According to Vandeplassche, diagnosis of Mycoplasma spp. mastitis ‘usually comes too late’ (Vandeplassche, 1985). Once infected, Mycoplasma spp. are not sensitive to licensed treatments and cows can take months to years to self-cure (Ruhnke et al, 1976). During this time infected cows can shed Mycoplasma spp. in high numbers, and pose a contagious risk to other cows during the milking process (Divers and Peek, 2007). The most frequently reported symptom is recurrent mastitis that is non-responsive to treatment, however the other indicators of a Mycoplasma spp. outbreak are listed in Box 1.

Box 1.Criteria of Mycoplasma spp. mastitis outbreaks

- Chronic, recurrent mastitis — non-responsive to broad spectrum treatment

- Mastitis often presents in early lactation (<30 days in milk). 1st lactation cows are at increased risk

- Typically associated with contagious spread:

- High proportion of chronically high cell count cows (>20%)

- Poor dry period cure rates (<60%)

- High bulk somatic cell count

- Often poor biosecurity, e.g. purchasing of lactating cows

- Disease co-morbidity — calf pneumonia, polyarthritis

Most outbreaks are associated with Mycoplasma bovis, however several other species have been isolated from bovine mastitis including Mycoplasma arginini, Mycoplasma bovirhinis, Mycoplasma californicum, Mycoplasma canadense, Mycoplasma dispar (Fox, 2012). Veterinary surgeons should consider this when choosing a diagnostic approach, as tests that are specific for M. bovis will not detect these other species.

Before undertaking a Mycoplasma spp. investigation, veterinary surgeons should also consider other differentials for these symptoms. For example, Box 2 shows some of the pathogens that are more commonly isolated from recurrent cases of clinical mastitis. Whenever testing for Mycoplasma spp., veterinary surgeons should also submit milk samples for routine bacteriological culture, according to standards defined by the National Mastitis Council (Adkins et al, 2017).

Box 2.Pathogens frequently isolated from cases of recurrent mastitis

- Streptococcus uberis

- Staphylococcus aureus

- Streptococcus dysgalactiae

- Klebsiella spp.

- Serratia spp.

- Pseudomonas spp.

This article will discuss approaches to Mycoplasma spp. mastitis investigation including both individual animal and herd level approaches.

Individual animal testing

When investigating Mycoplasma spp. mastitis outbreaks, clinicians are left with three main groups of tests:

- Bacteriological culture (milk) — all Mycoplasma spp.

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR, milk) — M. bovis or multiplex

- Antibody enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (milk or serum) — M. bovis only.

Bacteriological culture

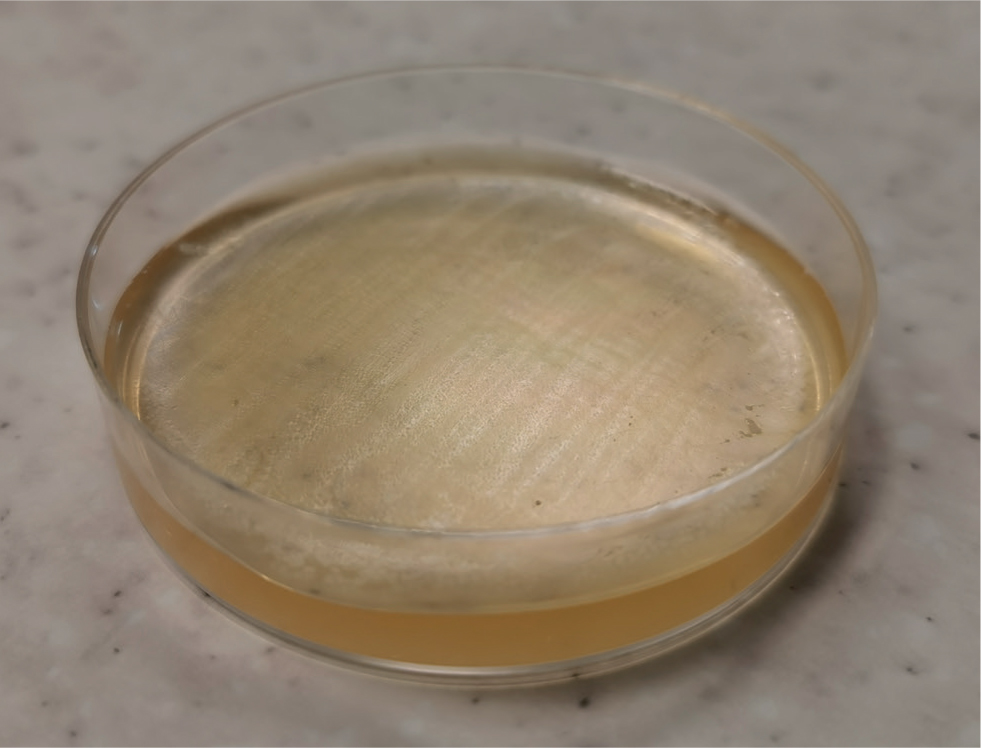

Bacteriological culture is the oldest method of detection, and is often used as the reference standard in published research. For this reason, it is difficult to quantify the sensitivity and specificity. Due to its atypical morphology and intracellular lifecycle, Mycoplasma spp. is a difficult species to culture by conventional bacteriological methods. Mycoplasma spp. should therefore be plated on selective growth media, and incubated in CO2 enriched conditions at 37°C. Figure 1 shows the oily appearance of M. bovis, which typically take 5–10 days to become apparent (Parker et al, 2018). For these reasons, farms using on-farm culture are unlikely to detect Mycoplasma spp. as any growth is unlikely to be visible on blood agar at 24 hours (Leimbach and Krömker, 2018).

Clinical cases often shed intermittently, and to increase sensitivity it is recommended to sample multiple animals from an outbreak, or the same animal over multiple time points (Biddle et al, 2003; Parker et al, 2018). In the absence of other major pathogens, a Mycoplasma spp. culture positive from a cow with recurrent mastitis is highly likely to be a true positive. It should be noted that freezing reduces the rate of recovery of Mycoplasma spp. by around 90% (Boonyayatra et al, 2010). For this reason fresh milk should be submitted wherever possible.

Polymerase chain reaction

PCR offers a more rapid diagnosis than bacteriological culture, with results typically produced within 24 hours. The majority of publications focus on diagnosis of M. bovis and many laboratories only offer PCR testing for this species. Test sensitivity is similar to culture, but this test will not identify other Mycoplasma spp. (Cai et al, 2005; Rossetti et al, 2010). Some laboratories offer multiplex PCR or denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis (DGGE), which will detect other species of Mycoplasma spp., however these tests are less well validated in milk. Multiplex approaches usually have high sensitivity to detect M. bovis, however can lack specificity to differentiate other Mycoplasma spp. (McAuliffe et al, 2003; Boonyayatra et al, 2012).

It should be noted that PCR will detect both viable and non-viable Mycoplasma spp. The significance of a culture negative, PCR positive sample is unclear as it may reflect non-viable Mycoplasma spp. that were not causal (Britten, 2012). However, where samples have been collected and frozen, PCR may be a more reliable test for Mycoplasma spp. than culture.

Antibody ELISA

Antibody ELISA testing is commercially available for M. bovis, and can be run on serum or milk. A positive result indicates exposure, but not necessarily infection status or shedding. Following infection, seroconversion typically takes 2–3 weeks (Wawegama et al, 2014), which means that antibodies are usually present by the time Mycoplasma spp. infection is suspected. Antibody testing is highly sensitive (Hazelton et al, 2018), and more useful in chronically infected animals, where recovery of Mycoplasma spp. by culture or PCR can be difficult (Nicholas and Ayling, 2003).

Although the duration of immunity is unclear, antibody levels drop over time (Nicholas and Ayling, 2003; Petersen et al, 2018). For this reason, sensitivity is likely to be highest within months (not years) of infection (Nicholas and Ayling, 2003). It is the preferred test for bought in animals, if all animals in a group test negative for antibodies, then circulating infection is unlikely.

Herd level testing

Culture, PCR and antibody testing are all validated on bulk milk samples. Bacteriological culture and PCR have similar sensitivity for detecting Mycoplasma spp. in bulk milk (Justice-Allen et al, 2011; Adkins and Middleton, 2018). However, because of their widespread environmental presence, the isolation of a Mycoplasma spp. (or genetic material) is not necessarily diagnostic. It has been suggested that antibodies against M. bovis are likely to be more clinically significant than a positive culture or PCR, because they prove infection (Nicholas and Ayling, 2003).

A large-scale study compared antibody and PCR testing of bulk milk samples from 3437 dairy farms in Denmark (Nielsen et al, 2015). The authors concluded that antibody testing of bulk milk had higher sensitivity and specificity than PCR. The most frequently isolated Mycoplasma spp. in bulk tank samples is M. bovis, however coinfection with different Mycoplasma spp. is common (Justice-Allen et al, 2011). For this reason, antibody testing should be backed up with bulk tank culture or multiplex PCR to maximise sensitivity (Parker et al, 2017).

Surveillance

There is currently no national surveillance scheme in the UK, and as such the proportion of infected farms is unknown. In the Danish study described above, the prevalence of infected herds was estimated at 7.2% by ELISA and 1.6% by PCR (Nielsen et al, 2015). Other studies in mainland Europe have estimated the prevalence to be between 0–3% (Arcangioli et al, 2011; Passchyn et al, 2012; Pinho et al, 2013).

It should be noted that given the sensitivity and specificity reported by Nielsen et al (2015), there are likely to be a large number of farms testing positive for Mycoplasma spp. that do not have the disease (i.e. false positives). Table 1 shows how the positive and negative predictive values change with expected prevalence. The lower the expected prevalence, the higher the risk of a false positive. As a result of a low positive predictive value, general screening of herds is not an effective surveillance strategy. Instead, veterinary surgeons should only be using bulk tank investigations on farms that match the criteria in Box 1, in these farms the expected prevalence is likely to be higher and the reliability of a positive result will be improved.

Table 1. Effect of population prevalence on positive and negative predictive values of Mycoplasma bovis antibody testing, based on sensitivity (60.4%) and specificity (97.3%) (Nielsen et al, 2015)

| Expected prevalence | Positive predictive value | Negative predictive value |

|---|---|---|

| 1% | 18% | >99% |

| 2% | 31% | 99% |

| 5% | 54% | 98% |

| 10% | 71% | 96% |

Conclusion

For identifying M. bovis, bacteriological culture and PCR are likely to offer similar sensitivity. PCR tests yield results more quickly however have poorer sensitivity for detecting some other Mycoplasma spp. Bulk milk antibody testing is highly sensitive for M. bovis exposure, however it is not available for other Mycoplasma spp. Therefore, for general Mycoplasma spp. investigation, bacteriological culture remains the gold standard. It should be noted that all Mycoplasma spp. tests lack sensitivity to detect other more common causes of recurrent mastitis (shown in Box 2). For this reason, individual cow milk samples should be submitted for routine bacteriological culture according to standards defined by the National Mastitis Council (Adkins et al, 2017). Growth of any major pathogen in a sample from a cow with clinical mastitis should be considered diagnostic.

KEY POINTS

- General screening tests are likely to result in more false positives than true positives.

- Mycoplasma spp. investigations should be reserved for farms with the symptoms shown in Box 1, and where other causes of recurrent mastitis (Box 2) have been ruled out.

- Bacteriological culture of fresh milk is the most accurate way of identifying Mycoplasma s pp. in symptomatic cattle.

- Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing may be more useful in samples that have previously been frozen.

- Antibody testing may be more useful in chronically infected animals, or in pre-purchase testing.

- When investigating a suspected herd outbreak, a combination of tests is likely to maximise sensitivity.

- The most sensitive test for identifying herd Mycoplasma bovis exposure is an antibody enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) on bulk milk. This should be complemented with bulk tank culture or PCR to identify other Mycoplasma spp. present.