The UK government pledged to eradicate bovine tuberculosis (TB) by 2038. The slow progress at the start of the TB Strategy for England prompted a comprehensive review, commissioned by the then Secretary of State, Michael Gove and led by Professor Charles Godfrey (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 2018).

Since its publication in November 2018, much of the content and many of the recommendations for change have been addressed, but few have been actively implemented. Progress is slow.

Some welcome progress has been made, and the official data published in December 2022 shows that the prevalence of bovine TB has fallen in recent years in the country as a whole (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs and Animal and Plant Health Agency, 2022).

There are numerous ways of measuring and monitoring infectious disease, but probably the most direct and relevant is to monitor the rate of new infections. As a basic principle, in live-stock populations that are dynamic and where the animals have a limited lifespan, controlling infectious disease is best achieved by preventing new infections. This focuses the efforts and resources on protecting the uninfected by reducing the risks of transmission and reducing the infective load by removing the reservoirs of infection. Success is measured by monitoring new incidents, either at a population or individual animal level.

In the calendar year of 2021, there were 2866 new herd incidents in England, compared to a peak of 3973 in 2015. There were 665 in 2021 in Wales, compared to 842 in 2015 (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs and Animal and Plant Health Agency, 2022).

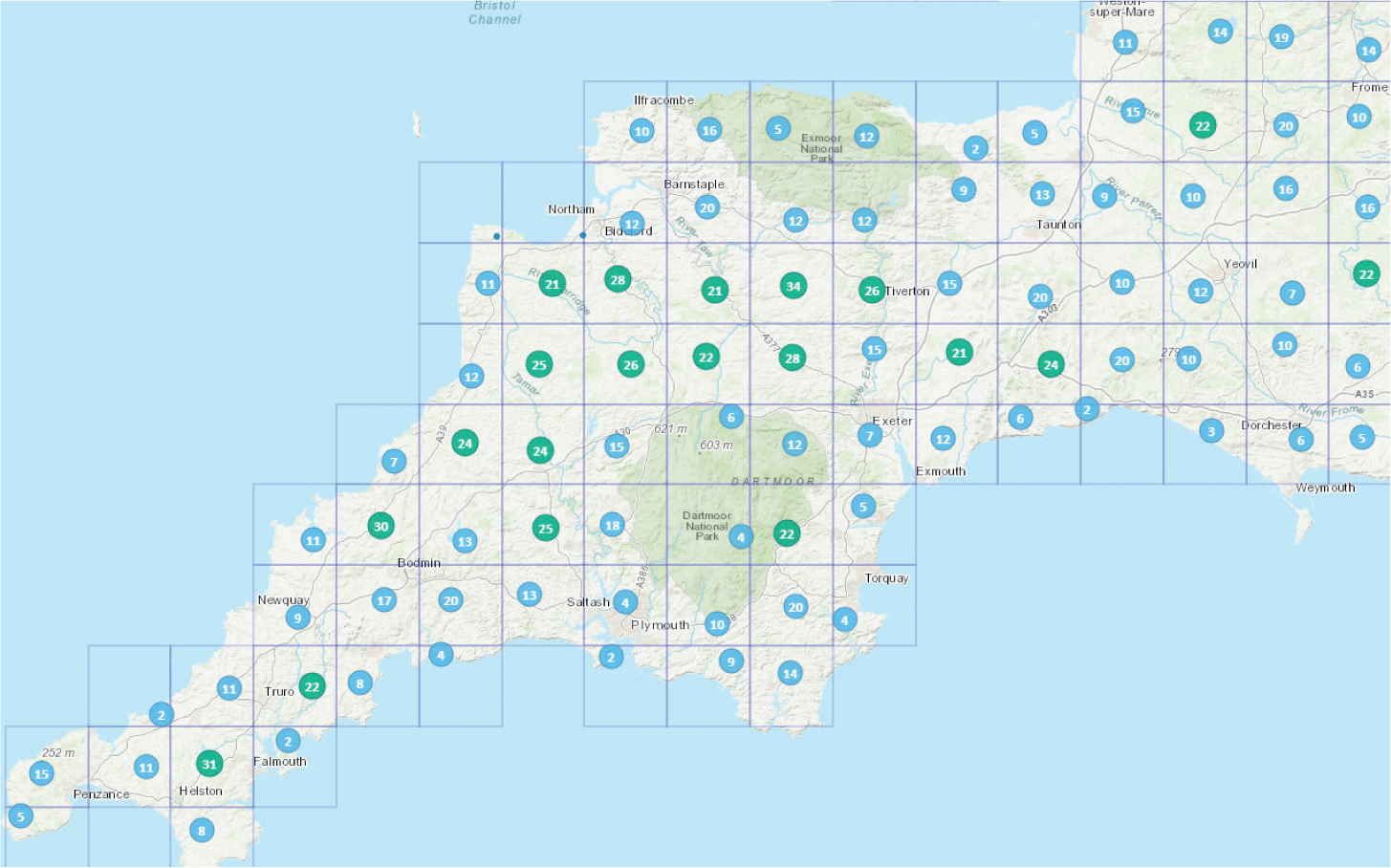

The heartland of bovine TB infections is south west England. A short tour of the excellent map of tuberculosis incidence published by the Animal and Plant Health Agency on behalf of Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (https://www.ibtb.co.uk; Figure 1) demonstrates that Devon and Cornwall consistently show as big problem areas. My own practice is based in mid Devon, and we are not proud of the fact that we have the highest incidence of bovine TB anywhere in Europe.

We are also very concerned that, despite the implementation of strict policies for the culling of wildlife and cattle over recent years, the problem appears to have got worse. In Devon and Cornwall, where over 80% of the land area is now actively involved in badger culling, where we have robust testing programmes including the selective but common use of gamma interferon tests, and where we have spent huge amounts of state, industry and veterinary resources on tackling this problem, herds continue to become infected at an alarming rate. In the year to September 2022, there were 950 new herd incidents in Devon and Cornwall, compared to 772 in the same period in 2021. These represent over 30% of all new herd incidents in England.

Of course, much of this increase may be explained by the increased surveillance introduced last year, where most officially TB free (OTF) herds were moved to 6-monthly testing. These herds were apparently TB free before testing, but lost their status as a result of the discovery of infection through routine testing. They were simply discovered sooner rather than later. The early discovery of infection may help reduce the infective load, but the reality is that the more we look, the more we find.

The current strategy of bovine TB control administered by the state is based on the premise that the causal organism, Mycobacterium bovis, is spread from one infected animal to another, mostly by respiratory transmission. The state-funded test-and-cull programme aims to find potentially infectious cattle and remove them from populations before they become infectious, thus eliminating the source of infection. Known infected herds have statutory movement restrictions imposed to prevent the spread of disease out of the herd. The potential of extraneous sources of infection such as badgers has been addressed in many areas (including over 80% of Devon and Cornwall) by a combination of large scale culling and biosecurity measures to minimise contacts, resourced by the farmers themselves. But there are major gaps in this cooperative strategy which now need addressing.

We need to detect all infected animals as well as herds

The current surveillance programme is adequate for detecting infected herds, but inadequate for detecting infectious animals. The skin test (SICCT; Figures 2 and 3) and gamma interferon tests currently used in various formats, detect a cellular immune response to Mycobacterium bovis. They are specific, but insensitive, and do not differentiate between exposed, infected or infectious animals. Using these tests in infected herds, particularly large herds where there are high risks of spread within the herd, inevitably leaves infectious animals behind, which can become a significant reservoir of infection.

Practically every large dairy farmer has experience of a cull cow being condemned at slaughter because they had multiple TB lesions, which had remained undetected despite numerous skin and gamma tests while in the herd. Better tests for control are needed, with a focus on identifying infectious animals before they get a chance to infect others and contaminate the environment.

Lesions may not reflect severity

There is a belief that the presence of tuberculous lesions somehow reflects the severity of the disease, the chronicity of infection and the level of infectiousness. This has to be questioned. There is a bizarre classification of a TB incident based on whether the disclosed reactors have visible lesions or not. It may be that there are plenty of infected and infectious animals within susceptible populations that do not have lesions, are not disclosed by routine testing and which can shed the organism from various orifices including in faeces and urine as well as saliva and respiratory droplets.

If shedders (be they intermittent or continuous) do exist undetected in herds, the potential for environmental contamination and direct transmissions becomes a major issue on farms where hygiene is a challenge. Simply removing reactor animals may not be enough to prevent new infections.

Controlling infectious disease

There are four pillars that need robust management in order to manage and control any infectious disease (Figure 4):

- Biosecurity is the risk of disease entering a herd or population. Effective biosecurity is hard, but not impossible. We need to understand how the 950 Devon and Cornwall herds that were newly infected in the year to September 2022 became infected, and control those risks. Badger culling does not appear to have had a great effect so far. Environmental risks as well as animal risks have to be tackled.

- Bio-containment is the risk of disease spreading within a herd: it is likely that of the 950 new incidents in Devon and Cornwall, half of them were recurrences of a previous infection which had gone undetected in the herd. In modern, large breeding herds biocontainment is challenging, but livestock farmers have embraced the challenges of Johnes control by effectively measuring and managing the major bio-containment risks to prevent new M. avium paratuberculosis infections: it can be done.

- Surveillance for control is the detection of infection. This needs a total rethink, with a wider use of better, novel testing systems including the use of alternative tests such as the Idexx ELISA test, Enferplex antibody tests and Actiphage tests for the presence of the organism. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests are widely used to detect human tuberculosis, caused by M. tuberculosis. Similar tests are available to detect M. bovis, but their use in the UK is currently restricted to confirming the presence of the organism in post-mortem samples: there is an opportunity to use these tests more extensively to detect infection and environmental contamination. Caudal fold tuberculin tests are cheap, easy to use and sensitive, and widely used elsewhere in the world.

- Resilience is the resistance to infection. Resilience is not just immunity, and not only a matter of vaccination. The cattle version of the commonly used human BCG tuberculosis vaccine is coming, but the practical use of this vaccine in field situations still needs to be devised. Where, how and when it is to be used has yet to be determined, and the efficacy in preventing new infections is not yet fully known. It may be several years before this hope may be fulfilled. The mechanisms for bovine TB transmission and the progression from exposure to infectiousness need exploration and review, focussing on preventing the spread of disease by managing resilience (hopefully by vaccination) at the most appropriate times, particularly in the fresh calved cow and neonate.

There are over 71 000 cattle herds in Great Britain registered on the Animal and Plant Health Agency database. Of these, fewer than 1500 fall in to the category of being persistently infected (those having their OTF status suspended or withdrawn for more than 18 months) or recurrent (a breakdown within 3 years of a previous breakdown). It is highly likely that these problem herds are the main reservoirs of infection in the national cattle population: chronically infected herds spreading disease within themselves and to others and contaminating the environment. These herds, mostly large dairy herds, need special attention. A robust TB management programme targeted at these problem herds, where all four pillars of disease management are properly addressed, could accelerate progress. Engagement of all parties including the state, the farmers and the private vets will be needed to bring about any rapid improvement in TB control.

KEY POINTS

- The strategy to control and eradicate bovine tuberculosis is progressing, albeit slowly.

- Progress in the south west of England, the heartland of bovine tuberculosis, is disappointing: it is getting worse.

- New technologies are available, particularly for the detection of undisclosed infected animals, and should be used.

- Testing alone will not solve tuberculosis: a comprehensive programme of infectious disease management engaging all parties needs to be targeted at the problem herds.