Humans have managed livestock for millennia, and this relationship with animals has evolved over time. In the modern world, awareness of welfare implications has increased, and the role of the stockperson is thought to be key (Coleman and Hemsworth, 2014). Applying techniques to manage livestock in a positive way can potentially improve their health, welfare and productivity by reducing fear and stress (Hemsworth, 2003; Hemsworth and Coleman, 2011). Therefore, it is important that those who interact with livestock are aware of their influence on animal behaviour and how changing their attitude and behaviour may improve relationships. It is also important that appropriate training is provided to encourage this (Coleman and Hemsworth, 2014; Ceballos et al, 2018), and the effect of poor stockmanship on other parties, such as veterinarians, should also be considered. This review discusses the implications of both positive and poor relationships between stockpeople and the farm animals under their care, and suggests how poor relationships can be improved upon.

Implications of positive and negative relationships between humans and livestock

The health and welfare of livestock is paramount on farm, and the need to reduce stress and fear is included in the Animal Welfare Act 2006. The influence of human behaviour on animals should be considered because it is a key aspect of livestock farming, and a positive relationship between the stockperson and livestock can lead to improved animal health and welfare (Ivemeyer et al, 2018; Rault et al, 2020), although this is difficult to fully quantify with current evidence. Nevertheless, if this is the case, it could be positive for both the farmer and the animals and it could potentially lead to reduced costs and improved income. Conversely, it is important that there is an understanding that poor behaviour of stockpeople may elicit a negative response from animals. In general, stress in animals can lead to poor growth and production, issues with reproduction, and increased disease susceptibility (Kumar et al, 2012). These issues can be triggered by other stressors, such as heat stress or poor housing conditions, but may also potentially be caused by poor relationships between humans and livestock.

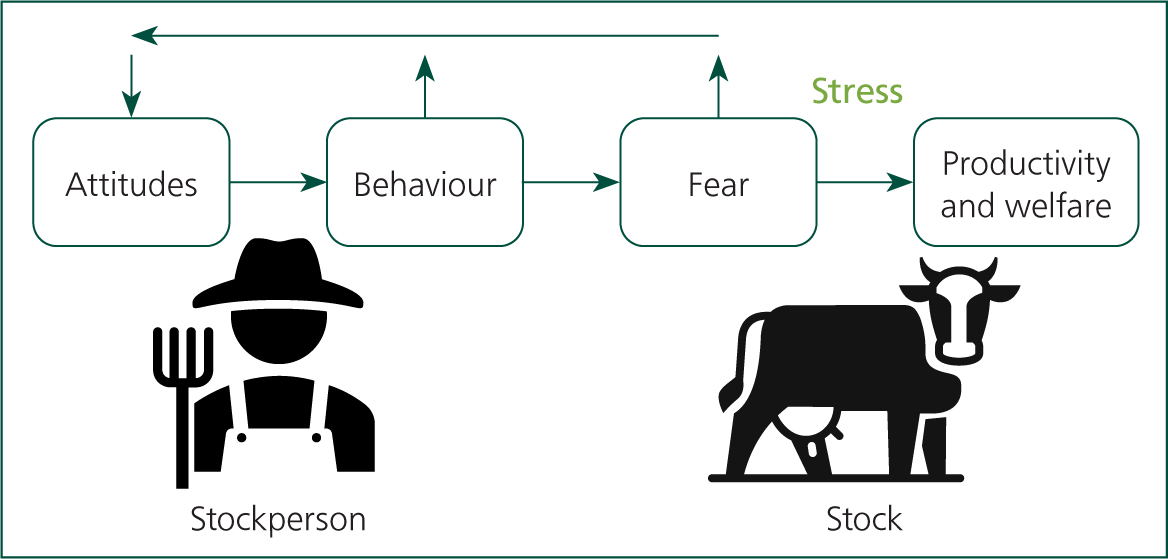

The importance of relationships between humans and livestock has been studied by many (Boivin et al, 2003; Hemsworth, 2003; Waiblinger et al, 2006; Zulkifli, 2013; Mota-Rojas et al, 2020; Rault et al, 2020), and a model by Hemsworth and Coleman (2010) (Figure 1) clearly shows how the attitudes of a stockperson can affect the behaviour of an animal. The model describes how a poor attitude can cause an animal to become fearful and stressed, which leads to poor behaviour. Subsequently, a feedback loop is formed because the stockperson treats the animal negatively as a result of frustration, which exacerbates the problem. Conversely, a positive attitude will reduce fear and stress in the animal and lead to improved outcomes in health, welfare and productivity.

Attitude of the stockperson

The attitude of handlers can be linked to the health and productivity of animals in their care. For example, according to Kielland et al (2010), a higher prevalence of carpus skin lesions was seen in the herds of dairy farmers who disagreed that animals feel pain as humans do. Empathy with farm animals is linked to the quality of interactions (Leon et al, 2020), and it can improve productivity. For instance, a study on the influence of human–animal relationships on pig farms found that farmers with the most productive pigs showed empathy for their animals (Pol et al, 2021).

A good relationship with livestock is also important for maintaining the safety of both the animal and the handler (Lindahl et al, 2016), especially when considering large animals such as cattle, which can cause injury to handlers if they are stressed (de Passillé and Rushen, 1999; Titterington et al, 2022). Moreover, negative behavioural attitudes have been associated with lower proportions of cows wanting to be touched by farmers (des Roches et al, 2016), which could lead to issues with handling and treatment. Farm animals, such as calves, can associate handlers with the colour of their clothing (de Passillé and Rushen, 1999), which could have repercussions for other handlers if the animals have been treated poorly in the past by a stockperson who had a negative attitude. However, it has also been found that cows can use other visual cues to discriminate between people, including a person's face and height (Rybarczyk et al, 2001), so it is reasonable to suggest that the colour of clothing alone may not always cause an issue.

Other factors can also affect how animals are treated on farm, including the personality, self-esteem and job satisfaction of the stockperson (Boivin et al, 2003). If the stockperson is not satisfied with their job, it is likely that they will adopt a poor attitude that could ultimately affect the welfare of animals under their care. The cyclic effect of such behaviour can reduce the job satisfaction of the stockperson further, which exacerbates the problem. Fukasawa et al (2017) found that there was a higher milk yield for dairy farmers who had higher job satisfaction and a positive attitude toward their cows, which highlights its importance in this regard (Figure 2).

Changing the attitude and behaviour of the stockperson

Positive attitudes can garner positive results, but it is not always easy to change the behaviour of people, especially if these behaviours are ingrained. The selection process is key when employing stockpeople, but attitudes can change over time, especially if the employee is not happy in their working environment. Working with production animals should be a desirable occupation (Daigle and Ridge, 2018), but staff may also need to be motivated so that they find working on farm to be a positive experience, which can also provide a good experience for the animals under their care. Adequate training to improve handling and interactions is also paramount so that a stockperson is confident that they can handle livestock appropriately and safely, which will reduce fear and stress in the animals and lead to less injuries in livestock and the handler. A hands-on approach to training is the most effective (Adams et al, 2019), and training can also improve the attitude of the stock-person. For example, Ceballos et al (2018) found that training stockpeople in good handling techniques improves attitudes and behaviours toward beef cattle. If the stockperson realises that they may be an important factor in improving animal behaviour and productivity (Breur et al, 2000; Daigle and Ridge, 2018), it could potentially lead to positive outcomes for all stakeholders, including commercial enterprises, veterinarians and the general public.

Improving human–animal relationships

Rushen et al (1999a) suggest that there are facets of stockperson behaviour that could potentially help reduce fearfulness in animals and improve relationships. These include:

- Increasing contact with animals, especially during the rearing stage (Figure 3)

- Reducing negative behaviours, such as sudden movements or talking loudly, which can startle animals

- Improving handling facilities to improve flow

- Reducing consistent bouts of aversive handling

- Trying to prevent animals learning an association between humans and fear, which can have wider implications.

Indeed, it is important that animals are not fearful in different settings, for example, or if they need to be treated by veterinarians or foot trimmers (Figure 4).

Acclimatising animals to handling early in their life can reduce fear and stress (Grandin and Shivley, 2015). Brajon et al (2015) found that piglets can associate humans with the positive experience of gentle handling following weaning. Conversely, the piglets also remembered negative experiences during the study, and rough handling caused a fear response (Brajon et al, 2015). Other researchers have also found that early human contact with piglets can reduce fear in the animals (Muns et al, 2015; de Oliveira et al, 2015), which can improve the experience for the handler, and it has also been found that piglets can develop an affinity with handlers if they experience positive interactions such as stroking and scratching (Tallet et al, 2014). Stroking has also been shown to facilitate positive emotional states in lambs (Coulon et al, 2015) (Figure 5), and reduce human avoidance in lactating dairy cattle (Schmied et al, 2008), and being brushed by a person is rated positively by calves (Westerath et al, 2014).

Research by Breuer et al (2000) shows that using harsh, loud vocalisations and speed of movement while moving dairy cows is linked with restlessness in the animals, while using quiet and soft vocalisations can have the opposite effect. In an earlier study by Waynert et al (1999), it was discovered that beef cattle were more alarmed by human shouting than by metal clanging, although both noises evoked a fear response. This evidence suggests that shouting at animals to behave in a desired manner may have negative connotations for forging good relationships with them, causing a return to the cycle of poor animal behaviour and poor stockmanship. Similarly, rough handling should be avoided because it can induce a fear response in farm animals, which has been evidenced in a study of dairy cows (Rushen et al, 1999b) where it was found that cattle can recognise and become fearful of people who have used aversive handling techniques with them. Using positive facial expressions may improve relationships between handlers and livestock. For example, goats have a preference for interacting with images of human faces with happy expressions rather than angry expressions (Nawroth et al, 2018).

Providing appropriate handling facilities so that animals can move more efficiently can be beneficial to avoid conflict between animals and handlers, and it is important that facilities are kept in good condition to avoid issues such as lameness, which can be exacerbated by impatient stockpeople pushing animals along (Burton et al, 2012). The stockperson may be perceived as an aggressor if more forceful approaches, such as using sticks, is adopted, so it has been suggested that using flags fixed to long handles to quietly move animals on is a suitable approach for livestock such as cattle (Grandin, 1999). Training staff to use behavioural monitoring tools such as Cow Signals may allow them to have a better understanding of how their behaviour is affecting livestock by focusing on changes in animal behaviour, although further research is needed to determine how this can specifically relate to human–animal relationships. Training farm animals may also be beneficial (Adams et al, 2019); Lindahl et al (2016) suggest that positive reinforcement, a technique often used in zoo animals, could be used to reduce fear in cattle. Further research is required to assess how this can work effectively on farm for different species of livestock, but it is worth considering as it could be a useful approach when treating animals.

A range of ideas to help improve relationships have been discussed and these are summarised in Table 1. Although it is acknowledged that it may not be possible to incorporate all measures because of constraints on commercial enterprises, incorporating these techniques is likely to help both farm animals and people handling and interacting with them, particularly veterinarians who may benefit from the positive relationships that stockpeople have formed with farm animals.

Table 1. Techniques that can be used to improve the relationship between stockpeople and livestock

| Technique | Reason |

|---|---|

| Form positive relationships with animals during rearing | Animals may associate people with positive experiences from an early age |

| Avoid rough handling and shouting at animals | This can cause animals to become fearful of people, which can lead to stress and unwanted behaviours |

| Use gentle physical contact such as stroking, scratching or brushing | It is likely that animals will respond positively to gentle physical contact and become easier to handle |

| Avoid making sudden movements | Sudden movements can startle animals, and can lead to stress and restlessness |

| Use positive facial expressions | Animals may react more positively to people who have happy rather than angry facial expressions |

| Improve handling facilities to improve flow | Improving flow can reduce stress in both the animals and the stockperson who is moving them |

| Train animals | Training animals may help improve their behaviour, which will lead to less frustration for the stockperson and veterinarians |

Conclusions

Evidence shows how important it is to maintain a positive relationship between the stockperson and farm animals in their care. Although further research is required, it is apparent that such relationships are mutually beneficial because they can lead to improved health and welfare for the animal and improved job satisfaction for the stockperson. Maintaining these relationships is key, as it is likely to have a positive outcome in different settings, such as during transportation, or when animals are under the care of veterinarians.

KEY POINTS

- Although further evidence is required, positive relationships between stockpeople and farm animals are likely to be important for health, welfare and productivity of livestock on commercial enterprises.

- A positive relationship between the stockperson and animals can potentially improve the job satisfaction and self-esteem of the stockperson.

- Having positive contact with farm animals during rearing is likely to benefit the relationship and interactions between people and livestock.

- Animals may associate negative experiences with people, which might lead to issues for veterinarians who need to treat them.

- It is important to train stockpeople to handle animals appropriately and improve their attitude and behaviour, which may foster positive relationships between stockpeople and livestock.