Hygiene has been recognised as a key factor for raising healthy calves (Klein-Jöbstl et al, 2014). Good hygiene management is a key element in minimising enteric disease risk in calves as it reduces their exposure to pathogens. Both colostrum and milk (or milk replacer) are key sources of contamination for calves.

The bacterial contamination of colostrum has been linked to a disruption in the absorption of immunoglobulins, leading to the failure of passive immunity transfer (Fecteau et al, 2002; Johnson et al, 2007) and thus, an increase in calf morbidity and mortality (Armengol and Fraile, 2016). In addition, increased levels of bacterial contamination in feeding systems for both milk and milk replacers are associated with higher morbidity rates, including depression and fever (Jorgensen et al, 2017).

Therefore, the feeding equipment of pre-weaned calves, which can be a source of contamination of colostrum and milk (or milk replacer), must be kept as clean as possible (Johnson et al, 2007; Armengol and Fraile, 2016) and veterinarians have an important role in advising their clients on how to do this (Heinemann et al, 2021).

Insufficient or irregular cleaning is a common issue in calf-rearing. Implementing effective cleaning and management strategies is crucial for disease prevention, as it prevents the transmission of infectious agents (Barry et al, 2019).

Poor calf feeding hygiene

Although management issues, such as uncleanliness, contribute to increased rates of diarrhoea (Appleby et al, 2001; Jasper and Weary, 2002), there is still a significant variation in hygiene practices on the farm level.

Hyde et al (2020) identified that bacterial contamination of colostrum most likely originated from the milking machine, collection buckets and feeding equipment. This is partly a result of the significant variation in cleansing practices observed on farms and a failure to adhere to some simple key principles. Similar variations have also been noted regarding the management of milk feeding in interviews conducted with farmers and advisors by Palczynski et al (2020). Good hygiene practices for milk feed preparation were prioritised to varying degrees on farms in the UK. Some farmers diligently disinfected equipment between feeding each calf or pen, while others did not. This lack of prioritisation sometimes stemmed from the pessimistic belief that hygiene was ineffective in controlling diseases. is this a double space? Additionally, some farmers believed that sterilisation could hinder immunity development.

These variations in procedures on farms, along with the erroneous beliefs around the importance of hygiene, highlight the need for veterinarians to engage with their clients on this topic and provide practical guidance.

Understanding current practices

The significance of hygiene should ideally be integrated into regular conversations about calf management on farms. However, in many cases, discussions regarding hygiene and current practices tend to arise only during a disease investigation prompted by a specific health issue or performance concern. To provide appropriate advice, it is essential to have a comprehensive understanding of the farm's situation.

For farms that calve animals and feed colostrum, hygiene assessment should begin with the collection and storage of the colostrum. It should then cover how the colostrum is fed to the calves, as well as all equipment used for preparing and administering subsequent milk feeds.

For calf rearers, the focus will be on all the equipment used in the preparation and delivery of milk feeds. For all farms, it is important not to overlook the equipment that is only used occasionally, such as stomach tubes or bottles and teats for sick calves. These items are used on the highest-risk animals and can often be forgotten during the regular cleaning regime.

It is essential to ask open-ended questions to ensure that the investigation provides a complete picture of what happens at the calf level. Simply asking, ‘Is your feeding equipment regularly cleaned?’ often leads to a quick positive response that gives no insight into the frequency or the process of cleaning. Instead, it is important to dig into the details of what happens and when.

To ensure proper procedures, veterinarians need to clarify the frequency of cleaning, the appropriate water temperature and any chemicals used along with their concentrations. Additionally, it is essential to communicate with everyone involved in calf feeding, as variations in practices among team members are common.

An open discussion about cleaning protocols can highlight significant inconsistencies among team members. It can also identify straightforward areas for improvement. This dialogue gives the veterinary surgeon a chance to establish a standard operating protocol for the entire farm.

Table 1 presents an overview of the key steps involved in cleaning calf feeding equipment. For any protocol to be effectively implemented, the team must have the appropriate infrastructure and equipment. Making the cleaning process easier, increasest he likelihood of this being done correctly. Inadequate setups and a lack of essential equipment are common barriers many farmers encounter, hindering the adoption of good hygiene practices (Palczynski et al, 2020).

| Calf feeding equipment cleaning protocol |

|---|

| Rinse using warm water (approx. 32-38oC), rinse dirt and milk residues off both the inside and the outside of the feeding equipment. Do not use hot water at this stage as that will cause the fat and protein to stick to the equipment. |

| Soak equipment in hot water (54-57°C) with a chlorinated alkaline detergent. Soak for at least 20-30 minutes. |

| Scrub ¬using a brush, clean all surfaces to loosen remaining residues. |

| Wash all of the feeding equipment in HOT water (at least 50°C) to remove any remaining residues. |

| Rinse Again - Rinse the inside and outside of feeding equipment again using an acid sanitiser. This lowers the surface pH and makes it very difficult for any remaining bacteria to thrive. |

| Dry - Allow the equipment to drain and dry before using again. Equipment should be hung up or left on drying racks to dry thoroughly. Avoid stacking buckets inside each other and certainly do not place feeding equipment upside down on a concrete floor because this will inhibit proper drying and drainage and provide bacteria with the perfect environment to multiply. |

The team needs sufficient water supply at the appropriate temperature, the right chemicals, and the tools to measure these chemicals to the correct concentration. Additionally, they require cleaning equipment such as brushes and a well-designed wash trough with good drainage. It is also essential to have areas to hang items for draining and drying, keeping them off the floor and away from potential sources of contamination after cleaning (Figure 1).

Visual assessment

The provision of an objective assessment of equipment cleanliness is a key step in engaging with clients on the important topic of hygiene and being able to assess the impact of changes in management procedures and protocols. Visual inspection of feeding equipment using scoring systems such as the one proposed by Renaud (2017) and outlined in Table 2 can help provide a rapid, low-cost objective assessment and can be used to highlight specific areas that need better attention. They are often useful during initial visits or disease investigations where they can be used to highlight equipment that requires cleaning (Figure 2).

| Score | Overall hygiene score | Milk/colostrum | Faecal material |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Feeding equipment is visibly clean (ie no faecal material or milk/colostrum debris residue). | No milk/colostrum debris residue is visible. | No faecal material is visible. |

| 2 | Trace amounts of manure, milk/colostrum residue, or both, are visible. | Trace amounts of milk/colostrum residue are visible. | Trace amounts of manure residue are visible. |

| 3 | Manure, milk/colostrum residue, or both, is clearly visible. | Milk/colostrum residue is clearly visible. | Manure is clearly visible. |

| 4 | Manure contamination, milk/colostrum residue, or both, is extensive. | Milk/colostrum residue is extensive. | Manure contamination is extensive. |

Visual assessments can be used as a component of routine monitoring programmes to quickly assess the condition of feeding equipment during each visit. The objective should always be to achieve a visual hygiene score of 1 immediately after the cleaning process and right before the equipment is used again.

When inspecting feeding equipment, it is also important to pay attention to its physical state. The surface quality of feeding equipment can also influence the extent to which cleaning and disinfection remove organic matter and microorganisms (Heinemann et al, 2021). Surface damage, such as cracks or scratches, can be inaccessible to cleaning products or tools and can, therefore, provide protection to microorganisms. While great for drawing attention to dirty equipment, visual scoring systems are of limited use in assessing the effectiveness of cleaning practices, as they do not provide information on the level of bacterial contamination on visibly clean surfaces.

Bacteriology

Routine bacteriological testing of colostrum or milk fed to calves is relatively inexpensive and straightforward. It should be considered an essential part of a hygiene monitoring programme or included in investigations of enteric diseases in pre-weaned calves. Bacteriology is commonly regarded as the gold standard for detecting microbial contamination on surfaces (Renaud et al, 2017; Lindell et al, 2018). Directly swabbing feeding equipment allows veterinarians to identify the specific bacteria present and quantify the total bacterial count and total coliform count (Malik et al, 2003; Willis et al, 2007).

Thresholds have previously been suggested for classifying bacterial contamination, specifically for total bacterial counts at over 100 000 colony-forming units (cfu) per millilitre, and for coliform counts at over 10 000 cfu/ml (McGuirk, 2004). These thresholds are useful for benchmarking farms and providing context for individual farm results. However, it is important to note that studies have shown it is possible to achieve very low colony counts on feeding equipment.

In a study by Hyde et al (2020), 41' of the samples collected from feeding equipment had a colony count (CC) of zero, indicating that achieving a count of 0 cfu/ml is a realistic target for farms in the UK. However, a significant challenge of bacteriological testing is that it requires a step for bacterial growth and quantification. This means that results cannot be obtained quickly, which may limit the application and engagement with this testing method on farms.

Adenosine triphosphate monitoring

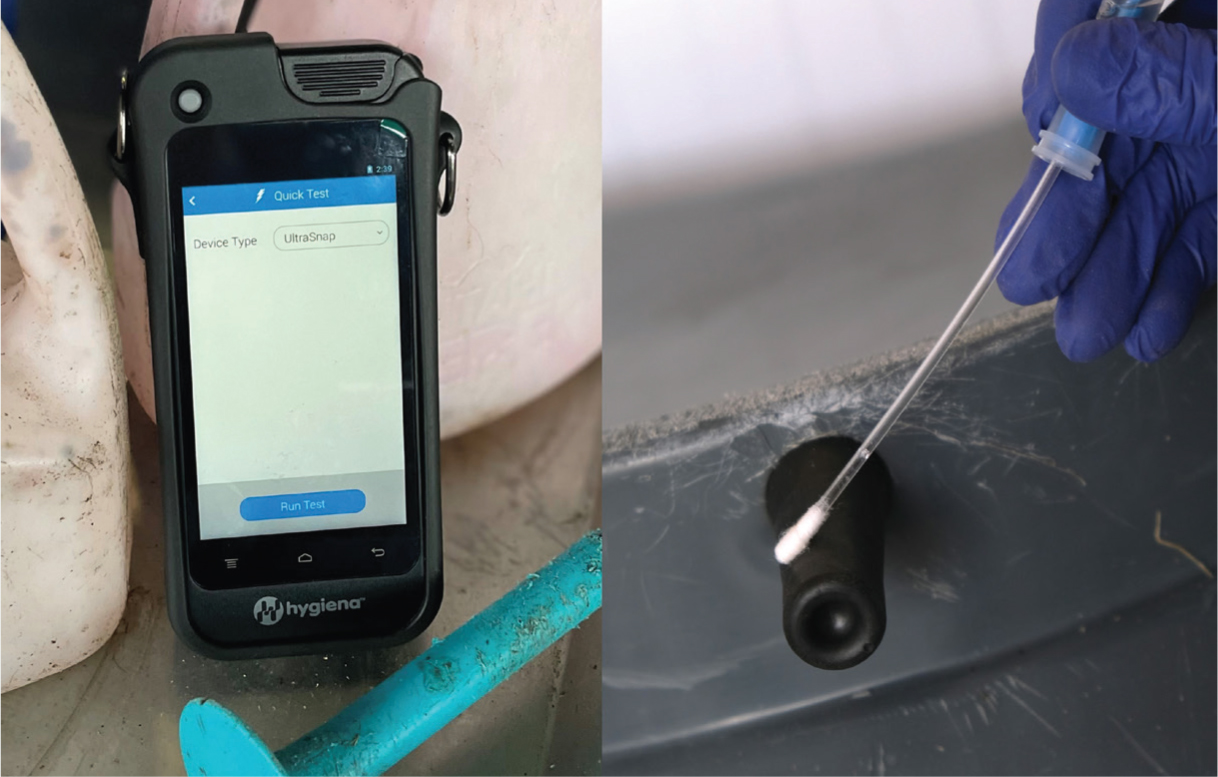

In the last few years, the rapid assessment of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) found on different surfaces has begun to be used on farms as an indirect tool for quantifying bacterial contamination (Mildenhall and Rankin, 2020). The monitoring of ATP is already widely used as a standard approach in the medical and food industries, where ATP, because of bacterial activity on the sampled surface, is quantified using a bioluminescence assay and is generally tested in a portable device (Figure 3).

The results are displayed in relative light units (RLUs) just a few seconds after the swabbed material comes into contact with luciferase, an enzyme that produces light through a chemical reaction. This means that an objective result is available within 30 seconds of sampling a surface. Such a quick turnaround allows for immediate discussions about the results, which enhances client engagement. Additionally, the low cost of swabs makes it feasible to incorporate regular hygiene assessments into calf health monitoring programmes.

Recent studies have examined the standardisation of testing methodologies (Chancy et al, 2023; Van Driessche et al, 2023) and have described the variations observed on different surfaces, as well as the differences among various commercially available swabs. Chancy et al (2023) propose a standardised sampling approach that depends on the type of surface being sampled.

For flat surfaces, such as buckets, the swabbing technique should follow the standard operating procedures recommended by the swab manufacturers. This aims to collect a sample from a 100 cm2 area, which is equivalent to a 10 cm × 10 cm square. When swabbing teats, start at the orifice and move back and forth along the entire length of the teat to ensure proper sampling.

For tubular equipment, such as esophageal feeders or tubes from automatic milk feeders, pour 15 ml of sterile physiological saline down the tube and collect it in a sterile container. This sample can then be used for luminometry testing.

In situations where a thorough cleaning process is followed, ATP measurements can be taken from feeding equipment located below 100 RLU. However, if there are issues with the cleaning process, ATP measurements can easily exceed 3000 RLU. Based on the author's experience, swabbing equipment at each stage of the feeding process can help identify steps where cleaning is inadequate. It is important to remember that the luminometer detects not only microbial ATP but also all types of ATP, including that from normal eukaryotic cells and residues from milk or colostrum. Therefore, luminometry should be conducted after the cleaning process has been completed.

Ultimately, a high ATP measurement, shown as an increase in the measured RLU, means that the feeding equipment and cleaning procedures are not optimal.

Conclusions

Young calves are highly vulnerable to disease as their immune systemsare still developing and they face numerous stressors during the first few weeks of life (Hulbert, 2016). Therefore, it is crucial to minimise their exposure to disease-causing organisms through proper hygiene practices as part of calf management (Heinemann, 2021). Numerous studies (Hyde, 2020; Palczynski, 2020) have highlighted the significant variation in hygiene practices currently observed on farms in the UK (Hyde, 2020; Palczynski, 2020). his variation presents an opportunity for veterinary surgeons to engage with their clients about the importance of hygiene in all aspects of calf rearingincluding their health, welfare and performance.

Veterinary surgeons need to provide advice, guidance and monitoring services to ensure that this essential aspect of calf management is effectively addressed.