Johne's Disease (JD) in cattle remains a significant challenge to successfully resolve at a national level. The causative organism Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP) has a long incubation period and a wide range of risk factors for transmission and each farm requires its’ own specific management plan. The risks of MAP entry and transmission were historically high in the UK (Sibley and Orpin 2012; Orpin, 2014) and the success of JD control requires a robust commitment for several years before the prevalence reduces.

In 2009, Dairy UK (the national organisation representing milk processors in the UK) established Action Group Johne's (AGJ) to tackle the rising incidence of JD in UK dairy herds. Over the ensuing years, the National Johne's Management Plan (NJMP) was developed through AGJ based on the basic and generic principles of infectious disease management. The foundations of the programme were based on experiences established by the successful Southwest Healthy Livestock Programme, which ran between 2010 and 2013 (Sibley, 2024). The JD framework intended to encourage farmers and veterinarians to work together to identify the likely risks of JD introduction and transmission, followed by creating a bespoke control plan based on one of six control strategies, together with appropriate control points, which would be adhered to by the farmer (Orpin, 2017; Orpin et al, 2020a). The adoption of the voluntary NJMP was encouraged by AGJ stakeholders including; milk processors, retailers, milk recording organisations, farming groups and veterinarians. The level of engagement with the NJMP was high and peaked in 2018 with 6084 dairy farmers submitting NJMP declarations (Orpin et al, 2022). Since 2019, completion of the NJMP or an equivalent scheme has been mandatory under the Red Tractor (2021) assurance scheme. Thus, JD control plans are created annually by 95% of UK dairy farmers. In 2022, this trans lated to approximately 7125 dairy farmers in Great Britain (GB) (based on AHDB data which estimated that there were 7500 dairy farmers in GB in 2022).

In 2021, the JD Tracker tool was developed by PAN Livestock Services and Veterinary Epidemiology and Economics Research Unit (VEERU, University of Reading), with input from the AGJ (Orpin et al, 2022; Taylor et al, 2024). The JD tracker tool aimed to identify potential outcomes and driver measures to track JD progress. Subsequent developments of the JD Tracker tool has allowed farmers and veterinarians to track the progress of infection and control over time and compare their progress with their peers within 253 herds who use the individual milk ELISA on a quarterly basis (Orpin et al, 2020a). Analysis of 154 herds over 10 years has demonstrated a wide variation of JD outcome measures and drivers in JD progress, herds in the worst quartile based on their average test value showed little progress with new detections, removals and service of known infected cows, despite their investment in individual milk ELISA testing. The refractory herds appeared to be tested regularly but failed to effectively manage the disease (Taylor et al, 2024). This article explores potential communication and motivation strategies that Johne's advisors and veterinarians can use to engage farmers with effective JD control through a clearer understanding of the barriers and solutions to effective engagement.

Methods

This article uses a mixture of academic literature and expert opinions to establish common reasons for the success or failure of farmer and veterinary engagement in disease management programmes, with a focus on JD. Firstly, an initial search of academic literature was conducted by searching for the following keywords in online databases (Scopus, PubMed and Web of Science); ‘Johne's’, OR ‘paratuberculosis’ OR ‘Mycobacterium paratuberculosis’ OR ‘Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis’ OR ‘Mycobacterium avium ssp’ OR ‘endemic diseases’ OR ‘bovine disease’. Next, to narrow the search to academic literature which specifically related to the management of endemic bovine disease within national or regional control programmes, the following keywords were searched for in the academic literature; ‘manage’, OR ‘control’, OR ‘strategy’ OR ‘programme’ OR ‘behaviour’. Papers included in the search had to be published after 2010 and based in middle- to higher-income countries, such as Europe, Canada and New Zealand. In total, 18 pieces of academic literature met these criteria.

Secondly, expert opinions were sought from industry leaders, including, experienced dairy veterinarians, members of Action Group Johnes (AGJ) and attendees of the International Dairy Federation Forum 2022 and International Colloquium on Paratuberculosis 2022.

Results

The key areas that will influence the likely farmer engagement with Johne's Disease can be usefully divided into five overlapping areas: attitudes and beliefs, practical challenges, veterinarian-farmer relationship, industry drivers and scheme design.

Farmer attitudes and beliefs

As summarised in Figure 1, farmer decision marking is driven by multiple factors. The farmers’ attitudes and beliefs have a marked influence on how they rank the importance of the adoption of a JD programme.

A comprehensive narrative review focusing on the determinants of farmers’ adoption of management-based strategies for infectious disease control (Ritter et al, 2017) revealed that farmers will make management decisions based on their unique circumstances, agricultural contexts, beliefs and goals. Providing farmers and herd managers with rational but universal arguments might not always be sufficient to motivate changes in animal husbandry and management, and investment in animal health.

A key study (Ritter et al, 2016), focusing on detailed interviews with 25 farmers in Alberta, revealed that farmers could be categorised into proactivists, disillusionists, unconcerned and deniers based on their beliefs and importance with controlling JD in their herds. This system of categorisation was explored in a non-random survey of 394 dairy farmers in the UK (Orpin et al, 2017) 78% of the respondents considered themselves firm believers in JD control (‘proactivists’) and would recommend it to other farmers. A total of 22% of farmers were defined as ‘unconcerned’ and although they believed in Johne's disease, they did not see the disease as important enough to control. Nearly 50% of the unconcerned group wanted more evidence that JD control works compared to 21% of the proactive group.

Sorge et al (2010) undertook a study exploring the attitudes of 238 Canadian dairy farmers to JD risk assessments and proposed management changes. The key barriers to the adoption of controls were the lack of belief that the changes were necessary and the practical space limitations on the farm that were perceived to be needed to implement husbandry changes in accordance with the control plan.

The practising veterinarian must clearly identify what the farmers’ beliefs and attitudes to control are before progressing with any advisory work. This can be achieved by using a series of open questions exploring the importance of the disease, any perceived barriers and benefits/costs of control

Veterinarian-farmer relationship

This complexity of decision-making was also identified in a detailed qualitative study by observing the advisory consultations between 14 farmers and veterinarians in the UK (Bard et al, 2019). The relational context of trust, shared veterinarian-farmer understanding, and meaningful interpretation of advice at a local (farmer) level that was most likely to enact change. Each component was important, and they acted synergistically.

A UK study of 10 cattle farmers’ and 10 veterinarian's attitudes to biosecurity (Grant et al, 2023) revealed five interconnecting themes, focused on issues of trust, time, getting to know each other, the ability to have cooperative discussions and clarification regarding the cost-effectiveness of measures. This relationship and potentially how these interactions occur are likely to be critical to any future disease prevention planning and implementation efforts.

The importance of the relationship with the veterinarian was highlighted in another UK study where five themes were identified that impacted the willingness of farmers to adopt biosecurity measures: trust, time, getting to know each other and clarification of biosecurity cost-effectiveness and cooperative discussion (Grant et al, 2023).

In 2023, a detailed social science project in the UK, exploring the barriers to the adoption for Johne's Control, was undertaken with 418 farmers and 154 vet professionals via 22 JD workshops (Morrison et al, 2024). More detailed interviews were conducted with 15 farmers who were not engaged with JD control as well as 13 veterinarians. Four major barriers were identified to engagement: expectation management, space and economics, free rider problems and veterinarian-farmer relationships. The important sub-themes were JD control never ends, the complexity of data is confusing, limitations of space to segregate, unproven economic benefits, dangers of buying in cows, and inappropriate JD scheme design. There were also issues with veterinarians not being proactive, with a lack of understanding of farmer priorities and insufficient communication skills.

The further education of veterinarians to enable them to communicate more effectively with less engaged farmers is essential. Unless understanding, beliefs and barriers are explored it is unlikely a successful JD programme will be developed.

Practical challenges and education

A social science multinational literature review (Morrison and Rose, 2023) highlighted five key barriers to JD control:

The top three problems revealed in a survey of 394 farmers within the UK, with JD control, related to challenges of segregation of high-risk animals (53%), tuberculosis testing interfering with results (40%) and uncertainty on when to cull test positive cows (38%)

There are any number of reasons that can be used to prevent progress with control at an individual farm level and these must be gently exposed during the consultation.

The most popular control programmes in the UK are those that involve improved farm management (IFM) in combination with either strategic testing or culling (Orpin et al, 2020a). The ELISA test is used repeatedly to detect the level of MAP antibodies present in milk and provides farmers with a test result that is based on standardised laboratory sampling and testing. Jordan et al (2020) found that test results that show variable levels of MAP antibodies were confusing for farmers who were more familiar with making decisions based on binary positive or negative test results. This was also confirmed by a survey in the UK (Orpin et al, 2017; Morrison et al, 2024).

Considerable time and effort are required on the part of the advisor to reassure the farmer of the complex issues surrounding the interpretation of test results to ensure disillusionment does not limit progress. Farmer education and extension work is important to demystify misconceptions and to enhance engagement.

Industry drivers and scheme benefits

Financial incentives from milk processors were the strongest driver for engagement. Within the previously described non-random survey of 394 dairy farmers in the UK, there was little evidence of deniers and disillusionists in this survey although recruitment bias may have underestimated the results (Orpin et al, 2017).

The relatively low level of adoption of the Irish Johne's control program (Gavey et al, 2021) was thought to be related to low levels of intrinsic drivers to take part, unconvincing cost benefits within low prevalence herds and the long-term commitment required to achieve results. Providing subsidised testing is not enough to overcome the barriers of engaging with a JD scheme.

A study of 17 dairy farmers and seven veterinarians exploring the drivers of engagement with JD in the UK (Robinson, 2020) were influenced by the quality and enthusiasm of veterinary advice, understanding of the economic costs of the disease, the presence of the national voluntary JD plan and a fear of a potential future food scare if a zoonotic link were proved. The threats of reputational harm and market loss have strongly influenced farmer and veterinary behaviour in the UK together with the compulsory involvement of supplier farms to retailers and processors. The economic benefit of control is an important area to consider with Johne's disease as many of the losses are subclinical.

For JD control to be effective the farmer must not only believe the controls will work, consider them important enough to deploy and also maintain that input over several years. Full engagement is essential for success.

The role of the milk processors and retailers has been important in creating momentum for continued engagement and has been a key driver within the UK. The creation of a National Programme with incentives to join is not enough to achieve effective engagement at a national and farm level.

Multifactor influence and NJMP design

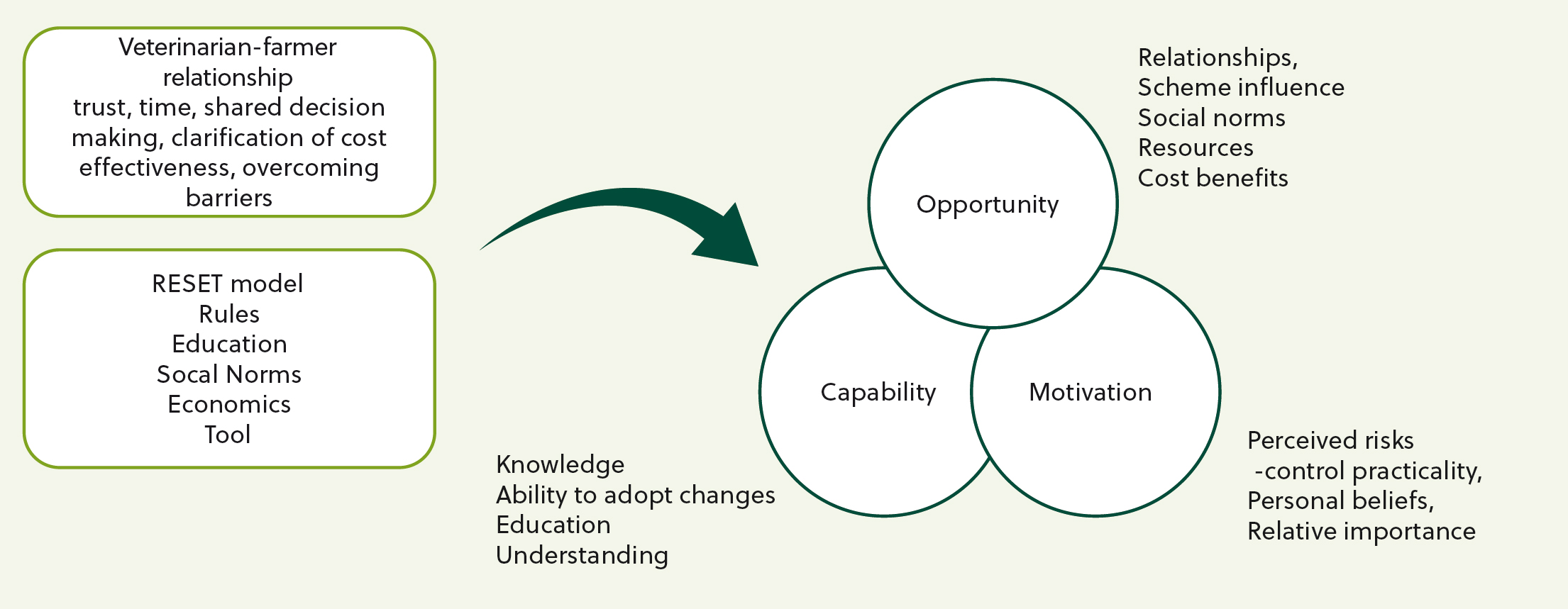

A comprehensive review of the literature analysing farmer behaviour and their decision making (Biesheuvel et al, 2021) showed that farmer behaviour was influenced by a combination of personal beliefs, interpersonal relationships and wide variety of contextual elements (incentives, schemes, national programmes). This could be further analysed at an individual farmer level as capability (knowledge, ability to change, education), opportunity (relationships, farmer-government/scheme influence, resources, cost benefits etc) and motivation (perceived risks, control, practicality, beliefs, importance etc). In essence, the factors are interlinked. Each factor has an impact on the other and that must be appreciated by both the veterinarian and the farmer.

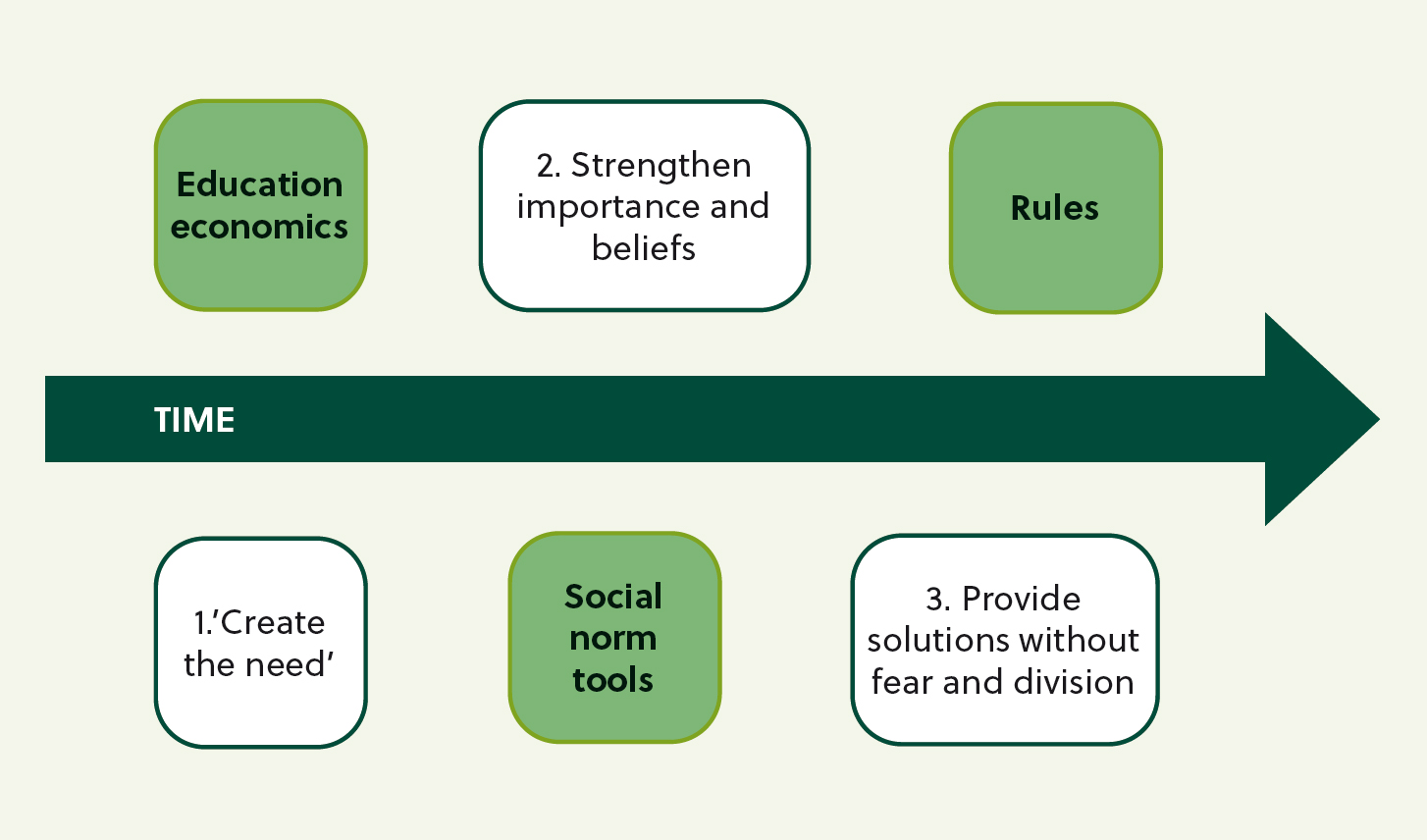

Within the NJMP framework, the RESET mind model was adopted as the methodology from work in the Netherlands to reduce antibiotic use in farmed livestock (Lam et al, 2017). This model suggested that for success, all five elements of the programme should be deployed simultaneously for maximum effect. The adoption of the RESET model (Rules, Education, Social Norms, Economics and Tools) has allowed for widespread inclusion of farmers within the NJMP as well as other national disease programmes. This was modified and rearranged to ensure the Rules element was delayed, maximising farmer engagement (Orpin and Sibley, 2018) [AQ: no in reference list] (Figure 2). This same methodology can be applied within a veterinary practice setting. Explanation and understanding are crucial to the adoption of the programme.

How can this researched be applied to help improve veternarian practice JD programmes?

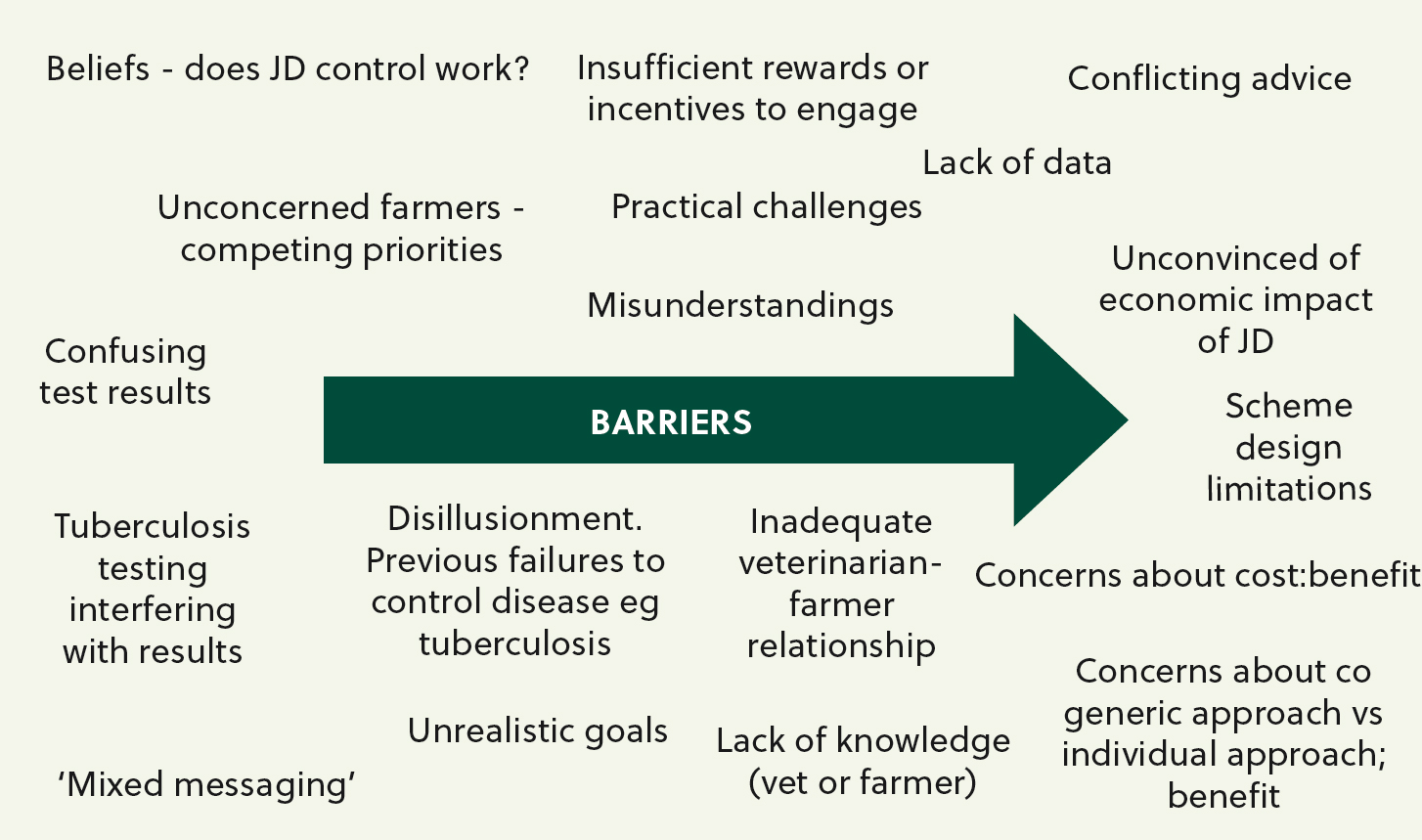

The barriers to control are complex and are highlighted (Figure 3). The skill of the veterinary advisor is to explore what is constraining the farmer to engage.

The conclusion is that if progress is to be made with JD control, there is no single approach that will work, and which will result in success. This is clearly why, historically, prescriptive and inflexible national programmes have often failed. In many situations, a single ‘rule-constrained’ control strategy is imposed on the farmers with limited help to engage farmers with the programme, apart from subsidising tests.

Each participating farmer will have their own beliefs that have to be understood and their own biases and opinions on the disease. This is particularly relevant if seeking to manage the late adopters or to engage reluctant farmers who may simply need a different communication method to motivate them to take part in the programme.

The veterinarian-farmer relationship is key to progress and the approach adopted should be altered according to the farmers’ knowledge, attitudes, experiences and circumstances. The key factors. challenges and solutions are highlighted in Table 1. These range from relational factors, barriers, practical limitations, economic priorities, scheme design, farming systems and attitudes to risk. A considerable amount of listening and conversations may be required to understand the farmers’ attitudes to JD control.

| Key factors and references | Challenges | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Relational factors (Bard et al, 2019) | Trust, shared veterinarian-farmer understanding, and meaningful interpretation of advice at a local (farmer) level | Tailored advice based on trusting relationship, shared understanding of farmers, priorities, drivers, motivations and goals |

| Determinants of adoption infectious disease control and human factors (Ritter et al, 2017) | Barriers are highly personal based on beliefs, contexts, goals, circumstances, not necessarily rational | Personal approaches, group work, peer to peer learning, cost vs benefit shared discussions, making processes simpler and effective, consistent messaging |

| Practical factors (Orpin, 2017; Sorge et al, 2010; Orpin et al, 2020bJordan et al, 2020, Morrison and Rose, 2023) | For example: test results confusing, segregation too difficult, tuberculosis test interference | Farmer/veterinarian education, repeat sampling, discipline, creative approaches to reducing transmission (green cow and calf lines) |

| JD scheme design (Morrison and Rose, 2023; Morrison et al, 2024) | No end point with control, data, disease complicated | Common approaches to disease control, define realistic expectations, improved communications, simplicity of data sharing |

| Economics (Ritter et al, 2017; Gavey et al, 2021) | Cost benefit of control, who benefits? Incentives, economic impacts in low prevalence herds? | Better communication of overall health, financial improvements, production, improved market opportunities, less worry |

| Farming systems (Morrison et al, 2024) | Buying in infected cows, individual vs collective benefits (free rider problem), herd sizes and risks of spread | Improved explanation of disease transmission and disease dynamics |

| Zoonotic risks (Robinson, 2020) | Perceived impact on human health and consumer impact on industry should a link be proved | Continued communication, sharing research and encouraging participation in JD control as a precautionary approach |

What can we do at a practice level to help improve farmer engagement?

Success with JD control is highly dependent on both veterinarian and farmer. Where programmes can stall in veterinary practices is through a didactic following of a singular process to engage the clients. The NJMP involves engaging the farmer in one of six solutions to meet their needs. There is sometimes a tendency for veterinary teams within commercial practices to latch onto a single strategy as their preferred way to manage JD and a rigorous attempt is taken to incorporate all clients into the same strategy irrespective of clients’ needs and resources.

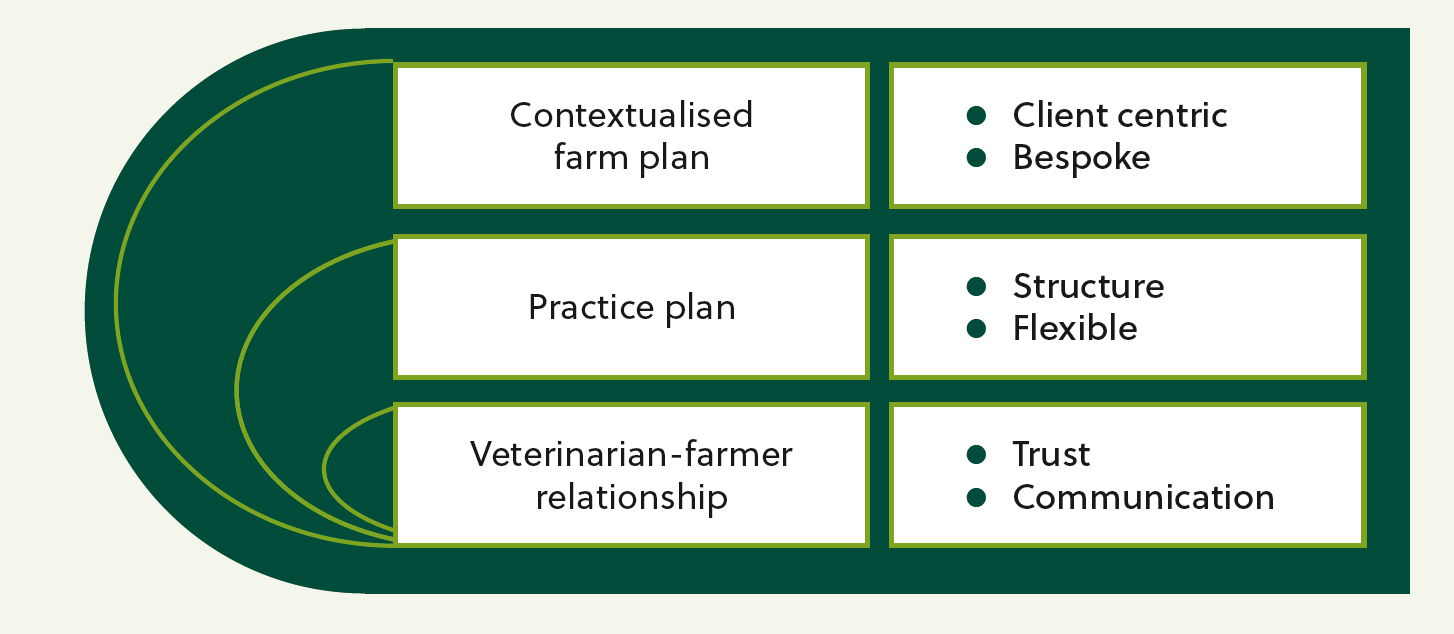

To succeed, the whole practice team must take the farmers through a process of understanding and actions, spanning many years, which engages the farmers with effective JD control. The core elements required centre around developing a strong veterinarian-farmer relationship, a structured practice approach and the contextualised delivery of the plan at farm level.

A listening and coaching methodology is often more compelling than a traditional expert-led or didactic approach. If solutions are proposed the farmer will often challenge the solution. If a problem is shared the farmer will commonly find an agreed solution themself and this will be more widely adopted on the farm.

Directive paternalistic communication styles typically adopted by a busy farm veterinarian are less likely to encourage participation and avoid exploration of the barriers or fears that the farmer faces (Bard et al, 2017). Motivational interviewing based on empathy, collaboration and establishing client autonomy is a useful approach to adopt. The Health Belief model and the Stage change model have been adapted by Higgins and Green, 2012 and Higgins et al, 2012 to illustrate the process that should be undertaken to help motivate a farmer to change their behaviours and engage with change (Figure 5).

Using individualised client advice and approaches

Within a practice, there are a range of differing client types. The farmers that are early adopters are typically ones that have a good relationship with the veterinary practice. They read the newsletters, attend meetings and are willing to trust the advice provided by the veterinarians and other advisers within the practice. Simply persisting with the same communication model may not be effective in helping manage those farmers yet to engage.

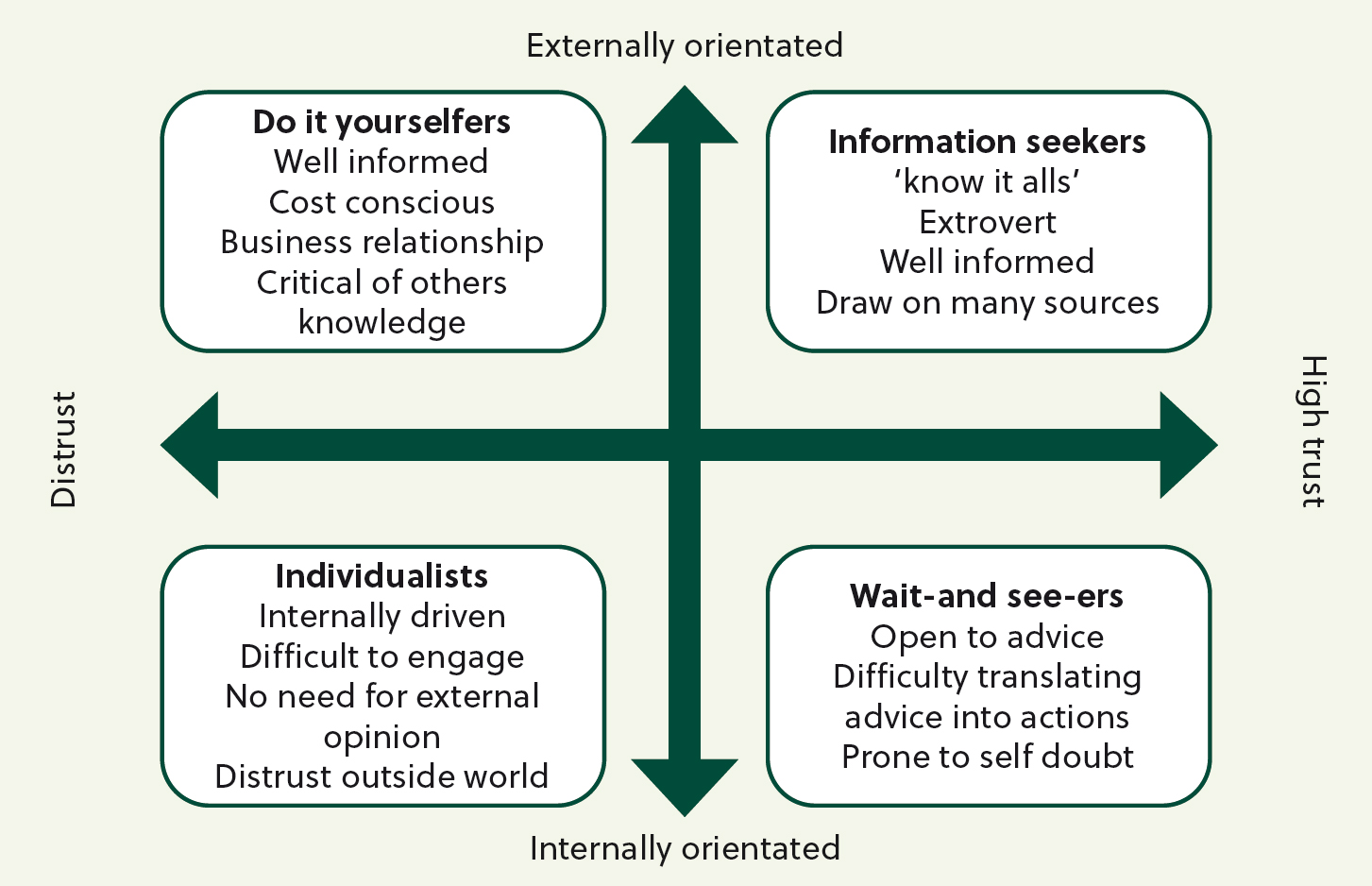

For those in commercial farm animal veterinary practice, it must be accepted that not all farm clients are the same and they have differing learning styles, with differing levels of understanding of technical issues and trust in the advice they receive. Therefore, the method of communication must be altered to consider the clients’ beliefs and attitudes (Wessels et al, 2014). Four differing client types (Figure 6) were identified within what the vets described as ‘hard to reach’ farmers.

Each client type requires a subtley different approach and the inflexibility of communication methods may lead them to be believed as ‘hard to reach’. These are:

Once engaged, it is essential to coach and support the farmer to give them confidence to progress. Kolb's learning styles based on the persons understanding and knowledge similarly divided the population into Activists, Reflectors, Pragmatists and Theorists (Wessels et al, 2014), emphasising that appreciating how the farmer thinks really does help with communication and engagement.

How can an effective veterinary practice JD schemebe set up?

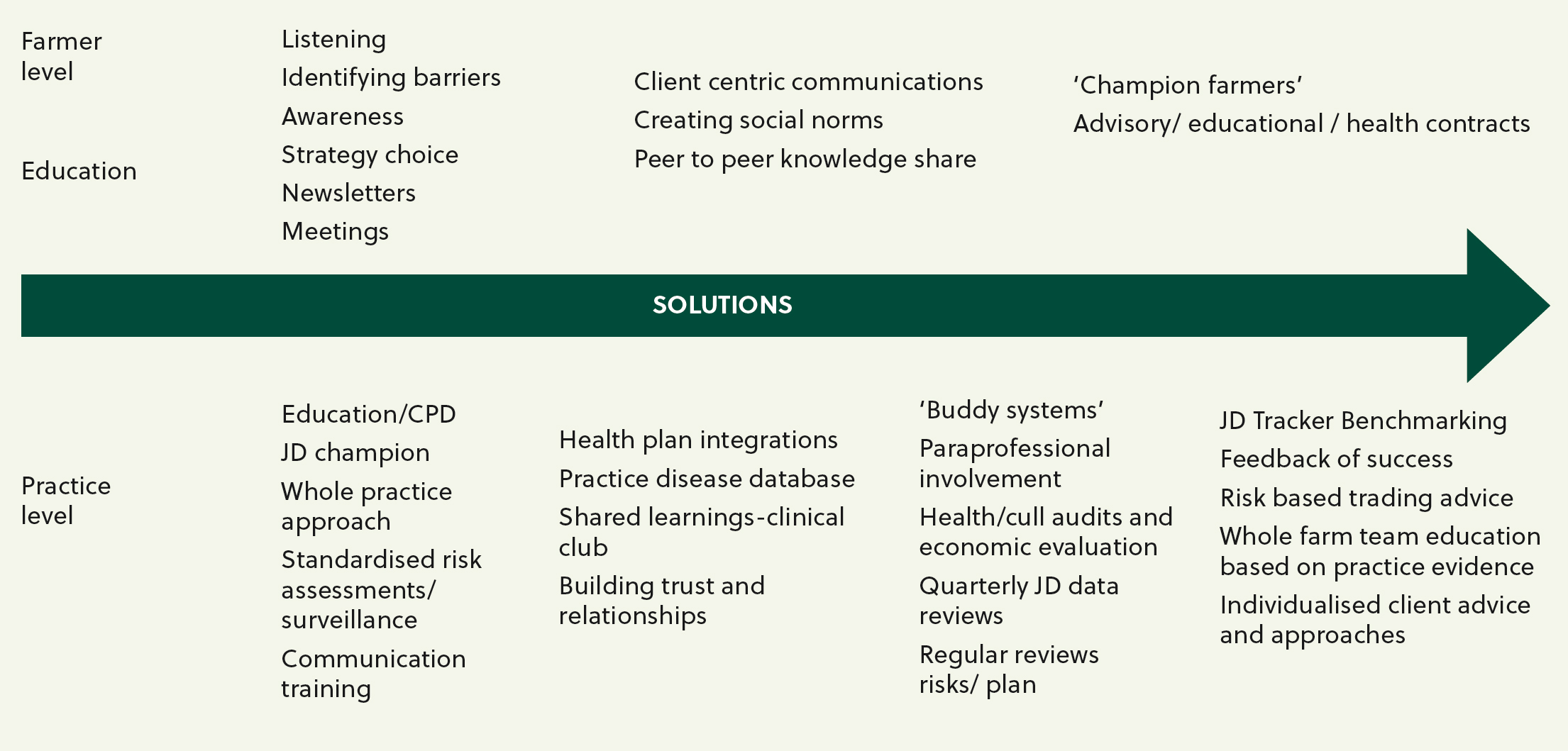

The individual barriers to progress can be overcome by developing solutions both at the farmer and practice level (Figure 6). Both are equally important to embrace.

The process generally starts with veterinary education and developing an agreed approach to JD management within the veterinary practice. Common messaging is very important and any concerns or differing opinions that individual veterinarians may have must be managed before the programme is communicated to the farmers. Identifying a ‘Johne's Champion’ or JD lead is a commonly used method. This allows for consolidation of expertise and a sharper focus within the practice. The veterinarian-farmer relationship is also critical. A highly knowledgeable, motivated veterinarian with the right communication skills can engender trust and achieve progress. The human elements are as important as the technical aspects of control, as behaviour change is key component of successful JD control.

If the concepts of the RESET model are deployed the Education, Social Norm and Tools elements are embedded early in the process. Economic benefits where appropriate and the Rules aspects are achieved using the highly flexible NJMP.

On a practice level, a simple 10-point strategy can be adopted to develop a rigorous JD management plan for the practice. The success of this approach will depend largely on the quality of the veterinarian-farmer relationship and the ability to adapt the practice programme to match the needs of the client.

Conclusion

Johne's control within the UK is entering a mature phase. The easy clients to influence have already engaged. Those farmers yet to engage or those who are only partially engaged require differing methods of communication and approaches if further progress is to be made. The limitations on progress are often perceived to be technical challenges such as the insensitivity of testing or the economic benefits of control, but the available tools are adequate to control JD. The focus needs to be redirected to finding client-specific interactions that explore barriers and solutions to their approach to JD control. The development of the NJMP using multistakeholder working, has proved to be the foundation of effective JD control in the UK. Further research is required to fully understand what the challenges for the worst quartile herds are and how best these can be engaged to control the disease better.

Further training for veterinarians and advisors to help achieve this aim would accelerate progress of the NJMP in further reducing JD within the UK.