The role of farm animal veterinary surgeons in the UK is a diverse mix of individual animal treatment, herd health planning, preventative medicine and public health. Although historically large animal medicine was the basis for the veterinary profession, the rising urbanisation of the country and increase in companion animals has led to a change in veterinary careers post-graduation, with the 2019 Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons Survey of the Profession showing only 3.2% of veterinary surgeons working in farm or production animal practice (Robinson et al, 2019).

Recruitment and retention of veterinary surgeons in the farm animal sector is of vital importance to the health and welfare of animals and humans, helping to secure public health through stable food supply chains. Retaining veterinary surgeons involves addressing reasons that veterinary surgeons leave the profession (Adam et al, 2019), as well as supporting newly qualified practitioners to gain the skills and knowledge required for a robust and long-lasting professional career. Farm animal veterinary internships are one way for recent graduates to gain a supported and structured entry into the profession. These internships are offered by both university farm departments and some commercial practices, and they appear to be primarily aimed at new or recently graduated veterinary surgeons. There are no set requirements for farm animal veterinary internships; however, they usually advertise a gradual introduction into clinical practice and more support than is traditional for newly graduated vets. This may take the form of mentorship from a senior clinician in addition to an increase in continuous professional development compared with regular practice allowances. This internship model has been used more commonly in equine and small animal specialities and is normally a step required before specialisation in those fields.

Although individual programmes may gain feedback from previous interns, there is little published literature about the reasons that aspiring farm animal practitioners opt to complete internships, and how their experiences vary as a result of different internship providers in the UK. This study established the common drivers for veterinary surgeons to complete internships in farm animal practice, alongside their experiences during the internship, and their outcomes in the profession after completion.

Materials and methods

A questionnaire was created using a proprietary online survey tool (Jisc Software Package, Bristol, UK). The questionnaire comprised 14 questions with a range of free text and multiple-choice questions. The target population was veterinarians who had under-taken a farm animal internship within the UK. The survey was available online between June and August 2021, and was voluntary to complete. It was distributed via social media (Facebook, Twitter), local veterinary practices (selected by convenience sampling) and veterinary universities in the UK. The questions can be found in Appendix 1.

Results of the survey were exported from the online software into Microsoft Excel 2016 for analysis. The open question answers were categorised into themes using thematic analysis methodology (Attride-Stirling, 2021). Data analysis was performed using SPSS (Version 26, IBM). Descriptive statistics were computed for each question to determine the frequency distribution of the outcomes, with means and corresponding standard deviations calculated for continuous variables. Pearson's chi-squared tests were performed to analyse the relationship between answers. The significance level was set at P≤0.05.

Ethics approval

Ethical approval was provided by the Royal Veterinary College Social Sciences Research Ethical Review Board (URN SR2021-0150), with all data being anonymised.

Results

There were 30 respondents to the survey, all of whom had under-taken their internships between 2008 and 2021. The exact number of internships available over this time period is unknown, but an estimate of 10 internships per year for the 13-year period would suggest a 23% response rate. There were responses from graduates from six UK veterinary schools and one international veterinary graduate. Of the respondents, 40% (n=12) of veterinary internships were undertaken in a purely commercial practice and 60% (n=18) were undertaken in a university. Most respondents completed their internships directly after graduation (96.6%, n=29), meaning it was their first position as a practicing vet.

The main motivation theme found for completing an internship was classed as ‘support’, which was supplied as the motivation or one of the motivations in 63.3% (n=19) of responses. Other motivations were the reputation of the practice or university offering the internship (36.7%, n=11), the exposure to cases and experience available (26.7%, n=8), the structure offered by the job (23.3%, n=7), the amount of continuous professional development offered (20%, n=6) and the availability of a mentor (13.3%, n=4). Other reasons supplied for undertaking an internship included the ability to complete research, continuing links with a university, the requirement of completion for future specialisation (usually a residency programme) and recommendations from previous interns.

The most common scheduled contact time with a mentor during the internship was weekly or fortnightly, and there was a significant relationship between the amount of mentor contact time and if the intern felt this was sufficient (P<0.05). Interns who received contact monthly (30%, n=9) were most likely to report this as insufficient. The amount of continuous professional development offered as part of the internship varied from 5 days to 26 days per year, but despite the wide range in answers most felt the continuous professional development offered was sufficient (96.5%, n=28).

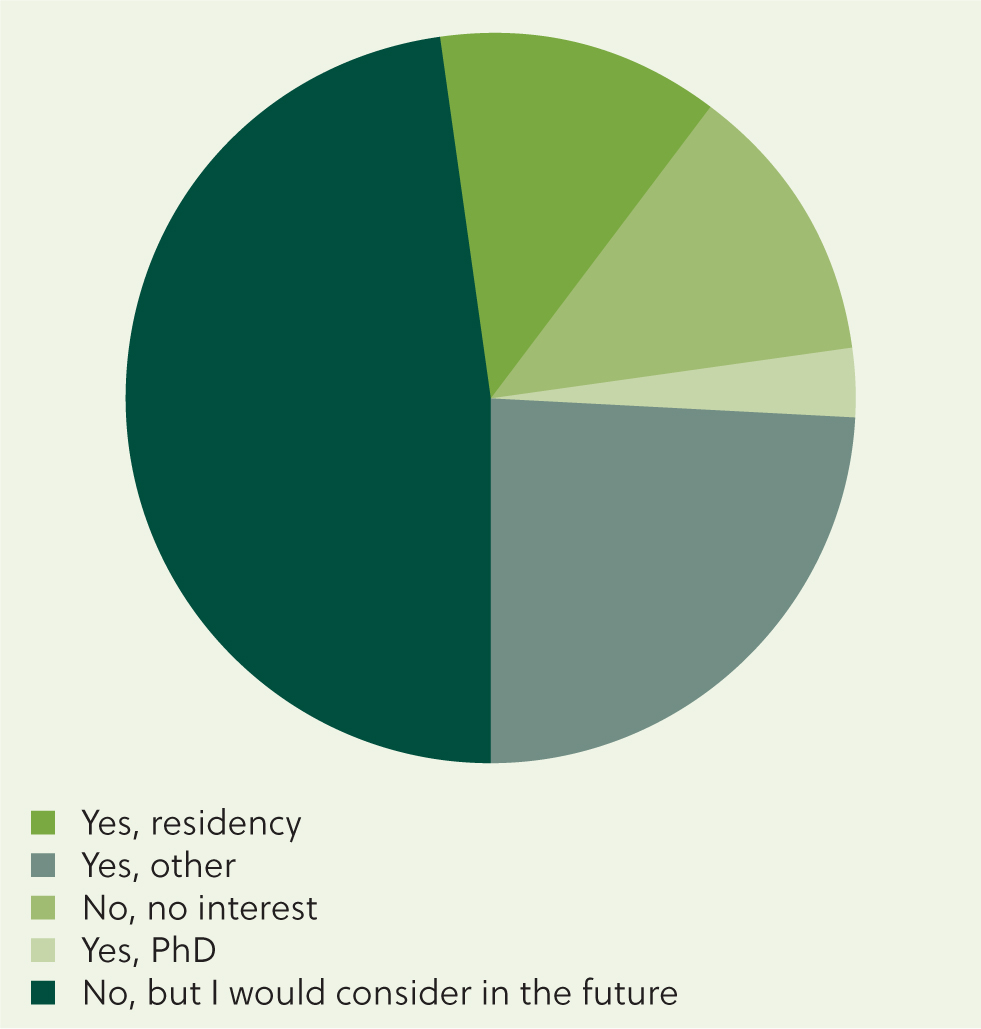

Further education has been conducted in some form (PhD, residency or other) by 37.9% (n=11) of respondents following completion of the internship, with a further 48.3% (n=14) stating that they would consider further education in the future (Figure 1). There was a trend towards internships being completed at a university and the intern then going on to complete a PhD or residency (P=0.067), suggesting working in an academic environment can help to maintain interests in continuing educational programmes.

If given the opportunity again, 89.7% (n=26) of respondents would opt to complete the same internship, with the remaining 10.3% (n=3) opting to undertake an internship different to the one they completed; no respondents reported that they would not complete an internship at all. The majority of respondents 96.6% (n=28) would recommend their internship to other newly graduated veterinary surgeons.

Most of the respondents (96.7%, n=29) reported remaining as a practicing farm animal veterinary surgeon after completion of their internship, with only one respondent no longer practicing, citing the lack of clear progression as their reason for leaving.

Discussion

This study has shown that farm animal veterinary internships appear to be well received by those who have completed them, with most respondents willing to recommend their internship to others. The most common time for internship completion was straight out of undergraduate training, which highlights their possible role in transitioning newly qualified veterinary surgeons into practitioners. Despite the small number of respondents, the feed-back for the internships was largely positive.

The motivations for undertaking an internship centred primarily around the desire for support. This could either be because newly graduated veterinary surgeons do not feel that they will get sufficient support within primary care clinical practice jobs, or that undergraduate students who feel they need more support opt to complete an internship. With the new Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons (2023) requirements for practices with newly qualified veterinary surgeons to complete the veterinary graduate development programme training and provide greater support, this may alter the demographic and motivations of students who complete internships.

The role of a mentor in clinical practice has been explored as a method of supporting new or recently graduated veterinary surgeons during the start of their career. Interns who had contact with their mentor weekly or fortnightly reported that this was adequate, however, interns with monthly contact were more likely to report that this was insufficient. This result should highlight to internship providers the importance placed on regular contact time by the participating interns. Although there were several respondents who had completed the same internship, the replies as to how much scheduled contact time with a mentor was made available varied. This could be attributed to variation within internships or differing mentor approaches; what some mentors would consider contact time may not be considered so by the intern. It is of use to note this variation in experiences as this may influence intern satisfaction in the programme.

Of the respondents, 20% (n=6) suggest that continuous professional development was a motivating factor in undertaking their internship. There was a wide range in the amount of continuous professional development provided during the differing internships – between 5 and 26 days across a year. Despite this variation, most of the interns felt that the amount of continuous professional development offered was sufficient 96.5% (n=28), which may highlight that this is less of a driving factor for internship satisfaction. As all the internships were completed by recently qualified veterinary surgeons who should have been taught the most up to date information during their undergraduate teaching, this may support the idea that they require consolidation and training in putting their knowledge into practice as opposed to more learning (Routly et al, 2002). This application of knowledge may be more easily taught by a mentor than at formally organised continuous professional development events. This study did not explicitly ask about the content of the continuous professional development offered by internships which may meet these demands. Further investigation into the continuous professional development content most required by recently graduated veterinary surgeons may be useful to ensure these needs are met.

The requirement of internship completion for further training was only mentioned as driver for one intern. However, 37.9% of respondents had completed some form of further qualification (PhD, residency or other) following completion of their internship programme. It would be useful to compare this finding to other sectors which may have more stringent requirements for internship completion to allow for specialisation.

Conclusions

The feedback for farm animal veterinary internships is largely positive, and they may provide a useful tool with which to support newly qualified veterinary surgeons working within the farm animal veterinary sector.

KEY POINTS

- ‘Support’ was the most common motivation in newly qualified veterinary surgeons applying for farm animal veterinary internships.

- Contact with a mentor weekly or fortnightly was most likely to be considered sufficient.

- The amount of continuous professional development offered within internships varied between internships, but all amounts were considered to be sufficient.

- The majority of previous farm animal veterinary interns would recommend their internship to a recently graduated colleague.