Bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD) has been the focus of much attention over the past decades in the UK, as a disease that impacts the cattle industry, with Scotland starting the discussion and taking action to remove the disease from their national herd. The Welsh industry began discussions on following suit and this led to a voluntary programme – Gwaredu BVD.

The Gwaredu BVD Scheme

At the Royal Welsh Agricultural show held in July 2017, the Gwaredu BVD Scheme was launched. Industry led, this scheme was conceived as the first, and voluntary, part of a pathway for the Welsh cattle industry to achieve eradication of BVD in Wales. In total, £10 million was made available for BVD control activities through the European Rural Development fund and the Welsh Government. This project was managed collaboratively by the Royal Veterinary College and Coleg Sir Gar.

The scheme was supported by a wide range of stakeholders within the Welsh cattle industry and many of these supporters formed a steering group to help guide the project. Importantly, these stakeholders include the Farming unions of Wales (NFU Cymru and Farmers’ Union of Wales).

The scheme looked at the industry and sought to capitalise on already existing structures. One such example is the annual TB test. This allowed the vet to collect appropriate samples while on farm and adding value to the tuberculosis (TB) test. While on farm the vet could (with farmer agreement) take blood samples from 5 animals per management group. Most farms were assessed by their own veterinarian as being a single management group, but a number had multiple management groups.

However, some farms may not quite fit the model for exmaple, if they have sold calves at 6 months, but flexibility in the selection of animals to be blood sampled, or in the timing of the sampling on farm, allowed most farms to overcome the issue.

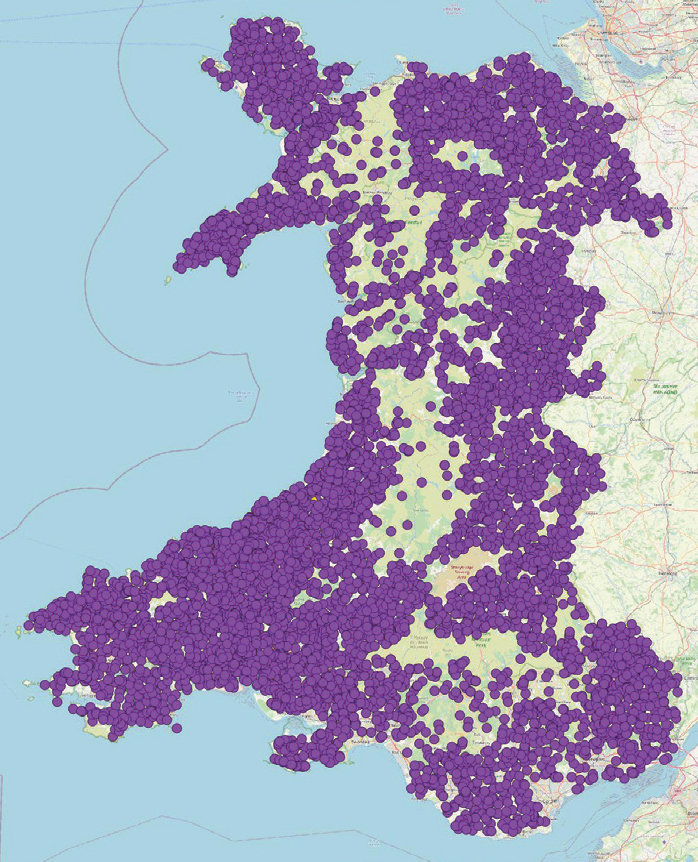

Over the programme 9369 farms had been screened at least once with 5809 farms taking the opportunity for regular annual screening over the lifetime of the scheme (Figure 1).

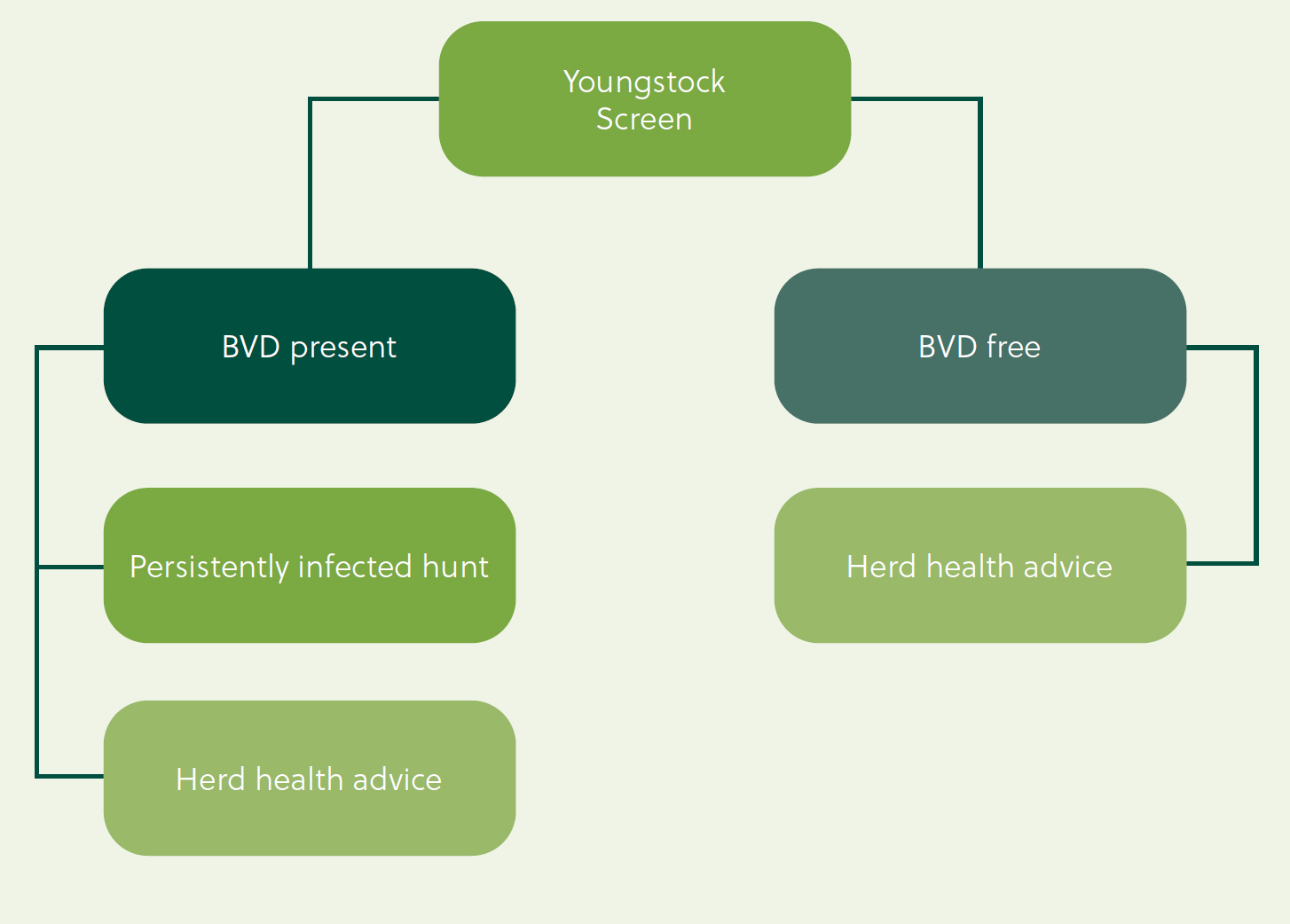

The samples were sent to any of the approved labs and these labs were able to turn around most of the results in under 72 hours. This was something the Gwaredu BVD team worked towards. The quick turnaround aim allowed the vet the opportunity to discuss many issues around disease control with the farmer. The results of the test gave a tangible rationale for discussion of issues such as biosecurity and disease eradication (Figure 2).

The role of persistently infected animals

The check test would determine whether there was the possibility of persistently infected animals on the farm or whether it was free from persistently infected animals. One antibody positive sample was considered as indicative that there may be a persistently infected animal present. The farmer could then be guided by their vet as to the best course of action. The number of farms that were positive was initially 27% and dropped to 23% by the end of the voluntary project.

Where there were no antibodies then the most appropriate advice for the farmer around biosecurity and preventing disease on farm could be given.

Where there was at least one antibody the farmer and the vet were supported financially to find any persistently infected animals on farm. The vet and farmer had a free hand in the approach to the way they detected the persistently infected animals on farm. Ear tags, blood sampling and bulk milk tests were all utilised by vets. Once the persistently infected animals were identified it was the farmers responsibility to deal with them. Gwaredu BVD believe the most appropriate response was immediate slaughter; retention on farm was considered a high-risk activity and inappropriate.

In total, 1296 farms that were positive took the opportunity to find persistently infected animals and 1582 persistently infected animals were detected.

Positives of the scheme

The simplicity of the programme was believed to be key factor in getting large number of farmers involved. The overall process of the Gwaredu BVD model was easy to explain to farmers and other stakeholders, which led to a high degree of compliance. This also allowed a consistent message to be stated to all involved avoiding confusion. This, along with the significant media comms campaign, raised the profile such that farmers were keen to demonstrate their achievements.

To help this and to provide another incentive to become involved in BVD eradication, Gwaredu BVD awarded certificates that demonstrated the number of annual BVD tests that a farm had come back with all negative antibodies. Farmers would ask for and show their certificates when they felt they needed to such as at shows. Markets were also permitting the indication of the status. Farmers had pride in the status and perceived it as having value.

Further indicating industry support, the Royal Agricultural Show decided that BVD free status was an important health criterion and started asking for this status before allowing cattle entry onto the showgrounds.

Limitations of the scheme

While the programme was voluntary, this came with drawbacks that limited, and arguably, prevented it from going as far as might have been hoped and to have the reach that could have been achieved.

The first limitation is that all the farms did not test: while the 85% figure is impressive, the unknown status of the farms that did not test represent a risk to the rest of the industry for reinfection. This gap in the testing, while not unexpected, was a driver for legislation so that no farmer could not be aware of their BVD status.

The fate of persistently infected animals was left to the farmer – this meant that there was no control on what the virus infected animals. These could be sold on to another unwitting buyer. As with other BVD control programmes about PI animals the Gwaredu BVD advice was to send these animals to slaughter as soon as possible. Anecdotally it appears that some farmers were attempting to raise groups of virus-infected animals in small groups. These animals remaining on farms means that the virus is liable to spread from the farm. Once again this is a rationale for introducing legislation to manage the risk of disease spread from farm.

The recognition of these disadvantages was a major driver for the need to put legislation in place.

Legislation

As part of the process of putting the legislation in place, there was a consultation on the concept and manner of the legislation. There were over 100 responses from vets, farmers, unions and other interested parties.

The summary of the consultation responses published in December 2022 (Welsh Government, 2022), with 81% of the respondents supporting mandatory BVD screening of herds in Wales. Over 97% of the responders agreed that the eradication of BVD would benefit the health of Welsh cattle and benefit the farmers in Wales. Overall there was a strong agreement by the respondents to the proposals.

In January, the Minister for Rural Affairs, North Wales and Trefnydd, Lesley Griffiths, in answer to a question in the Senedd indicated that BVD legislation would be in place by the end of the current financial year (2023–24).

The details of the legislation are for the Welsh government to set out in detail, but the consultation suggested that the industry was content with the Gwaredu BVD strategy and it is likely that a programme based on screening for antibodies, with restrictions on farms that have positive antibody results.

Conclusions

Whatever the outcome of the deliberations within Welsh government, the eradication of BVD from the farm is going to be a positive outcome for the health and welfare of the cattle on farm.

Office of the Chief Veterinary Officer (OCVO): statementAs indicated in the ministerial answer BVD legislation is being prepared and the intention is to introduce legislation in this financial year.The OCVO team are working hard to ensure that all the key elements are in place to allow this to be successfully done.The compulsory screen is based on the Gwaredu BVD programme and screening in the 12 months before the start of legislation is likely to be grandfathered into the database. It is therefore recommended that cattle keepers maintain testing as per Gwaredu BVD until the announcement of more details.