This cases series present real life cases from first opinion farm animal practice to illustrate some common dermatological presentations. Following the format of a case report, the background to the case, with consideration of history and signalment is presented, along with the approach to the case, including clinical examination and diagnostic work up. For each case a discussion of treatment options is presented and elements to be considered by way of herd level impact and preventative practices are included.

The itchy sheep

It is June in North Somerset and the NADIS (2023) forecast shows a high risk for period for myiasis. A client with a flock of 60 Poll Dorset ewes has called because one of the rams has a large area of wool loss. They describe signs of pruritus too. They are happy to put the ram in a trailer and bring him down to the practice for assessment. The ram was in a group with three other rams, none of which were showing similar signs currently.

On examination the ram is bright and alert, and he is standing comfortably. His heart rate, respiratory rate and temperature are within normal limits. He is in good condition with a body condition score of 4 out of 5. There is a large area of alopecia over the dorsum extending from mid-way up the neck to mid-way along the back and down both shoulders to the axilla (Figure 1). The skin in this area is erythematous, warm to the touch and there are multifocal areas of excoriation (Figure 2). No ectoparasites are visible including blowfly larvae.

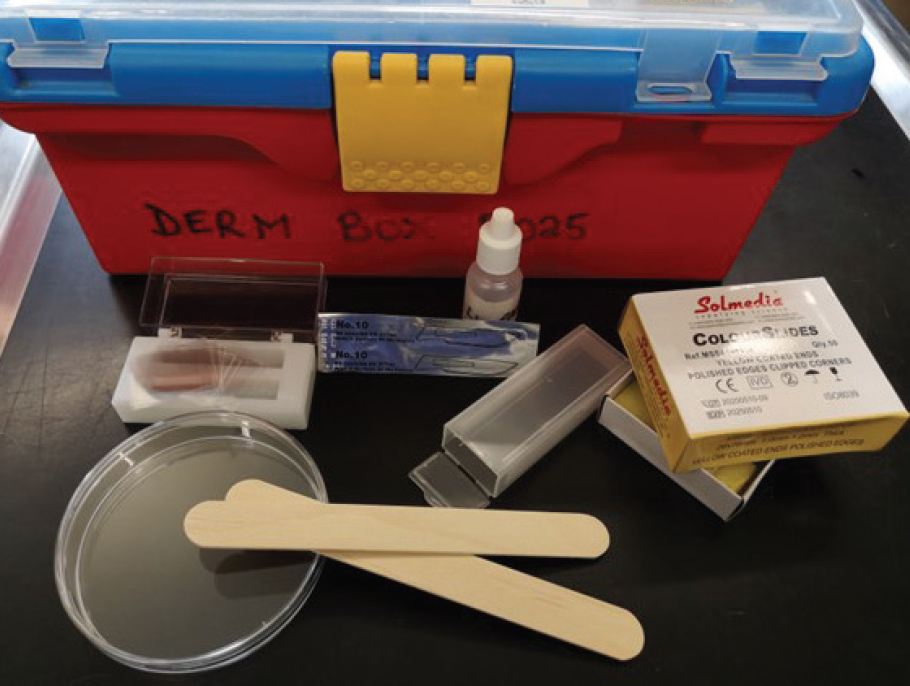

Ectoparasites were considered a likely cause in this case and based on the severity of pruritus, Psoroptes ovis, known commonly as ‘sheep scab’, was considered the most likely diagnosis. This disease is diagnosed using superficial skin scraping ideally taken from the margins of crusted lesions. Box 1 describes what to include in a dermatology box for examination of dermatological presentations in ambulatory practice. Biosecurity of associated equipment is of paramount importance when handling and collecting samples from these cases, particularly in ambulatory practice when moving farm to farm.

Box 1.What to include in a dermatology box for use in large animal ambulatory practice

- Microscope slides

- Liquid paraffin

- Cover slips

- Slide boxes

- Petri dishes/sterile sample pot (to collect skin scraping material)

- Acetate tape

- Scalpel blades (eg size 10)

- Tongue depressor (can be used for superficial skin scrapings if a scalpel blade is not practical)

- Pencil to label slides

- Plain and charcoal swabs

Blood testing for antibodies to P. ovis can also be performed. A positive result will confirm mites have been present; however, as antibodies will remain for weeks to months after infestation, this test cannot be used alone to diagnose a current outbreak (Ochs et al, 2001). Diagnosis of ‘sheep scab’ has significant implications and it is important to reach a definitive diagnosis when it is suspected. It remains a notifiable disease in Scotland and there is a legal obligation for treatment in England and Wales. Treatment can be challenging as it is costly and labour intensive for the client.

The most challenging aspect of treatment and control of this condition is the impact of reinfestation from the environment. The whole flock needs to be treated and follow up treatments may be required, depending on the approach taken. Injectable macrocytic lactones can be an effective treatment (Table 1) (SCOPS, 2023b); however, it should be noted that retreatment may be required for some products including those containing 1% moxidectin, ivermectin and doramectin (Table 1). Products containing 2% moxidectin provide treatment and prevention against reinfection for 60 days. This product is administered at the ear base, so some training in this technique may be required.

Table 1. Products suitable for scab control

| Chemical | Retreatment required | Retreatment interval |

|---|---|---|

| Ivermectin | Yes | 2 injections 7 days apart |

| Moxidectin (1% solution) | Yes | 2 injections 10 days apart |

| Moxidectin (2% solution) | No | |

| Doramectin | No |

‘Sustainable control of parasites in sheep’ (SCOPS) principles should be followed to ensure the treatment is effective and to avoid resistance issues; ensuring accurate weights are identified and treatment based on the heaviest in the group to avoid underdosing. Equipment should be checked for calibration to ensure the anticipated dose is delivered. The whole flock must be treated; it may be tempting to leave some seemingly unaffected animals untreated; however, as subclinical infestation occurs, this would be a common method of reinfestation and treatment failure. Eggs are not affected by the ectoparasiticides listed above and follow up treatments at 10 days are required when using short-acting products to ensure emerging mites are also treated. It should be acknowledged that the macrocyclic lactones will also have an effect on roundworms such as GI nematodes, so these treatments should be factored into the approach to worm control.

This flock had experienced issues with sheep scab earlier in the year and they had found two treatments with a macrocyclic lactone to be ineffective. Resistance to macrocyclic lactones has been reported, although it is also acknowledged that treatment failures are commonly due to issues with treatment application or management (Sturgess-Osborne et al, 2019). Plunge dips using organophosphate have been shown to be highly effective in sheep scab control. Control via dipping has been elected as the method of choice for a recently launched eradication plan in Wales (Gwaredu Scab, 2023). These products have to be used in a controlled manner due to their toxic nature, so would often involve a ‘mobile dipper’ with equipment and certification of competence, who should be following the ‘Code of Practice’ for use (SCOPS, 2023a). Cost implications may be of consideration for a small flock where the cost of dipping is likely to be higher per animal if the service is charged at a set fee by the contractor. The Veterinary Medicines Directorate (VMD) requires that application must be via dip rather than shower or spray to be effective. One benefit to this approach is the residual action that remains for several weeks after treatment.

Prevention of reinfestation is important to keep in mind when advising clients about the management of sheep scab. Psoroptes mites can survive off the host for up to 17 days, and animals should not be returned to the same environment where mites can be present, particularly where sheep have been scratching on fences, posts and hedges, for several weeks. Potential fomites for harbouring of mites and reinfestation must be identified; for example any equipment used when handling for treatment needs to be thoroughly cleaned.

The flock elected to treat again with 2 doses of moxidectin. SCOPS principles were discussed again in the hope of a better treatment outcome this time. Treatment appeared to be successful with no further cases of scab identified in the following months.

The flaky cow

A 200-cow dairy herd has cows housed all year round. The shed is purpose built with concrete panels to head height and Yorkshire board to the eaves. Cubicles have a deep sand bed and metal cantilever divides. Automatic scrapers clean the passageways. The milking herd is split in two and grouped by high and low yielding cows. There is a central passageway and feed face where a total mixed ration is fed. Water troughs are located at either end of the shed and automatic cow brushes are also situated in loafing areas, one for each group of cows. Udders are ‘flamed’ to remove hair and cow tails are clipped to promote cleanliness of the udder at milking and to avoid entrapment of tails in the brushes or scrapers.

During a routine fertility visit, while performing rectal examinations, it is notable that many of the cows have areas of alopecia, scaling and excoriation around the tail head (Figures 3 and 4). The farmer comments that the brush for the high yielding group had broken and they assumed the increase in scale evident around the tail head was just a sign that they hadn't been able to use the brushes. The farmer hasn't noticed signs of pruritus; however, without access to the brush it is hard for the cows to display pruritic behaviours. On closer examination, some cows do appear pruritic when the area is examined, lifting the tail head and responding to palpation of the area either side of the tail head. The signs are confined to this area of the body.

Following discussion around potential causes of the signs the farmer agrees to diagnostic testing and skin scrapes are taken. Differentials for this presentation vary in their significance. Chorioptes bovis would be the most likely diagnosis given the area affected and clinical signs seen. These mites can cause pruritus although clinical signs are typically mild. Psoroptes mites cause intense pruritus such that production losses may be seen and, although they are less likely in this case, remain an important differential to investigate, as prompt and effective treatment is required to limit the economical impact. Housed animals are prone to lice but a more diffuse presentation would be expected with pediculosis across the flank.

Examination of superficial skin scrapings confirms the presence of Chorioptes. When formulating a treatment plan for dairy cows, consideration of milk withdrawals and the associated economic impact is important along with the route of administration when herd level treatments are to be instigated. There are effective products which can be used in ‘pour on’ formulations, and with a 0 day milk withdrawal, such as eprinomectin; however, the cost of this to a herd can be high and treatment decisions will be balanced against the impact of the condition. In this case the farmer treated the high yielding cows and infection did appear to be limited to this group. Clinical signs had improved in the majority of cows by the next routine fertility visit.

The stamping alpaca

A local small holder has a breeding herd of alpacas. They have 15 breeding females that birth yearly, they sell some offspring as well as some breeding females, and buy in new stud males from time to time, as well as sending some dams off site for breeding purposes. They are aware of the risk of introduction of issues as stock moves on and off the holding and quarantine animals in a shed for a week on arrival or return to their holding.

They have called for examination of a new stud male who they have recently purchased from another breeder. There was no history of concerns reported by the seller but they have noticed the male stamps his feet frequently when at rest and they are suspicious that this is a sign of some discomfort.

On examination of the alpaca there is extensive hyperkeratosis extending from the fetlock and around the accessory digits up to the axilla. Otherwise he is clinically well, with temperature, pulse and respiratory rates within normal ranges, and no abnormalities of the gastrointestinal tract on examination. Chorioptic mange in alpacas can occur with or without clinical signs of disease. Pruritus is usually mild, and other common signs include alopecia and scaling of the tail base and ventral abdomen (Foster et al, 2007). The marked hyperkeratosis present in this case can be a clinical sign of sarcoptic mange, idiopathic hyperkeratosis syndrome or chronic chorioptic mange. It was suspicious from the history of the previous holding that chronic chorioptic mange was possible, and microscopy of skin scrapings confirmed presence of this mite. In such cases, superficial skin scrapes should be performed. Best results will come from a superficial skin scrape at the margins of the lesion. Skin scrapings from the axilla and interdigital space are the most commonly found positive. In contact animals can also be sampled to increase chances of confirming mite presence.

When starting treatment, owners need to be aware that a prolonged course of management is going to required. Macrocyclic lactones can be effective in treating the mites and ivermectin is administered subcutaneously at a dose of 0.4–0.6 mg/kg (Foster et al, 2007; VetPartners, 2023). Note this is a higher dose than that used in other species and repeated treatments are often required, eg at 7–14 day intervals in some cases for months. However, often treatment can substantially reduce mite numbers but is not able to eliminate them and eradication of Chorioptes from a herd is challenging. Pour on ivermectins formulated for other farm species do not appear to work and this is in part due to the difference between alpaca fibre and fleece of other farm species with a higher lanolin content (Foster et al, 2007). Bathing with a keratinolytic shampoo is also recommended to support resolution of clinical signs.

Alpacas that have shown extensive signs are at risk from recurrence of signs if the mites return to the herd. With a herd with much animal movement this is likely, so vigilance is important.

The poor doing nanny

A 4-year-old nanny is presented as ‘quiet’ and with a recent decline in condition. The nanny is part of a small herd in a small holding, including her offspring from a year ago, one other nanny and four sheep. There has been little ongoing work with this client, no health plan is in place and the last communication was a dispense of clostridial vaccines 6 months ago.

On examination the nanny is very quiet, she is standing but reluctant to move. She has an increased respiratory rate and effort and increased heart rate. Her temperature is normal and there are normal rumen turnovers and rumen fill is as expected. She has a full mouth, no missing dentition and no palpable lymphadenomegaly. Her mucus membrane colour was very pale. Her coat was dull in appearance and ectoparasites were also visible. Identification of the ectoparasites was possible on visual examination due to their size and they were identified as lice. Goats can be affected by sucking lice – Linognathus stenopsis, and chewing lice – Bovicola caprae. In this case, the pale mucus membranes were an indication of anaemia, confirmed by bloods collected and run in the practice laboratory for assessment of packed cell volume (PCV). The presence of anaemia was suggestive of pediculosis with sucking lice.

Treatment was focused on the ectoparasites and blood transfusion was not elected in this case but should be a consideration based on the PCV. Injectable ivermectin is effective in treating sucking lice and although not licensed for this species, can be used on the cascade at a dose rate of 200 µg/kg (Matthews, 2016). The owner was advised on supportive care for symptomatic treatment. The goat was kept housed with easy access to water, forage and the addition of some concentrate feed. Following treatment for the ectoparasites the clinical signs improved, primarily evidenced by an improved demeanour. She was not re-presented for follow up of the anaemia but the improved demeanour would suggest this was no longer an issue once the ectoparasites were controlled.

In this case it was not clear how the ectoparasites had entered the herd, and why this animal in particular was affected. Treatment of the others in the flock with ‘spot-on’ deltamethrin was advised to prevent reinfestation (2016). No animal movement had occurred on or off the holding. It is possible that contact with wildlife may have been the route of infection.

Conclusions

Dermatological presentations are common in farm animals. Not all cases will reach a clinician for examination so having an awareness of common differentials, the associated clinical signs and diagnostic approach is essential to triage cases, whether that be client queries by phone or images. To promote prompt and effective treatment it is important to reach a definitive diagnosis, and this can be achieved with knowledge of sampling techniques that are easily applicable in practice. Our approach to treatment must be mindful of the fact that many of the products used in the control of ectoparasites will also effect endoparasites. Adhering to principles of good practice, for example as laid out by SCOPS, will ensure that we work to limit the generation of resistance to key therapeutic agents so we can continue to effectively treat our farm patients.

KEY POINTS

- Apply a logical approach to a case, considering the importance of herd/flock and individual animal history in such cases.

- Ensure you have kit to collect skin scrapes, as ectoparasites are such a common differential in farm species, and are confident with this diagnostic technique.

- Application of appropriate diagnostic techniques will allow prompt and effective treatment.

- Advise clients on responsible approaches to treatment use to ensure products are effective now and in the long term.