The Schmallenberg virus (SBV) is an orthobunyavirus belonging to the Simbu serogroup (Endalew et al, 2019). It was first identified in late 2011 in cattle in Germany, showing clinical signs such as reduced milk yield and fever (Alarcon et al, 2013). Shortly thereafter, SBV caused an outbreak of foetal abnormalities and abortion storms in sheep, cattle and goats across Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands (Scott, 2012). Within three months of the initial outbreak, SBV spread to England, with all the southernmost counties reporting cases between 2012 and 2013 (Stokes et al, 2016). The virus is transmitted by the insect vector Culicoides spp, which can also lead to vertical transmission to fetuses. Currently, SBV is not considered zoonotic; however, the possibility cannot be completely ruled out (Alarcon et al, 2013).

The period of highest susceptibility to infection is between days 25 and 50 of gestation. While adult sheep typically do not show any symptoms, transplacental transmission in pregnant sheep can have significant clinical consequences. Affected lambs are born with bent limbs and fixed joints as a result of brain and spinal cord abnormalities caused by SBV infection (Scott, 2012). By 2014, SBV had impacted 25' of farms in a study conducted across Britain, leading to notable lamb and ewe mortality that created significant burdens on animal welfare, financial performance and the emotional well-being of farmers (Doceul, 2014).

Transmission

SBV is transmitted by the insect vector Culicoides, which can result in vertical transmission in utero (Alarcon et al, 2013). The virus was first identified through isolation from two distinct species of Culicoides: Culicoides obsoletus and Culicoides dewulfi. This supports the notion that the transmission of the virus is facilitated by an insect vector (Roger, 2015).

SBV is harboured within infectious Culicoides and transmitted to adult sheep via bites, leading to infection and subsequent viraemia. Sheep previously infected with SBV build long-term protective immunity. However, if a naive adult animal is infected during the susceptible stage of gestation, the virus will cross the placenta and, as a result, infect the fetus in addition to the ewe (Collins et al, 2019).

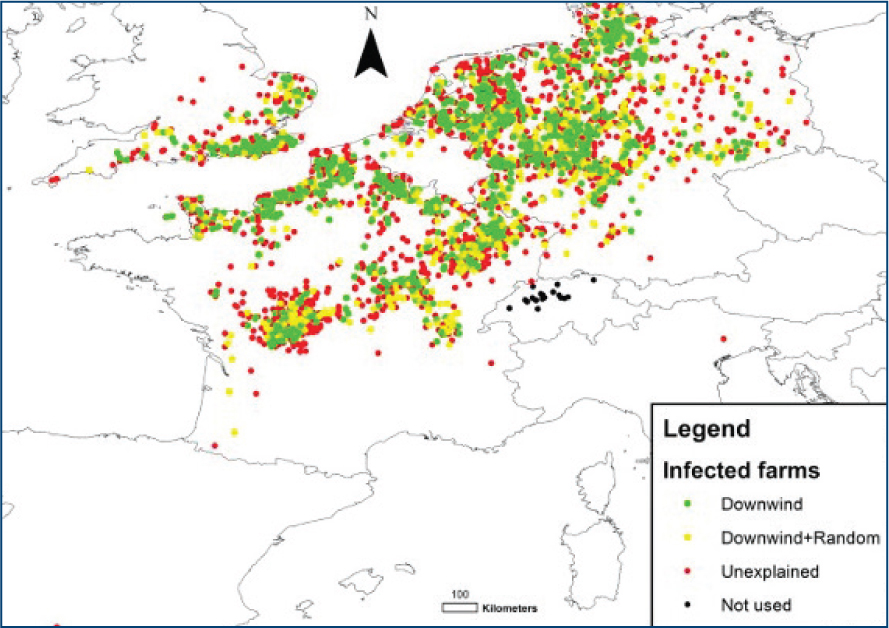

The maximum spread of SBV via Culicoides is limited to 200 km at a time and is heavily influenced by wind direction as Culicoides are wind-borne midges (Sedda and Rogers, 2013).

Models, such as Figure 1, analysing the transmission dynamics of SBV infection indicate that 62' of cases in England arise from farms located downwind of other infected sites. The remaining 38' are attributed to a combination of wind direction and other stochastic factors (Sedda and Rogers, 2013).

Vertical transmission refers to the transfer of viruses from parent to offspring, specifically the transplacental transmission of SBV (Fermin, 2018). This occurs during the first trimester of pregnancy and into the early second trimester. When infection is passed from the dam to the fetus, it can result in abortion, stillbirth or fetal abnormalities (Endalew et al, 2019). SBV can cross the placenta during the most vulnerable stage of pregnancy, between days 25 and 50 in sheep. Fetuses older than 50 days of gestation are generally able to clear the virus (Scott, 2012).

The virus has been observed to tolerate various climates, as evidenced by the confirmed presence of SBV in Italy and Norway. The Culicoides vector, which transmits the virus, is most abundant from April to October, with peak activity occurring between July and September (Stavrou et al, 2017). SBV has overwintering properties that allow it to survive in the vector during winter months when Culicoides activity is low; however, the exact mechanism behind this process is not yet fully understood (Collins et al, 2019).

No zoonotic effects have been observed from the virus, and there is no evidence suggesting animal-to-animal transmission (Roger, 2015). Experimental nasal inoculation of sheep did not result in SBV RNA viremia, indicating that the animals remained seronegative (Collins et al, 2019).

Clinical signs

Adult sheep generally show no symptoms. Although a direct relationship has not been established, fever, diarrhoea and decreased milk production have been reported in adult sheep that test positive for SBV (Endalew et al, 2019).

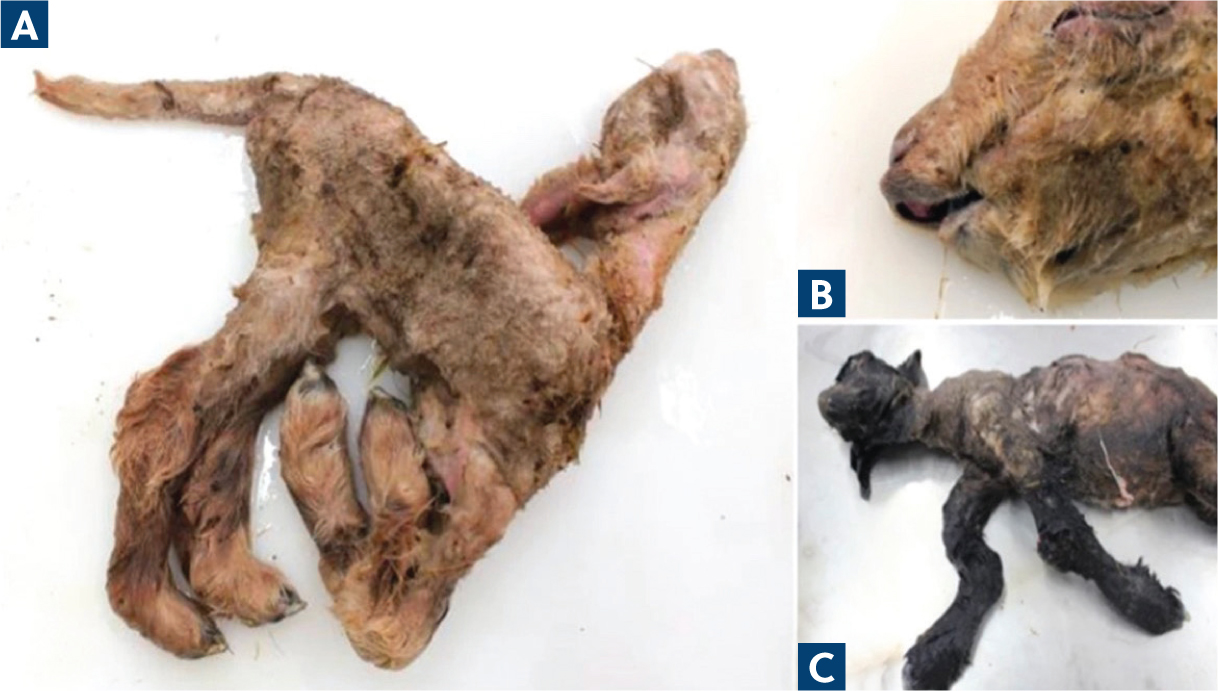

The main concern is the vertical transmission of SBV between days 25 and 50 of gestation, leading to lambs being born infected (Scott, 2012). Suggestive clinical signs of SBV in neonates include arthrogryposis, torticollis, scoliosis and hypoplasia of the cerebrum, cerebellum and spinal cord (Roger, 2015). The primary indication of SBV in affected lambs is bent limbs and fixed joints, which may affect all limbs and the spine or only some; these clinical sings are displayed in Figure 2 (Scott, 2012).

Some animals are born with a normal appearance but exhibit ‘dummy’ neurological signs, such as blindness, ataxia and an inability to suck. The severity of foetal abnormalities depends on the stage of gestation at which the dam was infected (Scott, 2012). In multiple births, such as twins, abnormalities are not always uniform, meaning one lamb may show signs of malformation while the other is born healthy without clinical signs (Endalew et al, 2019).

In a study conducted into abnormalities in lambs at birth, it was found that 88' of flocks with confirmed SBV reported at least one lamb with one of the following abnormalities: twisted limbs, curved back or overshot jaw. The lamb mortality, including stillbirths and the lambs that died within one week of birth, was double on SBV-positive farms compared to SBV-negative farms (Harris et al, 2014).

Diagnosis

Adult sheep are typically asymptomatic, although cases have been recorded with pyrexia, diarrhoea and reduced milk yield. Transplacental transmission to neonates causes more prominent clinical signs, such as musculoskeletal deformities and hypoplasia of the cerebrum and cerebellum. As several other ruminant viruses can cause similar symptoms, a virological or serological diagnosis is required to confirm SBV definitively (Endalew et al, 2019).

SBV is an enveloped virus with a genome consisting of ‘three negative-sense single-stranded RNA segments’, named according to their size: Small (S), Medium (M) and Large (L) (Collins et al, 2019).

A real-time reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction test (RT-qPCR) can be used to detect SBV RNA. Not all animals tested using the RT-qPCR were deemed positive after the detection of SBV RNA as the test can only suggest the presence of SBV RNA and not definitively determine subsequent infection. The detection of SBV genomic sequences in the umbilical cord, placental fluid, cerebrum, brain stem and spinal cord of deformed lambs can be used to confirm infection (Endalew et al, 2019). Several types of PCR tests have been developed to identify distinct segments of SBVs genome (S, M or L). The S segment-based assay is the most effective in terms of specificity and sensitivity (Collins et al, 2019).

The detection of SBV antibodies in adult sheep is a reliable method of viral detection because of the lack of clinical presentation and limited duration of viraemia (Collins et al, 2019). Two serological methods have been developed for the detection of SBV antibodies: virus neutralisation test (VNT) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). VNT is slower, thus only primarily used as a confirmatory test whereas ELISA is more affordable and quicker; however, false-positive results are common in areas with other Simbu serogroup viruses present. Additionally, it possesses a lower specificity and sensitivity than VNTs but is advantageous in its ability to detect anti-SBV antibodies in milk (Endalew et al, 2019).

Treatment and prevention

There is no specific treatment for SBV-infected sheep (Collins et al, 2019).

Several vaccines were made available in January 2018 (Scott, 2012) which effectively prevented viraemia and clinical signs, including foetal abnormalities and stillbirths. Three commercial vaccines were made available: Zulvac SBV (Zoetis), Bovilis SBV (MSD Animal Health) and SBVvax (Merial) (Endalew et al, 2019). However, subsequent data have shown that previously vaccinated animals are not necessarily protected from repeated infections. A study in Scotland conducted by Bessell in 2014 demonstrated that the use of the vaccine was optimised when only using it in high-risk areas. The same study also showed that in areas with a higher mean temperature (meaning increased number of Culicoides) the impact of the vaccine was much greater. After initial uptake of the vaccines post-release, the demand promptly declined leading to all three vaccines being taken off the market because of a negative economic impact on the vaccine producers (Collins et al, 2019).

A variety of supplementary options to decrease SBVs effects have been discussed and implemented. Primarily the introduction of insecticide usage to reduce Culicoides populations; however, this has proven to be ineffective on larger scales. The most practical solution presented is to postpone breeding until later in the season to reduce the effect of SBV. However, in years with frosts in later months, Culicoides numbers can remain high until October because of the colder climate postponing the Culicoides season until later in the year (Scott, 2012).

The exposure of youngstock to Culicoides could result in natural SBV infection giving the lamb long-lasting immunity. Exposing lambs to the vectors before they breed could assist in reducing the number of ewes getting infected during pregnancy, thus causing less vertical transmission to fetuses. However, this method is unlikely to be highly effective on its own, meaning a combination of prevention methods should be used to reduce the risk of SBV infection in sheep (Collins et al, 2019).

Economic impact

In confirmed SBV flocks, farmers have described an increase in repeat oestrus and larger proportions of barren ewes, resulting in fewer offspring being born (Harris et al, 2014). The leading costs associated with SBV infection are replacing ewes culled or died post-SBV infection and lost revenue from having fewer finished lambs (Alarcon et al, 2013). A 2013 study conducted in Ireland reported a 10' reduction in the weaning rate (weaning rate is the number of lambs weaned compared to the number of ewes that were served in the 2012 breeding season) in flocks with confirmed SBV when directly compared to SBV negative flocks (Barrett et al, 2015). Additionally, SBV infection significantly reduces fertility rates in sheep flocks. The interferon IFN-tau is the primary pregnancy recognition signal in ruminants and studies have described that the NSs protein of SBV has a major impact on the inhibition of the interferon's production. This inhibition is largely responsible for the increase in early embryonic death and subsequent repeat oestrus (Collins et al, 2019).

An investigation into the impact of SBV on the gross margins of farms was conducted in 2014. The gross margin was expressed as £/ewe/year for each type of farm and the results were divided into three categories: not affected, slightly affected and highly affected by SBV. In a farm highly affected by SBV, a 43' reduction was observed in the gross margin of lowland spring lambing flocks and a 76' decrease in the gross margin of upland spring lambing flocks. Furthermore, on slightly affected farms, a 14' and 25' decrease was seen in the gross margins of Lowland Spring lambing flocks and Upland spring lambing flocks, respectively (Alarcon et al, 2013).

Similarly, a UK survey measured the level of impact of SBV during the 2016-2017 lambing season. The survey found that positive SBV flocks had higher neonatal lamb mortality, dystocia and associated ewe deaths. The survey also demonstrated that SBV confirmed farms have a decreased financial performance and a negative impact on the animal's welfare. The farmers also stated that SBV had a negative impact on their personal wellbeing (Collins et al, 2019).

Discussion

Since the identification and isolation of SBV in 2011, it is evident that substantial research has occurred regarding the transmission of the virus with numerous papers available outlining the pattern and ability of the Culicoidesled transmission. Similarly, there was a vast amount of information available about the clinical presentation of SBV. Despite this, it seems there is a gap in the literature regarding the diagnostics of the disease with limited numbers of reliable studies available, which demonstrate a great depth of knowledge of the topic.

There was also a lack of papers discussing the current outbreak of SBV in the UK, during the 2023/2024 lambing season. There were anecdotal reports on the subject, but these were unreliable and lacked scientific evidence to support their statements. Additionally, more research is needed to create a better understanding of the modern climates and populations of SBV.

The Alarcon et al (2013) survey used in this literature review was answered by 318 farmers, however only 215 of the responses were usable because of a lack of relevant answers. While the survey was aimed towards farmers who would be familiar with the virus, the use of online surveys increased the possibility of response bias, answer errors and survey fraud.

Most of the papers included in this review are taken from peer-reviewed veterinary journals and records thus increasing their reliability; however, many of the papers were written between 2013–2016 making the information included in the sources outdated and suggesting that more research should be done into SBV to obtain current and relevant information. Information from the NADIS database was also included in this review; this source is peer-reviewed by two veterinarians, increasing its credibility.

From this review, it can be concluded that there is a sufficient gap in readily accessible data regarding SBV diagnostics, the herd immunity status of UK sheep flocks and the zoonotic potential, which is paramount to allow better protection of farmers and veterinarians.

Conclusions

Based on the literature reviewed for this paper, SBV is a viral disease that primarily affects ruminants, with adult sheep presenting asymptomatically. The impacts are largely seen in the musculoskeletal abnormalities of neonates alongside the devastating losses caused by SBV-induced abortion storms. SBV is a relatively novel disease as it was only discovered in 2011 and although at present there is no evidence indicating the zoonotic potential of the virus, more research is required in this area. Additionally, despite the extensively documented relatively short and specific susceptibility window of the transmissibility to fetuses, there is a lack of accessible research into the effects of the virus on both dam and fetus outside of this. For the benefit of UK farmers, it should be recommended that more data are gathered regarding the economic losses and its subsequent mental impacts. Additionally, diagnostic tests and SBV trend monitoring should be more accessible and actively encouraged.