The most common cause of abortion in submissions to Animal and Plant Health Agency (APHA) laboratories is Neospora caninum, according to the Veterinary Investigation Diagnosis Report (APHA, 2021). Identification of an aborting cow and loss of a fetus is the most obvious sign, with the impact of the loss to the herd evident. If this is part of an outbreak or ‘abortion storm’ then the production losses will be even more significant, but this only makes up a proportion of the impact of N. caninum. Not all N. caninum infections will lead to an abortion; cows can exist as carriers of this protozoan parasite with no outward signs, which makes monitoring and surveillance even more important to identify the impact of this disease.

Pathogenesis

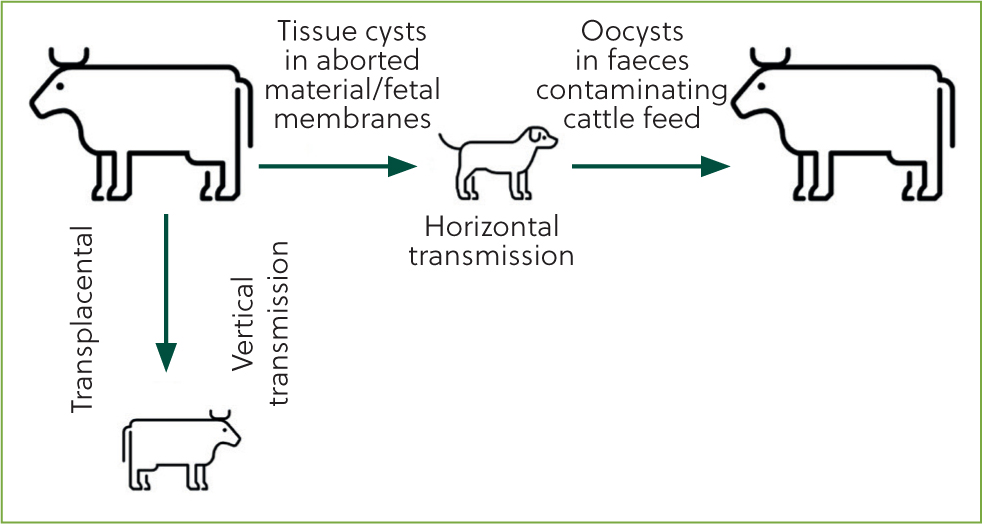

Neospora infection in cattle can occur through vertical transmission (cow to calf) or horizontal transmission (Figure 1). Spread from cow to cow is not possible and this protozoan parasite requires a definitive host to complete the lifecycle. Dogs are a known definitive host. The protozoa has been detected in other wild carnivores, but there is no evidence that they shed oocysts and are unlikely to be the source of on-farm spread in the same way that dogs can be (Stuart et al, 2013). Oocysts have been found present in other mammalian species but there is no known zoonotic risk.

The parasite is shed by infected cows via the placenta, uterine discharge and aborted fetuses. Dogs ingest the parasite and oocysts develop within the gastrointestinal tract. They are shed 5 days or more after ingestion, and shedding occurs from one to several days; reports in the literature show variable periods have been recorded (Dubey et al, 2007). Young dogs are an increased risk for disease transmission as they may shed higher levels of pathogen than older dogs (Dubey et al, 2007).

Once shed in faeces, oocysts can remain viable in the environment for many months. Defecation onto cattle feed stuffs; for example in the feed passage or onto silage, are the main routes for subsequent infection of cattle. However, because of the long viability of oocysts in the environment, infection in grazing animals is also possible. Once infected the consumed oocysts can form cysts within tissue and become latent, evading the immune system and also being undetectable by antibody testing. Further, no clinical signs are evident in newly infected cattle (Dubey and Schares, 2006).

Pregnancy may cause reactivation of the parasite. Little is known about the mechanism of this reactivation but there is speculation that this is related to pregnancy-induced immunosuppression or hormonal imbalances (Lindsay and Dubey, 2020). The outcome of reactivation of the sporulated oocysts is that damage to the placenta and invasion of the fetus by tachyzoites may cause abortion, particularly in the early stages of development of the fetus. Therefore, abortion is seen from 3 months to full term, although most N. caninum-induced abortion occurs between 5 and 6 months of gestation (Lindsay and Dubey, 2020).

Not all pregnancies of infected cattle will lead to abortion; the risk of abortion is three to seven times greater than for seronegative cattle (Davison, 1999; Dubey and Schares, 2006). In the latter stages of gestation, the most common outcome of infection is vertical transmission of the parasite and a congenitally affected calf that is outwardly healthy, and unlikely to be of any significance clinically if it is a male or an animal destined for beef finishing. Now the dam is a carrier of N. caninum and at risk of the effects of reactivation of the parasite during pregnancy, and at subsequent risk of abortion. It is by this mechanism of vertical transmission within clinically healthy animals without abortion that the prevalence in a herd can increase unless monitoring and surveillance are in place.

Diagnosis

Bulk tank milk sampling for N. caninum using antibody ELISA testing has been shown to be effective for identifying endemically infected herds with high seroprevalence (Chanlun et al, 2002). However, in order to identify individual carrier animals and embark on management and control strategies, individual antibody ELISA sampling can be performed through blood or milk testing. Cattle infected with N. caninum frequently show latent infection, so carrier animals can be difficult to identify in a whole-herd screen. Despite an antibody ELISA with high sensitivity (95–100%) and specificity (95–96%) (Bjorkman et al, 1997; Frossling et al, 2003) for detecting exposure to the pathogen around the time of abortion, testing of cattle not showing signs of abortion can give frequent false negatives resulting from low antibody levels (Conrad et al, 1993). Antibody levels in cattle infected but without signs of abortion have been found to be highest 4–10 weeks pre-calving. In order to test all breeding females in the herd reliably, cattle should be sampled during this stage of gestation, with maiden heifers tested for the first time before their first calving.

Accreditation schemes exist with the aim of demonstrating that a herd is free of neosporosis. They can offer cost-effective testing at a herd level, and are based on samples for serological testing across two successive gestations for every breeding female in a herd.

In the UK, all abortions require statutory notification to the APHA in order for Brucella surveillance to take place. Submitting aborted material to veterinary investigation centres allows any causal organisms to be identified through examination of the fetal brain, heart, liver, fetal fluids and placenta. Diagnostic rates arehigher when multiple tissues are examined (Dubey and Schares, 2006). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) on samples of fetal tissue or histopathological examination can definitively diagnose N. caninum as the cause of abortion. It is worth remembering that, in a herd with known endemic infection, abortion in a carrier female might be caused by another pathogen. Serological investigation of aborted materials is valuable, even if a dam is known to be a Neospora carrier.

Management and control

Herd surveillance and analysis of which animals are carriers, including dams of infected individuals, can shed light on the main transmission routes within a herd. For example, it may be that infections can be traced back up family trees to a small number of individuals who have heifers and their offspring in the herd. In this case, control of breeding from these individuals can have a significant impact on further spread within the herd. If these animals are bred to beef no further vertical transmission into breeding stock will occur, as long as horizontal transmission routes are prevented. Because of this, neosporosis can be a satisfying disease to control within a herd once the status of individuals is known.

In the long-term, removal of carrier cows is indicated, but culling of all cattle testing positive is unlikely to be economically justified, especially if the herd prevalence is high and animals are otherwise healthy and have not aborted. Additionally, herds should ensure that bought-in animals are of a known negative status from a herd certified free of N. caninum, because pre-purchase testing may miss latent carriers depending on stage of gestation at the time of purchase. For cattle of high genetic merit, embryo transfer (transplantation of embryos from a known Neospora-positive cow into known negative recipients) is a feasible measure to maintain family lines.

Preventing horizontal spread via the definitive host centres around biosecurity measures: management of calving cows, and associated fetal membranes, as well as handling of aborted material. Immediately securely disposing of afterbirths and aborted material, and preventing dogs from accessing the environment where cows are calving are essential. Furthermore, dogs should be kept away from cattle feeds and feed areas with housed cows in calving boxes (Figure 2), including grazing where forage may be produced. This will be relatively easy in herds with cows housed in calving boxes and without free-roaming dogs present on the farm. In extensive grazing herds it may be much more difficult to control contact with such material, but protecting feedstuffs from dogs present on the farm is worth highlighting as a key element of controlling this disease.

There is no known treatment for N. caninum in cattle. No vaccine is currently available. A vaccine has been developed but has since been withdrawn from the market because of a lack of convincing data on its efficiency (Lindsay and Dubey, 2020).

Footpaths as a risk factor

One aspect that can be outside of the control of farmers managing their grazing is the presence of footpaths crossing pasture. Dogs being walked on footpaths have been implicated in outbreaks and as the cause of endemic issues. It is true that dogs are an essential part of the pathogenesis of this parasite but, for cattle to be infected, the aborted material must be ingested and then defecated onto feedstuffs several days later. Based on this, it seems unlikely that passing dogs could have a significant impact on a herd. Steps can be taken to minimise the impact of footpaths, such as adding signage to make dog owners aware of the risk that dog faeces poses to cattle. It is much more likely that dogs present on the farm are the source of infection, particularly young dogs joining a holding. These dogs are naturally inquisitive in scavenging and are more likely to ingest infected materials and shed oocysts in higher numbers if tissue cysts are ingested. However, aged dogs who may have been historically affected are unlikely to continue to shed oocysts, so removal of existing farm dogs to aid control of neosporosis is unlikely to be of benefit within control strategies.

Herd-level impact

Studies evaluating the effect of N. caninum seropositivity on milk yield are conflicting, but reviews of these studies agree that there is likely minimal impact (Chi et al, 2002; Dubey et al, 2007). The direct costs of neosporosis include abortion, loss of replacement stock, rebreeding costs and an increased risk of culling, incurring additional costs of replacement. Indirect costs include the professional time of a veterinarian involved in abortion outbreaks and the costs associated with diagnosis. In a stochastic model the costs of endemic neosporosis in a 50-cow dairy herd were CAD$2305 per annum (Chi et al, 2002) (equivalent to £1480, at the time of writing). With these costs in mind, there is a justifiable case for ongoing screening and control measures in dairy and beef herds.

Case study

An extensively grazed 30-cow suckler herd was investigated for poor breeding performance. Less than 75% of the breeding females had calved within the breeding season. Investigation of the herd included general assessment of health and condition of the breeding females, including trace mineral investigation. The bull underwent a breeding soundness examination and no issues were identified. Screening for bovine diarrhoea virus and infectious bovine rhinotracheitis, other common causes of poor reproductive performance, found no evidence of these pathogens. Abortion had not been identified as an issue within this herd. However, the cattle were grazed extensively and the herd owner acknowledged that aborted material could be easily missed, so could not be ruled out.

The herd was of unknown Neospora status: having not had any abortions evident in recent years, no diagnostic investigations on such material had occurred. Herd monitoring for other endemic diseases was occurring and it was discussed that Neospora should be considered within this. The multiparous breeding females were sampled. This was carried out at the same time as a tuberculosis test so animals would have been at a variety of stages of gestation. Tail vein blood samples were submitted for serological testing using a commercially available antibody ELISA. At the same time, nine of ten animals tested were found to be in calf; at odds with previous calving performance where a low proportion of the herd had calved. However, given the ongoing presence of the bull and time since the previous calving for the cattle tested (some having not calved in the previous season) it was surprising that many were reasonably early in gestation. It was hypothesised that loss and subsequent pregnancies were occurring without being detected by the herd owner.

The results of serology carried out at this time indicated that six of seven animals tested were found to be positive for N. caninum. These results were surprising to the owner. A risk assessment of the herd was then carried out, including detailed discussion with the herd owner to identify factors that may have contributed to the prevalence and to draw up an action plan for control. Two farm dogs were present (1 and 3 years of age). The dogs were not free-roaming on the holding, but were reported to ‘follow their noses’ at times.

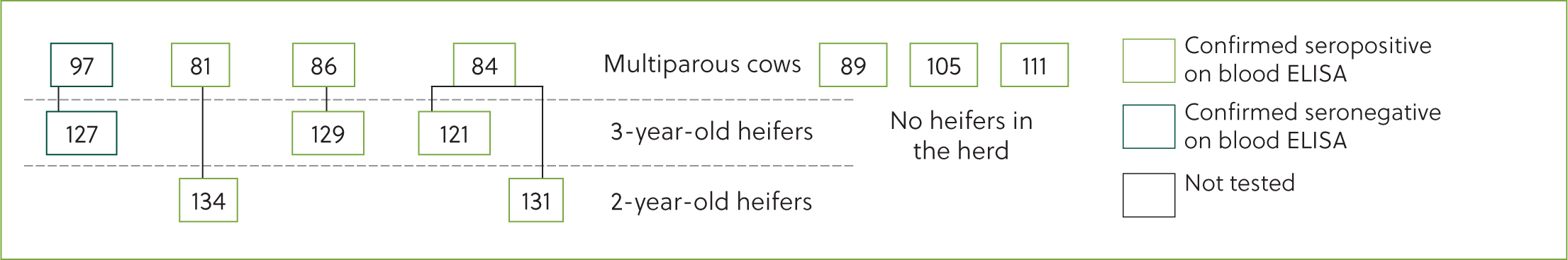

The herd was extensively grazed, with some forage made away from site and fed over winter, and the majority of calving occurred outside. The farmer reported that the dogs were regularly wormed, but this is unlikely to have had any impact on transmission of this protozoa. Additional sampling of maiden heifers (2 and 3 years of age) indicated that the mostly likely explanation was that infection of several dams occurred 3 years previously, in line with when the first dog was introduced. Vertical transmission had subsequently likely occurred and a large proportion of the herd, including maiden heifers identified as herd replacements, were affected (Figure 3). The point source origin in this closed herd was unknown although it is possible that the herd had had Neospora present for much longer at a lower prevalence of negligible impact on fertility and production.

The high prevalence within this herd meant that culling as a method of control was not appropriate. Maiden heifers from known positive dams were identified as not to be kept for breeding, and the potential for buying in replacements in the short term was considered. A focus on breeding replacements from known negatives was advised, together with improved biosecurity around contact between the farm dogs and the herd. Additionally, routine serology for N. caninum was to be included in annual disease screening.

Conclusions

Surveillance data indicates that N. caninum is a common cause of abortion in cattle and routine monitoring for disease presence is likely indicated in dairy and suckler herds alike. Infected cattle do not necessarily abort. Thus, early detection of carrier animals and subsequent control of horizontal transmission (via dogs as a definitive host) and vertical transmission of the pathogen can enable control of reproductive performance before economic impacts are seen.

KEY POINTS

- Infection with Neospora caninum can cause clinical disease through damage to the placenta or latent infection, with reactivation leading to abortion in future pregnancies.

- Transmission of the pathogen can occur horizontally, via the dog as a definitive host. It is suspected that other wild canids cannot shed oocysts and are a less significant risk in the spread of neosporosis.

- Dogs are infected via materials excreted from cows at calving or abortion and shed infective oocysts a few days later. Young dogs shed oocysts in higher numbers, and represent a higher risk for disease transmission.

- Individual milk or blood sampling for antibody testing is required to support decision making on disease control in the herd and management of vertical transmission.