The importance of colostrum intake (Sawyer et al, 1977; O'Brien and Sherman, 1993) and the maternal bond (Nowak, 1996) in the first hours of life in small ruminants is known to be highly influential for survival. To date there are few studies observing doe and kid activity following parturition. Lickliter (1985) observed 60 Saanen does and their offspring in the periparturient period and Ramirez et al (1998) observed 65 Murciano Granadina kids in the first hour after birth, under more extensive, uninterrupted conditions in the USA and Spain.

Understanding doe and kid activities could guide developments in husbandry practices, utilising the doe's instincts to both improve goat welfare by allowing expression of bonding behaviours (Webster, 2011) and reducing kid mortality by maximising colostrum intakes (O'Brien and Sherman, 1993).

Currently no data are available for post-parturient activities of does and kids on UK dairy goat farms. This study observes does and kids following parturition, on a farm where it is routine practice to confine does with their kids in an individual pen shortly after kidding. It develops methodology for documenting behaviour in the form of an ethogram and offers some preliminary findings on patterns of activity. This paves the way for further study, the findings of which could help farmers to target use of resources on farm while promoting high welfare for dairy goats.

Materials and Methods

Goats observed were from a 2000-goat dairy farm and primarily of Saanen breed. Kidding takes place four times per year, and approximately 400 does give birth during each kidding block. The herd breeds both in and out of season, and all replacement does are bred on farm.

Does due to give birth were kept in a kidding barn separate to the milking herd. Shortly after giving birth each doe and her kids were moved to a 3 m x 3 m pen, bedded with straw and with water and total mixed ration available for a period of approximately 24 hours. These pens were located at the edge of the kidding barn, with the doe in sight of the rest of the herd but separate from the other does and their kids.

Colostrum sufficient to feed each of her kids was hand milked from the doe shortly after she gave birth. All kids were fed 300 ml of this colostrum via stomach tube as soon as they were born, even though they remained with and could suckle their dams. This is unusual for UK goat farms, where kids are generally left to either suckle their dams or are removed from dams at birth before routinely being fed colostrum (Anzuino et al, 2019).

The navels of kids were then dipped in 10% iodine solution. Does remained with offspring until mid-morning the next day, when does were removed to the milking herd and kids were moved to kid rearing accommodation or culled.

Developing the ethogram

An initial pilot test of a provisional protocol established which activities were practical to record. This involved two 1-hour observation periods. A provisional recording table was devised with columns for ‘suckling’, ‘sleeping’ and ‘miscellaneous’, with does and kids included in the same table.

Following this pilot test the activities listed in Table 1 were chosen for inclusion in the study.

Table 1. Activity definitions

| Activity | Definition | Code letter | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Doe | Grooming | Licking one of offspring | G |

| Lying down | All four legs tucked under body, including kneeling on forelegs or sitting on hindlegs | D | |

| Feeding +ration/placenta/straw | Ingesting and chewing one of straw, placenta or ration | F + S/P/T | |

| Neutral | Standing on all four legs, no apparent activities displayed or interest directed to any particular subject (e.g. not eating or drinking) | N | |

| Vocalising | Any position while bleating, not concurrently grooming or eating | V | |

| Drinking water | Drinking water from bucket in pen | Dr | |

| Kid | Searching for teat | Kid actively doing 2 out of 3 of the following: wagging tail, moving forwards while reaching out neck, feeling with muzzle, pushing with muzzle; directed to doe or other siblings | S |

| Suckling | Kid's mouth latched onto teat | F | |

| Neutral | As for does | N | |

| Lying down | As for does | D | |

| Sleep | Lying down with eyes closed | A | |

| Vocalising | As for does | V | |

| Play | Standing and showing both tossing of head and leaping forwards or sideways | P |

Trialing the ethogram

Five does and their 10 respective kids were observed for a total of 248 minutes each over the course of 5 days (one doe and their kids would be observed per day). Convenience sampling was used to obtain families to record, observing whichever doe gave birth when the observer arrived on farm. Observations were made by a single researcher seated 2–3 m distance from the pen. Scan sampling was used, recording a single behaviour for the doe and each kid at 2-minute intervals. Each activity was assigned a code letter to aid ease of recording, outlined in Table 1. Observations were recorded using pen and paper and time was kept using a Samsung J5 mobile phone. All observations started mid-morning, as soon as possible after the does gave birth. Additional information about does and kids was also recorded (breed, age, number of kids, body condition score (BCS), dystocia, colostrum Brix refractometer values, udder conformation).

The time taken for kids to perform activities after being fed colostrum by stomach tube were recorded, and also the time period between the kid first showing searching activity and first suckling.

Data were downloaded into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet and summary statistics were calculated.

Results

The headings in Table 2 indicate further parameters thought important to record for each doe. Values are given where available. With more practice using the ethogram, it would become much easier to routinely record all this information for each doe. However, because of the early stage development of the project some values are missing.

Table 2. Overview of does and kids observed

| Doe | Breed | Number sets of kids | Body condition score | Dystocia/required assistance | Udder conformation | Brix refractor value colostrum | Kids |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | British Saanen | First kidder | 3.0 | No | 11% | Kid 1 – FKid 2 – F | |

| 2 | British Saanen | Second kidder | 2.5 | Some difficulty kidding — kids meconium stained | 26% | Kid 1 – MKid 2 – F | |

| 3 | British Saanen | Unknown | ? | All 3 kids pulled out but no difficulty | Uneven and very large udder, one side low hung, conical teats | 21% | Kid 1 – FKid 2 – FKid 3 – F |

| 4 | Toggenburg | Unknown | 2.5/3 | No | Teats at hock level, small distinct teats, not overly large, even | Kid 1 – MKid 2 – ? | |

| 5 | British Saanen | Unknown | 3 | No | Udder good conformation, cylindrical teat, even halves, not hung past stifle | Kid 1 – M |

Kid activities

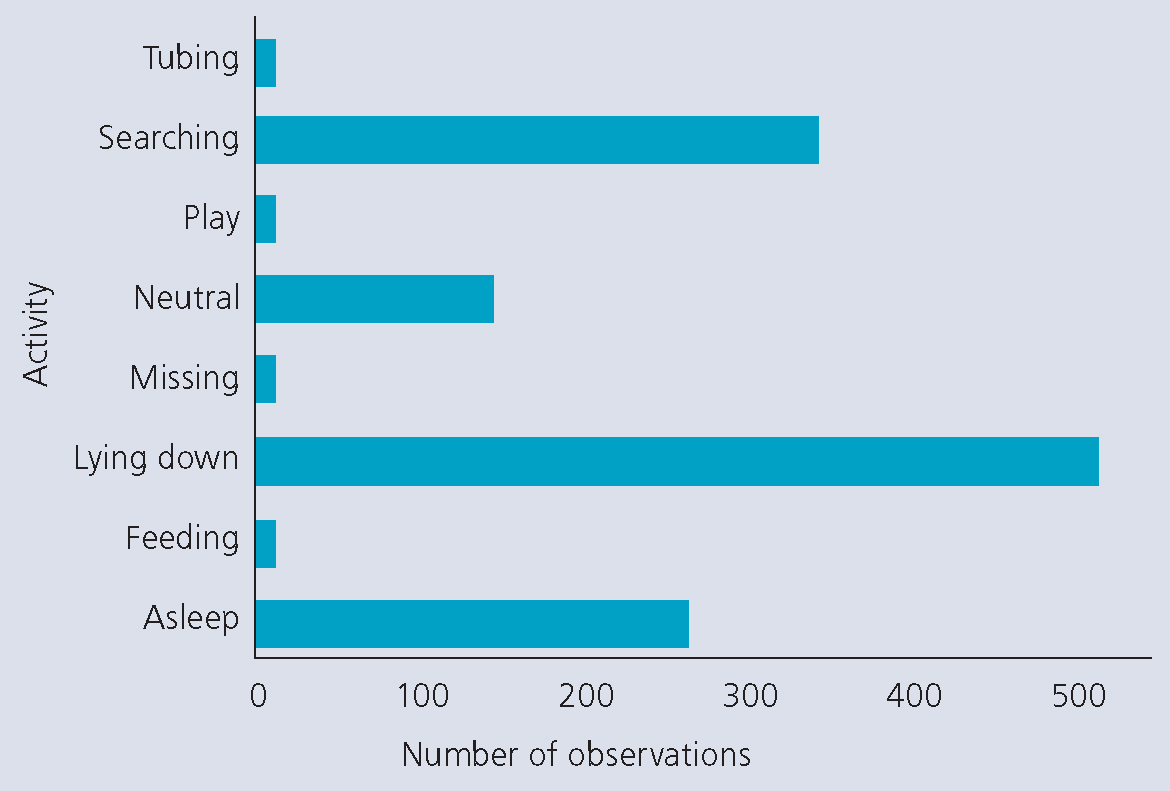

Each kid was observed for 248 minutes, meaning that 124 scan observations were done for each kid. This gives a total of 1240 observations over all 10 kids. Figure 1 gives a breakdown of these 1240 observations. It can be seen that ‘lying down’, ‘searching’ and ‘asleep’ were the most common observations. Relatively few observations were spent with kids ‘feeding’ or involved in ‘play’. There are a small number of observations where data are ‘missing’. These occurred in the early part of the trial, where the researcher was becoming familiar with using the ethogram. ‘Tubing’ represents time spent stomach tubing the siblings born to kids that were already being studied.

Differences between kids

Where kids performed a particular behaviour, then the amount of time spent performing the behaviour varied between kids. The extent of this variation is set out in the Table 3.

Table 3. Overview of kid population activity distribution

| Kid activity | Number of kids who showed this activity | Time spent performing this activity during the full observation period (minites) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | Inter-quartile range | Minimum | Maximum | ||

| Neutral | 8 kids | 29 | 21–49 | 4 | 74 |

| Lying down | 10 | 92 | 78–110 | 50 | 158 |

| Suckling | 7 | 6 | 2–12 | 2 | 14 |

| Searching | 9 | 68 | 60–92 | 24 | 104 |

| Asleep | 10 | 41 | 24–64 | 12 | 138 |

| Play | 3 | 4 | 2–16 | 2 | 16 |

Not all kids were seen performing all the behaviours listed. All 10 kids spent time asleep or lying down. Seven out of the 10 kids suckled and nine kids searched. One kid did not search or suckle. Three kids played. Eight kids were observed in ‘neutral’.

Variation in kid activities over time

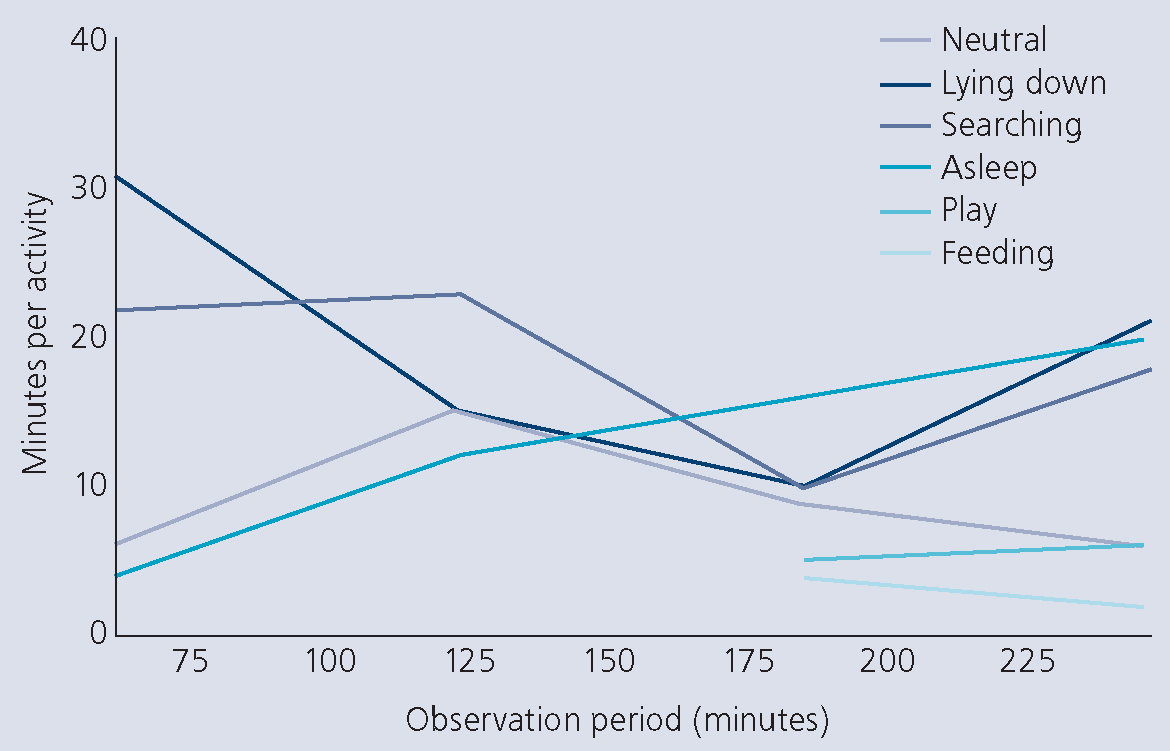

Figure 2 gives an indication of how behaviours of the 10 kids altered with time. The median time spent in a behaviour for all 10 kids was calculated for the first hour (0–60 minutes), second hour (61–120 minutes), third hour (121–180 minutes) and fourth hour (181–240 minutes) of the observation period. These four values were plotted and joined with a line so that patterns are easier to see:

- During the first quarter of all observation periods (i.e. 0–60 minutes), all kids were observed lying down at least once, eight kids searched for a teat, six kids stood neutrally, five kids slept and one kid suckled.

- During the second quarter of all observation periods (i.e. 61–120 minutes), eight kids continued to search, with little time spent lying down or standing neutrally. All 10 kids lay down at least once during this period, six kids spent marginally increased time asleep. No kids suckled.

- During the third quarter of all observation periods (i.e. 121–180 minutes), kids spent a greater proportion of their time lying down or asleep, compared with the first and second quarters. All 10 kids lay down at least once during this period and nine kids slept. Kids spent less time searching for a teat during the third quarter of the observation period than during the other quarters, although eight kids still attempted to search and three kids suckled. Two kids played for the first time during the third quarter.

- During the last quarter of the observation period (i.e. 181–240 minutes), nine kids increased the proportion of time they spent searching, 10 kids lay down, eight kids slept, two kids played and six kids suckled.

Table 4 indicates when kids were first seen performing each activity. Note that one kid did not do any searching and three kids did not suckle.

Table 4. Time periods between recorded kid activity and stomach tubing with colostrum

| Kid activity | Number of kids | Time period after being stomach tubed with colostrum that kid first performs the activity (minutes) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | Minimum | Maximum | ||

| Searching | 9 kids | 22 | 14–43 | 8 | 160 |

| Suckling | 7 | 168 | 110–206 | 38 | 222 |

| Sleeping | 10 | 52 | 22–108 | 10 | 140 |

| Time between first ‘searching’ and first ‘suckling’ | 7 | 132 | 46–214 | 16 | 222 |

Doe activities

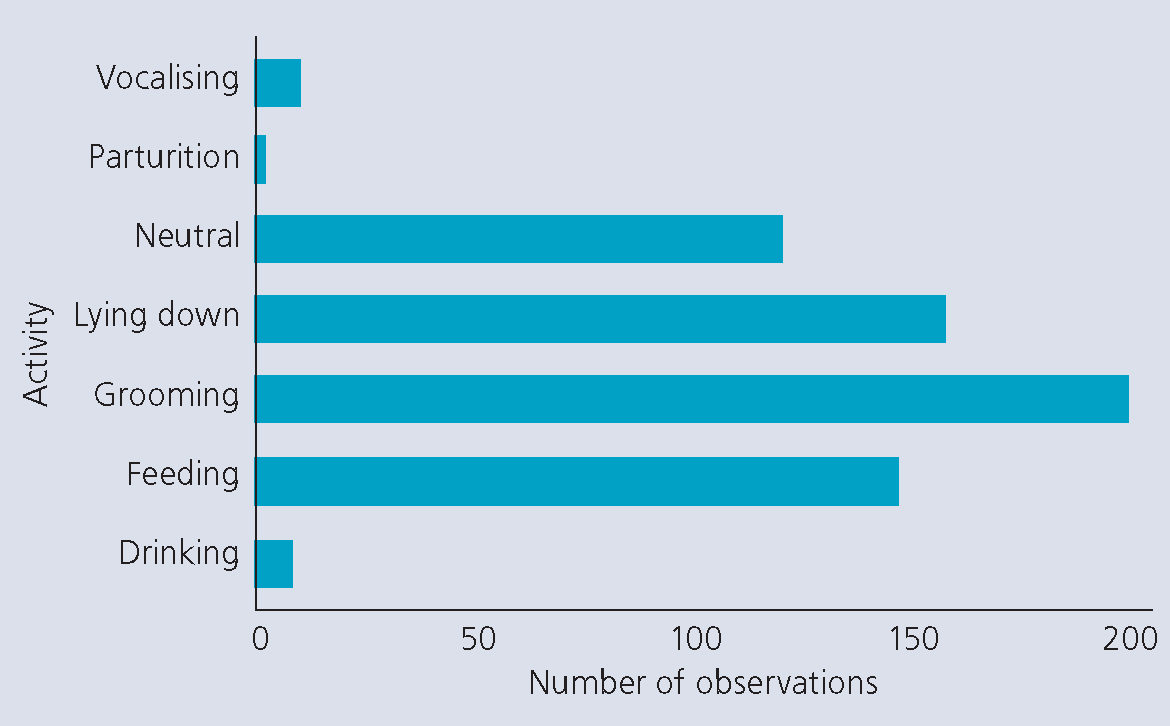

Each doe was observed for 248 minutes, meaning that 124 scan observations were made for each doe. This gives a total of 620 observations for all five does. Figure 3 gives a breakdown of these 620 observations. It can be seen that ‘lying down’, ‘grooming’, ‘feeding’ and ‘neutral’ were the most common observations.

Differences between does

Not all does were seen performing all the behaviours listed. One doe did not lie down, and one doe did not feed on total mixed ration/straw. Where does performed a particular behaviour, then the amount of time spent performing the behaviour varied between does. The extent of this variation is set out in Table 5, showing how much of the 248 minute observation period was spent in each activity. Across all does the most prevalent activity was grooming. The least prevalent activity was feeding on ration and straw.

Table 5. Overview of doe population activity distribution

| Doe activity | Number of does | Total time doe performed activity (minutes) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | Minimum | Maximum | ||

| Neutral | 5 does | 46 minutes | 40–58 | 22 | 76 |

| Lying down | 4 | 51 | 23–70 | 6 | 78 |

| Grooming | 5 | 80 | 52–104 | 48 | 112 |

| Feeding on TMR/straw | 4 | 31 | 15–43 | 6 | 48 |

| Feeding on placenta | 5 | 36 | 22–42 | 6 | 66 |

Variation in doe activities over time

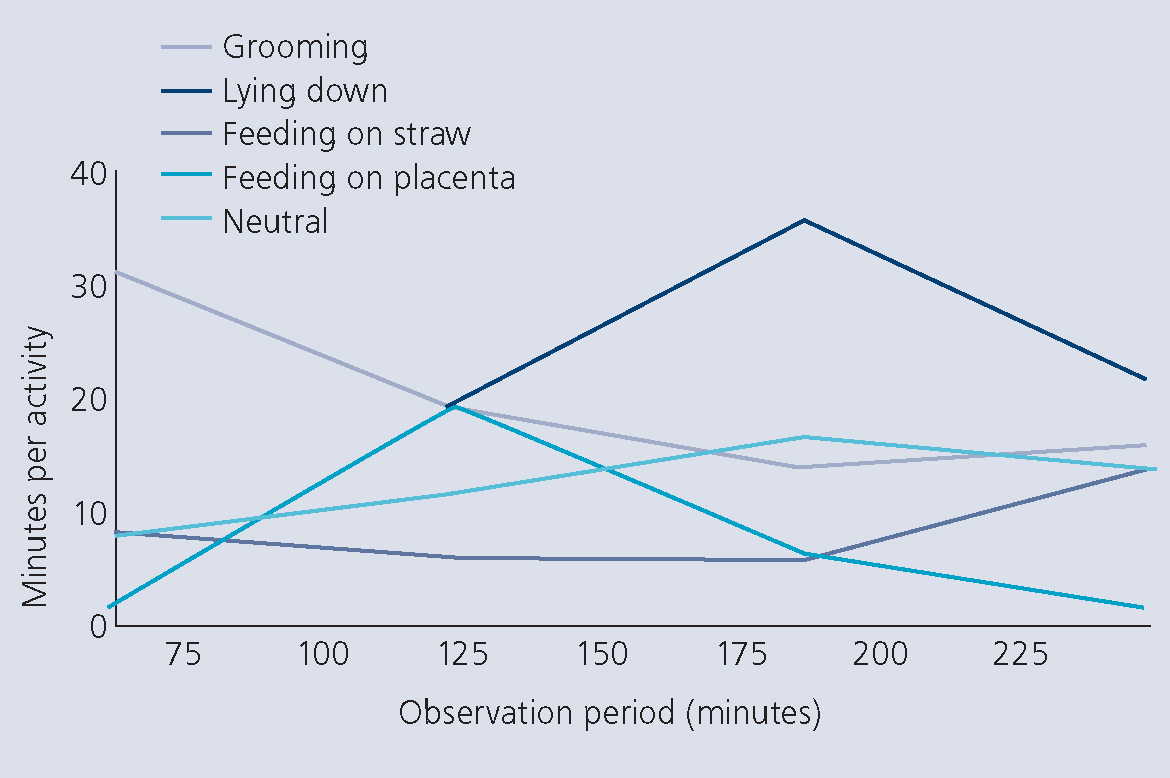

Figure 4 gives an indication of how behaviours of the five does altered with time. The median time spent in a behaviour for all five does was calculated for the first hour, second hour, third hour and fourth hour of the observation period. These values were plotted and then joined with a line so that patterns are easier to see:

- During the first quarter of all observation periods the dominant activity of does was grooming. Very little time was spent lying down, eating or standing neutrally, with the exception of Doe 2 who spent 22 minutes eating straw.

- During the second quarter all five does passed and ate their placenta. All five does groomed and three does first lay down. All does spent time as ‘neutral’.

- In the third quarter, three does spent an increased amount of time lying down and four does spent an increased amount of time neutral standing. Grooming activity decreased in all does. Three does continued to feed on placenta, four does spent more time feeding on ration and straw bedding.

- By the final quarter grooming marginally increased again in all does. However, the dominant activity was lying down, with four does choosing to do this. Feeding activity continued to increase in three does.

- ‘Vocalising’ activity was recorded for both does and kids. However, it was difficult to record concurrently with other activities, tending to happen in conjunction with these and thus was excluded from the analysis.

Discussion

Comment on the ethogram

The ethogram developed by this study was practical to use on farm and, after some initial practice, does and kids could be easily scored. Developing ethograms is an iterative process — they evolve with use and reflection. To date, some activities might have been misidentified. For example, ‘searching’ presented in numerous ways and could be mistaken for ‘neutral’ activity, as some kids stood still without wagging their tails but appeared to reach forward and sniff.

‘Play’ was the most difficult activity to define. It was eventually defined as head tossing and jumping but could be mistaken for more vigorous searching. Activities that occurred during the 2 minutes scanning interval will have inevitably been missed. For example, does’ grooming bouts often last only seconds. It could be possible to record at 1 minute or 30 second intervals to increase the precision of results.

Comment on the population sample

Findings need to be seen in context. The sample included in this study is small, using only Saanens and Toggenburg breeds, obtained using convenience sampling. Choice of sampling was limited by time available to carry out observations. Therefore, the findings of this study are not truly randomised and cannot be assumed representative for dairy goats across this farm or other UK farms.

Some thoughts on the behavioural observations made

Nearly all kids began to search for the teat within 1 hour after being fed colostrum by tube. This could suggest that attempts to search were driven by instinct rather than hunger. Doe ‘grooming’ and kid ‘searching’ activities followed similar trends. Does and kids spent the most time performing these activities in the first half of the observation period and they decreased concurrently during the second half of the observation period. It is possible that grooming by the doe stimulated the kid to undertake searching activity, even where the kid was not yet hungry.

In addition, the time-period between searching for a teat and suckling seemed prolonged, despite persistent searching activity of kids during the observation period. Again, this may in part be a because the kid was not yet hungry enough to suckle or it may in part be because of udder conformation making latching onto a teat difficult.

It was noted that kids tended to search dorsally on the udder but the does’ teats were often positioned close to the floor because of a pendulous udder conformation. Udder conformation was only noted for three does. However, udder scoring using validated scoring systems could be useful in investigating relationships between searching times and udder conformation.

One interesting observation was made when observing Doe 2 and the amount of attention that was given to each kid (Kid 3 and Kid 4). In this instance Kid 3 was groomed less overall than its twin for the duration of the observation period. Kid 3 did not search or suckle for the entire observation period, whereas Kid 4 did. The following morning Kid 4 was alert, mobile and clean, whereas Kid 3 was still meconium stained and unsteady on its hindlegs, suggesting that little grooming or suckling had taken place overnight.

Overall, findings suggest that strong bonding instincts remained between the doe and kid despite the human intervention of handling them and stomach tubing the kids.

Thoughts on developing the study further

This ethogram and the way behaviours are recorded can be further developed. Observations were made in person but in future could be made using several cameras recording video footage near the pen. This would allow more than one pen of does and kids to be recorded. Video analysis is time consuming but it should be practical and allow a larger, representative sample of does and kids to be studied and for a longer time period. Best positioning of cameras would need to be investigated. For example, sometimes it was difficult to identify behaviours being displayed if kids were hidden behind does or does were facing away from the observer.

Also, in any study it is important to investigate the ‘repeatability’ of measures, i.e. is the researcher consistent in how they score behaviours? Where more than one researcher is involved, do they consistently score behaviours in the same way? Video footage allows footage to be rewatched and reassessed.

Certain specific research questions come to mind. For example, in future a study, comparing kids tubed with those not tubed could illuminate the impact of early colostrum provision on activity levels. Where kids are not stomach tubed, the time it takes for them to latch onto teats and the ease with which they latch onto teats from udders with different conformation scores could be studied, as could the impact of the does’ nurturing behaviour on the kid activity. Differences between siblings could be analysed. Findings could help farmers better target how they use resources on farm. For example, a number of farmers already stomach tube kids if the doe has a particularly low-slung udder but findings might help them better identify other kids at risk of poor colostrum intake.

It may come into question the benefit of studying the maternal bond in dairy does and kids, particularly as UK dairy goat farms often remove kids at an early stage of life (Anzuino et al, 2019). However even if kids and does are being kept together even for a short period of time if we can maximise does’ natural instinct to feed and nurture kids, this surely has a positive impact on overall doe and kid health and welfare.

The UK public is taking an interest in the welfare of animals in dairy systems and expressed an interest in paying higher prices for ‘good dairy welfare’ for dairy cattle (Ellis et al, 2009). The UK dairy goat industry may be able to benefit from a higher price for milk by demonstrating a proactive approach to developing dairy systems that take into account the need to express these behaviours and demonstrates to the public an awareness of goats’ behavioural needs and how they are being met in a dairy system. If dairy goat behaviour is better understood and defined it is easier for industry professionals such as farm veterinary surgeons to make meaningful recommendations to farmers to help goats express these behaviours in the context of a ‘higher welfare system’, or it could be easier for milk buyers such as supermarkets or quality assurance schemes to stipulate measures to aid these behaviours to be expressed.

Better understanding of maternal behaviour, and other factors that may influence neonate colostrum intake such as udder conformation, may help farmers identify these traits. A scoring system could be developed from further data collected about doe maternal behaviour or conformation. The ability to score does on maternal ability, udder conformation etc. could be of benefit when selectively breeding does. For example, does that promptly interact with kids after birth, cleaning and drying them off and encouraging them to stand and search for colostrum, can be more easily identified and selected for breeding replacements. Another example would be understanding how soon we should expect kids to be standing and searching for the teat after birth, which may help identify weaker kids and signal to farmers and veterinary surgeons potential herd health issues.

Another application of this format of collecting data about goat behaviour could be to monitor what kids do when moved to youngstock accommodation away from the doe — how do they interact with their environment, how could we enrich their environment better, how does this affect their feeding patterns? Frequency of expression of normal behaviours may help signpost to other group health problems. Exploring these questions may help develop youngstock rearing systems that benefit kid health via encouraging expression of normal behaviours.

Even without specific research questions, it is still useful to carry out behavioural studies. Slowing down and taking the time to watch carefully and document findings often leads to new, unexpected information that is helpful for goat health, welfare and production.

Conclusions

In the post-parturient period on a UK dairy farm, the most prevalent activities observed in 10 kids were ‘lying down’ and ‘searching for a teat’. The most prevalent activities observed in five does were ‘grooming’ and ‘standing neutrally’. The ethogram developed proved practical to use, and lessons learned from this trial and findings could be used to develop further behavioural studies.

KEY POINTS

- This study develops and trials an ethogram by recording activities of 10 kids and their five does in the first hours following parturition on a UK dairy goat farm.

- Observations began shortly after does were confined in pens with their kids and the kids had been fed colostrum via stomach tube.

- The most prevalent activities observed in kids were ‘lying down’ and ‘searching for a teat’, and the most prevalent activities observed in does were ‘grooming’ and ‘standing neutrally’.

- The limitations of the study prevent definitive conclusions being drawn about periparturient doe and kid behaviour at this stage, however it develops a practical ethogram and reveals new information that could be explored further in future caprine behavioural studies.