The IVC Evidensia Sheep Caesarean and Lambing Audit was produced by the primary author and approved by the Sheep Clinical Working Group (SCWG) with the survey taking the form of an online survey through Microsoft Forms. Questions recorded user details, patient details, presentations, treatments and results of intervention. Outcomes-related questions captured data relating to ewe and lamb(s) at 1- and 7-days post procedure, where relevant. Copies of the questions can be supplied on request.

The survey ran from 30th December 2021 until 31st May 2022, and was available through hyperlink, bitlink and QR Code circulated among veterinary practices in the group. Twenty-one practices provided data from 209 procedures within this 5-month period.

Results

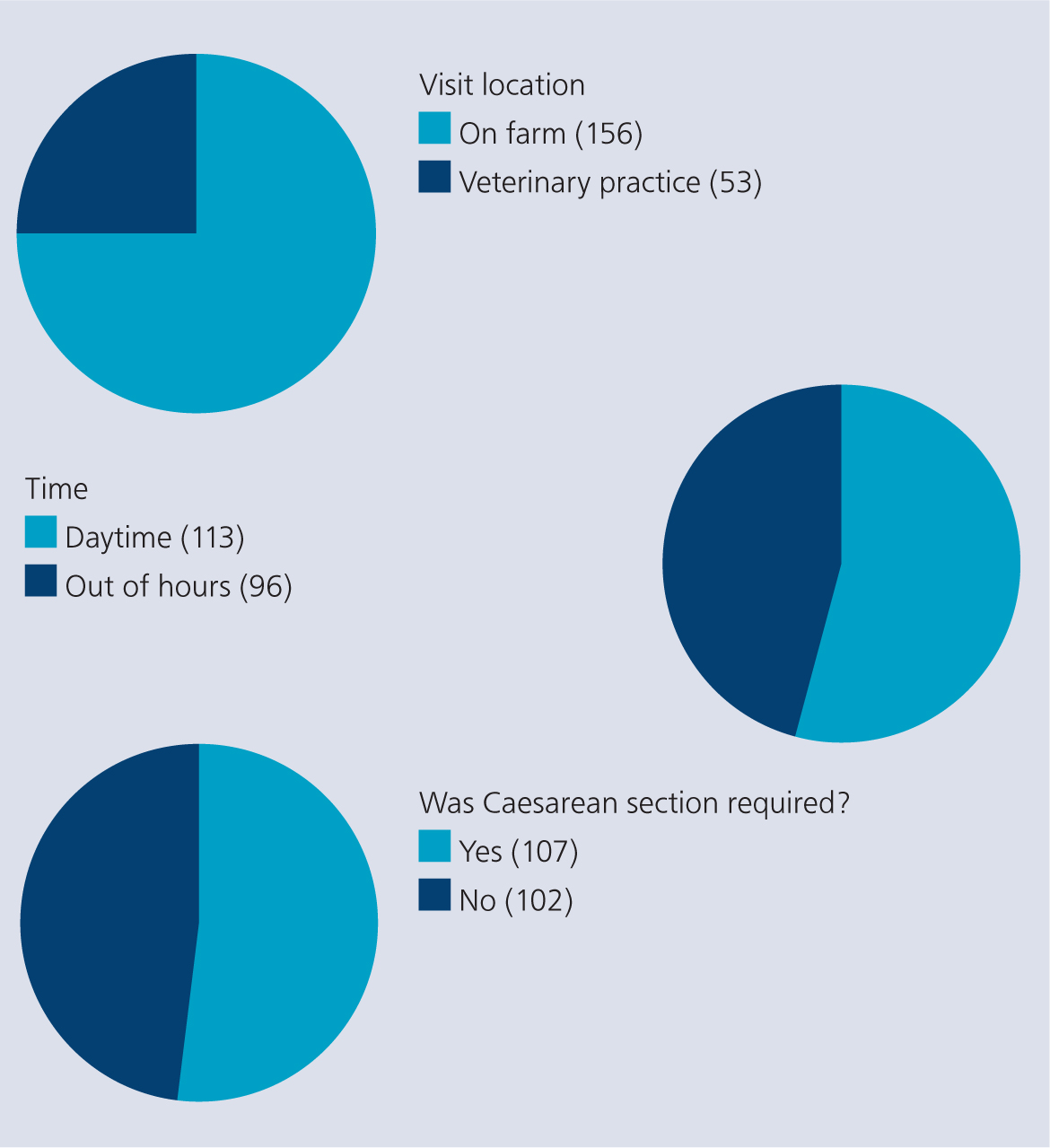

Data from 209 procedures and the associated postoperative checks were recorded through the survey, with the following splits between location, time and intervention required (Figure 1).

Findings were summarised and split into the following categories:

- Initial overview of results/broad trends

- Infection control

- Antibiotic use and selection

- Analgesia and anaesthesia.

Initial overview of results/broad trends

A high proportion (51%) of the ewes presented to respondents for obstetrical difficulties required a Caesarean section, with 13% of these being elective or where the attending veterinary surgeon did not attempt vaginal delivery first.

For assisted vaginal deliveries (lambings) (102 responses) 86.2% of ewes were alive, bright, alert, and responsive at 7 days post procedure, with 85% of lambs delivered alive being alive at 7 days post procedure, representing 74% of lambs delivered vaginally.

For Caesarean sections (107 responses) 94.8% of ewes were alive, bright, alert and responsive at 7 days post procedure, with 78.1% of lambs delivered alive being alive at 7 days post procedure, representing 74.4% of lambs presented in utero.

61% of ewes presented had suitable colostrum available within the udder post procedure, 19.8% of respondents did not check and the remaining 19.2% of ewes were felt not to have sufficient, expressible colostrum immediately post procedure.

Patient data were broadly varied, however, Texel or Texel-cross ewes accounted for a significant proportion (37%) of cases, followed by North Country Mule (14%), Suffolk (13%) and Beltex (7%) breeds.

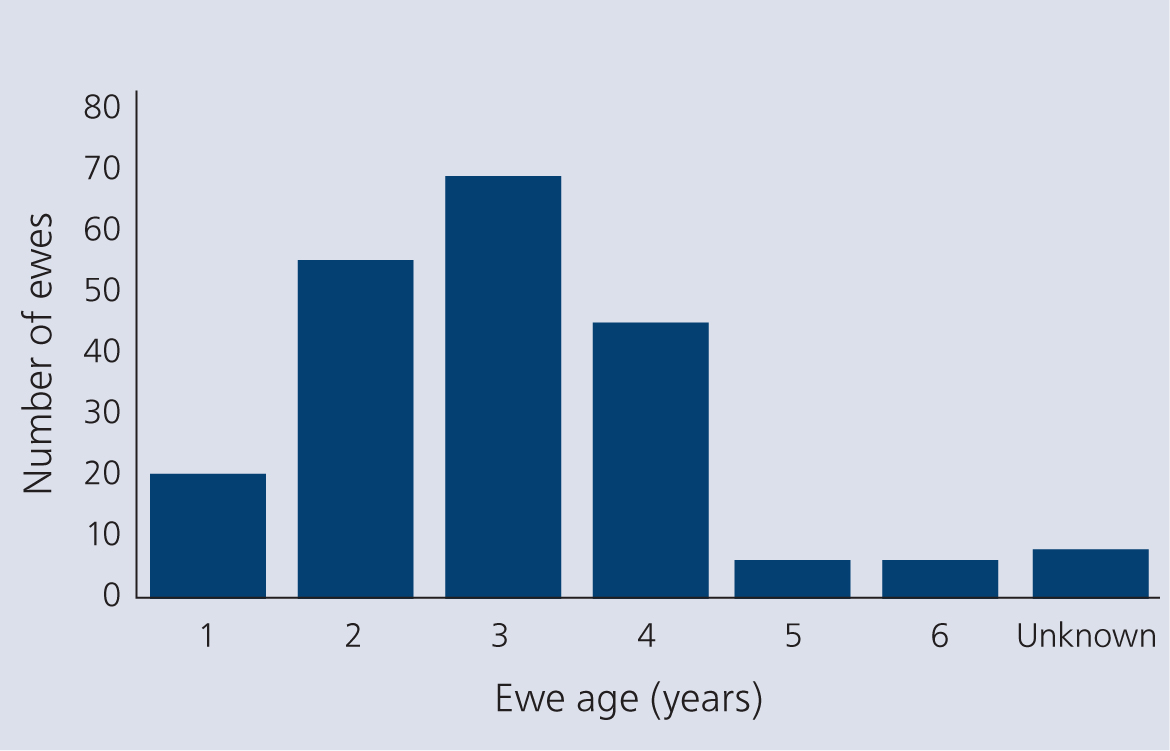

A wide variation of ages of ewes was observed (Figure 2); perhaps surprisingly shearlings were not overrepresented within the ewes presented, despite anecdotal beliefs among the farming community that shearlings require increased assistance or veterinary intervention.

Lambings

Data from 102 assisted vaginal deliveries (lambings) was recorded. 74% of lambs delivered did not require revival, and those that did were revived through an array of means including vigorous rubbing, nasal philtrum acupuncture, nasal stimulation with straw and Nimrod Redstart paste.

Vaginal tears were observed in 13% of ewes lambed and 18% of these required suturing. Ewes with vaginal tears that were sutured did not have an increased number of complications or negative outcomes 7 days post procedure compared with those with no vaginal tears or vaginal tears that did not require suturing. Only two ewes attended had uterine tears and one of these ewes died.

Caesarean sections

Data from 107 Caesarean sections were recorded. In terms of procedure there is a near total uniformity in surgical approach with 99% of respondents selecting the left paralumbar approach as described by Thorne and Jackson (2000). The only other approach used was the ventral or paramedian approach, which is more commonly used in Australia and New Zealand, however, a ‘Best BETS’ evidence-based veterinary medicine search run by the Centre for EBVM, University of Nottingham, found no difference in mortality between the two approaches from the evidence available (Downes and Dean, 2014).

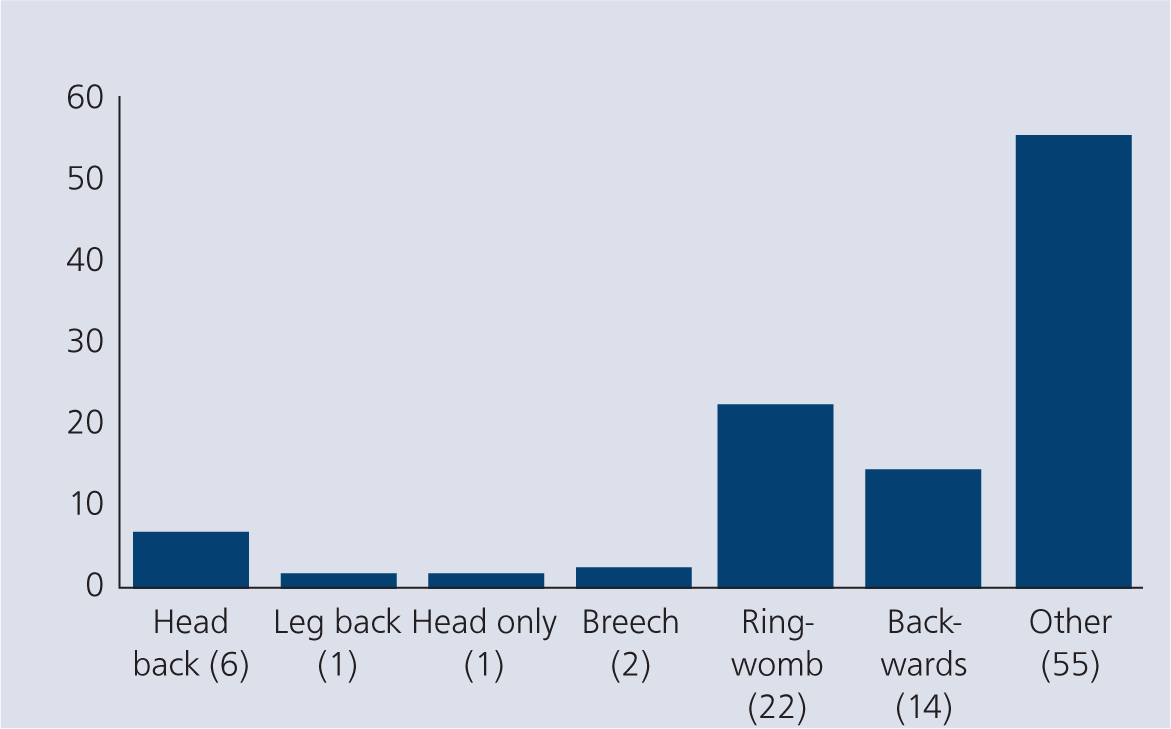

The presentation of the lambs at Caesarean section are shown in Figure 3 — 40 of the 55 cases described as ‘other’ were ‘normal presentation’ (i.e. head and two forelimbs), and the authors acknowledge that ‘normal presentation’ should have been an option for this multiple-choice option question. It can therefore be deduced that the majority of these ‘normal other’ presentations correlate to the abundance of ‘feto-maternal disproportion’ responses in Table 1.

Table 1. Reason for Caesarean section (Question 38)

| Reason for Caesarean section | Number of responses |

|---|---|

| Elective (farmer requested) | 14 |

| Feto-maternal disproportion | 52 |

| Inability to correct malpresentation | 3 |

| Ringwomb | 20 |

| Uterine tear | 0 |

| Other | 17 |

Infection control

Chlorhexidine was the most commonly used surgical scrub for both surgical site (84%) and surgeon (76%), followed by povidone iodine in both cases (16% patient, 18% surgeon), and 6% of surgeons reported using sterilium or other alcohol-based disinfectant (Sterilium Hand Based Disinfectant, Hartmann).

25% of respondents used sterile surgical gloves when performing Caesarean section compared with 87% of respondents using disposable gloves when assisting with a vaginal delivery. 38% of respondents used surgical drapes for Caesarean section.

Antibiotic use and selection

The most commonly used antibiotic was penicillin and dihydrostreptomycin (Pen+Strep, Norbrook Laboratories), followed by amoxicillin (Betamox LA, Norbrook Laboratories or Betamox 150, Norbrook Laboratories) (Table 2). No significant variation in outcomes (ewe survival at 1 and 7 days and surgical site complications) was reported between the products.

Table 2. Antibiotic Selection for Caesarean section

| Antibiotic product | Antibiotic | % | EMA category |

|---|---|---|---|

| Betamox 150, Norbrook Laboratories | Amoxicillin | 5.6 | D |

| Betamox LA, Norbrook Laboratories | Amoxicillin | 4.7 | D |

| Depocillin, MSD Animal Health | Procaine benzylpenicillin | 0.9 | D |

| Hymatil, Forte Healthcare | Tilmicosin | 12.1 | C |

| Pen&Strep, Norbrook Laboratories | Procaine penicillin & dihydrostreptomycin Sulfate | 63.6 | D & C |

| Pen&Strep and Hymatil | Procaine penicillin & dihydrostreptomycin & tilmicosin | 3.7 | D & C & C |

| Synulox, Zoetis (off licence) | Amoxicillin-Clavulanate | 0.9 | C |

| Trymox, Univet | Amoxicillin | 5.6 | D |

| Zactran, Boehringer Ingelheim | Gamithromycin | 0.9 | C |

| None | - | 1.9 | - |

EMA = European Medicines Agency

Table 2 also shows that European Medicines Agency (EMA) category C ‘caution’ antibiotics are favoured by respondents, with 81.3% of respondents using a category C antibiotic as their firstline choice.

8% of respondents reported to still be using intra-abdominal or intra-uterine antibiotics alongside systemic antibiotics, and no significant improvement in outcomes was observed in these cases.

Analgesia and anaesthesia

100% of ewes undergoing a Caesarean section received non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), and all respondents used meloxicam. Duration and dose varied among respondents between a single peri-operative injection and a longer course providing 5–6 days of action; the modal value was two injections 2 days apart.

26% of respondents administered an epidural for assisted vaginal delivery. As with those using an epidural for Caesarean section (10.3%), the majority of respondents used local anaesthetic only, however, for assisted vaginal delivery 25% of respondents used a ‘spiked’ epidural combination of local anaesthetic plus xylazine, something that was not reported in any of the epidurals used for Caesarean section. For pure local anaesthetic, volumes used ranged from 0.5–1.5 ml, and for ‘spiked’ epidurals, volumes ranged from 0.8 ml local anaesthetic plus 0.2ml xylazine to 1.5 ml local anaesthetic plus 0.2 ml xylazine

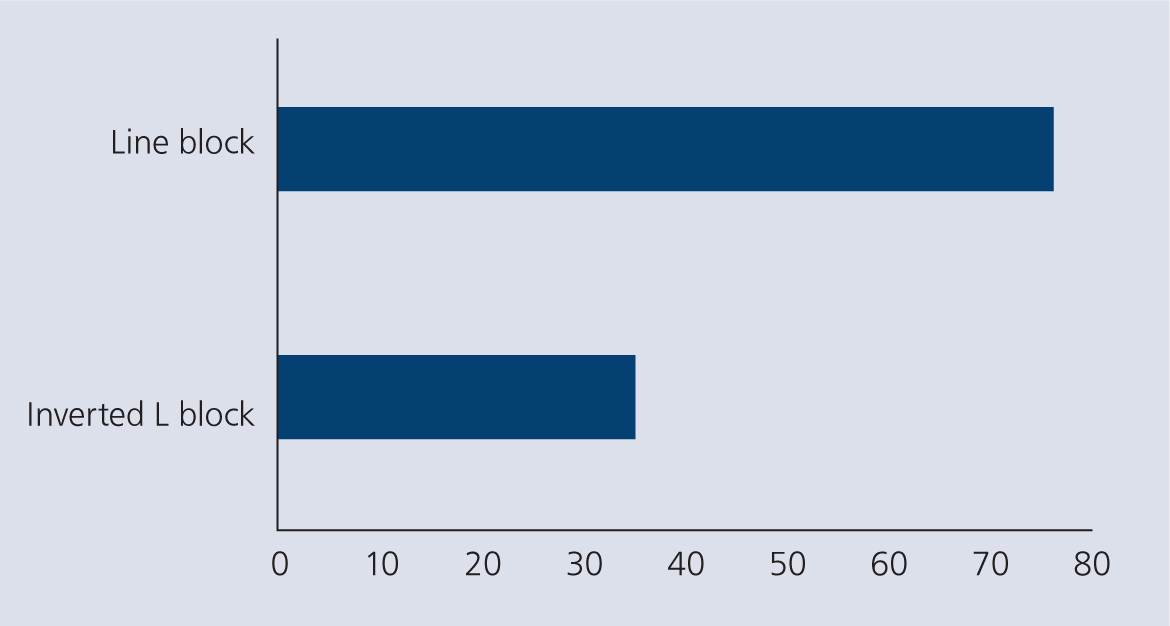

There was little variance in the ‘block’ used by respondents with 68.5% using a ‘line’ block, and 31.5% using the ‘inverted-L block’ (Figure 4). Unsurprisingly all respondents used products containing procaine plus adrenaline (Adrenacaine, Norbrook Laboratories; Procamidor Duo, Richter pharma; Pronestesic, FaTro) with variation in product mostly being a result of supply issues in the past 12 months. Both techniques are accepted, commonly used methods of loco-regional anaesthesia for ovine Caesarean section (Scott, 2015; Mueller, 2017; Phythian et al, 2019), and no significant variation in wound breakdown was observed by either technique.

Significant variation was observed when it came to the volume of local anaesthetic use with doses varying from 6 ml to 100 ml (Figure 4); the modal volume used was 60 ml and the mean was 50.46 ml. Respondents using the line block used on average 10.1 ml less local anaesthetic than those using an inverted-L technique (Figure 5).

Uterine relaxants and oxytocin

13% of respondents administered clenbuterol to aid with repositioning and/or vaginal delivery; there is currently no industry standard on clenbuterol dosage for small ruminants, which was reflected in the varying dosages given (2–5 ml, modal value 5 ml).

85% of respondents giving clenbuterol to relax the uterus gave intramuscular oxytocin post procedure to aid uterine involution, and overall 36% of lambings and 53% of Caesarean sections received oxytocin. A wide variation in volume administered was noted (range 1–4 ml), with the datasheet dosage being 2–10 iu/ewe equivalent to 0.2–1.0 ml of oxytocin-S 10 iu/ml (MSD). Across all cases, 75% of ewes had passed the placenta within 24 hours of veterinary intervention. When assessing the use of intramuscular oxytocin, 82% of cases that received intramuscular oxytocin during the procedure passed the placenta within 24 hours compared with 69% of ewes that did not receive intramuscular oxytocin. A 90% survival rate was observed in ewes that received oxytocin compared with 76% in ewes that did not receive oxytocin at the time of the procedure.

Discussion

There is an anecdotal belief that veterinary surgeons tend to be presented only with cases that represent significant obstetrical difficulty and, therefore, would be expected to have a lower success rate (where success is deemed as ewe and lambs all alive 7 days post procedure), or a higher surgical conversion requirement. Total number of ewes lambed by the farmers represented within this study were not recorded, and therefore it is not possible to draw comparisons between this study and Evans and Scott's (1999) study that found one in 21 ewes required human intervention at lambing (either farmer or veterinary), and that 6.7% of the ewes requiring human intervention were presented for veterinary assistance (assisted vaginal delivery or Caesarean section).

The outcomes of the lambings recorded in this audit are comparable to the 87.6% ewe survival and above the 44.7% lamb survival (of all possible lambs) reported in the 2013–14 study by Hawkins et al (2021), however it is worth noting that their study had a population of 203 vaginal delivery cases.

Likewise Caesarean section success rates were comparable to the 89.2% ewe survival and slightly above the 62.6% lamb survival (of all possible lambs) reported in the 2013–14 study by Hawkins et al (2021). However, it is worth noting that their study had a population of 205 Caesarean section patients.

In this audit, 18% of Caesarean sections seen were a result of ringwomb, however, very few respondents reported trying intramuscular denaverine hydrochloride (Sensiblex; Kela Health), which the manufacturer claims has efficacy in dilating the cervix in cases of ringwomb or incomplete cervical dilation, as well as providing ‘analgesia to the soft tissues of the birth canal’ (Health Products Regulatory Authority, 2017; Kela Health, 2017) and this may be something that practitioners within our group wish to consider for future years.

Infection control

The low number (6%) of practitioners using Sterilium (Sterilium Hand Based Disinfectant; Hartmann) or other alcohol-based hand rub suggests to the authors that farm animal practitioners are behind the trend in small animal and human surgery for the use of alcohol-based disinfectant for appropriate antisepsis for surgical procedures, as outlined by the Association for Perioperative Practice (AfPP). NHS UK and The AfPP both report that surgical rubbing with alcohol-based disinfectant and surgical scrubbing with chlorhexidine gluconate or povidone iodine can provide appropriate antisepsis for surgery (AfPP, 2022; National Health Service, 2022). More research is needed to assess the benefits of a surgical rub with alcohol-based disinfectant over a traditional surgical scrub using povidone iodine or chlorhexidine gluconate and the associated risk of using farm buckets and water to achieve surgical antisepsis.

Surprisingly, 75% of respondents do not currently use sterile surgical gloves when performing ovine Caesarean section. Surgical gloves protect the patient from infection by the surgeon, and the surgeon from exposure to irritants, e.g. placental tissues and uterine contents (Heathcote et al, 2007). Best practice for surgeon preparation and appropriate asepsis for abdominal surgery is the use of sterile surgical gloves (Thorne and Jackson, 2000; Welsh, 2015; Mueller, 2017; Phythian et al, 2019). Within human medicine the discussion has moved from whether to glove or not, to the benefits of double gloving over single gloving (Korniewicz and El-Masri, 2012). This suggests that production animal practitioners are potentially a long way behind human surgeons with respect to standards of surgical preparation. While the current survey found no impact relating to surgical site infections for gloving versus not gloving, respondents who did not use surgical gloves were more likely to report skin irritation within the first 24 hours post procedure (10% of respondents who did not use surgical gloves vs 0% who did). This high percentage of respondents not wearing surgical gloves was made more notable because of the direct contrast with the 87% response rate for the use of disposable gloves for lambing a ewe.

38% of respondents draped the patient, although further details regarding drape type were not collected. Use of a surgical drape reduces the risk of contamination of the surgical site, either from external/environmental contaminants (e.g. straw or wool) entering the abdominal cavity, or from abdominal viscera coming into contact with external ‘dirty’ surfaces (e.g. wool) when exteriorised as part of the procedure (Ludlow, 2015; Scott, 2015). In their review of the evidence Phythian et al (2019) described alternative, cost-effective approaches that could be used to create reusable drapes to reduce the cost to large animal practices compared with using high numbers of single use disposable drapes, including autoclaved tea towels or bags/wrapping material sterilised in a cold sterilising solution; consideration must be given to achieving appropriate asepsis and draping without the use of a drape becoming cumbersome (Thorne and Jackson, 2000).

Antibiotic use and selection

It is widely accepted that systemic antibiotics can be justified following Caesarean section in the ewe to reduce the chances of surgical site infections or deeper infections causing peritonitis following the adage ‘as little as needed and as much as necessary’, especially for surgeries performed on farm which at best can be classified only as ‘clean-contaminated’ (Scott, 2015; Phythian et al, 2019).

However, the literature provides minimal and varying advice on length, and selection, of antibiotics. Unsurprisingly, 98.1% of respondents administered systemic antibiotics, starting on the day of the surgery, and the respondents who did not had performed ‘salvage Caesareans’ where antibiotics were not required as the ewe was euthanased afterwards.

Consideration must be given to the class of antibiotic selected and broad-spectrum antibiotics with activity against aerobic and anaerobic organisms are indicated (Scott, 2015). Respondents tended to give either a 3- to 5-day course of antibiotics (and it is likely some variance here is a result of the use of long-acting products with 48 hours duration' per injection).

The lack of any significant variation in outcomes between use of category C or category D antibiotics suggests that further consideration and informed selection of antibiotics is required to ensure compliance with the recommendations laid out by RUMA (EMA, 2022).

Penicillin plus dihydrostreptomycin is a category C ‘caution’ antibiotic, and amoxicillin is a category D ‘prudence’ antibiotic (EMA 2022), which should influence selection for Caesarean section to reduce the antibiotic use within the group. Currently, 81.3% of veterinary surgeons are using category C antibiotics as their antibiotic of choice for Caesarean section within the ewe (Table 2). It is also worth noting that the datasheet maximum duration for Pen+Strep is 3 consecutive days only (NOAH, 2022a), compared with 5 consecutive days for Betamox150 (NOAH, 2022b).

Analgesia and anaesthesia

It should be commended that 100% of ewes undergoing Caesarean section received NSAIDs and it was noted that many practitioners are using the 1 mg/kg dose that is the licensed sheep dose for meloxicam in the Southern Hemisphere (Boehringer-Ingelheim (NZ) 2016; Boehringer-Ingelheim (Australia) 2016) and this should be the standard dosing instruction given when prescribed ‘off-licence’ within the UK rather than the 1 mg/2 kg cattle dose. The authors would also encourage all practitioners to ensure familiarity with the requirements for recording and prescribing meloxicam off licence and the statutory 28-day withdrawal period (meat), and that appropriate conversation is had with clients because of the lack of NSAIDs currently licensed in the UK.

Use of a sacrococcygeal epidural is commonly taught as part of the standard procedure for bovine Caesarean section by clinicians at a number of the UK veterinary schools, and it is the authors' belief that the use of a sacrococcygeal epidural is commonplace in practice for the bovine Caesarean section. In contrast only 10.3% of respondents utilised the sacrococcygeal epidural in their ovine Caesarean section. In their summary of the evidence, Phythian et al (2019) provided a balanced argument for the use of sacrococcygeal epidural contrasting the benefits (including reduction of abdominal straining and increased pain relief and ewe comfort) with the risks (short-term ataxia and potential impact on short-term suckling). Anecdotally, and in discussion with several colleagues within the group, it was felt that this was in some part a result of reduced surgeon familiarity with the procedure and the appropriate dosage.

As seen in the results, variation in the volume and composition of epidurals was observed. In their article on practical anaesthesia and analgesia in sheep, goat and calves Hodgkinson and Dawson (2007) advocated for 1.75 ml procaine hydrochloride and 0.25 ml xylazine epidural for a 70 kg ewe, while Hallowell and Potter (2008) advocated for 1 ml per 50 kg procaine hydrochloride maximum.

Similarly, notable variation was observed with volumes of local anaesthetic used to provide loco-regional anaesthesia. Research suggests a toxic dose of procaine hydrochloride of 6–10 mg/kg (Galatos, 2011; Phythian et al, 2019), which for a 75 kg ewe translates to an upper limit of 18.75 ml of a 40 mg/ml product (e.g. Pronestesic, FATRO; Procamidor Duo, Richter Pharma) or 15 ml of a 50 mg/ml product (e.g. Adrenacaine, Norbook Laboratories). While respondents appear not to have seen any significant adverse effects as a result of higher doses, it is worthwhile considering what volumes of local anaesthetic are being used in practice, especially as many within the group are using lower volumes without desensitisation.

Interestingly, only one respondent described diluting their volume of local anaesthetic with sterile water to provide a larger volume as described by Mueller (2017), so it is unclear if any other respondents utilise this approach to increase their injection volume causing an artificially high number of volumes recorded as above the toxic dose.

Outcomes

The results of this audit were presented at the Autumn IVC Evidensia (UK & Ireland) Farm Conference in Edinburgh, alongside a number of resources produced by the authors and the SCWG — these included a list of recommendations around antibiotic selection, infection control and surgical asepsis and the use of local anaesthetic in sheep. Safe operating procedure (SOP) documents were produced for ovine sacrococcygeal epidurals and Caesarean sections, approved by the IVC Evidensia (UK & Ireland) farm animal clinical board, and circulated among all practices within the IVC Evidensia (UK & Ireland) farm group.

Further research

The authors intend to repeat the audit in 2023, with a number of changes to allow further data to be captured and to assess the impact of this audit study on practitioners' selections within the group. The authors believe it would also be interesting to assess which types of clients are presenting ewes to veterinary practitioners for obstetrical difficulty, to allow a broader understanding of which clients are being engaged the most, and to allow follow-up questions around the barriers and motivators of larger clients to seek, or not seek, veterinary intervention for obstetrical difficulties. An additional question could be added into the audit questionnaire relating to flock size and purpose (e.g. smallholder, pedigree, commercial meat or dairy).

Conclusions

While confirming some commonly held beliefs (such as common causes of caesarean section and the uptake of NSAIDs), the current study also highlighted a number of quality improvement opportunities within the group. These included responsible antibiotic use and improving infection control measures. All of which were reflected in the farm animal clinical board approved best practice guides and resources produced. Repeating the audit for the 2022–2023 lambing season will allow the authors to understand the uptake of the recommendations and also increase the evidence based outcomes measures.

KEY POINTS

- A high proportion of veterinary surgeons are opting for European Medicines Agency (EMA) category C antibiotics as first line when EMA category D products (such as amoxicillin or penicillin) are proven to work well and are a more responsible use of antimicrobials.

- Practitioners are urged to consider reducing their use of EMA category C antibiotics in ovine obstetrical procedures, or to using it as a SMART goal under the Farm Vet Champions Scheme.

- The volumes of local anaesthetic used in ovine Caesarean sections is highly variable between individuals and consideration of the toxic doses should be given.

- There is widespread uptake of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug use during obstetric procedures in sheep, however, clinicians may not all be aware of the differing dose 1 ml/kg in sheep compared with the datasheet dose for use in in cattle.

- Feto-maternal disproportion remains the most common cause of ovine Caesarean section.