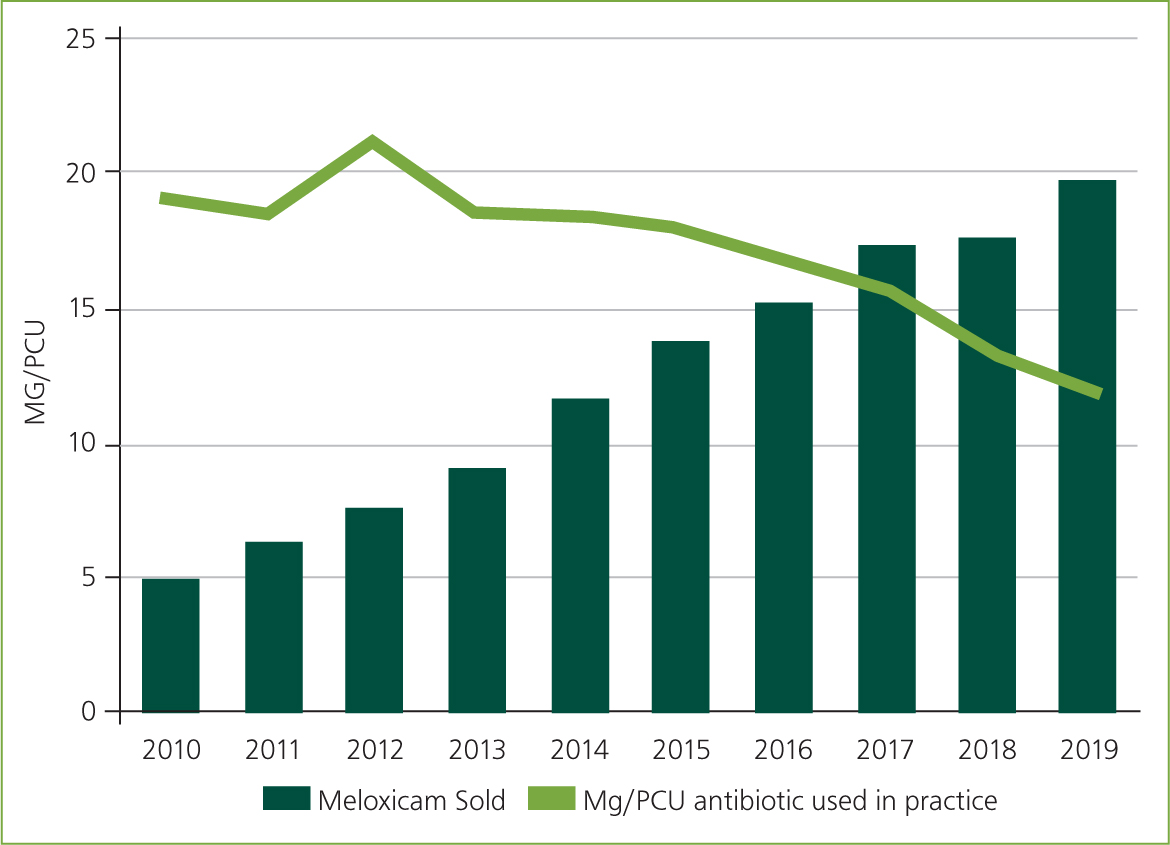

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have long been used in the farm veterinary world, with licensed oral and injectable suspensions readily available on the market. However, one of the authors remembers NSAIDs being only used for ‘special cases’ where the farmer had a highly valued animal! They are now considered a staple in any veterinary surgeon's car and used commonly in conjunction with other medicines or alone, to treat a range of diseases. More NSAIDs are being used than ever before (see Figure 1).

There is now unequivocal evidence demonstrating the benefits of NSAIDs in the management of bovine disease. This includes mastitis (Fitzpatrick et al, 2013,) respiratory disease (Selman et al, 1986) and more recently lameness (Thomas et al, 2015). However there is also good evidence that the use of these NSAIDs has a benefit in routine procedures such as disbudding and castration (Hudson and Reader, 2014).

Mode of action

NSAIDs work by targeting the pro-inflammatory pathway and preventing synthesis of proinflammatory substances. They prevent the conversion of arachidonic acid into prostaglandins and thromboxane, by inhibiting the actions of the cyclo-oxygenase (COX) enzymes. The COX enzymes are easily targeted and can mainly be divided into COX-1 or COX-2 (Abramson et al, 1989)

COX-1 is found in almost every cell and considered to be beneficial to the body. Its products primarily act to protect against unwanted blood clotting in the vasculature and prevent mucosal ulceration within the gastrointestinal tract. The same cannot be said for the products made by the COX-2, which act mainly to increase local pain and inflammation, and induce a systemic fever.

NSAIDs target these pathways to reduce inflammation, pyrexia and platelet aggregation, as well as provide analgesia. These are four of the five main properties of NSAIDs, the other being an anti-endotoxin effect. The first NSAIDs commercially available were non-specific and targeted both the COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes. However, newer formulations have been created that are selective to COX-2 only. Favoring COX-2 inhibition theoretically decreases the amount of unwanted side effects of NSAID use, as the beneficial products of COX-1 are still produced (Stock et al, 2015).

Many NSAIDs are licensed for use in cattle, with active ingredients such as ketoprofen, flunixin and meloxicam being those predominantly used (Table 1). Ketoprofen is a non-selective COX inhibiter, while meloxicam has demonstrated COX-2 selectivity in horses, rats, cats and dogs (Newby et al, 2014).

Table 1. A summary of some of the most commonly available NSAIDs licensed in farm animals in the UK

| Active ingredient | Example product name | Product licences include | Route of administration | Half life | Dose rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meloxicam | Metacam (Boehringer Ingelheim)Recocam (Bimeda)Rheumocam (Chanelle Pharma)Inflacam (Virbac)Loxicom (Norbrook)Meloxidyl (Ceva) | Treatment of acute respiratory infection with antibiotic therapyCalves with diarrhoea over 1 week of age with rehydration therapyTreatment of acute mastitisPostoperative pain relief following dehorning in calves | SubcutaneousIntravenous | Approximately 26 hours in young cattle, 17 hours in adult cattle following subcutaneous administration | Single dose at 0.5 mg meloxicam/kg bodyweight |

| Ketoprofen | Ketofen (Ceva)Dinalgen (Bayer)Rifen (Chanelle Pharma)Nefotek (Bimeda)Ketodolor (Virbac)Kelaprofen (Kela) | Reducing pain from lamenessReducing post-partum udder oedemaImproving recovery rate from acute mastitisReducing pyrexia and distress associated with bacterial respiratory diseaseSupportive treatment of parturient paresis | Deep intramuscular (IM) injectionIntravenous | Approximately 2 hours following IM injection | 3 mg ketoprofen/kg bodyweight once daily for up to 3 days |

| Flunixin meglumine | Finadyne (MSD)Allevinix (Ceva)Flunixin (Norbrook)Dugnixon (Global Vet Health) | Control of acute inflammation in respiratory diseaseAdjunctive therapy in acute clinical mastitis | Intravenous | Approximately 4 hours | 2.2 mg flunixin meglumine/kg bodyweight at 24-hour intervals for up to 5 days |

| Flunixin transdermal | Finadyne Transdermal (MSD) | Reduction of pyrexia with acute respiratory disease and acute mastitisReduction of pain and lameness associated with interdigital phlegmon, interdigital dermatitis and digital dermatitis | Pour-on | Approximately 8 hours | Single application at 3.33 mg flunixin/kg bodyweight |

These products are not exclusive to these active ingredients. Information correct at time of printing — authors accept no responsibility to information regarding use of these products. Please refer to specific data sheets.

In previous studies, farmers have proved to be reluctant to use NSAIDs following concerns regarding their cost (Huxley and Whay, 2006). However, this attitude is gradually changing in a positive way, as availability of NSAIDs increases and the costs of buying them decreases (Remnant et al, 2017). Licensing for specific diseases, duration of action, familiarity and milk withdraw times commonly influence a farmer's decision on which one to use. Following the cascade, they are also commonly used in sheep, goats and alpacas, but UK licensing has not yet been acquired in these species, so standard milk/meat withdraw times must be adhered to.

Veterinary use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs on farm

The use of NSAIDs among veterinary surgeons in individual cases of illness/pyrexia as well as routine husbandry procedures (such as disbudding and castration) has increased somewhat in the last decade. However, further uptake is required to safeguard animal welfare (Remnant et al, 2017) at a time that the industry comes under increasing scrutiny.

Major veterinary surgery is one area where NSAIDs are frequently used, but timing and route of administration may vary depending on the clinician. It has been shown that the duration of analgesic effects is greatly increased when given before the onset of noxious stimuli (Alexander, 2013), therefore animals undergoing surgical procedures such as Caesarean section or correction of a displaced abomasum should receive non-steroidal analgesia prior to surgery. Route of administration is also an important factor and, where possible, the intravenous route is preferable for these procedures because of a more rapid speed of onset; although, if intravenous access is not possible because of safety concerns, pre-operative administration via subcutaneous or intramuscular route is required and preferential to no administration. The use of NSAIDs is part of a multi-modal approach to anaesthesia and pain relief for any planned surgical procedure.

Disbudding and castration

In recent years, NSAID use has expanded to more routine procedures such as castrations and disbudding (Figure 2). Research has demonstrated that calves continue to display signs of pain when the local anaesthetic effect wanes when NSAID is not administered, compared with those where an NSAID was used (Stewart et al, 2009; Webster et al, 2013). Findings such as these are being reflected in farm assurance schemes and milk contracts as discussed below, as well as British Veterinary Association (BVA) policy. However, pain assessment for these procedures, and therefore non-steroidal use, varies somewhat among practitioners (Remnant et al, 2017). To safeguard welfare and avoid contract and policy disputes, practitioners and farmers should use NSAIDs, alongside local anaesthetic, when these procedures are performed.

Disbudding (whether by thermal or chemical cautery) and castration (whether carried out surgically or by ‘bloodless’ methods such as using rubber rings or burdizzo) cause both acute pain at the time of the procedure and chronic pain, as evidenced by behavioural change, for a variable time following the procedure (Robertson et al, 1994; Graf and Senn, 1999). Routinely used local anaesthetic agents have a short duration of action (1–2 hours), and studies have shown an increase in pain response around 1–4 hours after disbudding (Stewart et al, 2009; Stafford and Mellor, 2011). Pain following disbudding with a local anaesthetic may be present for 44 hours after the procedure.

NSAIDs such as meloxicam with a half life of 26 hours have been shown to be effective for up to 3 days, and are able to reduce pain up to 44 hours in the postoperative period (Heinrich et al, 2010). A check in growth rate following these procedures can also be mitigated by NSAID treatment (Coetzee et al, 2012).

Farm assurance schemes and milk contracts

Defra (2003) recommended that following dehorning, all animals should be given appropriate pain relief. Following this latest published research the British Cattle Veterinary Association (BCVA) and BVA have issued a joint statement regarding analgesia in calves (BVA/BCVA, 2017).

In recent years, Red Tractor Assurance schemes have made it a requirement that all health plans are written and updated in conjunction with a veterinary surgeon. When creating these, they must include a policy regarding when administering pain relief is required on the farm, which products to use (almost unanimously NSAIDs), who is responsible for the administration of these and how treatments will be correctly recorded.

In addition to this, many farms must adhere to more specific guidelines, set out by their milk buyers (Table 2). For example, many contracts now require the administration of NSAIDs for routine husbandry procedures, such as calf disbudding, as well as treatment for lame cows and certain grades of mastitis. Many also require farmers to complete medicine education courses (e.g. Milksure), run by their veterinary practice, with the aim of educating them on the properties and appropriate uses of NSAIDs and other medicines.

Table 2. Summary of some of the common retailer/farm assurance requirements

| Assurance Scheme/Body | Castration | Debudding | Mastitis | Lameness | Miscellaneous |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TESCO (TDSG) | Required | Required | Mobility score 3 cows | Any bovine requiring pain relief | |

| Sainsburys | Required | Required | Required if quarter changes | ||

| ARLA 360 | Required | Required | Any ‘udder/foot/reproductive invasive procedure’ | ||

| RSPCA | Required | Required | Refer to vet HHP | Any procedures that are painful or may induce pain, e.g. therapeutic foot trimming | Removal of supernumerary teats |

| BVA/BCVA | Recommended | Recommended | |||

| Red Tractor | Written policy included in HHP |

NSAID use is indicated on farm in many other areas for safe-guarding welfare and improving productivity. The following sections discuss the use of NSAIDs in these areas, where use can be expanded and in appropriate circumstances, can assist in reducing antimicrobial usage on farm.

Mastitis

As well as being a significant economic and welfare issue on dairy farms, mastitis is also an area of considerable antimicrobial use (Hyde et al, 2019). In recent years this has been improving, particularly with the use of selective dry cow therapy, but with new technology alongside non-steroidal use, a further reduction could be achieved.

For welfare reasons, the analgesic effect of NSAIDs makes them important components of treating mastitic cows, even in mild cases (Kemp, 2008). Recent research shows the addition of NSAIDs to mastitis therapy also has significant benefits in increasing conception rate for cows with clinical mastitis during the first 120 days in milk. This improved conception rate resulted in fewer inseminations, reduced feeding costs and a decreased culling rate, making it a cost-effective intervention for the farmer (van Soest et al, 2018). In toxic mastitis cases, the anti-inflammatory, anti-pyretic, anal-gesic and specifically anti-endotoxic properties of NSAIDs make them a vital component of treatment alongside fluid therapy and antimicrobials where appropriate. However, by the time a cow is showing toxic signs, the use of antimicrobials is controversial, and this article will not discuss this argument further, and will rather emphasise the importance and reasons for using NSAIDs.

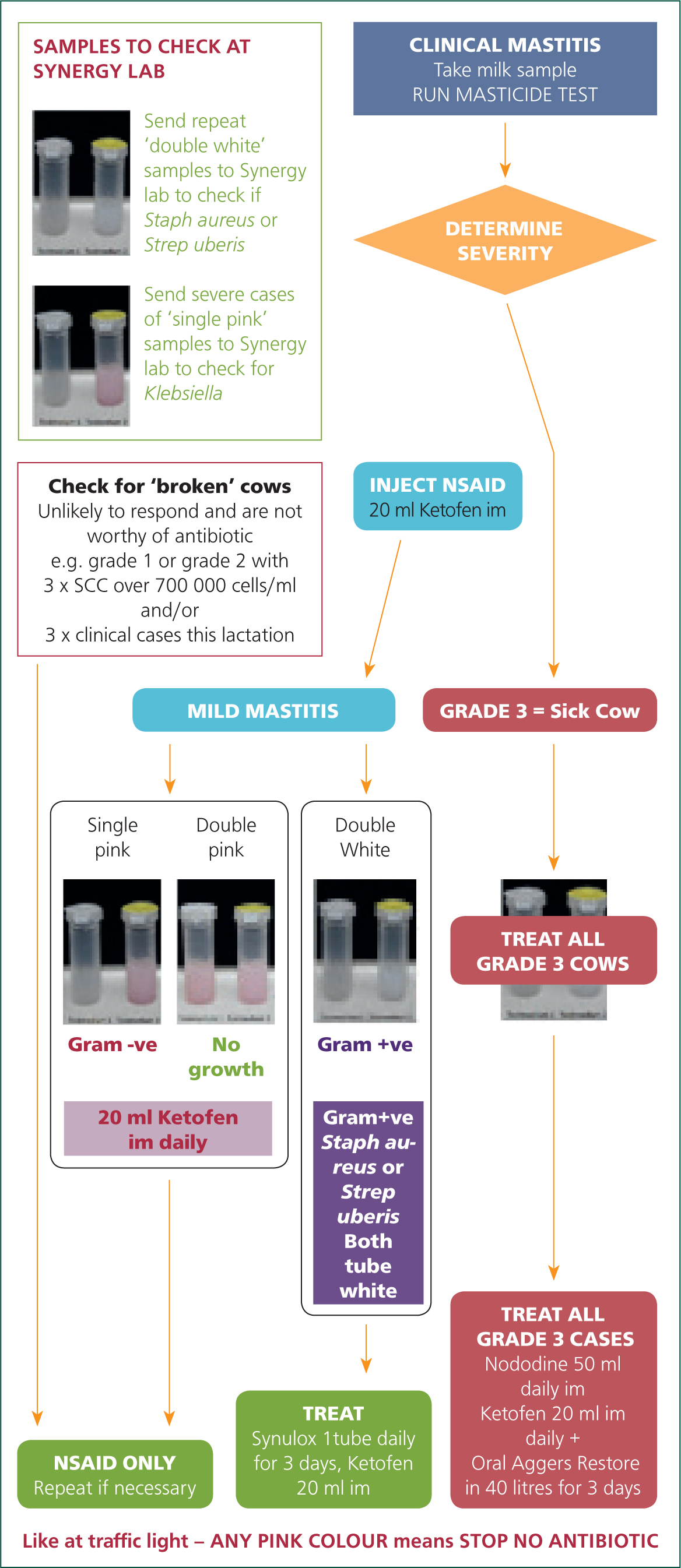

As technologies such as on-farm culture have been developed and become commercially available (Figure 3), this has the potential to further reduce antimicrobial use, with NSAIDs becoming the only treatment for clinical mastitis. In cases of Gram-negative mastitis, antimicrobial therapy is often not indicated and will usually self-cure. Where on-farm culture is in use, once these cases are detected, an NSAID can be administered in the first instance while awaiting results from a milk culture. In appropriate circumstances, this can reduce antimicrobial usage as well as save costs on treatment and milk losses. It should be noted that this may not be a viable option on all farms, and cost effectiveness will depend on the proportion of Gram-positive cases on farm (Down et al, 2017).

Figure 4 shows a flow chart on the use of on-farm culture and how to interpret results to guide treatment options.

In summary, all cases of clinical mastitis should be treated with a NSAID with multiple benefits and to improve cow welfare. There are cases and technology which may allow NSAID therapy to be reached for instead of an antibiotic, but these should be chosen carefully with proper knowledge of the farm and case in question.

Lameness

In recent years, provision of NSAIDs to lame cows has become more common practice, as farmers do consider pain and suffering as one of the most important outcomes of lameness (Leach et al, 2010).

Pain relief in lameness has been a topic of recent research. Thomas et al (2015) demonstrated that the use of a NSAID (ketoprofen for 3 days) in conjunction with a block and a therapeutic trim was the most effective treatment for recently detected claw horn disease. The mechanism of the treatment was, however, unclear, and it was not known whether the NSAID reduced inflammation and further damage to the corium, alleviating pain from the lesion, or if discomfort was prevented by the presence of the block (Figure 5). However, it is important to temper expectations when interpreting this study. The positive effect of this treatment protocol was only seen when cows were treated immediately after detection. When cows had been lame for a longer period of time, there was no significant effect. This is not to dismiss the benefits of pain relief for a claw horn lesion, but more importantly to highlight the need for early effective treatment in a case of lameness.

Our understanding of the effect of the use of NSAIDs in the management of lameness is still unclear. Was the effect of the NSAID in this study due to genuine pain relief or maybe in fact due to the anti-inflammatory effect of the NSAID? Work is on-going in relation to the aetiology of claw horn lesions. Newsome et al (2017) showed how with respect to inflammation, lameness events can lead to bone destruction and new bone growth, and promote further inflammation. In terms of lameness, inflammation stimulating different pro-inflammatory pathways can promote changes in fat pad globules, with the consequent increase in local inflammation, leucocyte activation and cellular damage, therefore compromising the normal characteristics of the fat tissue (Osorio et al, 2012).

It is also important to remember that often the physical action of treating an animal can lead to pain. Janßen et al (2016) demonstrated that treatments of claw horn lesions caused a significant stress and pain reaction in acutely lame cows, demonstrating the necessity of adequate pain management protocols for such interventions.

Farmers often do not refer to mild cases of lameness as ‘lame’, and there is often a delay in farmers spotting lameness (Leach et al, 2010). With more chronic cases, it has been shown that NSAID administration and trimming has little effect on rate of recovery, and that in fact, early identification and treatment are the most important factors in achieving soundness (Thomas et al, 2016). While it may not influence locomotion scores in chronic cases, some NSAIDs (in this case, ketoprofen) have been shown to decrease the hyperalgesia associated with many chronic lesions (Whay, 2005).

Youngstock health

This section discusses the current use of NSAIDs when treating sick youngstock, more specifically those suffering from bovine respiratory disease (BRD) and scour. It also looks into possible future uses of non-steroidals and their potential to reduce antimicrobial usage in these cases.

Calf diarrhoea

Meloxicam is currently licensed for calves with diarrhoea from 7 days of age. The majority of these cases would be expected to have viral or protozoal causes, which would mean in theory antimicrobials are not required. It should be noted that in severe cases antimicrobials are often indicated for secondary infection, although this should be considered on a case by case basis. Often NSAIDs, such as meloxicam, in combination with oral fluid therapy work as an effective first-line symptomatic treatment. The authors would use, or recommend this to farmers, as a routine treatment for scouring calves of this age for welfare reasons, and also to improve future performance with increased milk consumption and daily liveweight gain pre-weaning (Todd et al, 2010). Early detection and treatment of these cases improves prognosis and therefore decreases requirement for antimicrobials. It is worth noting, however, in animals that become acidotic and recumbent as a result of scouring, further veterinary attention is vital.

Calf pneumonia

Another area of calf health where NSAIDs are of great benefit is in cases of BRD. There are multiple preparations available that combine an antibiotic with an NSAID, which are frequently used as first-line treatments in BRD. Early detection and treatment of pneumonia cases are vital to improve response to treatment and future daily liveweight gains, which has been shown to be the greatest cost associated with the disease (Andrews, 2000). With the initial pneumonia pathogens being predominantly viral (with the exception of Mycoplasma bovis), this presents a potential opportunity for the use of NSAIDs alone as a first-line treatment. If a case is diagnosed at the viral stage, e.g. pyrexia and serous nasal discharge, an argument could be made for NSAID only treatment. Evidence on this is currently limited (Mahendran et al, 2017), but it should be considered as a potential practical application and certainly an area for further investigation as the industry becomes under increased pressure to reduce macrolide antibiotic use, which is frequently prescribed for such cases.

In the calf-rearing sector, recent studies have investigated the effect of prophylactic, in feed NSAIDs (sodium salicylate — Solacyl, Dechra). These were given on arrival at the calf rearing units, which led to a reduction in overall antibiotic usage (Atkinson, 2018). Prophylactic NSAID administration is not currently commonplace, but as we continue to strive to reduce antimicrobials wherever possible, this represents an important future consideration in the appropriate settings.

Use of technology, such as fever tags, are other areas that should be also explored to assist in early detection of calf disease as well as increased availability of animal side tests.

Dystocia

The roll of NSAIDs, for both dam and calf, in dystocia has generated much debate and research. Laven et al (2012) reviewed the literature and concluded that there was no benefit to blanket treatment of all calving cows with NSAIDs, but it was of use in certain situations. In recent years, the authors feel that responsible breeding and improved cow management has seen levels of dystocia reduce.

Tissue swelling and bruising are more commonly seen after difficult calvings and may justify NSAID treatment in order to prevent pain and suffering in the dam (Figure 6). Farmers interpret dystocia as one of the most painful conditions in cattle (Kielland et al, 2010), but will use NSAIDs in these situations less commonly when compared with other conditions (Remnant et al, 2017). Huxley and Whay (2006) reported that 66% of veterinary surgeons used NSAIDs after attending a dystocia.

Previous work has been done to study whether administration of NSAIDs around calving can not only manage pain, but also have a positive effect on levels of periparturient and future diseases. It has been shown that administration of meloxicam to dairy cows around calving results in a significant increase in milk yield for the subsequent lactation (Swartz et al, 2018), as well as achieving higher milk protein (Carpenter et al, 2016). Within the same study, there was also a suggestion that NSAID administration after calving could influence longevity in the cow, but more work is needed to confirm this.

Interestingly, administration of flunixin around calving has previously been discouraged, after one study found that cows that had received the NSAID shortly before birth had increased levels of retained fetal membranes (RFMs), metritis and stillbirths, and as a result, decreased milk yields (Newby et al, 2017). This is not the case for all NSAIDs, with meloxicam administration being shown to have no effect on RFM levels (Newby et al, 2014), and ketoprofen may actually decrease the levels of RFM (Richards et al, 2009).

It is known that dystocia can also negatively influence a calf's health, with assisted calvings leading to calves with less vigor (Barrier et al, 2012; Murray et al, 2016). This is exacerbated if these calves do not then receive adequate colostrum. Administration of meloxicam to newborn calves may have a positive effect on suckle reflex and vigor and, as such, may have the potential to positively influence pre-weaning calf health. This is supported by a study demonstrating that giving ketoprofen in newborn calves leads to less calf recumbency and more social activities within the first 48 hours of life (Gladden et al, 2019). This may have a significant welfare benefit to calves, but long term, the benefits have not been evaluated.

Pearson et al (2019a) demonstrated that administration of meloxicam to all beef calves at birth, did not affect the average daily weight gain (ADG) to weaning or transfer of passive immunity. The authors suggested that, instead, the importance lies in correctly identifying higher risk calves, and achieving good colostrum management. These calves are often the calves born following dystocia, and it has been shown that administration of meloxicam to this sub-group may significantly improve their ADG within the first week of life (Pearson et al, 2019b); however, again in this study, the difference in ADG at weaning was insignificant.

Conclusion

The recognised benefits of NSAIDs in cattle practice are widespread, although their prescription and recommended use could still be further increased among veterinary practitioners. As new research and technologies are constantly developing, we are increasingly being presented with further opportunities to improve welfare on UK farms through NSAID usage, as well as the potential to reduce antimicrobial usage. With the ever-increasing scrutiny on these areas of the industry, NSAIDs are becoming more important to both the farm veterinary profession, as well as many farm assurance schemes and contracts.

KEY POINTS

- Increasing evidence to demonstrate the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in the management of bovine disease.

- NSAID use is increasing while antimicrobial use is reducing.

- Farmers' attitudes to NSAIDs are changing in a positive way.

- NSAIDs are recommended to be used for all disbudding and castration.

- There is good evidence to support NSAID use in conjunction with block application for treatment of claw horn lesions.

- NSAIDs are important for mastitis cases when ‘on-farm culture’ is being used.

- Consider NSAIDs for all cases of dystocia.