clinical examination as an absent menace response (Bedenice and Whitehead, 2016a). The normal camelid will show both a direct and consensual pupillary light reflex (Bedenice and Whitehead, 2016b). They will blink when touched at the medial canthus as well as when a finger is moved towards the eye. Facial sensation can be determined by touching the lips individually and using closed forceps to touch the inside of the nasal passage bilaterally. Facial sensation can also be assessed by using forceps or a finger inserted into the ear canal. This should normally illicit a head shake or attempt to withdraw the head. Moving caudally, the neck should be palpated for symmetry, subluxations and fractures. Malformations of the cervical vertebrae are not uncommon in camelids and can be readily palpated. Radiographs can reveal abnormalities to inform prognosis in these cases. Pathology can also present more caudally in the vertebral column and there are some simple tests that can be performed in the field to assist with lesion localisation. With the patient in lateral recumbency withdrawal, reflexes can be tested by using haemostats to pinch the distal end of the digital pad (Bedenice and Whitehead, 2016b). The patellar reflex of the hindlimbs can be assessed by percussing the middle patellar tendon. These tests should be performed on the uppermost limb before turning the patient to perform the same tests on the contralateral limbs for a more reliable result. It is also possible to assess proprioception. These tests should be performed in the standing position. Knuckle each foot individually such that the animal stands on the cranial aspect of the metacarpophalangeal joint; a normal animal should reposition the foot almost immediately. Likewise, when the leg is placed in an abducted position the animal should bring it back to centre. Neurological examination of camelids is not always a straightforward procedure, and having a more experienced clinician on hand can be invaluable for these more complex cases.

Conclusions

Camelids can be tricky patients as a result of the fact that they are prey species and try to hide illness until it becomes critical. A holistic view, taking into account the animal's and farm's history, a distanced observation and clinical examination, can inform on the best course of action going forward. It is helpful to have an experienced handler present for examination, as not all camelids will be used to being restrained or touched.

KEY POINTS

- A thorough history can signpost areas to investigate further on your clinical examination.

- Distanced observations are invaluable to building a full clinical picture.

- Camelids are very stoic in nature, and will try to hide illness when examined.

- The presence of diarrhoea is often significant – faecal sampling for parasites is prudent.