It has without doubt been a convoluted journey which has brought us to where we are today with the Animal Health and Welfare Pathway (Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), 2023). Equally certain is that there will be much work to do now to roll them out across the farming sectors.

The vision for the pathway has evolved since the UK decision to leave the European Union made it inevitable that the model of state support for farming would need to change. Quite quickly, Michael Gove, the then Defra Secretary of State, coined the phrase ‘public money for public good’, indicating a move away from the existing land-based payments for farmers.

How to achieve this move while supporting the farming industry, enhancing traceability, animal health and welfare, as well as protecting the environment and maximising the trade potential of the food we produce was the challenge given to the group of people who have worked on developing the Animal Health and Welfare Pathway over the past 5 years.

Around 135 industry experts and 45 civil servants have contributed to the design and launch of the initial pathway which complements the Environmental Land Management Scheme (Defra and and Rural Payments Agency, 2021) and features a number of components.

The first, and the lynchpin around which the others hang, is the annual, funded veterinary visit (officially called the Annual Health and Welfare Review (Defra and and Rural Payments Agency, 2022)).

Vets have been at the heart of the design and delivery of the pathway and will remain core in the delivery. During the co-design phase, the veterinary subgroup has provided valuable input on a range of items.

1. Endemic disease and conditions control programmes

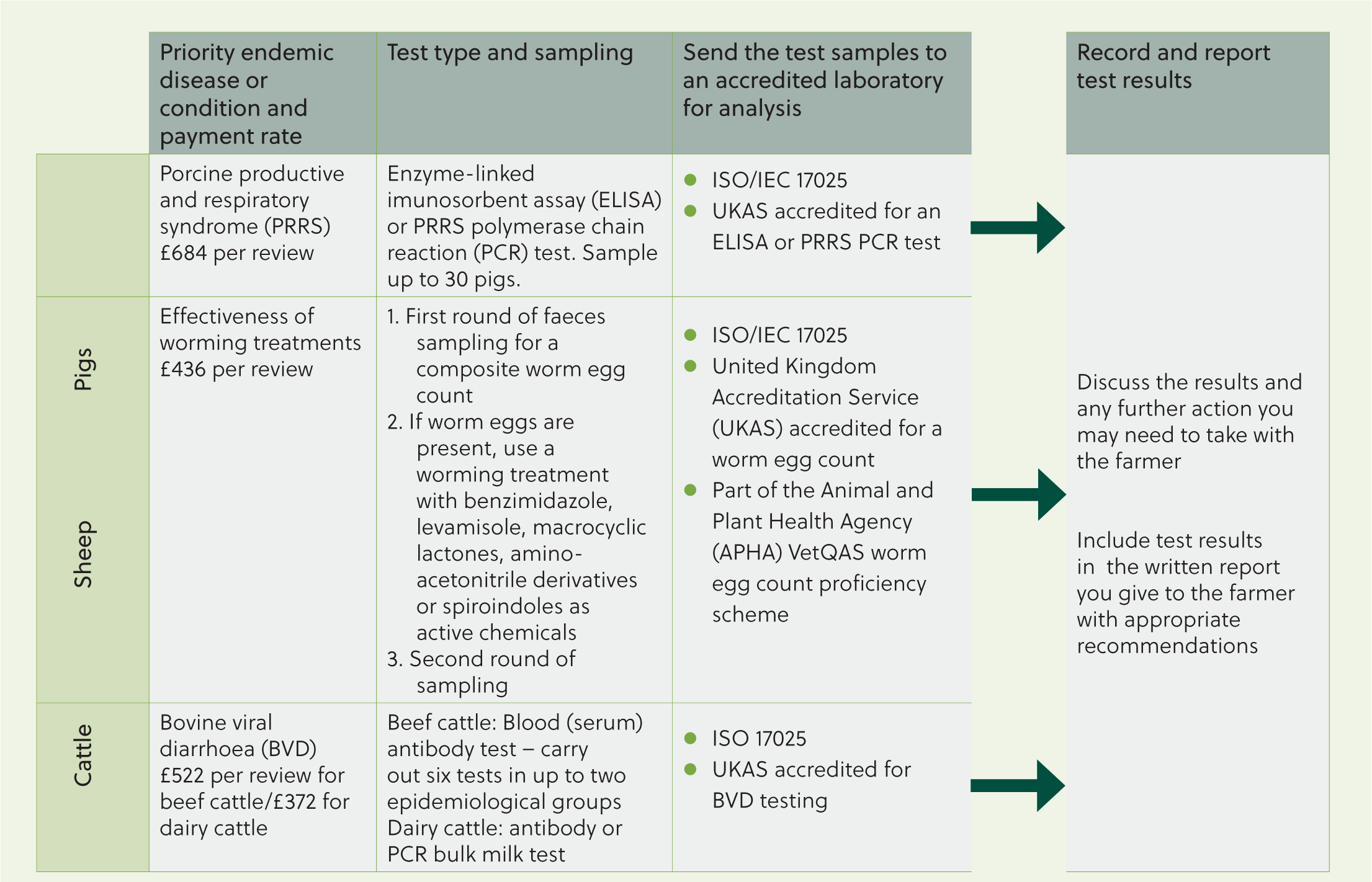

These are different for the different species involved. For cattle we have settled on bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD). For sheep there will be anthelmintic resistance testing and for pigs there will be porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) testing.

We have received some criticism for choosing conditions which are already under some level of local and national control, and I would like to tackle that here.

It is true that if we take BVD in cattle, BVDFree England has enjoyed some success in raising awareness of and supporting disease eradication on many farms. However, it is far from universal. The latest round of Stamp It Out BVD testing money was not fully utilised by the industry, and we still frequently find herds with persistently infected animals up and down the country. There are poor levels of compliance in some quarters, with the sale of high risk, and in some cases, known infected animals. This perpetuates and spreads the disease further. Additionally, neighbours' fences are sometimes just not up to scratch. This might be OK if you are in Lincolnshire and have many acres of arable farm surrounding you before the next cattle unit, but in areas of more concentrated livestock farming this can mean occurrences of ‘nose to nose’ contact which can spread disease locally. It is this final point which gives the pathway an edge where other initiatives have floundered. Because the pathway will be universally available, and ultimately universally required, we can help livestock keepers who have been doing the right thing to be better protected from neighbours who have perhaps not been so diligent.

A fundamental principle of the pathway is that they should be for everybody, and should move the level of understanding, standard of biosecurity and health and welfare aspirations forward a step on every farm, regardless of the starting point.

England is rapidly becoming the laggard with regards to BVD control against comparable agricultural industries around Europe. We must do something which will turn the dial.

2. Health and welfare grants

While we do not envisage an annual review being imperative for an application to the Animal Health and Welfare Grants programme, an application without veterinary support is likely to be considered somewhat inferior. Demonstrating that the equipment that a grant will fund will benefit the health and/or welfare of the animals on the farm will be a big tick in getting it approved. Some of the awarded grants will be quite significant and represent real investment in the future of farming.

3. Information to be gathered during the review

The information to be gathered during the review has been another source of considerable conversation and controversy during the co-design of the pathway, as competing considerations have had to be balanced. For example, respecting the confidentiality of conversations between farmers and their vets, while at the same time supplying enough data to HM Treasury to demonstrate value for public money (a public good for the public money if you will), has meant some quite tortured development of different aspects. Where we have ended up has been described by farmers who were part of the first pilot roll out as ‘something designed by people who obviously understand farming’. This will largely be evident in the delivery by those vets of the review visit on the farm. There is no multi-page tick box form that needs to be completed during the visit. Rather, there are some basic details: species; numbers; farming practices; disease testing results, which can be used anonymously to identify how well we are able to deliver on the goals of the pathway. The rest of the funded 2-hour session on farm can be used exactly as the farmer and vet decide. If farmers want to spend more time drilling into their farm's resilience in the face of a disease outbreak, then they can go for it. If they want to work together to build the case for a new livestock house, that's fine too. If they want to work out which mastitis control approach will be best for your farm, they might need more than the 2 hours (and they will need to fund that time with the vet), but they can put their time towards that goal, again, perhaps with a capital grant application flowing from it.

All this is seeking to develop the three pillars of a resilient, sustainable and high health and welfare farming industry in England (Figure 1).

The three pillars don't really have an order, but let's take Pillar 3 first: strengthening the regulatory baseline. As food producers, vets, government and citizens of the UK, there is a broad consensus that we want to see good standards of welfare on our farms. We also all know of examples where this has not been satisfactorily met. Any of us involved with farming can bring to mind images of farms where we think ‘if I was a sheep, I wouldn't live there’. As the UK exposes its goods for market on an international stage it is important to know that we can confidently assert our claims and back them with evidence. The pathway will be tools to help improve compliance and performance with the existing regulatory baseline, and over time, nudging that baseline to a position which finds the sweet spot of aspiration, financial sustainability and achievable standards on farm. This is not a pre-ordained end point. It will be developed through the ongoing process of co-design which has brought us this far already.

With that confidence, we can be more bullish with our marketing of English produce, with other nations developing their own methods of assuring markets. Existing assurance schemes will be better able to talk about lifetime assurance, and consumers will be able to buy with confidence, using the might of industry to educate and raise awareness of the farming facts behind the label.

This virtuous circle should support Pillar 1, in providing financial rewards for farmers. With public funding to support the transition to enhanced health and welfare farming practices, farmers can be protected from some of the costs of transition and deliver what we know all farmers want to do – consistently produce high quality, sustainable and high health product to the dinner tables of UK citizens.

So, enough of talking about what we have done together, and what it might achieve. How can farmers engage with the Animal Health and Welfare Pathway (Figure 2)?

Farmers should check that they are eligible. If they have at least one of the following then they are eligible:

- 11 or more beef or dairy cattle

- 21 or more sheep

- 51 or more pigs.

Next they should sign up digitally and agree to complete an Animal Health and Welfare Review within 6 months.

Together with their vet they will test for the priority endemic disease or condition on the farm (Figure 3). A discussion around health and welfare, medicines usage and biosecurity will be recorded by the vet.

Farmers will agree the most relevant actions with the vet and agree on a plan for the farm – this remains confidential between both parties.

The vet will then invoice for their time and the farmer will submit the summary of the review and receive the funding from Defra.

It is that simple. No checklists, no online forms, just an opportunity for the farmer and vet to discuss health and welfare issues specific to the farm and agree the most relevant actions.

The bigger picture

The first part of this article has focused on what is in the review, why we are doing it and how you might go about setting a review up. There are some overarching goals that will be beneficial spin offs if we get this right.

Firstly, antimicrobial stewardship. Nobody likes using antibiotics. They cost money, and often, it points to a failure of some system when they are needed. The mantra of ‘as little as possible, but as much as necessary’ is a helpful one when it comes to antimicrobial usage. The good news is that the agricultural sector has made huge strides in recent years. Overall, we have seen a halving of antibiotics prescribed on farms (Defra and Veterinary Medicines Directorate, 2021), with an even steeper fall off in the antibiotics in the protected categories, considered highly important in human health.

This overall gain hides some variance in performance across different sectors. Pigs arguably had the furthest to move, but have done so amazingly well. Red meat and dairy are slower to progress. Selective dry cow therapy has been a great success story (I am old enough that I was taught ‘every quarter, every lactation’ when it came to dry cow antibiotic treatments) and we have significantly reduced the number of dry cow treatments nationwide. Youngstock treatments remain stubborn. We need to continue to build on the gains we have made. The World Health Organization (2021) believes that antimicrobial resistance is one of the biggest threats to human health in the next generation. If we do not continue to reduce resistant strains of bacteria, then my generation (currently aged 45) may have to make a choice between not having a hip replacement, or risking death from a post-operative infection.

Endemic disease reduction on farm (often viral diseases) will be the next great step we take in reducing the need for antibiotics to treat the secondary pathogens.

As we move towards a net-zero carbon target by 2030 in the agricultural sector, we need to look really closely at losses. Arguably the greatest carbon cost on farm is the suckler who loses a calf, or indeed, the loss of that calf itself from the food chain.

The pathway will not be ‘the’ answer to these challenges, but by raising the bar for the lowest performing farms, and supporting the best performing, we tip the scales in our favour incrementally.

On a personal note, I believe passionately in the role of agriculture in the future of the UK. I see this through a food security lens, a countryside stewardship lens, an economic lens and a projecting lens which puts us firmly on the world stage as leaders, innovators and ultimately, skilled practitioners of the art of livestock keeping.

This country needs agriculture. The launch of Animal Health and Welfare Pathway is the first step in investing in agriculture to ensure its bright future. LS

KEY POINTS

- Vets have been at the heart of the design of the Pathway and will remain core in the delivery, particularly in relation to the Annual Health and Welfare Review.

- The information to be gathered during the review has been another source of considerable conversation and controversy during the co-design of the Pathway, as competing considerations have had to be balanced.

- Endemic diseases of conditions to be tested for include bovine viral diarrhoea for cattle, anthelmintic resistance testing for sheep and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome testing for pigs.

- Antimicrobial stewardship will be a beneficial spin-off if the industry gets this right.