The majority of UK livestock farming is certified through a farm assurance scheme. Herd and flock health planning form a core element of scheme standards, and farm vets are responsible for producing and certifying these plans. Farm assurance schemes' health planning requirements are therefore an excellent opportunity for farm vets and their clients to work in partnership to improve the health and welfare of the animals under their care. Despite this, the value of these interactions to both vet and farmer can be highly variable and, in a world where farmers and vets are time- and resource-poor, both parties can view the process as a costly tick-box exercise. The current UK-wide review of farm assurance schemes, along with new, post-Brexit sustainable farming payment schemes being implemented across the devolved nations, offers an opportunity to reflect on the current approach to health planning and reframe this aspect of assurance as a practical, impactful and rewarding process.

Farm assurance schemes

Assurance schemes are voluntary schemes that establish and regulate standards covering food safety, animal welfare and environmental protection. A farm-to-fork review of UK farm assurance schemes is currently underway by an independent commission (National Farmers Union (NFU), including NFU Cymru and NFU Scotland, the Ulster Farmers Union and the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board). The commission is evaluating up to 14 different schemes to assess their value to scheme members, the standards they set and how they fit into the wider regulatory landscape.

The main farm assurance schemes for ruminants in the UK include Red Tractor, which covers about 75% of UK agriculture and has separate schemes for various sectors. Other prominent schemes are Quality Meat Scotland (QMS) for cattle and sheep, Welsh Lamb and Beef Producers (WLBP), Northern Ireland beef and lamb scheme, RSPCA Assured focusing on higher welfare, and Soil Association for organic standards, which also inspects organic farms for Red Tractor.

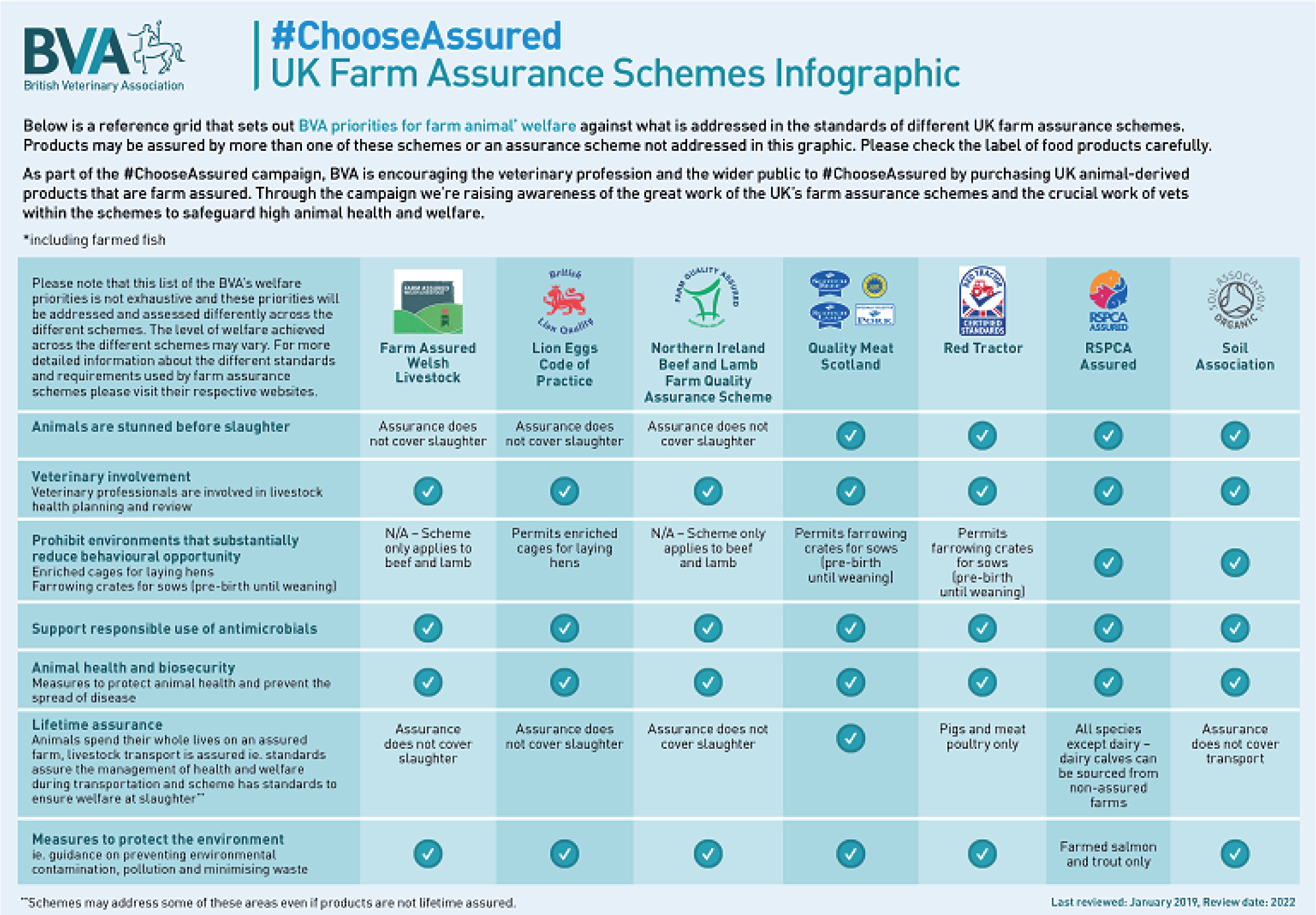

Due to the number of different schemes, which all have different scheme standards, it can be difficult for consumers to understand what membership of the scheme means and there has been evidence showing that scheme membership has limited influence on consumer buying behaviour (Deconinck and Hobeika, 2023). The British Veterinary Association's #ChooseAssured campaign includes a useful poster (Figure 1) outlining the key differences between some of these schemes, as measured by their guiding principles of farm assurance.

The vet's role

Farm vets have a critical role in the farm assurance process, from development to implementation and review. One core role of the vet in farm assurance schemes is to under-take and certify regular herd or flock health plans to allow farms to comply with scheme rules. More focused aspects of health planning are also being incorporated into new, post-Brexit government funding models for farming, including the Animal Health and Welfare Pathway in England, the Animal Health Improvement Cycle as part of Wales' Sustainable Farming Scheme, the Preparing for Sustainable Farming Scheme in Scotland, and Northern Ireland's Farm Sustainability Payment.

Vets need to feel motivated, capable and have sufficient opportunity to undertake health planning (Bellet et al, 2015). It is, therefore, imperative that vets are confident and able to conduct engaging, effective and ambitious animal health planning visits with their farmers, which translate into valuable improvements in animal health and welfare. Vets should be happy to charge appropriately for the time taken to produce detailed and impactful health plans, although this can be a barrier for both farmers and vets.

There has been extensive research in recent years exploring how farmer and vet interactions can impact animal health and welfare, leading to a good body of evidence that we can use when undertaking health planning. Much of this evidence emphasises the value of quality face-to-face interactions, with less focus on paperwork and more of a focus on practical changes. Both vets and farmers value meaningful discussion on animal health but can become disengaged when farm assurance is targetdriven and heavily dependent on record keeping (Escobar-Tello and Demeritt, 2016)

When it comes to animal welfare, a continuous improvement model for health planning, using the principles of quality improvement, is considered best practice (Main et al, 2014). It is known that vets tend to use a paternalistic, directive approach when giving herd health advice, however, the development of a partnership approach is more likely to succeed in bringing about the behaviour change needed to implement health advice (Bard et al, 2017). A farmer-centred approach, focussed on improved communication, a relationship based on trust and shared understanding has been shown to increase the likelihood of change (Bard et al, 2019).

Proactive and focussed animal health planning leads to improved antimicrobial stewardship (Speksnijder et al, 2017) and reduces overall treatment incidence across several diseases (Ivemeyer et al, 2012).

What makes an ‘active’ health plan?

To maximise value for both farmer and vet, animal health planning should be interactive and flexible, ensuring the herd or flock health plan remains a living, relevant document. To boost practical impact and engagement, this planning should occur face-to-face on the farm, with pre-paratory work beforehand and write-up aft erward. Meaningful engagement in health and welfare topics is crucial, alongside a continuous improvement model that reviews past progress and sets future goals. Data analysis, KPIs, and benchmarking aid problem-solving and accountability. The whole farm team should be involved, identifying the farmer's focus areas and tackling ‘low-hanging fruit’ for greatest gain. A medicine cupboard health check and medicines review complete the process. Good animal health planning takes time and should not be rushed. Health planning that takes place off the farm, over the telephone or even entirely in the absence of the farmer does not represent good quality interactions and should not be considered adequate as they are unlikely to lead to behaviour change or improvements in health and welfare. When providing high-quality advice, vets should charge appropriately and be able to demonstrate the value of these interactions. Maximising the opportunities available through new farming support schemes in the devolved nations can make health planning more worthwhile for farmers by incorporating specific disease management strategies. Done well, animal health plans can be highly productive, honest, and proactive consulting sessions that lead to measurable improvements in animal health and animal welfare, alongside strengthening the vet-farmer relationship and improving job satisfaction for farm vets.