Everyone who has regular contact with sheep or cattle is an ethologist and the ability to differentiate normal and abnormal behaviour is fundamental to stockman-ship and clinical veterinary practice (Weary et al, 2009; Gougoulis et al, 2010). Some changes in behaviour can be very obvious, such as sheep hobbling on three legs or grazing on their knees when affected with conditions such as foot rot, but others are more subtle and may require closer observation and monitoring to detect abnormalities. Such ranges in responses are typical of parasitism; the intense pruritus characteristic of diseases like sheep scab is evident even to the casual observer, while a reduction in feed intake, which is a common feature of many helminth infections in cattle and sheep, can be difficult to detect in the field in free-ranging stock.

Behavioural reactions to pathogens generally have an adaptive role in facilitating compensatory responses in the host in order to counter any negative impacts of infection on form and function (Hart, 1990; Hoste, 2001); concurrently, parasites may be manipulating host behaviour for their own benefit (Simpson, 2000; Thomas et al, 2005). A classic example of this is the ability of cercariae of the lancet fluke, Dicrocoelium dendriticum, to change the behaviour of ants, which are intermediate hosts, so that they ascend the vegetation, increasing the opportunities for ingestion by grazing sheep or cattle, the final hosts (Manga-Gonzalez et al, 2001; Martin-Vega et al, 2018).

Needless to say, the subject of behaviour and parasites is extensively covered in the scientific literature and interested readers are referred to the citations provided here and standard texts to gain further background information on the many and varied associations between parasites and behaviour (Moore, 2002). This article focuses on the effects of subclinical parasitic gastroenteritis (PGE) on grazing behaviour in sheep and cattle.

Normal grazing behaviour

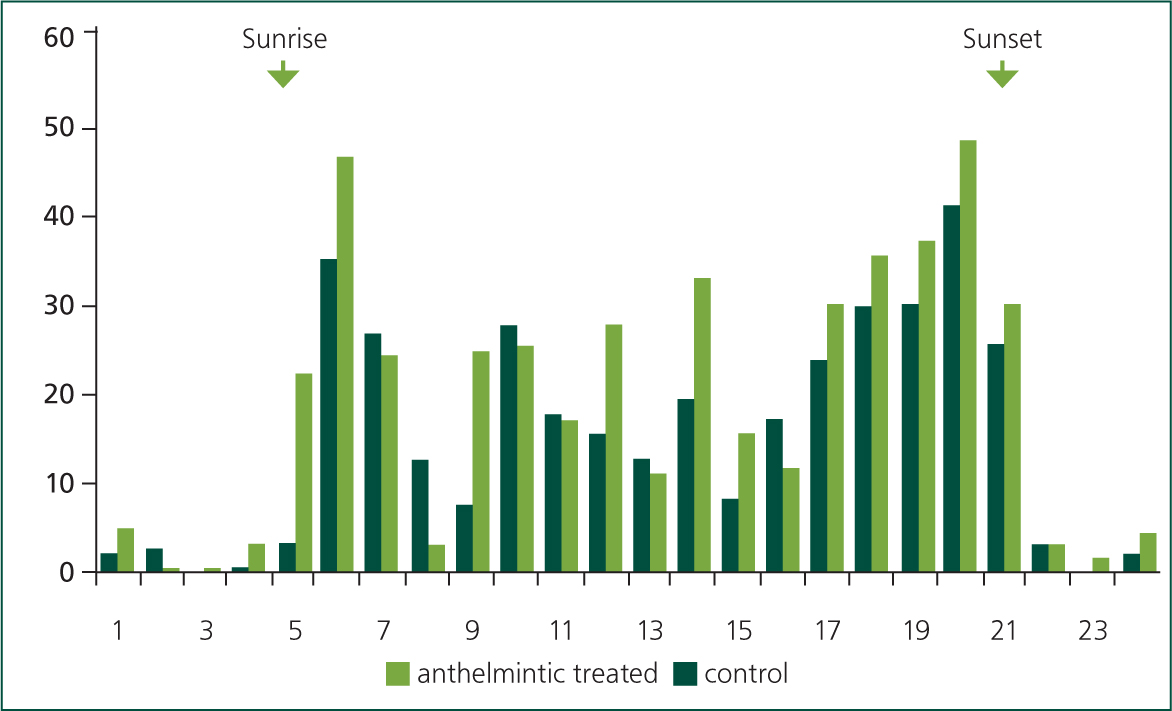

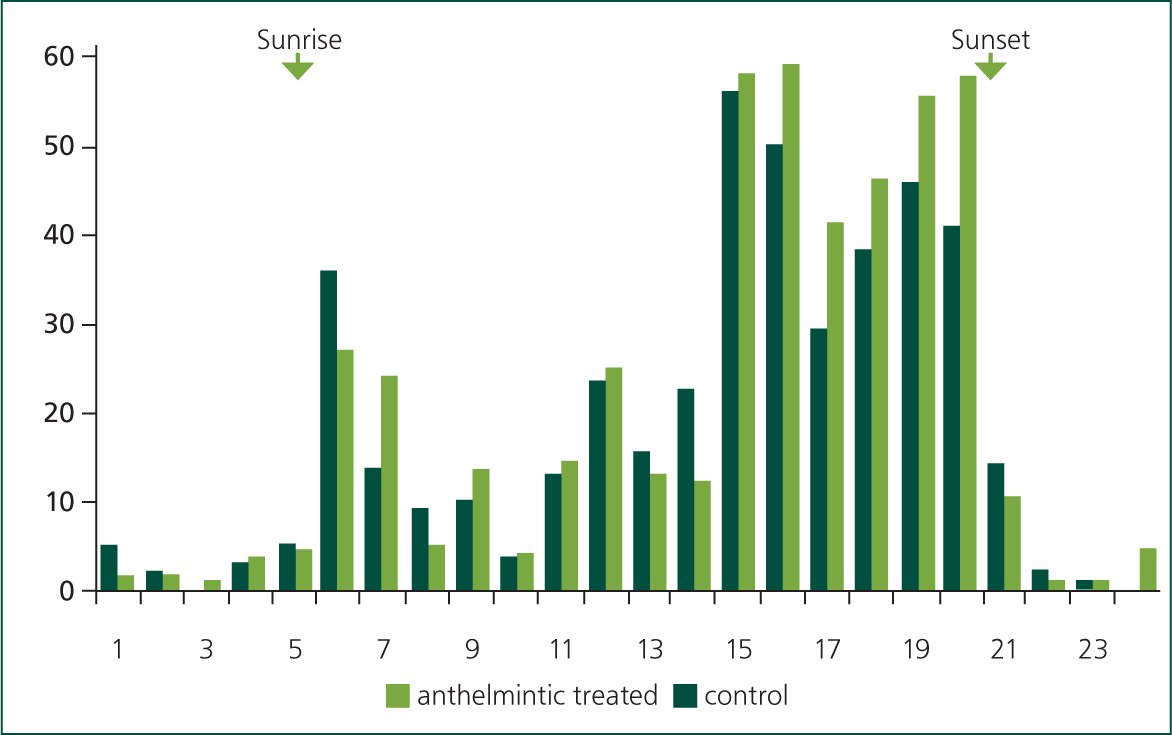

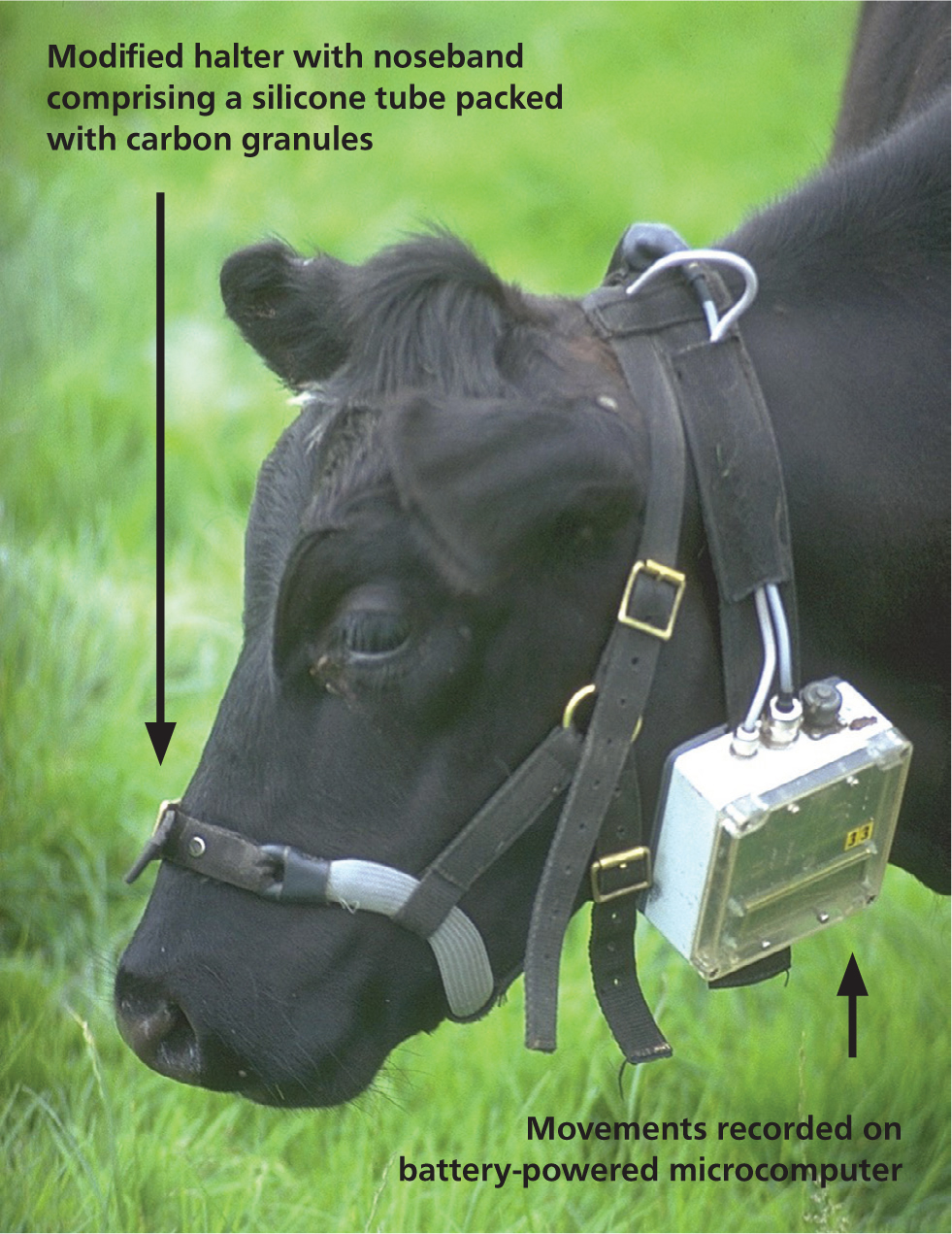

In temperate regions, cattle and sheep graze diurnally; from late spring to early autumn between 65 and 100% of grazing typically takes place during daylight hours (Hughes and Reid, 1951; Hancock, 1953; Penning et al, 1991; Krysl and Hess, 1993). Within the day there is an underlying crepuscular pattern to their grazing activity with the main bouts observed to start soon after dawn and then from late afternoon to dusk (Gregorini, 2012); interspersed amongst these main meals are additional shorter bouts of grazing, rumination, drinking, walking and resting (Kilgour, 2012) (Figure 1). These typical patterns can be moderated by management actions, most obviously when dairy cows are milked or when rotational grazing is practised (Figure 2), particularly if movement between pastures occurs at high frequency. Foraging late in the day, which can account for up to 48% of total grazing time, can be advantageous as, through photosynthetic activity during the day, the nutrient quality and density in many plants, including grass, increases in the afternoon (Delagarde et al, 2000; Orr et al, 2001; Gregorini, 2012) (Figure 3).

The amount of time spent grazing each day varies considerably, but under typical management on lowland pastures, cattle graze for 6–13 hours, with an average of around ~9 hours (Krysl and Hess, 1993); the upper limit for daily grazing time in cattle is between 12–13 hours in high producing dairy cows (Rook et al, 1994). The daily range of hours spent grazing by adult sheep is similar to that of cattle, with a mean also of ~9 hours (Arnold and Dudzinski, 1978). There are many factors that can affect the amount of time spent grazing, including:

- Animal

- Age, weight

- Breed

- Physiological state (lactating/dry)

- Health/disease

- Vegetation

- Sward height and mass

- Diversity of plant types

- Grass

- Legumes

- Forbs

- Browse

- Environment

- Altitude, slope

- Terrain

- Presence of predators or pest insects

- Weather

- (High) Temperature

- (Heavy) Rainfall

- Snow

- Season

- Daylight hours

- Time of dawn and dusk.

Herbage intake

The importance of the time spent grazing is that it is the major determinant of herbage intake, which in turn is central to the health and performance of livestock. The actual daily intake can be calculated from the equation (Gibb, 1998):

Grazing time (minutes) x Bite mass (grams of dry matter) x Bite rate (bites per minute)

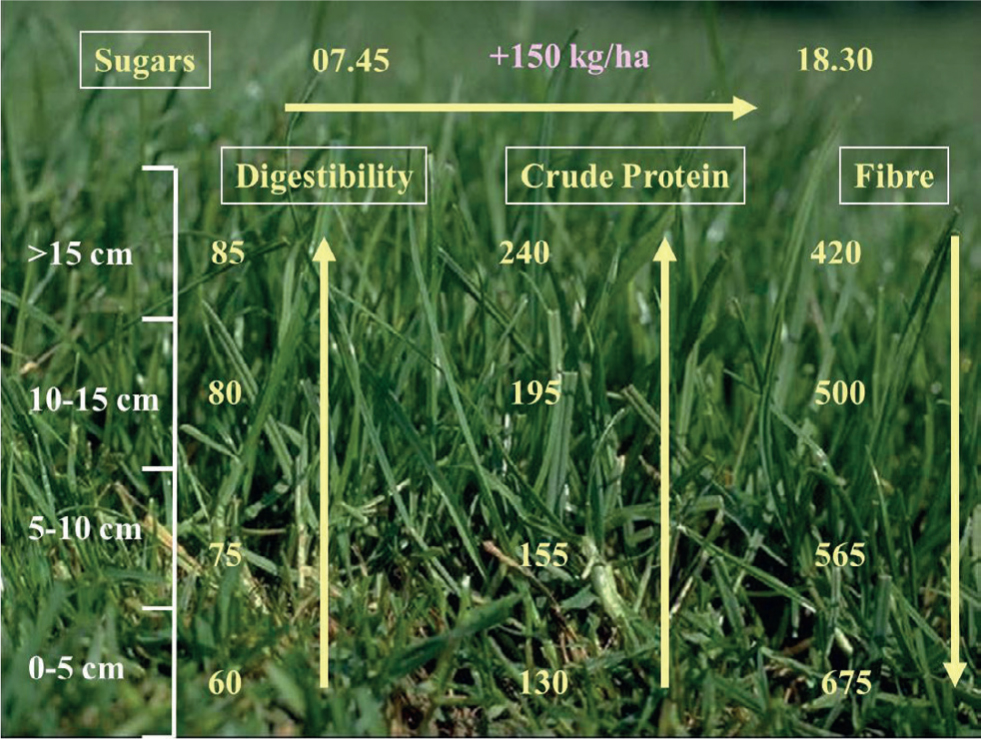

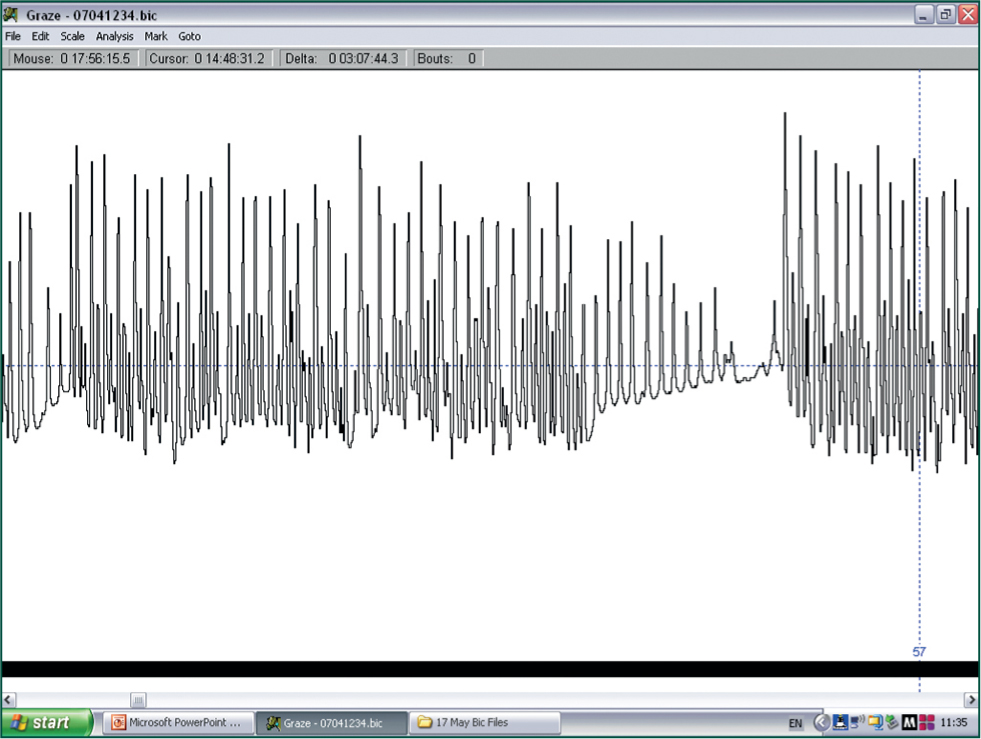

Strictly speaking, ‘eating time’ should be used in this equation as grazing includes the time animals take to move between patches of herbage during a bout of feeding (Gibb, 1998), but for simplicity ‘grazing time’ will be used, which, under uniform conditions is strongly correlated with eating time. Bite size varies according to the size of the animal and its jaw/teeth architecture, while bite rate is associated with characteristics of the herbage, such as its height and density (Forbes, 1988). Measurement of these components in free-ranging animals is difficult, but various technologies (Rutter et al, 1997; Navon et al, 2013) (Figure 4), linked with computer software (Rutter, 2000) (Figure 5), have been developed and these facilitate data collection. Direct measurement of the quantity of herbage ingested by ruminants grazing freely on pasture is virtually impossible, but there are various ways that intake and diet composition can be measured indirectly (Dove and Mayes, 1991; Lamy and Mau, 2012), and results of these analyses can be combined with behavioural observations and other tools to build a more complete picture of the daily foraging behaviour of herbivores (Ferraz de Oliveira et al, 2013).

Appetite and disease

A loss of appetite accompanied by a reduction in feed intake is characteristic of many acute and chronic diseases (Hart, 1988), providing diagnostic clues and also a mechanism to explain low weight gain, poor condition and reduced milk yield. What is less evident to an observer is the reduction in feed intake that is typical of some subclinical infections, which, by definition, cannot be detected through clinical examination alone; this is the case with subclinical PGE in both sheep and cattle. Reductions in intake are commonly reported in studies of PGE in sheep and cattle under controlled conditions when the amount of feed eaten can be measured directly. The magnitude of the reductions in intake is study and context-dependent, and can vary between 3 and 30% in sheep and 0 and 77% in cattle (Forbes, 2008), with the largest effects in the bovine seen under high challenge with Ostertagia ostertagi, and in sheep singly or co-infected with Trichostrongylus colubriformis and Teladorsagia circumcincta. In young, growing sheep and cattle, loss of appetite has been shown to account for up to 60 to 70% of the observed depression in growth rate seen in PGE (Fox, 1997).

Grazing behaviour in animals infected with gastrointestinal nematode parasites

The importance of grazing behaviour in the epidemiology and impact of helminth parasites in general and PGE in particular has been recognised for some time (Taylor, 1954; Michel, 1955), but limitations in the technology required to measure behaviours and intake under field conditions limited further quantitative investigations until the 1990s, when behavioural studies in grazing cattle and sheep were extended into investigating the effects of gastrointestinal parasitism (Forbes et al, 2000; Hutchings et al, 2001).

There are two facets of grazing behaviour in ruminants that are of interest to parasitologists and relevant to farmers, agronomists, ecologists, ethologists and veterinary clinicians:

- Reduction in appetite and intake as it relates to performance

- Faecal avoidance as it relates to herbage intake and acquisition of parasite infections.

The ingestive behaviour of grazing cattle with subclinical parasitic gastroenteritis

When calves of similar age and type are pastured under uniform conditions, those with subclinical PGE graze for ~7.2 hours a day, whereas animals that have been treated with an anthelmintic spent ~9 hours a day grazing (Forbes et al, 2000); the difference in grazing time between the controls and treated animals of ~1.75 hours is reflected in daily eating time, which is ~1.2 hours shorter in control calves (Forbes, 2008). The consequences of these differences in terms of animal performance and pasture characteristics over the 2 months from turnout are presented in Table 1. The photograph in Figure 6, shows the fence line dividing the paddocks grazed for ~2 months by control and treated calves, illustrates the differences in the sward resulting from the reduction in grazing time and herbage intake in the controls, compared with animals with negligible worm burdens. The paddock on the left of the fence that has been grazed by control animals is taller, has greater herbage mass, more stem, seed and dead material (Figure 7); all these features result from lower intakes in the infected cattle; in contrast, the sward on the right, grazed by animals with minimal worm burdens, is shorter and comprises leaf with fewer flowering stems and dead vegetation.

Table 1. Effects of subclinical parasitic gastroenteritis on animal behaviour, performance and herbage characteristics

| Infected control cattle | Treated cattle | |

|---|---|---|

| Daily grazing time (minutes) | 431 | 536 |

| Daily herbage intake (kg dry matter) | 3.9 | 4.7 |

| Average daily liveweight gain (kg) | 0.65 | 0.80 |

| Faecal egg count (eggs per gram) | 120 | <50 |

| Paddocks grazed by control animals from May to July | Paddocks grazed by treated cattle from May to July | |

| Herbage mass (kg/hectare) | 6563 | 4829 |

| Live leaf (kg/hectare) | 1929 (29%) | 1746 (36%) |

| Stem & pseudostem (kg/hectare) | 2687 (41%) | 1872 (39%) |

| Dead material (kg/hectare) | 1947 (30%) | 1211 (25%) |

Under continuous stocking, lactating dairy cows show similar responses to anthelmintic treatment; infected animals grazed for ~9.5 hours a day compared with ~10.3 hours daily in treated cows (Forbes et al, 2004). The reduced herbage intake accounted for significantly lower daily milk yields in control cows and heifers and also for lower daily live weight gain (DLWG) in the heifers. The reduction in grazing time in these studies was observed under continuous stocking on permanent pastures, but these behavioural responses can be modified by different systems. For example, when dairy cows are in a daily rotational grazing pattern, high grass intakes in the allocation following afternoon milking, which coincides with peak grazing activity, appear to mask differences in grazing times (Gibb et al, 2005). Despite the lack of evidence for effects on appetite, milk yield was still increased in anthelmintictreated cows in this study, but they did spend more time ruminating, suggesting that they may have derived more nutrients from their diet to support milk synthesis.

Diet can also affect grazing behaviour and performance and in a study in diary heifers that had access to pure swards of either perennial grass (Lolium perenne) or white clover (Trifolium repens), grazing time was ~1 hour less in infected cattle, but in this case there were no differences in DLWG between treated and control animals (Forbes et al, 2007). The DLWG on these swards was 1.2 kg/day in both groups, suggesting that nutrition was not limiting under this system and that a daily grazing time of 8 or 9 hours was sufficient to support high growth rates in young cattle, irrespective of nematode infection status.

Because grazing involves movement, as cattle walk between feeding stations and different parts of the pasture, it can be speculated that parasitised animals might have reduced foraging times that reflect their lower motivation to feed. Mobility in free-ranging stock can be measured relatively easily on commercial farms through the use of pedometers that record the number of steps taken (Ungar et al, 2018), however, a preliminary study on the value of pedometers to monitor subclinical parasitism through changes in movement patterns failed to provide robust evidence that would allow ready discrimination of animals with heavy or light worm burdens, despite differences in their DLWG (Högberg et al, 2019).

The ingestive behaviour of grazing sheep with subclinical parasitic gastroenteritis

Although the anorexic effects of PGE in sheep have been well documented in several studies in housed animals using induced single species or co-infections (Sykes and Coop, 1977; Sykes et al, 1988; Dynes et al, 1990), there have been relatively few conducted under natural conditions on pasture (Thamsborg and Agergaard, 2002) and of those that have, many are focused on an array of behaviours and interactions, rather than appetite alone (Hutchings et al, 2002a). Nonetheless, where herbage intake at pasture has been measured, both intake and grazing time have been shown to be reduced in sheep with PGE, though there is some variability in these responses both within and between trials (Hutchings et al, 2000a; Hutchings et al, 2001). Additionally, parasitism was associated with reduced motility, as measured by the number of steps taken in a day in some studies (Hutchings et al, 2000a; Hutchings et al, 2001).

Parasitism and faecal avoidance in grazing ruminants

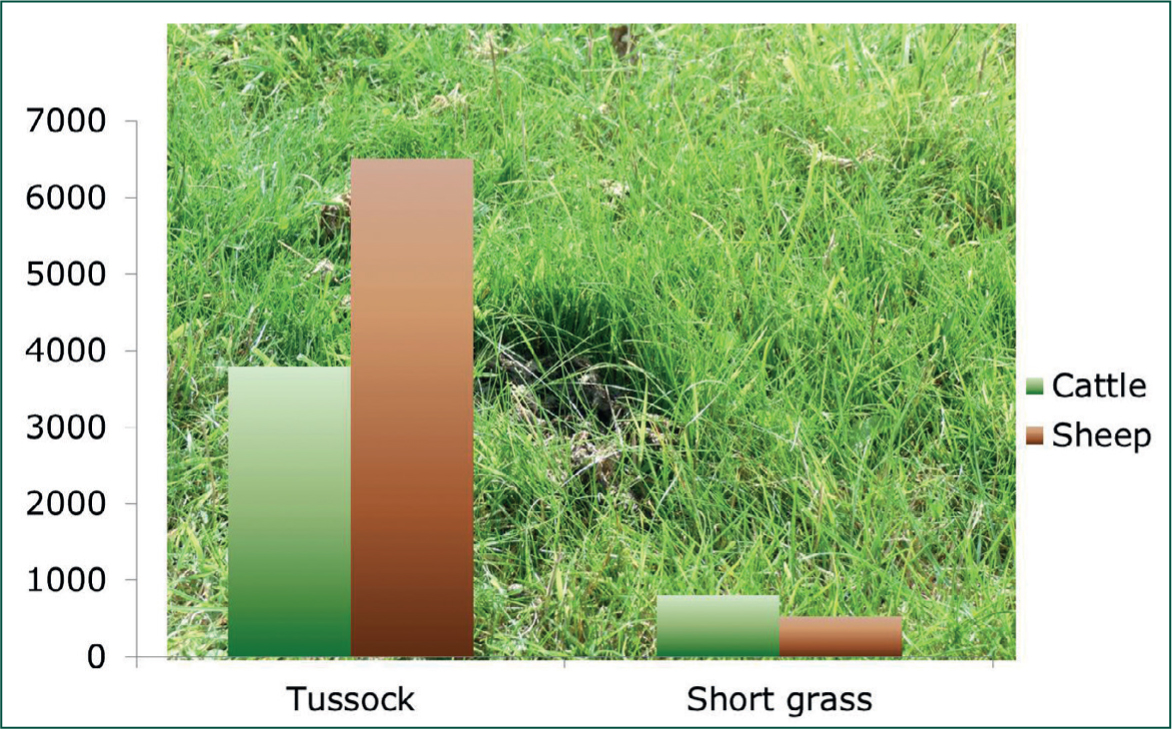

Permanent pastures grazed by sheep and cattle assume a mosaic appearance with tussocks of long, green grass interspersed among closely grazed lawns; one of the main causes of this appears to be the rejection of herbage growing near dung deposits (Figure 8). These areas of rejection are important agronomically as the utilisation of pasture is reduced, particularly in permanent pastures, where, over the grazing season, an increasing proportion of the available herbage is rejected (Castle and MacDaid, 1972; MacDiarmid and Watkin, 1972). Faecal avoidance is most marked shortly after deposition, when odour clues repel grazing animals of the same species (Dohi et al, 1991), less so amongst heterologous species (Forbes and Hodgson, 1985; Smith et al, 2009). As the grass grows strongly in the absence of grazing and with additional nutrients derived from decomposing faeces, animals use visual clues to guide their grazing decisions and continue to reject the long, green herbage near older dung deposits.

It has been speculated that the avoidance of dung and the rank herbage that grows around the sites of faecal deposits may be a response in herbivores to limit the risk of acquiring parasites, but this is very difficult to prove. Infective larvae are typically found in higher concentrations in the herbage surrounding dung than in the shorter, grazed turf (Gruner and Sauve, 1982; Raynaud and Gruner, 1982; Hutchings et al, 2002b; Hutchings et al, 2007) (Figure 9). Furthermore, there are a number of anomalies that are not consistent with either an innate or a learned response to avoid parasites or their effects:

- Sheep cannot detect infective larvae per se (Cooper et al, 2000)

- Sheep avoid grass around faeces deposited by animals free of parasites (Cooper et al, 2000)

- Few infective larvae are present on the herbage within the first week or two of deposition (Rose, 1970; O'Connor et al, 2006), when repellence to faeces is most marked

- Most infective larvae are found at the base of the vegetation, not on leaves above ~50 mm in height (Crofton, 1954; Silangwa and Todd, 1964) so the risk of ingesting larvae from tall grass is small

- Eating grass with a high nitrogen content could mitigate some of the effects of parasitism (Hutchings et al, 2000b)

- Sheep would have to associate the ingestion of herbage near dung with the negative effects of parasitism, which would not normally become evident until several weeks have elapsed.

Nonetheless, parasitism can affect grazing behaviour around dung, where it has been shown that animals with higher faecal egg counts (FEC) graze further away from faeces than those with low counts (Hutchings et al, 1998; Cooper et al, 2000; Hutchings et al, 2001; Seó et al, 2015). Interestingly, genetically resistant animals have a greater aversion to dung and its associated herbage than susceptible animals (Hutchings et al, 2007), hence, although immunological pathways are associated with parasite resistance (Aboshady et al, 2020), it is also possible that behavioural responses may be involved. Associations between helminth parasitism in cattle and olfactory system markers in their genome have been demonstrated (Twomey et al, 2019), indicating that relative susceptibility to faecally transmitted parasites may be partially mediated through olfaction.

Application and conclusion

Understanding the effects of gastrointestinal parasitism in grazing ruminants on their behaviour helps explain the impact on herbage intake and pasture utilisation on performance, epidemiology and grazing management. The development of sensor systems that can be used on commercial farms permits daily monitoring of animals, with the potential for early diagnosis of disease and poor performance at individual animal level. This in turn can be used for management interventions or targeted selective treatments to facilitate animal health and performance, while maintaining treatment efficacy (Kenyon and Jackson, 2012; Kenyon et al, 2017).

KEY POINTS

- Changes from normal behaviour are commonly seen in unhealthy animals and are fundamental to clinical diagnosis.

- Subclinical disease can also cause alterations in behaviour, but these are generally more subtle and may require regular monitoring and the use of appropriate instrumentation to be detected.

- Infections with both parasitic helminths and ectoparasites can induce behavioural changes in ruminants.

- An important aspect of subclinical parasitic gastroenteritis (PGE) in both cattle and sheep is that it results in reduced appetite and herbage intake, which in turn lead to reductions in performance, notably live weight gain and milk yield.

- Reductions in feed intake alone have been shown to be responsible for the majority of production losses in ruminants with subclinical PGE.

- Understanding some of the key mechanisms for poor performance in parasitised domestic stock can guide clinicians to appropriate mitigation strategies to counter the adverse effects of parasitism.