Downer cows, defined as bright, alert and responsive cows that have been recumbent for at least 1 day, are challenging for many veterinarians (Eddy, 2004). They can be difficult to examine and the associations between the primary cause of the recumbency, the secondary damage as a result of their recumbency, the conditions under which they have been cared for and their outcome are oft en poorly understood.

The term downer cow syndrome was originally coined to describe persistently recumbent cows, usually following hypocalcaemia (milk fever). Over the years it was associated with many conditions (Kronfeld, 1970), but Cox et al (1982) showed ‘ischaemic necrosis of the caudal thigh muscles, inflammation of the sciatic nerve caudal to the proximal end of the femur’ and ‘evidence of peroneal damage’ in cows where downer cow syndrome was experimentally induced by maintaining sternal recumbency in healthy cows for up to 12 hours using halothane anaesethia. Their model of pressure-induced damage to the hind limbs became the accepted explanation for downer cow syndrome. This concept was further explained by Malmo et al (2010), who described downer cow syndrome as ‘associated with the pathology that develops secondarily to prolonged recumbency’. They listed hind limb muscle and nerve damage, radial nerve damage, coxofemoral dislocation, fracture of the femoral neck, and further skeletal injury, such as haemorrhage in or rupture of the adductor or gastrocnemius muscles as likely secondary damage in downer cows (Malmo et al, 2010).

Guidelines for the nursing of down cows are oft en fairly general and many veterinarians rely on experience gained during their clinical work (Eddy, 2004; Huxley et al, 2010). Huxley et al (2010) listed the provision of accessible feed and water, regular turning and lift ing, and deep, soft bedding with good footing as the three most important factors of nursing care.

Cows can become recumbent from a wide range of possible causes and the primary cause of their recumbency must be adequately addressed. Secondary damage is known to be a factor in those that are persistently recumbent and this damage must also be taken into consideration. There is an inter-play between the primary cause of, and the secondary damage resulting from, the recumbency. Some cows will only be affected by the primary cause, some will remain recumbent solely from the secondary damage, and some cows will have both primary and secondary factors. There is little work in the current literature documenting this relationship. Similarly, the quantitative effect of the level of nursing care on outcome is also lacking in the literature.

Downer cow management is an important animal welfare consideration for the individual animal and it is also important from the cattle industry's perspective in the current climate of consumer scrutiny. Farmers and veterinarians must ensure that downer cows are treated and cared for appropriately or euthanased in a timely manner. This requires a thorough understanding of the pathogenesis of downer cow syndrome.

The hypothesis for this study was that for most downer cows the secondary damage following recumbency is more important that the primary cause of the recumbency, and that the level of nursing care provided to downer cows is a major determinant of outcome.

Case history

The researcher veterinarian (author) investigated multiple downer cow cases in dairy cows under commercial farming operations in South Gippsland, Australia during two 3-month seasonal calving periods in 2011 and 2012. A downer cow was defined as a bright and alert dairy cow that had been recumbent for more than 1 day. This study was initiated by Dairy Australia to investigate the management of downer cows on commercial dairy farms.

Farmers with cows recumbent from calving paralysis were allowed to contact the researcher directly, but all other cases needed to be attended by local veterinarians initially with suitable cases referred to the researcher. A complete history was obtained from the farmer and referring veterinarian, where applicable, to determine the likely cause of the initial recumbency and to help differentiate between primary and secondary damage. Cows were excluded from the study if this information was vague.

Secondary damage was defined as findings that were not consistent with the likely cause of the original recumbency and damage found at subsequent veterinary examination that was not present previously.

The primary researcher conducted a thorough clinical, medical and musculo-skeletal examination on each cow at each visit. Blood samples for minerals, such as calcium, magnesium and phosphorus were not collected. The musculo-skeletal examination included:

- Assessment of the spinal column for fractures

- Assessment of the limbs for damage to joints, tendons, ligaments and muscles

- Nerve function assessment by:

- Flexor-withdrawal reflex, patellar reflex and muscle tone assessment in the recumbent position

- Observation of postural responses when they tried to stand and/or when they were lifted, usually with a hip clamp, including using chest straps for cows that failed to bear weight on the fore limbs when lifted

- Flexor-withdrawal reflex and muscle tone assessment were repeated in the elevated position

- Blood samples were usually taken for serum analysis of creatinine phosphokinase (CK) after the cow had been down for more than 1 day unless the cow could walk after being lifted

Musculo-skeletal abnormalities and medical conditions were diagnosed using standard methods but the diagnoses of some specific musculo-skeletal conditions are listed below:

- Sacro-iliac damage was diagnosed by an increased laxity of the sacro-iliac joint when subjected to motion palpation

- Sciatic nerve dysfunction was indicated by a number of symptoms, depending on which branches of the nerve were involved — increased patellar reflex, decreased sensations of the caudal and/or anterior pastern, proprioceptive defects, and/or a tendency for an anterior or anterior-medial displacement of the leg when lifted

- Femoral nerve dysfunction was indicated by decreased or absent patellar reflex and a tendency for a caudal displacement of the hind limbs when trying to stand

- Brachial plexus paralysis was indicated by flaccid paralysis and negative flexor-withdrawal reflex of the fore limb, which was assessed in both the prone and raised positions

- Radial nerve paralysis was indicated by flaccid lower fore limb function and a proprioceptive deficit when lifted but normal upper limb function

- Tibial paresis was diagnosed by hyper-extension of the stifle, mild over-flexion of the hock, and a slightly flexed fetlock but with the claw in a normal position when the cow was lifted

- Compartment syndrome was diagnosed when CK levels were above the time adjusted threshold levels of 50, 44 or 38 times the upper normal CK level (250 U/L Veterinary Clinical Pathology, University of Melbourne), which represented values of 12 500, 11 000 and 9500 U/L for cows recumbent for 1, 2 or 3 days, respectively. Muscle enzyme values above these thresholds indicated a less than 5% chance of recovery (Clark et al, 1987).

‘Clinically important’ secondary damage was defined as secondary damage that ‘can cause recumbency in its own right, or delay or prevent recovery from the primary cause of the recumbency’.

The cows were revisited where possible, often multiple times, and re-examined to chart their progress and record any further secondary damage. The conditions under which the cows were cared for were recorded by the researcher based on his observations and detailed questioning of farmers, and were compared with ‘gold standard’ nursing conditions, as shown in Table 1 (Poulton et al, 2016b). ‘Satisfactory’ nursing was defined to be greater than 50% compliance to ‘gold standard’ nursing and ‘unsatisfactory’ nursing was defined as less than 50% compliance. This judgement was made retrospectively by the researcher and averaged over the recumbency period after allowing for changes in conditions during the time. For those cows that did not recover a judgement was made by the researcher as to whether the reason for their non-recovery was due to their primary affliction, secondary damage or a combination of primary and secondary damage. The relationships between the occurrence of secondary damage, outcome and the standard of nursing care were analysed.

Table 1. Optimum standard of nursing care for southern Victorian dairying areasa

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| Treatment | Appropriately treated for the primary cause of the recumbency |

| Appropriately treated for any secondary conditions following the recumbency | |

| Location | For recumbent cows:

|

| Bedding | Cared for on deep, soft bedding of suitable material:

|

| Weather conditions | Protected from adverse weather conditions including excessive cold and heat |

| Barriers | For recumbent cows:

|

For cows that can stand after being lifted but unable to walk:

|

|

| Rolling | For cows that are unable to swap sides by themselves:

|

| Lifting | Cow only lifted if:

|

| Hygiene | Clean and dry conditions are provided |

| Area is regularly cleaned to prevent build-up of manure, urine and moisture | |

| Level of care | High levels of ‘tender love and care’ provided at all times |

| Adequate levels of labour provided | |

| Feed and water | Access to good quality feed at all times |

| Adequate provision of suitable drinking water | |

| Udder care | Milking is optional unless leaking milk |

| Teat disinfection twice daily | |

| Moving between location | Moved in a way to avoid inflicting further damage, such as by:

|

From Poulton et al 2016b

Clinical findings

218 downer cow cases were investigated on 96 commercial dairy farms. The primary causes of their recumbencies were: calving paralysis 98 (45 %) cows, back injury 41 (19%) cows, milk fever 37 (17%) cows, protein-energy deficiency (pregnancy toxaemia) 30 (14 %) cows, ‘other’ 12 (5%) cows. By day 7, 52 (24%) cows had recovered and 69 (32%) cows eventually recovered. Of the 149 cows that did not recover 131 cows were euthanased and 18 cows died.

The researcher examined 105 (48%) cows on the first day of their recumbency, 57 (26%) cows on the second day, 34 (16%) cows on the third day, 10 (5%) cows on the fourth day and 12 (6%) cows had been down for more than 4 days when first attended by the researcher. 48 (22%) cows were only examined once by the researcher. 91 (42%) cows were revisited by the researcher once, 51 (23%) cows twice, 18 (8%) cows three times, 6 (3%) cows four times, 1 (0.5%) cow five times, 1 (0.5%) cow six times, 1 (0.5%) cow seven times and 1 (0.5%) cow was revisited eight times.

Some type of secondary damage was recorded in 183 (84%) cows and 101 cows had more than one type of secondary damage. ‘Clinically important’ secondary damage occurred in 173 (79%) cows. The list of secondary damage that was recorded is shown in Table 2. 32/45 (71%) cows without ‘clinically important’ secondary damage eventually recovered compared with 37/173 (21%) cows with ‘clinically important’ secondary damage (RR=3.33; 95% CI 2.36-4.68).

Table 2. Types of ‘clinically important’ secondary damage recorded in 218 downer cowsa

| Group | Specific type of damage | Nb | % of cowsb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Forelimb neuropathies | Brachial plexus paralysis | 23 | 10.6 |

| Radial nerve paralysis | 15 | 6.9 | |

| Hind limb neuropathies | Femoral nerve damage | 50 | 22.9 |

| Sciatic nerve damage | 25 | 11.5 | |

| Tibial paresis | 16 | 7.3 | |

| Structural | Hip dislocation | 30 | 13.8 |

| Sacro-iliac damage | 4 | 1.8 | |

| Back fracture | 3 | 1.4 | |

| Adductor muscle/obturator nerve damage | 6 | 2.8 | |

| Gastrocnemius muscle damage | 10 | 4.6 | |

| Compartment syndromec | 61 | 30.0 | |

| Muscle atrophy | 21 | 9.6 | |

| Bed sores | 24 | 11.0 | |

| Joint infection | 7 | 3.2 | |

| Lifting damage | 15 | 6.9 | |

| Stifle ligament rupture | 1 | 0.5 | |

| Organ | Aspiration/choke | 10 | 4.6 |

| Pneumonia | 3 | 1.4 | |

| Exposure | 19 | 8.7 | |

| Mastitis | 4 | 1.8 | |

| Scours | 3 | 1.4 | |

| Other infection | 4 | 1.8 | |

| Heart failure | 1 | 0.5 | |

| Other | ‘Given up’ | 31 | 14.2 |

| Total | 386 |

Modified from Poulton et al 2016a

bMore than one type of damage was diagnosed in 101 cows

cCompartment syndrome diagnosed when creatinine phosphokinase (CK) levels were above the time adjusted critical level indicating <5% chance of recovery (Clark et al, 1987)

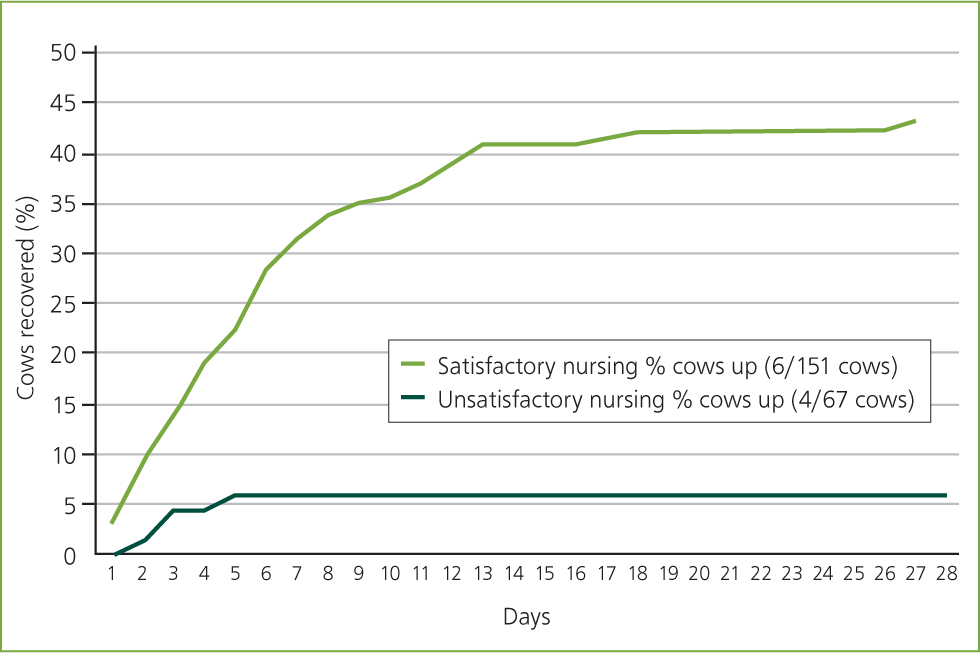

151 (69%) cows were deemed to have been nursed ‘satisfactorily’ and 67 (31%) nursed ‘unsatisfactorily’. ‘Clinically important’ secondary damage was found in 61/67 (91%) cows nursed ‘unsatisfactorily’ compared with 112/151 (74%) cows nursed ‘satisfactorily’ (RR=1.23; 95% CI 1.09-1.38). Recovery by day 7 for the cows nursed ‘satisfactorily’ was 48/151 (32%) compared with 4/67 (6%) cows nursed ‘unsatisfactorily’ (RR=5.32; 95% CI 2.00=14.17). Eventual recovery for the cows nursed ‘satisfactorily’ was 65/151 (43%) cows compared with 4/67 (6%) cows nursed ‘unsatisfactorily’ (RR=7.21; 95% CI 2.74=18.98).

Figure 1 shows the daily recovery of the cows nursed ‘satisfactorily’ and ‘unsatisfactorily’.

For the 149 cows that did not recover it was judged by the researcher that 20 (13%) cows were lost solely from the primary cause, 21 (14%) cows were lost from a combination of primary and secondary conditions and 108 (72%) cows were lost solely from secondary damage.

Discussion

Cows can become recumbent for a large variety of reasons and it is important that farmers and veterinarians correctly diagnose the initial cause of the recumbency to ensure the cows are treated appropriately. Once cows are recumbent, they are at risk of suffering secondary damage, some types of which can perpetuate the recumbency and delay or prevent recovery. The clinical presentation of a down cow can involve either primary pathology, secondary pathology or a combination of both primary and secondary pathology in any degree of relative importance.

In this study of 218 field cases of commercial dairy cows that had been recumbent for more than 1 day and were bright and alert it was found that in most cases the secondary damage was more important than the primary cause of the recumbency. It was also found that the level of nursing care provided was a major driver of outcome.

Of the 149 cows that did not recover it was judged by the researcher that nearly three-quarters of them did not recover solely from the secondary damage sustained after they became recumbent. While this does not negate the importance of the primary cause of the recumbency as the cow still needs to be correctly diagnosed and treated appropriately for the primary condition, it highlights the importance of secondary damage in determining outcome for downer cows.

‘Clinically important’ secondary damage was found to be very common affecting 79% of the cows. There was a wide range of types of clinically important secondary damage and many cows were affected by more than one type during their recumbency. The study adds to the current literature by documenting the range and occurrence of these conditions in over 200 clinical cases. Some types of secondary damage, such as femoral nerve and brachial plexus damage, were found to have higher occurrences than previously reported in the literature. ‘Clinically important’ secondary damage was found to have a highly significant influence on the chance of recovery of the downer cows. Farmers and veterinarians must be aware of this so they look for the various types that may occur, and supplement/change the treatment and management of the cow from the original protocols, as required. Continuing to treat a downer cow that originally became recumbent from milk fever with more metabolic solutions may be inappropriate if she continues to be recumbent from, say, secondary femoral nerve damage.

The study found that the conditions under which the cows were cared for while recumbent were highly significant in determining the cows' outcome and the occurrence of clinically important secondary damage. For a recumbent cow to recover she must heal from the primary cause of her recumbency, and either not suffer ‘clinically important’ secondary damage or recover from it, if it occurs. A high level of compliance to ‘gold standard’ nursing was found to positively influence outcome both directly, by increasing the chance of recovering from the primary cause, and indirectly, by decreasing the occurrence of ‘clinically important’ secondary damage and increasing the chance of recovering from any secondary damage that had occurred.

Veterinarians must actively engage in the supervision of the nursing conditions of recumbent cows to ensure the farmers are implementing high quality care. This can be an area less focused on by veterinarians as they may be more directed towards drug treatment. Data from this study showed the profound impact that high quality nursing had on outcome. It also showed that no cow being nursed ‘unsatisfactorily’ recovered after being recumbent for more than 5 days whereas cows nursed ‘satisfactorily’ continued to recover into the second, third and even fourth week of recumbency. When veterinarians are assessing the likely prognosis for a recumbent cow, along with the degree of damage affecting the cow they must factor in the level of care that the cow will receive. Any cow that cannot be nursed ‘satisfactorily’ should be euthanased after a few days if not recovered, as they are unlikely to recover.

Limitations of the study

The diagnoses made by the researcher were all based on his findings from clinical examinations under field conditions in association with detailed histories from the farmers and referring veterinarians, when applicable. Blood analysis was only conducted for muscle enzymes tests. While many cows had veterinary attention on the first day of their recumbency there was a delay of several days for some of the cows. Every effort was made to be as objective as possible when allocating primary cause to each cow and when determining what damage was primary and what was secondary, but it is possible that there may have been some errors especially as a few cows had been down for more than 4 days when first attended by the researcher. Assessment of nursing quality was based partly on information provided by the farmers, which may not have always been fully accurate. These factors may raise questions as to the validity of some of the data, but as the findings showed so overwhelmingly the importance of secondary damage and nursing quality on outcome it would not change the conclusions. The scenarios encountered by the researcher are common to field veterinarians, which makes the findings of the study valuable.

Conclusions

Findings from this study showed that for the majority of bright and alert cows that have been recumbent for more than 1 day secondary damage from recumbency was more important than the original cause of their recumbency. The study also showed a very strong association between nursing quality and outcome, such that any downer cow that is being cared for at an ‘unsatisfactory’ level should be euthanased after only a few days if not recovered. It is important that farmers and veterinarians understand these findings when managing downer cows to ensure appropriate animal welfare standards are practiced.

Ethics

The Faculty of Veterinary Science Animal Ethics Committee deemed that ethics approval was not required for this research, as the study involved observation of clinical cases of recumbent cows under normal field conditions. The examinations performed on the cows were considered to be normal veterinary procedures rather than experimental in nature.

KEY POINTS

- Recumbent cows are very susceptible to secondary damage.

- Within reason, secondary damage is more important than the original primary cause of the recumbency in most downer cows.

- The quality of nursing care provided to downer cows is highly influential in determining their fate.

- If high quality nursing care cannot be provided to downer cows, they should be euthanased after a few days as they are highly unlikely to recover.

- Downer cow management is an important animal welfare issue.