Abomasal ulcers are defined as an erosion of the abomasal mucosa into the submucosal layer. Depending on the severity and chronicity of an ulcer, affected animals may have only subclinical disease, but clinical disease can range from mild non-specific signs, to fulminant peritonitis, sepsis and death. The prevalence of either subclinical or clinical abomasal ulcers in adult cattle is largely unknown. Studies have reported prevalences of 20.5, 48.5 and 84% in dairy cows at slaughter (Braun et al, 1991a; Hund et al, 2016; Munch et al, 2019), and 65.9% in fattening bulls at slaughter (Hund et al, 2016). Given these findings it is feasible that cows suffering from abomasal ulcers that are causing clinical disease are presented to practitioners with reasonable frequency, but the non-specific clinical signs means this condition can be easily misdiagnosed.

Aetiology of the disease

Many possible causes of abomasal ulcers have been suggested and investigated but the aetiology of them is still not definitively known. It is commonly accepted that a disruption in the balance between protective and corrosive influences on the abomasal mucosa underlies the condition. Stress and nutritional influences are two of the main factors thought to underly the initiation of abomasal ulceration in many adult cattle.

Stress, including the physiological strain of lactation (specifically negative energy balance) or management changes such as the mixing of groups of cattle, is known to affect multiple physiological systems. Concurrent disease is another cause of increased physiological stress and has been found to be associated with an increased risk of abomasal ulceration (Braun et al, 1991b), and in particular the presence of bleeding or perforated ulcers (Palmer and Whitlock, 1983; Palmer and Whitlock, 1984). In times of stress, cortisol, pepsin and gastric acid secretion are increased and the secretion of prostaglandin is decreased. Prostaglandins act to protect the gastric mucosa as they stimulate epithelial cells to release more bicarbonate and mucus, they reduce the permeability of the gastric epithelium which reduces ‘back diffusion’ of gastric acids, and they are potent vasodilators, which allows the gastric mucosa to respond better to damage (Wallace, 2008). These stress-induced changes, therefore, result in reduced protection and increased erosive influences on the abomasal mucosa, which can result in the formation of ulcers.

Feeding is also an important factor as a sustained reduction in the pH of the abomasal contents can result in damage to the mucosal surface. High concentrate feeding, which results in the production of high volumes of volatile fatty acids that cannot all be absorbed by the rumen (and can themselves be associated with ruminitis (Rossi and Compiani, 2016)), results in overflow of these acids into the abomasum, decreasing its pH. Alongside this, the ruminal acidosis results in increased histamine production, which in turn increases abomasal acid secretion, further contributing to a decreased abomasal pH.

Various infectious agents have been suspected to contribute to the formation of abomasal ulcers in cattle including Clostridium perfringens, Campylobacter jejuni and Helicobacter spp., which have been implicated in contributing to the condition in humans and pigs (Friendship et al, 1999), as well as various fungal agents. None of these have, however, been conclusively linked to abomasal ulceration in either cows, bulls or calves (Hund et al, 2015), therefore any influence they do have is currently not undersood.

The use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), which inhibit the production of prostaglandin, has been shown to result in an increased risk of gastric ulceration in a number of other species (Nakagawa et al, 2010; Pedersen et al, 2018), although not yet in cattle. It is thought highly likely that the same mechanisms are a risk to the formation of abomasal ulcers in cattle as the abomasum is effectively the ‘true’ stomach in these species. The risk of gastric ulceration is primarily mediated through the inhibition of isoenzyme cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1), which is found more in the gastrointestinal tract relative to COX-2, which is mainly at sites of inflammation. The use of NSAIDs that preferentially inhibit COX-2 may reduce the risk of the associated gastrointestinal side effects. Meloxicam is the most reliably preferential COX-2 inhibitor licensed in cattle, with carprofen being more COX-2 selective than flunixin, which is non-selective (Miciletta et al, 2014), as is ketoprofen (Donalisio et al, 2013).

Types of ulcer

A classification system has been introduced to grade the different severity or chronicity of abomasal ulcers (Smith et al, 1983) and subsequently modified to include four subtypes of type 1 abomasal ulcers (Braun et al, 1991a), see Table 1.

Table 1. Grades of severity or chronicity of abomasal ulcers

| Ulcer type | Feature | |

|---|---|---|

| Type 1 | 1a | Non perforating ulcer: minimal mucosal defects |

| 1b | Non-perforating ulcer: some local haemorrhage | |

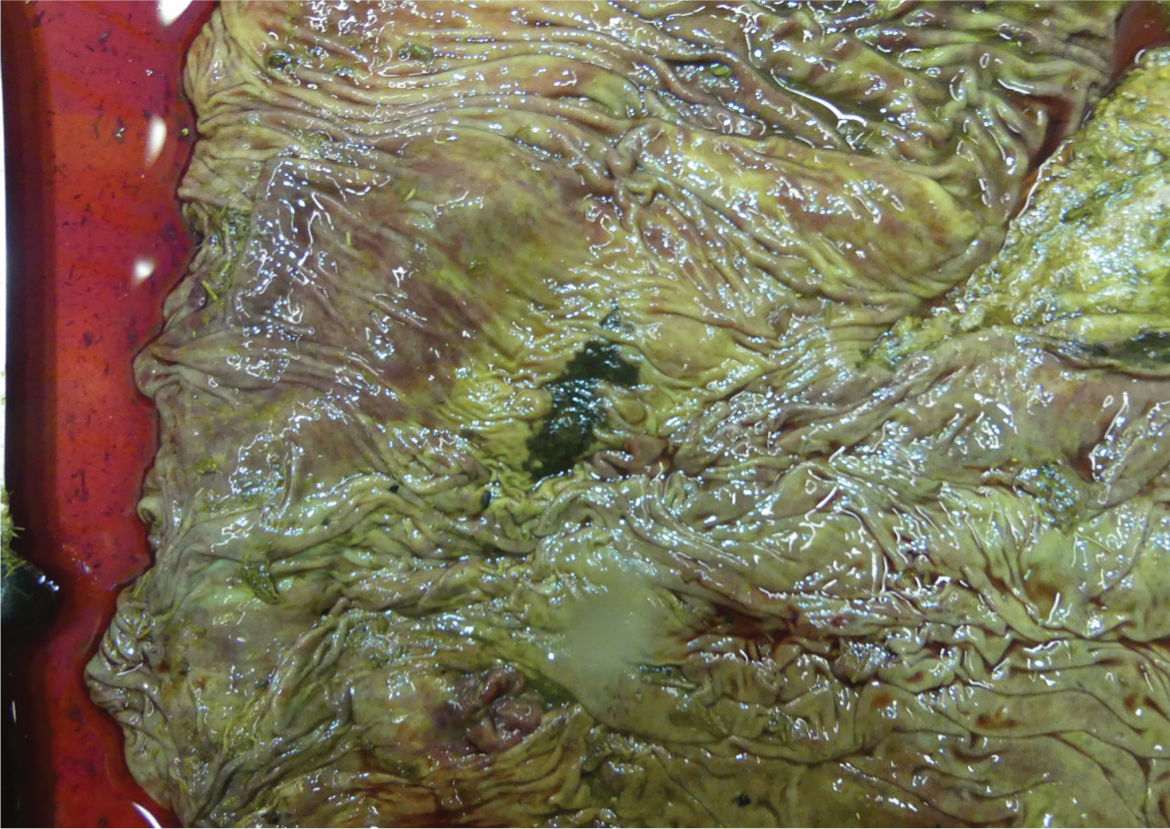

| 1c | Non-perforating ulcer: crater like and covered with fibrin (Figure 1) | |

| 1d | Non-perforating ulcer: radial wrinkles with a central point | |

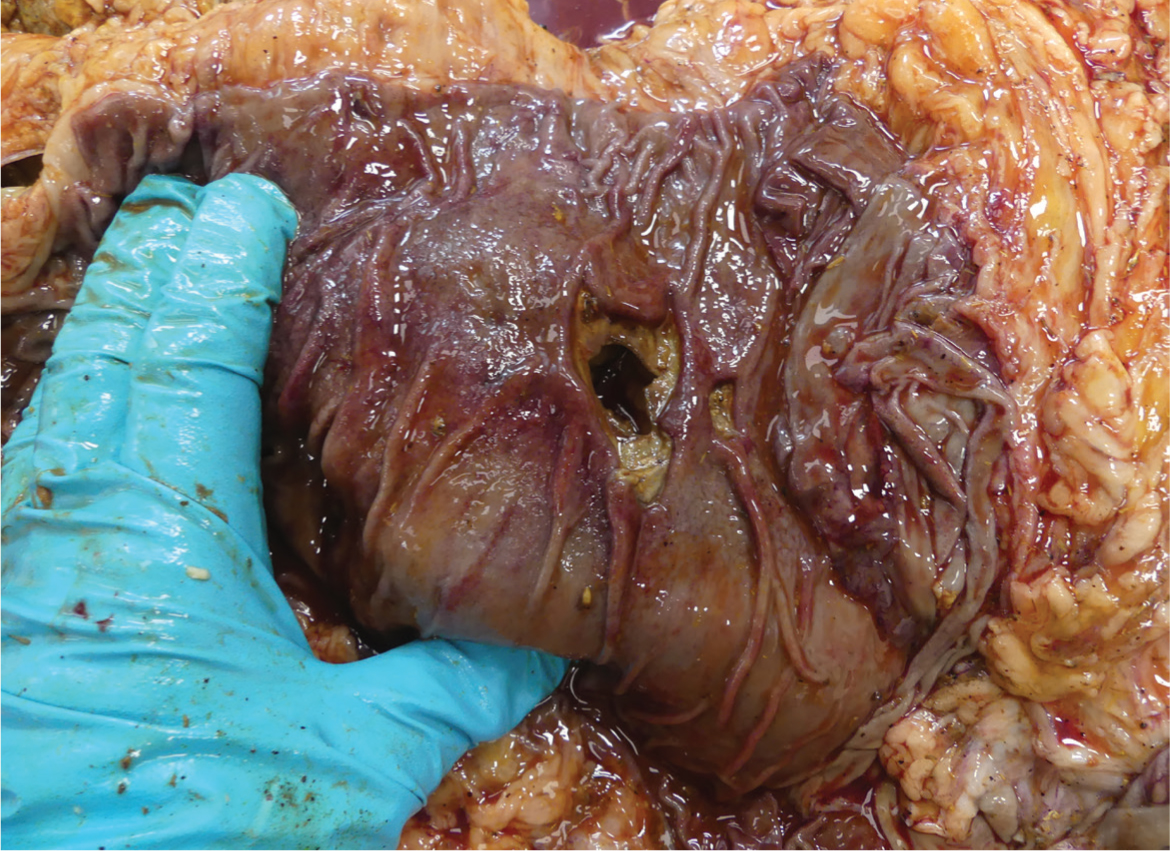

| Type 2 | Haemorrhagic (Figure 2) | |

| Type 3 | Perforated with acute localised peritonitis | |

| Type 4 | Perforated with diffuse peritonitis (Figure 3) | |

| Type 5 | Perforated with peritonitis within the omental bursa | |

Clinical signs

The clinical signs associated with abomasal ulcers in cattle can be varied and non-specific, and can also be observed in cows suffering from conditions other than abomasal ulceration such as traumatic reticulo-peritonitis (TRP). Clinical signs that have been found to be most accurate for the diagnosis of an abomasal ulcer in one study are colic, ruminal atony and black faeces (Braun et al, 2020a). These clinical signs were almost always (99.0–99.5%) normal in healthy animals. The same study also identified other clinical signs were found to indicate illness (either TRP or abomasal ulcers) because of their low frequency of occurrence in healthy cows. These clinical sigs were: an arched back and bruxism; abnormal demeanour; rectal temperature <38.0 or >40.0°C, a heart rate over 100 beats per minute (bpm) and a respiratory rate over 55 breaths per minute. Positive percussion and ballottement on the right side was found significantly more frequently in cows with an abomasal ulcer, however, it was also present in 10% of apparently healthy cows. Other clinical signs that were not specific for ill cows and occurred with relative frequency in animals considered healthy by the investigators, included reduced ruminal movements (seen in 13%), rectal temperature 39.0–39.5°C (25%), congested scleral vessels (29%) and at least one positive withers pinch or bar-drop test (44%). It seems that there is not a single clinical presentation that can be used for the diagnosis of abomasal ulcers, however, it can be seen that a combination of clinical signs that are rarely found in healthy animals would be a strong indicator.

Some clinical signs that occurred with high frequency in ill cows in the study by Braun and colleagues (Braun et al, 2020a) were much more specific for the presence of an ulcer or a particular type of ulcer:

- Ruminal atony was much more common in cows with abomasal ulcers than those with TRP

- Black faeces were more likely to be indicative of a type 2 (haemorrhagic) ulcer

- An arched back was found significantly more often in cows with ulcers of grade 4 and 5 than in cows with TRP or ulcers of other grades

- Pale mucous membranes were more likely in cows with type 2 or 4 ulcers

- Abdominal guarding was present in 100% of cows with type 5 ulcer (although seen commonly in other ill cows) and so type 5 ulcers could be ruled out if this clinical sign is not present.

Diagnostics

There is not a single definitive test for the diagnosis of abomasal ulcers in cattle. However, when used alongside the findings of a thorough clinical examination there are a number of tests that can contribute to building a picture of the likelihood that a cow has an abomasal ulcer.

Certain blood biochemistry and haematology parameters are consistently abnormal with ulcers of all grades, whereas some parameters may be more indicative of certain grades of ulcers. Hypokalaemia is the most consistent biochemical abnormality in cows with all types of ulcers (Braun et al, 2019a, 2019b, 2020b, 2020c; Gerspach et al, 2020). Azotaemia is also a common feature in cows with type 1, 2, 4 and 5 ulcers. Cows with Type 1, 4 and 5 ulcers more commonly have a high haematocrit, likely associated with dehydration, whereas cows with type 2 ulcers are more likely to have a low haematocrit, associated with bleeding from the ulcer itself (Braun et al, 2019a). The haematocrit of cows with type 3 ulcers is most commonly within normal limits (Gerspach et al, 2020). Hypoproteinaemia is also a feature of cows with type 2 ulcers (Braun et al, 2019a). A shortened glutaraldehyde test and hyperfibrinogenaemia were more common findings in cases of type 3 and type 4 abomasal ulceration owing to the presence of peritonitis (Braun et al, 2019c; Gerspach et al, 2020). Increased chloride concentration of ruminal fluid (<26 mmol/litre) is also associated with abomasal ulcers.

Faecal occult blood tests are said to be useful for the diagnosis of abomasal ulcers, however they are poorly sensitive for acute lesions (0.40) and non-specific (0.71) for this disease in general. These tests have been shown to have no diagnostic value in detecting superficial ulcers or scar tissue and a positive test is not diagnostic for abomasal ulcers (Munch et al, 2020), although can contribute to the clinical picture, particularly the suspicion of bleeding (type 2) ulcers. One study found the positive predictive value of abdominal pain alongside a haematocrit <24% and occult blood in the faeces to be 100%, although only a sensitivity of 15% (Smith et al, 1986).

Blood pepsinogen has also been found to be significantly higher in cows with abomasal ulcers because of the increased ability of the pepsinogen to leak into the blood across the damaged abomasal wall (Mesaric, 2005). Increased blood pepsinogen can also be increased in cases of parasitism and so is not solely diagnostic for abomasal ulceration. In adult cattle, particularly those in dairy systems, parasite burden is unlikely to be very high and so in this cohort of animals a high blood pepsinogen should raise the suspicion of an abomasal ulcers.

Ultrasound examination of the abomasum can be performed, although because of the abomasal folds and abomasal contents, visualisation of ulcers in the mucosa is difficult, particularly for clinicians in the field and those without access to high-definition ultrasound machines. Percutaneous ultrasound-guided sampling of the abomasal contents for occult blood testing is theoretically possible, however, has not been validated and could itself cause bleeding into the abomasal lumen (Hund and Wittek, 2018). Abdominocentesis can be helpful to diagnose peritonitis associated with type 3,4 and 5 ulcers, although a laparotomy is the only way of definitively differentiating these grades of ulcer. Exploratory laparotomy will also aid in determining the prognosis for an individual animal depending on the extent and chronicity of any peritonitis present.

Treatment and management

While in non-ruminant species and in pre-ruminant calves, the use of pharmacologic treatments such as antacids, histamine type-2 receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors have been shown to have some beneficial effects in protecting the mucosa of the stomach (or abomasum in calves), there is little or no evidence that these treatments have any effect in adult cattle, and many of these drugs do not have set maximum residue limits (MRLs) and so cannot be used in food producing animals. The use of histamine type-2 receptor antagonists has shown some promise as the abomasal pH of steers has been found to be increased for 60 minutes and 4 hours after the administration of intramuscular ranitidine and intravenous famotidine, respectively (Wallace et al, 1994; Balcomb et al, 2018). However, the efficacy of famotidine reduced with subsequent treatments and so the use of these drugs as treatments in the field (regardless of the fact that there is no MRL for these drugs) would be limited because of their short-acting effects. The proton pump inhibitor pantoprazole has been administered to hospitalised ruminants to reduce the risk of gastric ulceration and has been found to have minimal adverse effects (Smith et al, 2020). Currently no pharmacokinetic data exist for its use in cattle, although it has been shows to have some efficacy in camelids and foals (Ryan et al, 2005; Smith et al, 2010). The use of prokinetic drugs, such as metoclopramide and erythromycin, have been proposed to remove acidic abomasal contents by increasing emptying, however, not only is there no evidence for the efficacy of these drugs for this purpose, but the use of metoclopramide is banned in food producing species (and is therefore illegal), and the use of erythromycin (a macrolide antimicrobial) for this indication would be off-license, and should be carefully considered on grounds of responsible antimicrobial use.

Treatment of cattle with diagnosed or strongly suspected abomasal ulcers should focus on symptomatic and supportive care, as well as the treatment of any concurrent diseases. Initial treatment should focus on correcting hypovolaemic shock with aggressive intravenous fluid therapy. Administration of intravenous glucose and calcium borogluconate have also been used to treat cows with successful outcomes (Braun et al, 2019a, 2019b). Blood transfusions should be considered in cows for which type 2 ulcers are suspected and an acute drop in haematocrit to below 12% is seen (Balcomb and Foster, 2014). Other clinical signs including pale mucous membranes, tachycardia above 100 bpm, inability to stand and dyspnoea should also be considered indicators for transfusion in cases where haematocrit measurement is not possible (Gerspach et al, 2020).

Surgical treatment of perforated abomasal ulcers with associated left displaced abomasum has been described, although the survival rate of this procedure was only 14% (Cable et al, 1998). Laparotomy of cows with perforated (type 3, 4 and 5) ulcers is primarily useful for ascertaining the degree of associated peritonitis and to inform decisions regarding management of the case. Cows with type 3 ulcers should be considered for euthanasia because of poor survival rates (Braun et al, 2019b) and a guarded prognosis should be given if treatment is undertaken. Treatment of cows discovered to have type 3 ulcers by laparotomy should include aggressive intravenous fluid therapy and glucose administration, systemic antibiotic treatment and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) pain relief.

Cows with type 4 and 5 ulcers should be euthanased immediately because of the grave prognosis associated with these diagnoses. Exploratory laparotomy may be the only way of reaching a definitive diagnosis in many of these cases.

Prognosis

The prognosis for cows with abomasal ulcers is hugely dependent on the type of ulcer that is present. It is very likely that type 1 ulcers can remain subclinical in many cattle given the high prevalence (84%) found in Danish dairy cows at slaughter (Munch et al, 2019). In fact, non-perforating ulcers have been found to be associated with being culled later in their lactation and higher weight at slaughter in one study (Nielsen et al, 2019). Conversely, another study of cows diagnosed with type 1 ulcers in a hospital setting resulted in 83% being euthanased and only 8.5% being discharged from the hospital. This may reflect different prognoses for cows with clinical versus subclinical presentations of this disease.

The prognosis for cows with type 2 ulcers will depend largely on the intensity of care provided. Outcomes of 67% of treated cows recovering have been reported, however this was in a hospital setting and all the cows had received intensive treatments. Poorer outcome rates should be expected in the field where similarly intensive treatment regimens may be economically and logistically unfeasible.

The prognosis for type 3 ulcers is significantly poorer than that of type 2 ulcers, likely because of the less specific nature of the clinical signs associated with this grade of ulcer as well as the more profound systemic effects of the associated peritonitis. In a hospital setting the survival rate of cows with type 3 ulcers was 20%, despite intensive treatment, and only 17% remained productive at 2 years after treatment (Braun et al, 2019b).

The prognosis for cows with type 4 and 5 ulcers is hopeless. In two studies by the same author all cows with type 4 and 5 ulcers were euthanased (Braun et al, 2019c, 2020c).

Conclusions

Abomasal ulcers are likely to be relatively common in the UK cattle population. Practitioners should be mindful of this condition when examining cattle presented with any of the associated clinical signs, in particular those displaying colic, ruminal atony, an arched back or black faeces. If an abomasal ulcer is suspected, employing further diagnostic tests as an adjunct to a thorough clinical examination can help to increase the likelihood of a correct diagnosis being made. Blood work to look for hyperkalaemia, azotaemia and a high (type 1,4 and 5 ulcers) or low (type 2 ulcers) haematocrit, as well as the review of other biochemical parameters, may assist a diagnosis. Ultrasound imaging or a peritoneal tap may help to further the diagnosis in some cases, although in many, particularly of type 3, 4 and 5 ulcers, an exploratory laparotomy may be the only way to reach a definitive diagnosis. Aggressive medical management of cows suspected to have type 1 or 2 ulcers may be feasible, although a good prognosis can never be given if an abomasal ulcer is suspected. If a type 3 ulcer is suspected a poor prognosis should be given and euthanasia of the animal should be considered. Euthanasia is the only option that should be recommended for cows diagnosed with type 4 or 5 ulcers on welfare grounds.

KEY POINTS

- The prevalence of abomasal ulcers in the UK cattle population is unknown.

- It is likely that abomasal ulcers are under diagnosed because of the non-specific way in which they present.

- A thorough clinical examination should help to increase or decrease the suspicion of an abomasal ulcer.

- Further diagnostics including blood biochemistry and a haematocrit analysis can further assist to increase or decrease the suspicion of an abomasal ulcer.

- Occult faecal blood tests have poor sensitivity for the diagnosis of abomasal ulcers.

- Exploratory laparotomy will often be the only way to definitively diagnose type 3, 4 or 5 ulcers, and should be considered if these are suspected to facilitate decision making and reduce the animal suffering in the face of a poor (type 3) or grave (types 4 and 5) prognosis.