In this article we invite veterinary surgeons to think beyond the traditional boundaries and consider how the skillset they have obtained through their degree course and work experiences can contribute to animal health outside perceived boundaries. We do this by sharing our personal experiences having worked in various environments (practice, academia, industry). We hope this may inspire some of the 23% of veterinary surgeons who would currently state ‘they would not do the degree again’ and the 39% who were ‘undecided’ (RCVS, 2019). This survey had a response rate of 10 279 (32%), counting only the fully completed questionnaires, with which we acknowledge a potential bias that may be present in the results (Table 1).

Table 1. Main area of work

| Type of organisation | % |

|---|---|

| Small animal (including exotics) practice | 52.6 |

| Mixed practice | 11.7 |

| Equine practice | 5.5 |

| Farm practice/production animal practice | 3.2 |

| Other first opinion practice | 0.4 |

| Referral practice/consultancy | 6.4 |

| Zoo/wildlife/conversion | 0.7 |

| Defra, APHA, FSA, FSS, DAERA | 2.8 |

| Meat hygiene/official controls | 1.8 |

| Other UK government | 0.5 |

| Overseas government | 0.7 |

| Veterinary school | 4.7 |

| Other university/educational establishment | 1.2 |

| Commerce and industry | 2.9 |

| Charities and trust | 1.9 |

| Portal | 0.1 |

| Telemedicine, tele-triage | 0.4 |

| Other | 2.9 |

The most frequently cited reasons for planning to leave the profession (for reasons other than retirement) are poor work–life balance, not feeling rewarded/valued (non-financial), long/unsocial hours and chronic stress (RCVS, 2019).

The biggest challenges to the profession in 2019 were client expectations/demands and stress levels; in addition, there are also high levels of concern about the changing structures in veterinary practice ownership.

We discuss these main areas of concern in the environments we have worked in, to hopefully help others find their best fit and start their discussions. With a clearly delineated path of school, veterinary school and veterinary practice, it can be difficult to know where to start with considering other options, and the veterinary degree can open many doors; the challenge is identifying and having the courage to open them!

Considering the most frequently cited reasons for planning to leave the profession for reasons:

- Poor work–life balance

- Not feeling rewarded/valued

- Long/unsocial hours

- Chronic stress

1. Poor work–life balance

WW: (Boxes 3 and 4) My main learning in practice, academia and industry is that you should not wait until someone takes care of you; you are highly trained and responsible for yourself so if you are not happy with something, you need to explore alternatives. First, discuss the mismatch with your current employer, as they may have other options you never thought about and as they presumed you were happy (no news is good news, right?).

Box 1.CV at a glance Wendela Wapenaar

- Practice

- Mixed practice (locum), the Netherlands

- Dairy practice, New Zealand

- Farm practice, UK

- Academia

- Residency (Ruminant health), University, Canada

- PhD, University, Canada

- Lecturer and Associate Professor, UK

- Industry

- Dairy Innovation Manager, Germany

- Global Farm Animal Project Lead, USA

Box 2.Career path Wendela WapenaarI started as a locum straight after I got my degree, as I already knew I was going to work abroad soon afterwards. I took my first permanent job in dairy practice in New Zealand as I like to travel and wanted a job in dairy practice. After 2 years in New Zealand, I moved to academia as my partner wanted to pursue a PhD in Canada, and undertook a residency, enabling me to combine practice and research. I never expected to enjoy research and always said ‘I would never go back to uni’ after I graduated. However, during my residency I enjoyed teaching and research. I then moved to the UK and worked for a brief period in farm practice. I did find the job quite different from veterinary practice in the Netherlands or New Zealand. The invitation to build a brand-new farm animal teaching track at a new veterinary school was an exciting opportunity to move back to academia. During 13 years in academia, I discovered that innovation is my interest, in addition to the dairy industry and when the opportunity for Dairy Innovation Manager came up in an animal health company in Germany, I knew it was time for a change. I now have a similar position in the US-based company which I thoroughly enjoy.

Box 3.CV at a glance Liz Cresswell

- Practice/academia

- Farm animal internship (80% practice, 20% research/teaching)

- Practice

- Veterinary practice — mixed (80% dairy), Australia

- Veterinary practice — farm animal locum, UK

- Academia

- PhD — withdrew after 11 months

- Associate Fellow of the Higher Education Academy

- Industry

- Regional veterinary adviser (ruminant)

- Other

- Nuffield Scholarship 2022

Box 4.Career path Liz CresswellHaving enjoyed my research project at university I wanted to continue at the interface of practice and academia by beginning my career with an internship. After successful completion of my postgraduate certificate, I wanted to consolidate my clinical skills and become more confident with the everyday workings of farm practice. I moved to mixed (predominantly dairy) practice in Australia where three busy spring calving seasons certainly allowed me to achieve my goal! I can highly recommend working abroad for the chance to experience different perspectives and methods. Having been interested in research a PhD seemed like the next logical step, so I was delighted to be offered one back in the UK. Alongside the PhD I valued the opportunity to locum to provide some extra income. However, I soon realised that academia was not quite what I was looking for and after a lot of discussion and deliberation made the difficult decision to withdraw from my PhD. This left me feeling like I was back at square one, needing to re-evaluate the direction of my career. Fortunately as veterinary surgeons we have plenty of skills to offer and it was not difficult to pick up locum work while I worked through the next steps. I invested in the VDS ‘Group Career Coaching’ course (https://www.vds-training.co.uk/courses/event/group-career-coaching), which was invaluable. Through this I signed up to Noble Futures recruitment consultants which is where I saw my current role advertised. I phoned on a whim as I thought it sounded interesting but had never considered a career in the pharmaceutical industry — 18 months later I am still loving my work as a Veterinary Adviser! I have also recently been awarded a Nuffield Scholarship which will enable me to combine my interests in farming and travelling alongside my job.

Work out what is important to you and why; use coaching or start with thinking about your needs/values (e.g. http://www.cherylweir.com/assessment/navintro.html) and check how your job (can) meet(s) those criteria.

In my experience your work–life balance is controlled by your-self and not so much the environment/type of job; your employer may stretch you as much as possible, and it is up to you to work out where your limits are and clearly communicate those. Some line managers may take on this role, but this is often not the case and it is up to your to define your ideal work–life balance.

LC: (Boxes 3 and 4) I enjoyed the pace of farm practice by day (Figure 1) and having time in the car between calls is one of the perks of farm practice not afforded by the intense pace of small animal practice. However, out of hours (OOH) work is more difficult to avoid in large animal practice and imposes on work–life balance. Finding practices where I was remunerated for a proportion of my OOH work and perhaps even more importantly, received time in lieu, helped considerably to take some control back for my work–life balance.

Locuming was another way in which I took back control of my own work–life balance. Although this comes with its own pressures of managing your own business, being able to dictate your own working week can be empowering and I found this enabled me to better deal with the stress of being on call and give myself recovery time where needed.

2. Not feeling rewarded/valued

WW: Industry is the preferred place for me to experience being valued/rewarded, as clear guidance is in place regarding expectations and there is a clear value put on their workforce. Having adequately trained and motivated people to take on people-related roles is key in keeping your workforce feeling valued and appropriately rewarded.

There is a distinct opportunity for professional growth (e.g. taking on more responsibility, promotion etc.) in academia (Figures 2 and 3) and industry (Figure 4 and 5); this is more challenging in farm practice. However, you can develop into a specialist (e.g. youngstock, mastitis, nutrition) or someone who develops other areas in the practice (e.g. mentorship, social media, marketing). Feeling valued can mean different things for different people (money, cake, days off, compliments…), so think about what it means to you and make sure your employer knows that too. And remember that no job is perfect…so pick your battle, work out what is really important to you and realise what you are willing to accept (e.g. bureaucracy, after hours, admin work, individualism).

Spontaneous support with career development is not something I have experienced in practice or academia but have had in industry. However, when I took initiative and asked (when in practice and academia), I have found employers willing to support me, so a pro-active approach is needed here.

Industry is more fast-paced and has a clear business model, like a veterinary practice. I found this more challenging in academia.

LC: As vets we sometimes have a tendency to work ourselves into the ground and to feel that you are not being valued for it can add insult to injury. This is where I think it is important to understand your own needs and values — what is most important to you? Financial reward? Time to work on certificates? Career progression? Networking opportunities? Subsidised gym pass? Establishing your ‘non-negotiables’ and discussing these with your employer can help to set clear boundaries and allow you to flourish in the areas that are important to you — this is true of whatever sector you work in. One of the biggest opportunities I have had is being awarded a Nuffield Scholarship, and my employer being flexible with regards to the time commitment this entails, as well as recognising the benefit for both myself and the company makes me feel valued as an individual; valuing employees results in rewards in both directions.

Your needs and values may dictate the progression you are looking for in your career and therefore the business model that suits you best — for example, independent practice may offer more opportunities to climb the ladder towards business ownership and with fewer restrictions imposed by a corporate framework. However, being part of a large corporate group may offer networking and clinical progression opportunities, which are harder to achieve in independent practices.

3. Long/unsocial hours

WW: In practice the working conditions were good in my experience, and after-hours work was the main drawback. I have found the majority of my practice bosses to be flexible with regards to time. The expectation of being ‘in the office’ to ‘wait for a call’ has happened on one occasion, which was demotivating from my point of view.

In farm practice I sometimes felt ‘controlled’ by my phone, in academia it will be teaching timetables, in industry it is targets and deadlines. How you respond to those can be different so finding out what suits you is important. I do not mind out of hours work from home, as long as I can control my own calendar for a large part, so evening calls with the US are not an issue to me. Everyone is different though, so there is no one size fits all and you need to figure out what is important to you. A coach has really helped me realise this; previously I wanted to be good at everything (teaching, research, practice) but did not feel I achieved this. A coach helped me realise what my key values and needs are, and this has helped me define what is important to me in a job.

As I like to travel and meet new people and places, a job in practice in the long term was not my best fit, as clients value a long-term relationship with their veterinary surgeon. I learned I am result driven, and therefore like goals and transparency. This is what I missed in academia; I think the key aim is to train students to be the best veterinary surgeons, however my career progression was based on different targets (research, academic admin tasks and leadership).

LC: As I mentioned above, there is an element of long/unsociable hours in many career paths, but particularly in farm practice where middle-of-the-night emergencies are unfortunately an inevitability. Working in industry, I can categorically say I do not miss the pager on my bedside table at night. On the other hand, I am often required to spend several nights a week away from home and can spend many more hours on the road than I ever did as a veterinary surgeon in practice. When I started my PhD, I thought I had hung up my waterproofs at least temporarily, but within a month the local practice phoned up asking if I was available to cover a few on-call shifts, which ended up as a longer-term locum position. It turned out I surprised myself with a renewed enthusiasm for OOH work when not doing clinical work all day too — a change is perhaps as good as a break after all.

It also was not long before I was back in the waterproofs in the clinical skills centre and on the university farm teaching students, which was another string to my bow and allowed me to gain a teaching qualification in the process. Although teaching is not currently my main area of interest it is a transferable skill that I could use in the future if I wanted to explore another area of the profession involving fewer unsociable hours.

4. Chronic stress

WW: In all my jobs I interact with people, which can cause stress; it does not matter much which job I do, although the type of people can be different (farmers, vs students vs colleagues). Challenging colleagues can cause stress; I do not see any difference regarding type of work environment; most of my colleagues are great. Industry is more collaborative compared with academia; in academia you are rewarded (with promotion and research grants) for progressing your own career, which can be in competition with your academic colleagues. In industry you get rewarded by achieving targets with your team.

Job security is better in academia, going through an integration of two large animal health companies has taught me that even though you are good at what you do, you may not have a job if there is someone else in the acquiring company doing that job already.

Client and line manager expectations can cause stress; doing a C-section on your own is not good for veterinary surgeon or patient, and support here is key. I think support is particularly important in practice, as the stakes are high (life/death). In academia and industry, I felt this less challenging, as often you can think about something, ask a colleague etc and there are often more colleagues to depend on.

Bureaucracy used to cause me lots of irritation and stress; although I learned to deal with this much better over time, it is still something I find much more stressful than dealing with tricky colleagues, deadlines or continuous change. I have learned to pick my ‘bureaucracy battles’ from my PhD supervisor. Both academia and industry have the characteristics of a large company, there is bureaucracy; in practice I found bureaucracy hardly existed.

In industry I am in a role where I can innovate, work as part of a team and have clear targets. Sometimes these targets shift for reasons that are difficult to understand; working for a stock market listed company has different drivers compared with academia where students and government are the main sponsors, or practice where your clients drive demand. I like the speed with which decisions are made, as (even though they are not always the choice I would like to hear) there is clarity, and most decisions are made objectively.

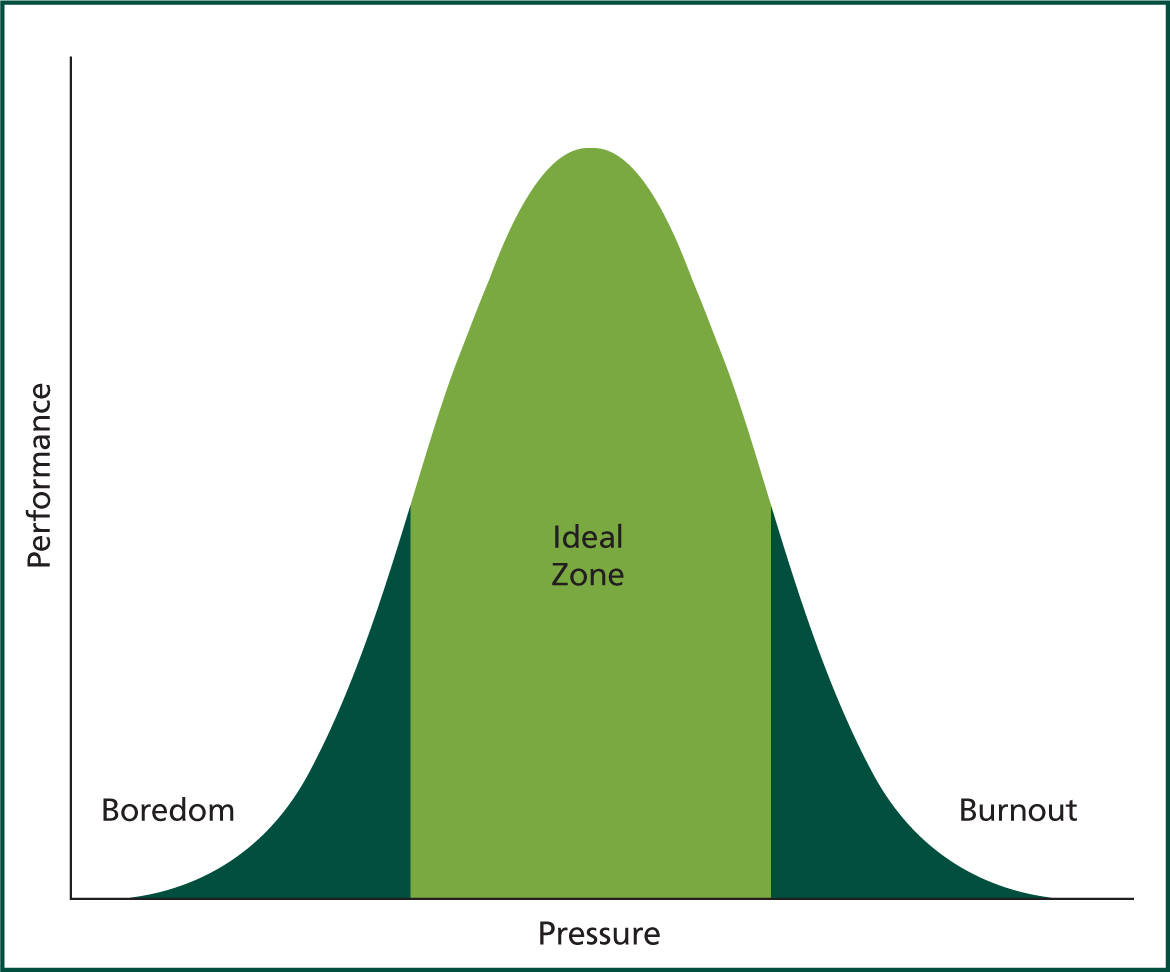

LC: Stress can come in all different forms and I cannot imagine any areas of veterinary medicine where it is not a factor. During group career coaching I discovered the ‘pressure-performance graph’ (Figure 6), which is applicable to most fields of work. The ‘pressure’ which can tip things over into the burnout zone might look different for different roles, but the principle is the same. Often these are external factors, and some days will naturally fall one way or the other, but too many over to the right-hand side of the graph can lead to chronic stress and burnout.

In practice I found that chronic stress came from tiredness and a lack of ‘recharge’ time. Locuming helped me to break this pattern and get a change of scenery, keeping it interesting by seeing how practice looked in different places. However, for some people the change of working in different places, for different clients and also running your own business, is a greater stressor, so locuming may not be the best fit.

During my PhD I experienced the other end of the scale where I was not sure of the direction of my research so stagnated with driving it forwards — this was a new type of stress for me, but is not necessarily reflective of everybody's experience in academia where it can feel like there are many plates to be spun at once.

Industry is an environment where I have experienced the full spectrum of the pressure-performance graph. I can manage my own workload to an extent, which helps to even out the days and keep me in the ideal zone. However, my work is often driven by the rest of the team and veterinary surgeons in practice, so there is always some unpredictability. For example, if customers become unable to attend meetings then my day might be quiet, but this means I can catch up on other tasks and be flexible with my working hours. At the other end of the scale, balancing being on the road all day with running multiple projects, as well as responding to customer calls can be stressful and mean working extra hours at times.

Conclusions

A career as a farm veterinary surgeon is versatile and provides many skills that can be used and transferred both within farm practice and beyond — we hope that by sharing our experiences we can help other veterinary surgeons find their best fit. A veterinary degree can open many doors; we invite you to think beyond the traditional career path, evaluate your skill set and contribute to animal health in the widest sense.

KEY POINTS

- Everyone is different, so find something that suits you and do not try to comply with expectations from others; what others enjoy is not what you need to enjoy!

- Do not be afraid to give something else a try; what have you got to lose? There is plenty of work available for veterinary surgeons so you have many options.

- Contact people who are in different jobs to hear their experiences, and for yourself, proactively pass on your experiences to better inform future colleagues. Online resources such as ‘Vets: Stay, Go or Diversity’ and the VDS' Group Career Coaching courses are two such examples.

- Take pride in what you have; a veterinary degree is versatile with regards to job opportunities worldwide, it truly is an opportunity.

- Try personality profiling to help you understand your working type. This will help you to understand what drives you and gives you tools to make a positive difference to your workplace and beyond. Dominance, influence, steadiness, compliance (DISC) profiling and Insights (https://www.insights.com/) are two commonly used examples.

- There are many and varied uses for a veterinary degree, both inside and outside of the profession.