Perinatal lamb mortality is a significant issue in terms of welfare and economics on sheep farms worldwide (Dwyer, 2008) and has been reported to have remained stable at 15–20% over the past four decades (Dwyer et al, 2016). A UK study reported an overall lamb mortality risk of 7% across 108 sheep farms (range 3.3–8.3%) (Binns et al, 2002), with most preweaning lamb deaths occurring within the first week of life (Hybu Cig Cymru Lamb Losses Project, n.d.; Nowak and Poindron, 2006). An increased risk of neonatal mortality has been associated with septicaemia as a result of inadequate colostrum intake, starvation and death caused by exposure hypothermia (Chaarani et al, 1991; Green and Morgan, 1993). The transfer of colostral antibodies to the lamb is vital because of the epitheliochorial placenta preventing the transfer of maternal antibodies in utero (Brambell et al, 1970; Wooding et al, 1986). The level of IgG in lamb blood is directly related to colostrum intake and quality (Shubber et al, 1979a, 1979b). Colostrum production occurs prior to parturition and contains both important immunoglobulins for the immunologically naïve lamb, as well as a high level of fat to prevent starvation (Banchero et al, 2015; Kessler et al, 2021). Colostrum yield is dependent on adequate supplies of both energy and protein in the last 3 weeks of gestation (Dwyer et al, 2016; Hinde and Woodhouse, 2019).

There has been limited information available as to the IgG content of ovine colostrum, which has commonly been assumed to be equivalent to dairy cows (Dwyer et al, 2016; Hinde and Woodhouse, 2019). However a recent comparative study showed that, despite having both higher total protein and fat content, ovine colostrum, at IgG of 30.1±13.9 mg/ml (n=100 samples) has a significantly lower IgG concentration than bovine colostrum at 94.0±38.3 mg/ml (n=108 samples)(Kessler, 2021). It has been suggested that over 20 mg/ml IgG is the target level for sheep samples (Agenbag et al, 2021; Kessler et al, 2021). To ensure successful passive immune transfer it has been suggested that lambs should consume at least 30 g IgG in the first 24 hours of life (Alves et al, 2015).

Measurement of colostrum quality using a Brix refractometer is a common practice on dairy cow farms, however it has not been common practice on sheep farms (Agenbag et al, 2021). Kessler et al showed that for sheep, goats and cattle, Brix values were highly correlated with IgG and protein concentrations (r=0.75 and 0.87 for ovine samples) and reported that the optimal Brix cut-off with the greatest accuracy was 26.5% for sheep (75% sensitivity and 91.3% specificity) (Kessler et al, 2021). This contrasted with samples collected from intensively housed Lacaune dairy sheep where lower cut-off values were suggested; however this study did not aim to determine the cut-off Brix value, and determined further research was required (Torres-Rovira et al, 2017)

Variation in colostral IgG has been reported between ewes, with factors such as dam age, litter size, udder health, time of year, breed, genetics and late gestation nutrition having varying levels of significance in different studies (McNeill et al, 1988; Banchero et al, 2015; Kessler et al, 2019; Agenbag et al, 2021).

This study aimed to encourage commercial Welsh sheep farmers to focus on colostrum quality and quantity to improve lamb survival, while determining whether colostrum quality was a problem and which factors had the greatest impact.

Materials and methods

Farms

One hundred and forty seven sheep farmers across Wales were recruited based on involvement with a Farming Connect discussion group. These farmers were enrolled in the study and received training in the use of the Brix refractometer. This was in the form of an online meeting and farmers were sent a video (Colostrum project & using the Brix) on the standard operating procedure for using the refractometer.

Data collection

The participants were asked to collect a colostrum sample from ten ewes at the start of lambing and ten ewes at the end of lambing. They were asked to collect and to test samples within 6 hours of lambing from twin and triplet lamb-bearing ewes, unless their flock scanned with the majority of ewes having singles. A Brix refractometer was used for testing. The colour of the colostrum (a range of colours from white to yellow) and ease of stripping the colostrum (good, average or hard) were recorded alongside the ewe's identification number, age, body condition score (BCS) and a description of the udder. The lambing environment (indoors or outdoors), number of lambs born and number of those born alive were also recorded. The farmer was also asked to submit information via a questionnaire, regarding the diet of the ewes 6 weeks prior to lambing. Data were compiled and descriptive statistics were performed in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, 2018).

Statistical analysis

A multilevel logistic regression model was used to evaluate the association between colostrum quality (below or above and equal to 26.5%) and a series of explanatory variables. The explanatory variables tested were month of lambing, breed category (terminal/maternal/hill/unknown), age of the ewe, BCS, lambing environment, total number of lambs born, percentage of lambs born alive and stripping ease of the udder.

The model building was conducted in MLWiN version 3.04 (Rabash et al, 2001). Initial model building was performed by forward selection and explanatory variables were retained in the model where the estimated coefficient was greater than twice the standard error (such that the 95% confidence interval for the estimate did not include zero, equivalent to p<0.05); all rejected variables were reoffered to the final model and retained if they now met these criteria. The model used for analysis was a 2-level hierarchical model, in order to account for correlations between repeated samples within individual farms.

The model took the form:

Colostrum quality ≥ 26.5 % ( Yes=1, No=0 ) ~ Bernoulli ( π ij ) ( logit= π ) = α + β 1 X j + β 2 X ij + uj [ u j ] ~ N ( 0 , Ω u )

where subscripts i and j denoted the ith ewe of the jth farm, respectively. πij was the probability of the colostrum quality being ≥26.5% for the ith sampling point of the jth ewe, α the intercept value and Xij and Xj were explanatory covariates at sampling point and ewe levels respectively, with βn being the corresponding coefficients, uj was the random effect to account for residual variation between sheep (assumed to be normally distributed with mean = 0 and variance = Ωu).

Results

A total of 1295 samples were submitted from 64 farms in total, which represented 43.5% of the recruited farms. The median number of samples per farm was 20 (interquartile range 11–22). Forty three of the farms provided details of flock size, which varied from 60 to 2720 lambing ewes (median = 519 ewes). The median percentage of maiden ewes within the flock was 23% (range 0 to 41%). The majority of the lambings occurred in March 2021 (n=642) and indoors (n=1117), as highlighted in Table 1. There were 30 different breeds of ewe recorded (n=1241 ewes), which were categorised as terminal (n= 468), maternal (n=473), hill (n=294) or rare breed (n=6).

Table 1. The number of lambings occurring in the different lambing environments by month in 2020/2021

| Month of lambing | December 2020 | January 2021 | February 2021 | March 2021 | April 2021 | May 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of lambs | 11 | 32 | 134 | 642 | 351 | 6 |

| Number of indoor lambings | 11 | 32 | 133 | 581 | 247 | 2 |

| Number of outdoor lambings | 0 | 0 | 1 | 60 | 93 | 4 |

Quality of colostrum

For the purposes of this study, it was decided to use the Brix cut-off value of ≥26.5%, as proposed by Kessler et al (2021), as this is the only research to date, to the authors' knowledge, that determined the optimal Brix cut-off for colostrum samples with the recommended immunoglobulin concentration of 20 mg/ml immunoglobulin concentration of colostrum (Mellor and Murray, 1986; Nowak and Poindron, 2006; Alves et al, 2015). In this study, adequate colostrum quality refers to samples that have a Brix value of ≥26.5% (sensitivity 76.3%, specificity 87%, positive predictive value 95.1%, negative predictive value 52.6%) (Kessler et al, 2021).

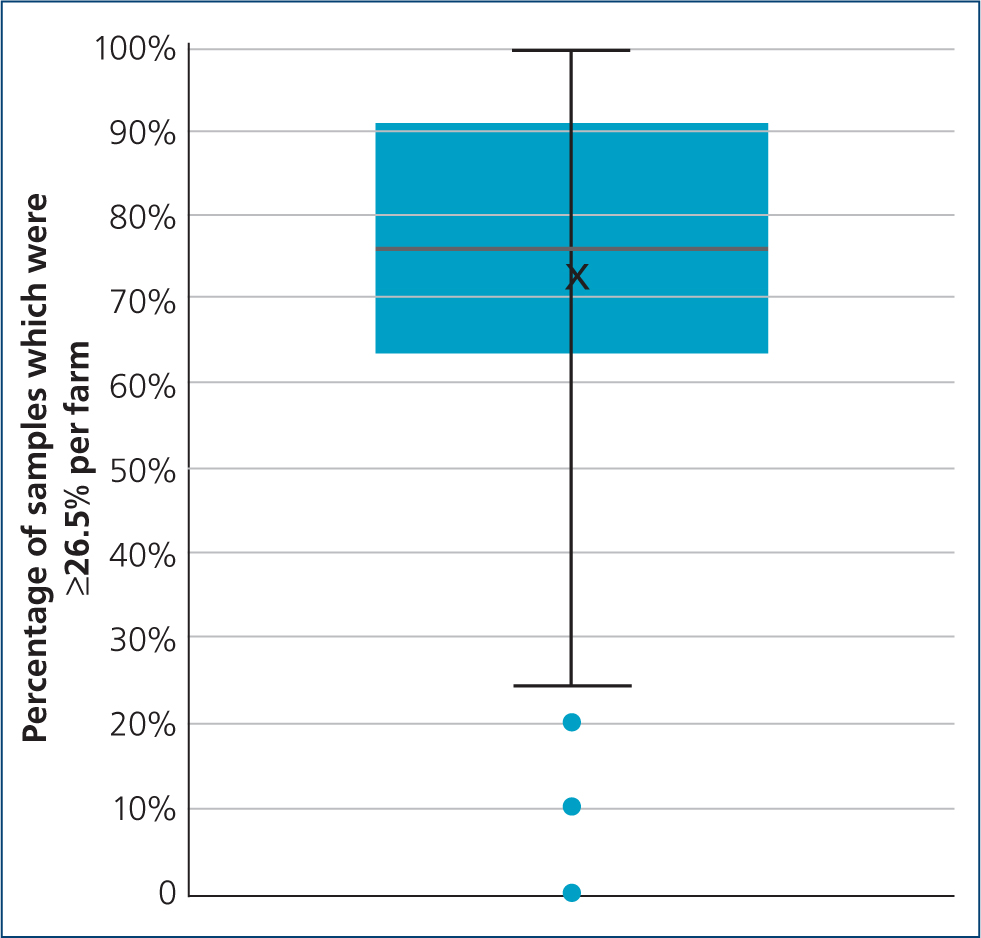

There were 1279 samples that had a quality recorded (98.8%), of which 74.8% had a Brix reading ≥26.5%. There were only nine farms for which all samples were ≥26.5% (14% of farm), with the median percentage of adequate quality samples per farm being 76.2% (mean: 74.3%) (Figure 1). Eight farms had less than 50% of the samples classified as adequate.

The majority of ewes were lambed indoors (n=1126) as 44 of the flocks were lambed solely indoors; only four of the flocks lambed solely outdoors (n=158 ewes). More than half of the ewes tested had twin lambs (57.3%, n=742), with 32.3%, 9.8% and 0.5% having single, triplet and quadruplet lambs respectively. All of the lambs were born alive in 93.4% of the recorded lambings (n=1209), with lambs born dead in 2.2% of births and 4.4% with an unknown outcome (Table 2).

Table 2. The percentage of colostrum samples per variable which were above the quality cut off of ≥26.5% Brix for 1279 colostrum samples from 64 flocks

| Category | Total number | Number of samples ≥26.5% | Number of samples <26.5% | Percentage of samples ≥26.5% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lambing environment | Indoors | 1117 | 868 | 249 | 77.7 |

| Outdoors | 157 | 85 | 72 | 54.1 | |

| Unrecorded | 11 | 10 | 1 | 90.9 | |

| Month of lambing | December 2020 | 11 | 8 | 3 | 72.7 |

| January 2021 | 32 | 30 | 2 | 93.8 | |

| February 2021 | 133 | 106 | 27 | 79.7 | |

| March 2021 | 636 | 485 | 151 | 76.3 | |

| April 2021 | 350 | 247 | 103 | 70.6 | |

| May 2021 | 6 | 5 | 1 | 83.3 | |

| Unrecorded | 117 | 82 | 35 | 70.1 | |

| Breed of ewe category | Terminal | 466 | 352 | 114 | 75.5 |

| Maternal | 467 | 333 | 134 | 71.3 | |

| Hill | 289 | 229 | 60 | 79.2 | |

| Rare | 6 | 5 | 1 | 83.3 | |

| Unrecorded | 41 | 38 | 3 | 92.7 | |

| Body condition score | ≤2 | 172 | 118 | 54 | 68.6 |

| 2.5 | 247 | 180 | 67 | 72.9 | |

| 3 | 431 | 330 | 101 | 76.6 | |

| 3.5 | 171 | 122 | 49 | 71.3 | |

| ≥4 | 116 | 95 | 21 | 81.9 | |

| Age of ewe (years) | Unrecorded | 148 | 118 | 30 | 79.7 |

| 1 | 124 | 95 | 29 | 76.6 | |

| 2 | 247 | 193 | 54 | 78.1 | |

| 3 | 238 | 176 | 62 | 73.9 | |

| 4 | 273 | 212 | 61 | 77.7 | |

| ≥5 | 270 | 183 | 87 | 67.8 | |

| Unrecorded | 133 | 104 | 29 | 78.2 | |

| Total number of lambs | Singles | 434 | 286 | 148 | 65.9 |

| Twins | 736 | 594 | 142 | 80.7 | |

| Triplets | 124 | 94 | 30 | 75.8 | |

| Quadruplets | 6 | 5 | 1 | 83.3 | |

| Unrecorded | 2 | 1 | 1 | 50.0 | |

| Percentage of lambs born alive (%) | 100 | 1200 | 905 | 295 | 75.4 |

| <100 | 83 | 57 | 26 | 68.7 | |

| Unrecorded | 2 | 1 | 1 | 50.0 | |

| Stripping ease | Good | 898 | 710 | 188 | 79.1 |

| Average | 788 | 702 | 86 | 89.1 | |

| Hard | 87 | 42 | 45 | 48.3 | |

| Unrecorded | 12 | 9 | 3 | 75.0 | |

| Colostrum colour | Yellow | 525 | 455 | 70 | 86.7 |

| Cream | 442 | 279 | 163 | 63.1 | |

| Yellow/cream | 210 | 199 | 11 | 94.8 | |

| White | 61 | 10 | 51 | 16.4 | |

| Yellow/white | 16 | 9 | 7 | 56.3 | |

| Unrecorded | 28 | 11 | 17 | 39.3 | |

The descriptions of the udder palpation were recorded in 1269 ewes, with 70.2% of udders being recorded as average or normal (n=891). Only a small minority of the udders had descriptors indicating potential mastitis (4.2%, n=53). In terms of the size of the udder, 9.1% were described as small (n=115) and 10.5% as large (n=133). The potential fill of the udder was not often used as a descriptor by farmers, with only 1.7% describing the udder as full (n=22) and 2.8% describing the udder as empty (n=11) or flabby (n=25). The stripping ease was found to be good in most cases (70.1%, n=898), with average and harder stripping ease found in only 22.6% (n=289) and 7.3% (n=94). A variety of different colostrum colours were described, with the majority of colostrum recorded as either yellow (40.8%) or cream (34.5%).

Impact of the pre-lambing nutrition

Pre-lambing nutrition information was available from 30 of the 64 original farms (47%), which included 560 colostrum samples. Out of the 560 colostrum samples, 424 were of adequate colostrum quality (76%). All of the flocks lambed indoors, with 27 of the flocks receiving silage as the main forage (90% of flocks, 496 colostrum samples).

Greater concentrate feed space per ewe was associated with better colostrum quality, with only 68% of samples of adequate quality when the space was less than the recommended 45 cm, and 84% adequate when the space exceeded the recommendation (Table 3). Supplementation of single bearing ewes was not associated with better colostrum quality, although supplementation of twin and triplet-bearing ewes was associated with improved colostrum quality.

Table 3. The percentage of colostrum samples per variable regarding supplementary feeding of ewes with concentrates for 30 indoor lambing flocks (n=560 colostrum samples)

| Variable | Total number | Number of samples ≥26.5% | Number of samples <26.5% | Percentage of samples ≥26.5% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentrate feed space per ewe | <45 cm | 167 | 114 | 53 | 68 |

| ≥45 cm | 174 | 147 | 27 | 84 | |

| Missing | 219 | 163 | 56 | 74 | |

| Supplementation of singles | No | 151 | 113 | 38 | 75 |

| Yes | 409 | 311 | 98 | 76 | |

| Supplementation of twins | No | 51 | 31 | 20 | 61 |

| Yes | 509 | 393 | 116 | 77 | |

| Supplementation of triplets | No | 31 | 16 | 15 | 52 |

| Yes | 529 | 408 | 121 | 77 | |

Forage feed space and silage metabolisable energy levels were not apparently associated with colostrum quality, but silage crude protein above 120 g/kg appeared to be associated with higher quality colostrum with 85% of samples above 26.5% on the Brix compared with 68% when the silage crude protein was lower than 120 g/kg (Table 4).

Table 4. The percentage of colostrum samples per variable regarding forage feeding of ewes with concentrates for 30 indoor lambing flocks (n=560 colostrum samples)

| Variable | Total number | Number of samples ≥26.5% | Number of samples <26.5% | Percentage of samples ≥26.5% | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Forage feed space per ewe | <15 cm | 116 | 89 | 27 | 77 |

| ≥15 cm | 249 | 184 | 65 | 74 | |

| Missing | 195 | 151 | 44 | 77 | |

| Main forage fed to ewes | Grass silage <10.5 MJ/kg | 289 | 227 | 62 | 79 |

| Grass silage ≥10.5 MJ/kg | 207 | 149 | 58 | 72 | |

| Hay | 64 | 48 | 16 | 75 | |

| Silage crude protein content | <120 | 177 | 120 | 57 | 68 |

| ≥120 | 269 | 229 | 40 | 85 | |

| Missing | 114 | 75 | 39 | 66 | |

| Silage D value (%) | <65 | 269 | 209 | 60 | 78 |

| ≥65 | 220 | 162 | 58 | 74 | |

| Missing | 71 | 53 | 18 | 75 | |

Despite 47% of the farmers returning diet information, the data were not considered detailed enough to perform any further statistical analysis, and thus the true significant of these results cannot be determined.

Statistical modelling: the impact of different variables on the quality of colostrum

The results of the final model are shown in Table 5. The odds of a colostrum sample containing adequate amounts of IgG (≥26.5% Brix) were significantly associated with stripping ease, with an increased odds of inadequate colostrum quality if the colostrum was difficult to strip from the udder (OR: 0.56). There was also a significant relationship with 5-year-old ewes having a decreased odds of adequate quality colostrum. There was a large amount of variation within the model, which was attributed to variation between flocks, rather than between ewes.

Table 5. Parameter estimates from the final multilevel logistic regression model with the binary outcome variable being whether a colostrum sample had a Brix refractometer reading ≥26.5%, based on 1279 colostrum samples from 64 flocks

| Model Term | Number | Odds Ratio | 95% confidence interval | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 2 | 124 | Reference | ||

| 3 | 255 | 0.90 | 0.51 to 1.60 | N/S | |

| 4 | 242 | 0.86 | 0.49 to 1.52 | N/S | |

| 5 | 264 | 0.53 | 0.31 to 0.93 | P<0.05 | |

| ≥6 | 262 | 0.84 | 0.47 to 1.47 | N/S | |

| Missing | 132 | 0.82 | 0.40 to 1.66 | N/S | |

| Stripping ease of the udder | Good | 894 | Reference | N/S | |

| Average | 287 | 0.79 | 0.57 to 1.09 | N/S | |

| Poor | 86 | 0.56 | 0.34 to 0.91 | P<0.05 | |

| Missing | 12 | 0.77 | 0.19 to 3.06 | N/S | |

Discussion

These results highlight that measurement of ewe colostrum with a Brix refractometer is useful as a management tool on commercial farms. There is continued debate as to an appropriate Brix cut-off with relatively few studies to date (Torres-Rovira et al, 2017; Agenbag et al, 2021). The cut off of 26.% was used in this study, as it was reported to have the highest sensitivity and negative predictive value (Kessler et al, 2021), which are the desired characteristics in this situation in terms of ensuring sufficient quality colostrum is received by the lamb.

Our results concur with a study reporting the 23% of ewe samples to be inadequate (Kessler, 2021), but differ from a study in Spain, in which approximately 62.7% of the samples were ≥18% Brix (cut off used in this study) and approximately 15% were ≥26.5% Brix, in 536 intensively housed dairy sheep (Torres-Rovira et al, 2017). There was large variation between farms with 14% of farms (n=9) having good colostrum quality (>26.5%) in all tested samples, while 14.0% of farms (n=9) had lower quality colostrum (<26.5%) in more than 50% of their tested samples (Figure 1).

The impact of flock level management decisions on colostrum quality was shown to have the largest impact on colostrum quality, as indicated by the unexplained variation in the model, which included mostly individual ewe potential risk factors. One of the largest between-farm management variations prior to lambing is pre-lambing nutrition. Good nutrition in late pregnancy has been shown to influence the synthesis of colostrum both through the provision of required nutrients and in the metabolism of progester-one (Mellor and Murray, 1986; Banchero et al, 2015).

The flock nutrition data indicated that ewes carrying multiple fetuses that received supplements tended to have higher quality colostrum samples (Table 4). This most likely reflects the fact that concentrate supplementation is designed to increase both energy and protein content of the diet. As the diet fermentable energy content increases in balance with rumeninal degradable protein, both dry matter intake and rumen function are optimised (Povey et al, 2016). Colostrum yield has previously been shown to be significantly reduced in Scottish Blackface ewes given a restricted diet in the last 45 days of pregnancy (Mellor and Murray, 1986), and the supply of glucose precursors via high energy grains such as maize, barley or wheat has been shown to enhance the production of good quality colostrum (Banchero et al, 2015).

Forage appeared to have impact in terms of the crude protein level, while the energy content and D-value of the forage appeared to have less of an impact on colostrum quality. Low levels of protein fed in late pregnancy have been shown to reduce the utilisation of starch (Banchero et al, 2015). The fact that D value appeared to have no impact was probably masked by the level of supplement supplied, with the whole diet being improved by additional fermentable energy and protein supplied in the concentrate.

The main significant risk factor at an individual ewe level was the reported stripping ease of the udder, with harder to strip udders having decreased odds of adequate colostrum, compared with those that were easier to strip (OR 0.56). This indicates that there may have been an issue with clinical or subclinical intramammary infection, as previously associated with a considerable reduction in lamb serum immunoglobulin concentration (Christley et al, 2003), or this could indicate that the lambs had suckled the colostrum prior to sample collection.

There did appear to be some difference in colostrum quality based on both litter size and ewe age, although these findings may have been confounded by flock level factors. Reviews of small ruminant colostrogenesis suggested that colostrum quality and quantity may be influenced more by ewe breed than by litter size or ewe age, although there have been limited studies in this area (Castro et al, 2011), and breed was found to be a non-significant factor within this study. This may also reflect differences in terms of the yield of colostrum produced, related to either age or breed of the ewe, as well as individual variation and flock management factors. Only 65.9% of the 434 single ewes sampled, had adequate colostrum quality, compared with 80.7% of the twin-bearing ewes (Table 2). Other studies have shown that twin bearing ewes often have higher levels of protein and fat, but lower levels of lactose than single-bearing ewes, although IgG levels are apparently not affected by litter size (Kessler, 2019). A high correlation between IgG and protein level and between Brix readings and total solids, including protein, has been reported, although only a moderate correlation has been reported between Brix and fat content. It is not possible to say whether the apparently lower quality of colostrum in the singles in this study was a result of flock level factors such as pre-lambing nutrition. There was also potential for bias with this result, as the study protocol specifically suggested that the farmers should sample ewes with multiple lambs. There may have been bias introduced in that farmers may have additionally chosen to sample single ewes that were of concern.

While the study has highlighted the prevalence of inadequate colostrum samples, there were some limitations to this study. First, the study only investigated colostrum quality on sheep farms in Wales, which may have a risk of the systems analysed not reflecting all UK sheep farming systems. However, with 64 respondents, with varying breeds and lambing practices, it is highly likely that this study does reflect UK sheep farming practices. It also relied on farmers taking samples from sheep in a non-biased manner and accurately measuring and recording the results, as well as other factors regarding the dam. This was a considerable demand from farmers during a busy period and may have led to an element of subconscious bias, as well as a desire to outperform the rest of the group. The study considered colostrum quality but did not consider the other two important elements of colostrum management — namely colostrum quantity and how quickly or effectively the colostrum reached the lambs. There are also multiple other factors, which have been reported within the ruminant literature impacting colostrum quality, including the time of collection post partum, the cleanliness of the sample and volume of colostrum produced (Godden, 2008; Haggerty et al, 2021); however these factors were not accounted for and their impact is unknown.

Some of the factors measured in this study are subjective, such as stripping ease, BCS and udder palpation, and were performed by multiple people across the study and possibly within a single farm, making the results less reliable. The lack of clarity and complexity of the pre-lambing nutrition from the farm survey and lack of responses, indicates that this is an area that is hard to analyse robustly in this type of study and requires further research in the form of a randomised control trial.

Despite the limitations of this study, it has highlighted a simple method to engage commercial sheep farmers with measuring colostrum quality of individual ewes in both indoor and outdoor lambing flocks. The majority of ewes tested in this study had high quality colostrum which should reassure sheep farmers as they are encouraged to optimise colostrum management and avoid unnecessary antibiotic use in neonatal lambs.

It has shown a range of colostrum quality and suggested both ewe-level and flock-level factors that influence this with the most significant drivers at a flock level, and most likely related to the prelambing nutrition. Further work needs to be undertaken to consider passive transfer and whether further simple techniques can better ensure good immunoglobulin levels in lambs.

Conclusion

This study has shown that that 76% of samples were considered to be good quality, across a wide range of flocks and using the Brix cut off of 26.5%. The main drivers for determining the quality of colostrum were found to be at the flock level, with the pre-lambing nutrition playing a potentially large role. The impact of supplementary concentrate and trough access, as well as silage crude protein have potential roles in determining colostrum quality and require further research. The study also highlighted the ease at which farmers can monitor the colostrum quality in their flock, with aim of improving neonatal lamb health and performance.

KEY POINTS

- Colostrum quality was considered to be inadequate in 25.2% of samples submitted.

- All colostrum samples from 14% of the farms were considered below the ideal threshold for good quality (>-26.5% Brix reading).

- Better colostrum quality was related to feeding management with greater trough space (at or above the recommended space) for concentrate feeding correlated with higher Brix readings.

- Silage crude protein above 120 g/kg dry matter was associated with better colostrum quality suggesting the importance of balancing diets correctly to provide adequate protein to ewes in late pregnancy, with consequent implications for silage making (fertiliser use, sward constituents (clover etc) and cutting dates).

- There appears to be significant scope to improve colostrum management, and potentially lamb survival on many farms through improved feeding management and nutrition.

- The Brix refractometer encouraged farmers in this study to focus on colostrum management and wider use should be promoted.