Morbidity attributed to bovine respiratory disease (BRD) has not significantly dropped over the past 45 years (Smith et al, 2020). This is despite a significant body of research and clear advances in treatments, detection technologies and preventatives. So how do we address this? Because BRD is characterised by a complex interaction of many different factors, no single practice for reducing the effect of this disease exists and in fact addressing one factor on its own will often lead to poor results and frustration. For example, simply introducing a vaccination programme for a group of animals kept in sheds that are poorly ventilated and unfit for purpose is unlikely to resolve a BRD issue and will bring about increased frustration and reduced confidence in the veterinary advice and in the vaccines. It is therefore important that when addressing BRD issues on farm veterinary surgeons work with their clients to come up with holistic solutions that address all the risk factors but also take into account the constraints of an individual production system. In addition, and probably most importantly, veterinary surgeons must take into account the needs and perceptions of their clients and work with them to understand their motivation and view of the problem, as only by gaining their ‘buy-in’ can they hope to bring about long-term improvements in the management of this economically damaging disease.

Detection

Accurate and early diagnosis of BRD is a critical facet of any management programme. All too frequently there are delays in identifying animals requiring treatment or an acceptance of a low level of chronic disease within a group. Traditional acceptance of lowlevel chronic disease within a group can be challenged by using scoring systems and benchmarking performance objective parameters such as the number of cases, treatment rates, mortality, and growth rates with other producers. Accurate and early detection can be a harder issue to address. Multiple abattoir studies have highlighted the potential number of cases of BRD that go untreated (Wittum et al, 1996; Williams et al, 2016), and it is important that veterinary surgeons engage with their clients on the importance of accurate and early diagnosis, and provide training where required to ensure that all members of the farm team involved with the livestock are aware of the symptoms to look out for.

The desire for more accurate and rapid detection has driven a large amount of technology development in this area and it is likely that this will continue in the future. Currently commercially available systems focus on the use of thermography and accelerometers (Potter, 2020) and these are being used as a means of identifying animals with disease. With the focus on the responsible use of antimicrobials in agriculture worldwide it seems logical to expect that the veterinary profession will be increasingly looking to technology and rapid diagnostics not only to identify disease, but also to provide a robust definition of whether antimicrobial treatment is required. Some preliminary work by Mahendran et al (2017) demonstrated some potential for the use of technology to enable non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to be used alone in early cases of BRD, but we are still a way off from the aspiration of having a rapid and accurate means of indicating which cases of BRD do not require an antimicrobial.

Looking across the farming sector there is increasing interest in ‘precision agriculture’. A term most often applied to crop production, it refers to the practice of collecting data with a high degree of spatial or temporal resolution, then using the information to precisely target treatments or manipulations to areas most likely to benefit. Although the livestock sector has lagged behind plant production in the adoption of precision agriculture, some advancements are now being seen in this area, and in the future BRD control could be substantially improved by precision agriculture practices. Potential advancements include methods to remotely detect sick cattle, to accurately and rapidly identify respiratory inflammation or infection, and to identify cattle likely to become sick, or stay healthy, based on their genetics, gene expression, normal flora, or metabolism.

Treatment

Effective treatment must begin with a commitment to early identification and treatment of animals with BRD and the role of the veterinary surgeon and the potential role of technology have already been considered. A review of the NOAH compendium will identify over 50 antimicrobial products licensed for the treatment of BRD in the UK. While each of these products will have different pharmacokinetic properties (T-max, C-max etc), clinically the rate-determining steps in achieving effective concentrations at the site of infection are most likely going to be how rapidly the diseased animal is identified and how quickly steps are taken to administer treatment. The speed of treatment is not primarily a function of the onset of therapeutic activity of a particular antimicrobial, but the ability of the farmer to consistently recognise sick calves early in the course of disease and administer a proven antimicrobial.

A common discussion on farm with respect to BRD are the ‘treatment failures’, those frustrating cases where despite perceived rapid and accurate detection and management the farmer is still left with an animal with chronic lung damage. In the same way that BRD is driven by complex interaction between host, pathogen and the environment, many BRD treatment failures are found to result from interactions between the host, pathogen, environment, treatment, and treatment administrator (Booker, 2020). There is a tendency for treatment failures to be immediately blamed on antimicrobial resistance, and while there is evidence of antimicrobial resistance among the common BRD pathogens (Veterinary Medicines Directorate, 2020), often treatment failures can be traced back to errors or delays in disease detection, errors in medicine handling and administration or poor host immunity resulting from management factors such as failure of passive transfer or a poor environment Booker, 2020). It is important, therefore, that rather than glossing over the treatment failures and chronic cases during farm reviews, veterinary surgeons use them as discussion point for the management of BRD and look at ways of preventing them in the future.

Use of vaccination

As veterinary surgeons strive to further reduce the use of antimicrobials on farm the use of vaccination in the management of BRD is an area of particular focus with widespread initiatives aiming at increasing vaccine uptake within the industry. Veterinary surgeons are privileged to have several different vaccines available to them, however market penetration is not as high as it could be. With numerous different licensed vaccines available and different programmes, it is difficult to put exact figures on current BRD vaccination within the UK. Figures from the AHDB (2022), which are based around the assumption that all respiratory vaccines are used in animals that are under 1 year of age and that all sales are to provide a primary dose, have shown a steady increase in the uptake of vaccines for pneumonia, from 29% of all cattle under 1 year of age in 2011 to 44% in 2021 — an increase of 51%. The recent RUMA target task force report (RUMA 2020) highlights respiratory disease as a key area of antimicrobial use and will be looking for a further rise in vaccine uptake (alongside reduction in lung lesions at slaughter) as a success measure for its aim to achieve a reduction in risk of conditions by 2024.

When considering vaccination programmes, it is important to look at the specific set of disease challenges and risk factors present on each farm; there is not a ‘one size fits all’ programme for BRD. Vaccines must be used as an intervention at the critical control point in BRD pathogenesis rather than being administered to high risk, stressed calves under high infection pressure. Joint decision making with the farmer is important when deciding on a vaccination strategy on-farm (Kristensen and Jakobsen, 2011). The implementation of vaccination programmes can either be reactive (i.e. in response to a disease outbreak with farmers motivated to vaccinate because they can see the disease firsthand) or proactive (i.e. in response to a perceived risk). The reactive discussion is often easier because the evidence of the problem is right in front of the client and they are looking for solutions, while the proactive discussion is based more around risk and potential problems and therefore requires a slightly different approach. When discussing vaccination programmes, it is important to address the key barriers to adoption such as cost-benefit and previous problems with vaccines, and provide evidence to clients of why vaccination is justified (Elbers et al, 2010). Table 1 summarises reasons farmers have stopped or never implemented BRD vaccination ranked based on feedback from a recent survey (calfmatters 2020) and highlights several potential areas that need to be addressed in conversations with clients.

Table 1. Reasons why farmers stopped vaccinating in 2020 (Calfmatters, 2020)

| Rank | Reason for stopping or not implementing bovine respiratory disease vaccination |

|---|---|

| 1 | No incidence of calf pneumonia |

| 2 | Reduced incidence of disease due to other changes |

| 3 | Treating individual cases is cheaper |

| 4 | Upfront cost of vaccination |

| 5 | Veterinary surgeon has not suggested vaccinating |

| 6 | Unsure of the benefits of vaccinating |

| 7 | Lack of time/staff to vaccinate |

| 8 | Previously vaccinated, but saw no health improvement |

| 9 | Too difficult to vaccinate |

| 10 | Previously vaccinated, but saw no production gain |

| 11 | Veterinary surgeon has advised against vaccinating |

Once vaccination programmes are in place it is important that they are regularly reviewed and audited. Concerns over compliance with vaccination programmes are widely acknowledged (Cresswell, 2013), but simple steps such as reviewing medicines records to discuss timings, checking how vaccines are stored on farm (Williams, 2018) and reviewing practice sales records to ensure timely reminders of boosters etc. can all bring about changes on farm which can help ensure vaccine efficacy.

Implementing change

Having identified a problem with BRD on farm how can veterinary surgeons go about working with their clients to bring about long-lasting change on farm? The importance of innovation and change within organisations has been repeatedly highlighted and has the been the topic of significant research. From this many theories have emerged often with the common theme, that change is composed of a number of stages (events, decisions and actions) connected in some form of sequence. If change is considered as a process of a series of stages, veterinary surgeons can potentially use those stages as a route map to guide them (and their clients) through the change.

The three-stage model of planned change originally proposed by Lewin (1947, 1951) suggested that for successful change to occur there were three stages: unfreezing, shaping and refreezing. The first stage, unfreezing, considers the individuals' and organisations' motivation for change and how they identify the need for and become comfortable with the change. During the shaping or moving stage, plans are made for implementation of the change. Finally, the refreezing stage sees the change becoming permanent.

Taking this concept onto farm it is important that veterinary surgeons work with their clients to engage them with the need for change. Motivations will vary depending on the client's perspective. Some will want to take steps towards disease prevention and the avoidance of future BRD outbreaks, while others may be more performance driven and be motivated by a desire to reduce losses and improve growth rates. Other clients will be driven by the requirement to reduce antimicrobial usage or the need to adhere to specific producer contracts. Only by truly engaging with farmers on the need to change and address the issue of BRD will veterinary surgeons be able to drive management changes on farm. Table 2 shows some of the potential impacts BRD has on farm businesses ranked in order of perceived importance in a recent survey of UK farmers (Calfmatters, 2020). Looking through the list it is possible to gather data from farm and practice records to start putting actual figures to the costs for many of the potential impacts. By using a client's actual farm data it is possible to provide a much better evidenced argument for the need to change rather than relying on the published costs of a case of pneumonia which clients sometimes struggle to relate to.

Table 2. Potential impact of BRD on farm businesses ranked based on responses to the Calfmatters survey 2020

| Rank | Potential impact on farm business |

|---|---|

| 1 | Increased vet and medicine cost |

| 2 | Loss of income from less productive calves |

| 3 | Loss of income from dead/culled calves |

| 4 | Personal/staff stress from additional management |

| 5 | Increased time to finishing/bulling weight |

| 6 | Increased staff time and costs |

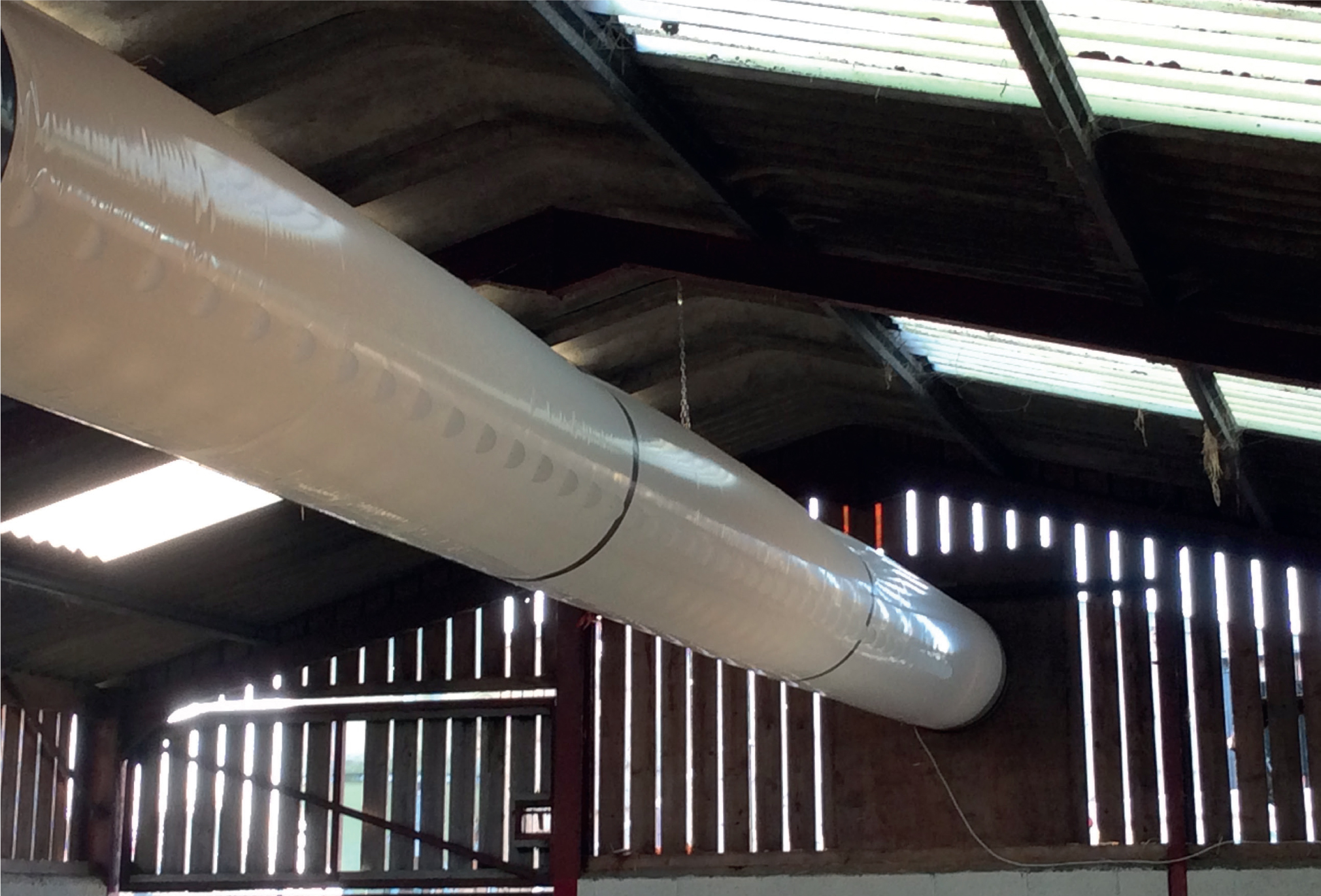

Having established the need for change it is possible to move onto the shaping stage where there is a need to develop a holistic plan to address the disease and come up with a farm specific plan. During this phase it is essential that the plan addresses the perceived issues around the disease but also comes up with effective and achievable solutions. If the environment is an issue, simply telling the client they need a new shed achieves very little, while working through simpler and more cost-effective ways of modifying existing infrastructure can bring about significant improvements. For example, positive pressure tube systems can be retrofitted to most buildings and can bring about a dramatic change in how a building ventilates for relatively little investment (Figure 1). If the plan to manage/reduce disease includes a vaccination programme it is important to acknowledge the time and effort it takes to do this and work with clients to design something that provides the protection they require while fitting into their system.

Once a change has been made it is important to monitor the effect and understand from the farm team what is working, and where the ongoing issues lie. Performance data (medicine spend, growth rates disease incidence etc.) from before and after the change can be used to demonstrate effect and return on investment, and discussions with the farm team can help identify any ongoing issues that need to be addressed. This discussion and follow up is an essential part of the process and should form part of the dynamic health planning process.

Conclusions

BRD remains a significant challenge for the cattle industry. If veterinary surgeons are going to make significant advances in reducing its impact it is essential for them to work closely with their clients to develop practical disease control programmes that address the farm specific risk factors in a holistic manner.

KEY POINTS

- Bovine respiratory disease (BRD) remains a significant economic and welfare issue to the cattle industry worldwide.

- Accurate and early diagnosis of BRD is a critical facet of any management programme and this is increasingly being facilitated by new technology.

- Although vaccines offer a good way of reducing the risk of BRD on farm their market penetration remains low.

- There are a multiple perceived barriers to the use of vaccines on farm and it is essential that veterinary surgeons work with their clients to understand these and work to overcome them.

- When working to bring about change on farm, veterinary surgeons must understand their clients' motivations and work with them to implement the appropriate disease control strategies.