Recently there has been an upsurge of interest in regenerative agricultural practices amongst the farming community, the wider agricultural industry, the media and the public. The term regenerative was first used by an organic pioneer, Robert Rodale, in the USA. Not to dwell on semantics, but the (over-used) term ‘sustainable’ typically implies maintenance of the status quo and ensuring no further deterioration, whereas regenerative advocates seek to continually adapt and improve practices to reverse some of the adverse effects of ‘conventional’ agriculture. Regenerative agriculture can mean different things to different people, but its general principles typically include:

- Increasing organic matter and biodiversity in soil

- Capturing and retaining carbon in soils to mitigate high atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide and methane

- Improving the water-holding capacity of soil to enhance conditions for plant growth and reduce the impact of drought and water run-off

- Keeping livestock in a more ‘natural’ state, utilising their innate feeding and behavioural patterns on grassland and land not suitable for cropping, while limiting the use of (imported) supplementary feed

- Decreasing the use of synthetic chemical inputs, including fertiliser and biocides, in both arable and livestock farming, but without jeopardising crop or animal health and production

- Enhancing wildlife habitats and biodiversity (Figure 1).

The extent to which these aspirations are reached is currently based largely on observations, case studies, experiences and anecdotes but, given the current high level of interest, it is anticipated that outcomes of regenerative agriculture will be underpinned by more quantitative and objective research in the future. Time will tell whether regenerative farming becomes the norm or whether it is a temporary phenomenon, but there are several reasons why it is likely to play a key role in the immediate future of agriculture. Firstly, the recent increases in costs of inputs, such as diesel fuel, fertilisers and feed, are forcing farmers to reassess their farming practices and, secondly, regenerative philosophies appeal to many consumers and also to politicians, research funders and governments. DEFRA (2022) has recently introduced the Sustainable Farming Incentive, which includes elements of regenerative agriculture, such as ‘improved grassland soils’, as options to qualify to receive certain agricultural subsidies.

This article focuses on some aspects of grazing management of ruminant livestock within the regenerative ethos and its influence on the epidemiology and impact of parasites – particularly parasitic gastroenteritis (PGE) – under UK conditions. Some comments are also provided on other common parasites of stock at grass, including lungworm, liver and rumen fluke, flies and ticks. The scientific evidence basis for some of the common observations, experiences and perceptions that abound in regenerative agriculture will be explored, not to criticise, but to identify areas where more information and research would be useful.

Soil management

A core principle of regenerative agriculture in both crop production and animal husbandry is the maintenance and improvement of soil structure and function, with emphasis on its biology and organic matter, as opposed to chemical composition alone (Brown, 2018; Masters, 2019). In this it has much in common with organic farming, as espoused by its original proponents, such as Lady Eve Balfour, who established the Soil Association (Balfour, 1943).

In essence, pasture management aims to optimise the conversion of energy from the sun into carbohydrate through the process of photosynthesis in the herbage (Parsons and Chapman, 2000). This in turn feeds the plant, including its roots, which interact with soil bacteria and mycorrhizal fungi in the soil (Davis et al, 1992; Phillips, 2017), while the above ground foliage provides feed for a suite of herbivores, including domestic sheep and cattle (Waghorn and Clark, 2004). Dung and urine deposited by grazing animals are decomposed physically, chemically and biologically and enrich the soil with nitrogen and organic matter, which in turn promotes soil health (Haynes and Williams, 1993).

Regenerative grazing practices

There is a spectrum of grazing management options for lowland pastures, hill country and rangelands, but all can be fitted into a continuum between season/year long, continuous stocking to short duration (0.5–3 days) rotations using high stocking densities, interspersed with recovery/rest periods that are adequate for regeneration of herbage mass. High-intensity, short duration, long rest (HI-SD-LR) practices, described variously as holistic planned grazing (Savory and Butterfield, 2016), adaptive multi-paddock (AMP), cell, strip and mob grazing, have become synonymous with regenerative livestock farming. There are some overlaps among the various systems and management needs to be adapted according to differences in topography and seasonal changes in plant growth at the farm scale (Figure 2). Much of the research has been conducted in regions of North America and Southern Africa on large farms or ranches with greater seasonal extremes compared with temperate livestock farming conditions, typical of north-western Europe. Views on the scientific evidence for the claimed benefits of HI-SD-LR grazing management differ considerably and are hotly debated (Teague and Barnes, 2017; Hawkins et al, 2022).

Holistic planned grazing is based on the premise that some wild ungulate populations undergo long distance migrations – largely in pursuit of abundant forage of high quality, but probably also to avoid predation, parasitism and disease (Fryxell and Sinclair, 1988) – and this behaviour results in long rest periods between successive grazings of natural grasslands. While self-evidently an appealing model for livestock grazing, the analogy has clear limitations insofar as there are only a small number of species of large ungulates that undergo such long distance migrations, for example wildebeest (Connochaetes taurinus) in Africa, bison (Bison bison) and caribou (Rangifer tarandus) in North America and saiga (Saiga tatarica) in central Asia (Frank et al, 1998). Furthermore, Aurochs (Bos primigenius), the progenitors of domestic cattle (Ajmone-Marsan et al, 2010) were much more sedentary, living in marsh and forest habitats (Van Vuure, 2005), while the ancestors of domestic sheep, Mouflon (Ovis orientalis) (Hiendleder et al, 2002), can undergo altitudinal movement in the summer to high pastures in mountainous regions, but otherwise forage over smaller territories. Thus, arguably, silvopastures and transhumance may be more valid models for modern cattle and sheep husbandry, respectively, if the natural behaviour of their ancestors is considered.

Irrespective of the rationale for HI-SD-LR, there are some differences in management between it and conventional grassland husbandry, although both aim to optimise the use of pastures as sources of nutritious food for livestock. Standard advice emphasises the importance of maintaining swards in a vegetative state so that leaf area is maximised in order to capture sunlight, but also because the leaves are the most nutritious part of the plant for ruminants (Parsons and Chapman, 2000). Current recommendations are that sward heights should be kept relatively short – around 5–8 cm for sheep and 8–12 cm for cattle on lowland farms (Figure 3) – through tactical adjustments of stocking density and rest periods (Mayne et al, 2010). Generally speaking, long rest periods during the growing season result in longer swards, with herbage species being in the reproductive state with stems and seeds present. One advantage of allowing for longer intervals between successive grazings is that swards can recover and produce more biomass, which in turn helps in root regeneration (Weaver, 1950; Crider, 1955), benefiting long-term plant and soil functionality.

Guidance on target sward heights is typically based on swards of ryegrass (Lolium perenne) alone or in mixtures of grass and white clover (Trifolium repens), whereas regenerative practitioners commonly opt for more complex mixtures of grasses, herbs and forbs, which have different characteristics compared with grass/clover pastures. Thus, commonly used monitoring approaches, such as the use of sward sticks (Figure 3) and rising plate meters (Frame and Laidlaw, 2011), may not be appropriate and need adapting to complement regenerative grazing practices (Flack, 2016). In addition, some HI-SD-LR systems, for example holistic planned grazing, place emphasis on the value of ‘animal impact’ (Figure 4), which, through the action of trampling hooves, results in uneaten vegetation and dung being incorporated into the upper soil layers, helping to restore organic matter (Savory and Butterfield, 2016).

Interactions between pasture and parasites

The principal species of gastrointestinal nematode parasites of cattle and sheep have direct life-cycles. That is to say there are no intermediate hosts; transmission takes place when infective larvae (IL3) are ingested during grazing and these larvae are derived from eggs deposited in the animals' dung. PGE can therefore be described as an auto-infection insofar as the sources of pasture contamination with parasites are the herds and flocks themselves. This then underpins one of the cornerstones of PGE control and that is to limit pasture contamination with worm eggs, thus reducing potential populations of infective larvae, and limiting exposure of livestock to infection (Morley and Donald, 1980). Deposition of worm eggs on pastures by grazing stock can be much reduced through the strategic use of anthelmintics, which by definition usually means treating groups of (infected) animals within 3 weeks of movement onto a pasture before they can contaminate the fields via their dung (Forbes, 2021). There is abundant evidence for the effectiveness of these strategies in young cattle (Shaw et al, 1998a; 1998b), weaned lambs (Brunsdon, 1966) and to some extent in twin-bearing periparturient ewes (Taylor et al, 1997), but this type of approach does not sit comfortably with the principles of regenerative agriculture or other organisations or individuals that seek to limit the use of anthelmintics.

There are a number of practices, individually and collectively, that can modify the epidemiology and impact of PGE in ways that do not rely on anthelmintics (Stear et al, 2007), these include:

- Grazing management (Forbes, 2017b; 2017c)

- Creating and using low-risk pastures, including new leys

- Mid-season move of stock to low-risk paddocks, eg silage/hay aftermaths

- Mixed age and ‘leader–follower’ systems

- Sequential or co-grazing mixed livestock species

- Increasing sward diversity: eg herbal leys (Lisonbee et al, 2009; Jordon et al, 2022)

- Optimisation of nutrient supply and quality throughout the year (Coop and Kyriazakis, 1999; Mayne et al, 2010; Younie, 2012)

- Biological control, eg nematophagous fungi (Healey et al, 2018)

- Utilising breeds best adapted to regenerative systems (Provenza, 2008)

- Breeding ruminants for increased resistance or resilience to gastrointestinal nematodes (McManus et al, 2014).

The wide range of principles and practices of grazing management and the fact that they can change both within and between grazing seasons means that is virtually impossible to study all the effects on parasitism, but a good understanding of the factors that affect the epidemiology of PGE (Brunsdon, 1980), particularly the ecology of the free-living stages on pasture, can at least provide a basis for reasonable assumptions and educated extrapolations.

Larval ecology of gastrointestinal nematodes of cattle and sheep

The three key elements of larval ecology are:

- Development of infective larvae from worm eggs within faecal deposits:

- Providing that the faeces maintain adequate moisture levels, hatching of eggs and the subsequent development of larvae is temperature-dependent

- Temperate gastrointestinal nematode species typically develop optimally over temperature ranges of 20–25°C, when IL3 can appear in less than a week, with the majority mature within 2 weeks of deposition (Forbes, 2021; Gyeltshen et al, 2022)

- Generally, there is little/very slow development below 10°C and at the other end of the scale, temperatures of 30–35°C and above can be lethal to several species, particularly if accompanied by desiccation of the dung.

- Translocation of IL3 from dung on to the grazing horizon in the surrounding herbage

- Infective larvae need a film of moisture to move actively, but the extent of their migration is limited to a few centimetres horizontally or vertically from the faeces (Rose, 1961; Silangwa and Todd, 1964; Williams and Bilkovich, 1973; Leathwick et al, 2011)

- Longer distance movement of IL3 to herbage distant from bovine dung pats is greatly facilitated by raindrops, which physically splash the larvae out of the faeces for distances of up to a metre (GrØnvold, 1987)

- The converse is also true, there is very little movement of IL3 away from dung when the weather is dry, say during a summer drought (Figure 5), but when rainfall resumes, there can be a massive release of IL3 that have accumulated in the dung in the interim (Rose, 1962).

- Survival of IL3 in herbage and soil

- IL3 do not feed and rely on stored energy sources to fuel their metabolism and movement, which results in a progressive decline in these resources until the larvae die, if they have not been ingested by a suitable host

- As invertebrates, IL3 metabolism is temperature-dependent, so seasonal changes in environmental conditions can affect survival, being prolonged in cool conditions and accelerated in warm weather (Rose, 1963), thus larvae survive better over a cold winter (Figure 6) than a mild one (Wang et al, 2020)

- How long IL3 survive in a pasture depends on factors additional to the weather, including the composition of the herbage (Moss and Vlassoff, 1993; Niezen et al, 1998; Marley et al, 2003), the microclimate in the vegetation, litter and soil layers (Moss and Bray, 2006), and the populations of invertebrate predators and nematophagous fungi (GrØnvold, 1987)

- Soil can be a reservoir for infective nematode larvae (Al Saqur et al, 1982), although little is known of any interactions with other soil fauna or soil composition.

Most of these data have been generated under controlled conditions in the laboratory or the field, but few under regenerative regimes. Differences in the microclimate, height, morphology and profile of complex swards (Figure 7) compared with botanically simpler vegetation may well affect the rate of development of infective larvae, their translocation from dung to herbage – whether by active movement or passive transfer – and their survival.

Rest periods in rotational grazing and longevity of infective nematode larvae

Subject to environmental conditions, infective larvae of the common gastrointestinal nematodes of cattle – Ostertagia ostertagi and Cooperia oncophora – and sheep – Teladorsagia circumcincta and Trichostrongylus species can readily survive for several months during the grazing season and over the following winter, although larval populations on pasture typically decline to reach low levels by mid-summer the following year. However, residual numbers of larvae on pasture in the spring are sufficient to initiate infection when animals are turned onto fields that have previously been grazed (Rose, 1961; Rose, 1965) and can occasionally cause PGE (and lungworm) even later in the season (Armour et al, 1980). Larvae have been shown to survive for 2 years or maybe more in the soil, so it should not be assumed that permanent pastures are completely free of infection, even if ungrazed for several years.

Assuming that some animals are infected when they enter a rotational grazing programme, then they can pick up any surviving infective larvae and simultaneously recontaminate the pasture with eggs from their current infections. If animals are not infected when they enter a paddock, providing they remain for ~2 weeks or less, they should not add to the contamination of the pasture with nematode eggs, because the minimum pre-patent period for the common gastrointestinal nematode species is 2–3 weeks (Forbes, 2021). If animals return to the same paddock during the same grazing season, they will be re-exposed to any residual infection present plus larvae that have developed from eggs deposited during the previous grazing round (Kunkel et al, 1983). Even if the rest period between successive grazings is 1 year, there may still be infective larvae present on the pasture.

Again, much of the currently available data cited above have largely been generated in conventional conditions and it is possible that some features of regenerative agriculture grazing, such as plant diversity, taller swards and trampling could lead to different outcomes. However, with the possible exception of systems with long resting periods (>1 year), in temperate regions, rotational grazing alone is unlikely to provide consistent, effective control of PGE (Gibson and Everett, 1968; Michel, 1969a; Eysker et al, 1993).

Monitoring PGE during the grazing season

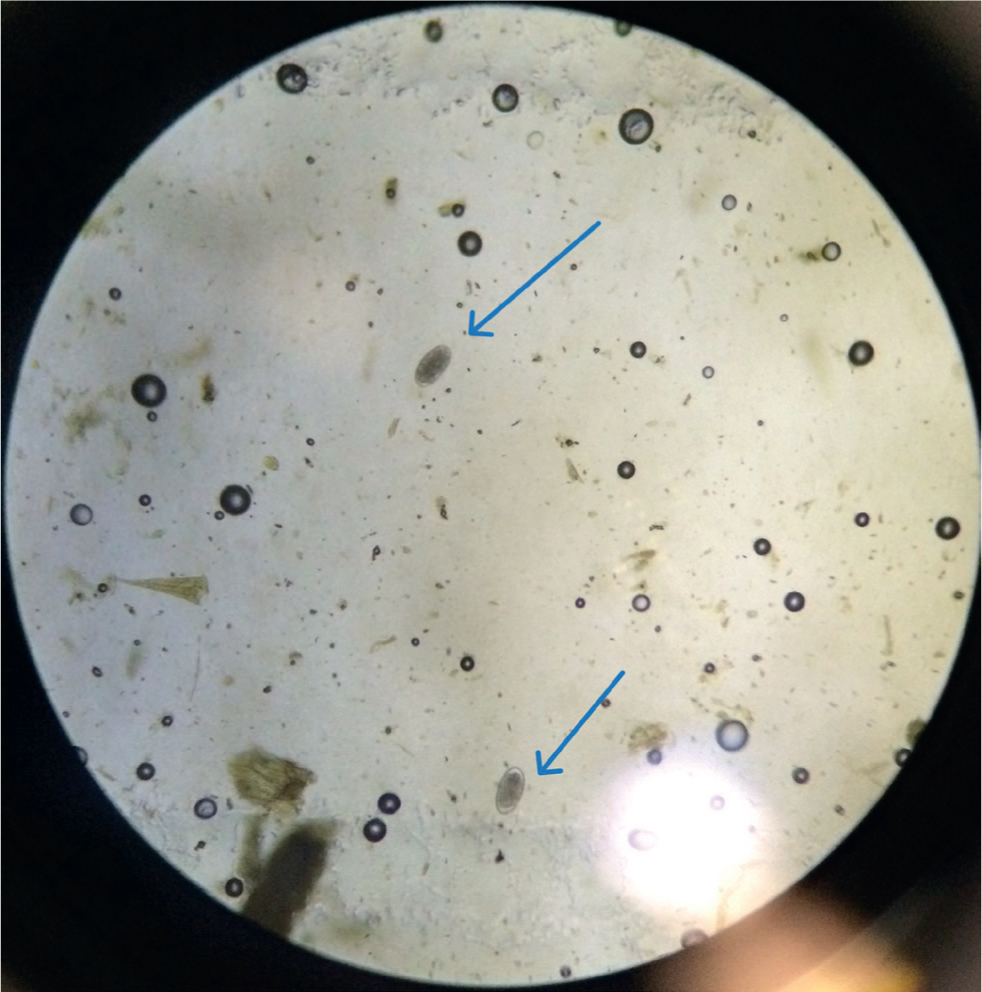

Included in the ethos of regenerative agriculture is a reduction in the use of chemical inputs, so strategic and routine use of anthelmintics in groups of susceptible stock is discouraged. Hence animals need to be monitored in case PGE interferes with performance and/or causes clinical disease, particularly in young sheep and cattle in their first and second grazing seasons. Sampling faeces for the presence and visualisation of parasite eggs (Figure 8) is unquestionably a brilliant way for engaging farmers and stock owners in parasitology; faecal egg counts (FEC) can be also used quantitatively in various ways, including assessing anthelmintic efficacy, studying the epidemiology and seasonal patterns of PGE and in predicting the risk and impact of PGE (Sabatini et al, 2023). However, in temperate regions where Haemonchus species are not dominant, nematode FECs alone do not accurately reflect either parasite populations (burdens), nor impacts on the host. This generalisation applies particularly to cattle, but also to some extent to sheep (Anderson et al, 1965; Michel, 1969b; Greer and Sykes, 2012; Sargison, 2013; Forbes, 2017a). There are some general guidelines (with appropriate caveats) for the interpretation of FECs in lambs (Sabatini et al, 2023), but several organisations, advisory bodies and individuals extend this approach to cattle FECs, in which there is no scientific evidence base to support any of the various notional eggs per gram (EPG) ‘thresholds’ (for anthelmintic treatment). The limitations of FECs as quantitative measures of parasitism in general and in cattle in particular have been regularly highlighted in the scientific literature for over 80 years (Taylor, 1935; Michel, 1968; Eysker and Ploeger, 2000; Sabatini et al, 2023).

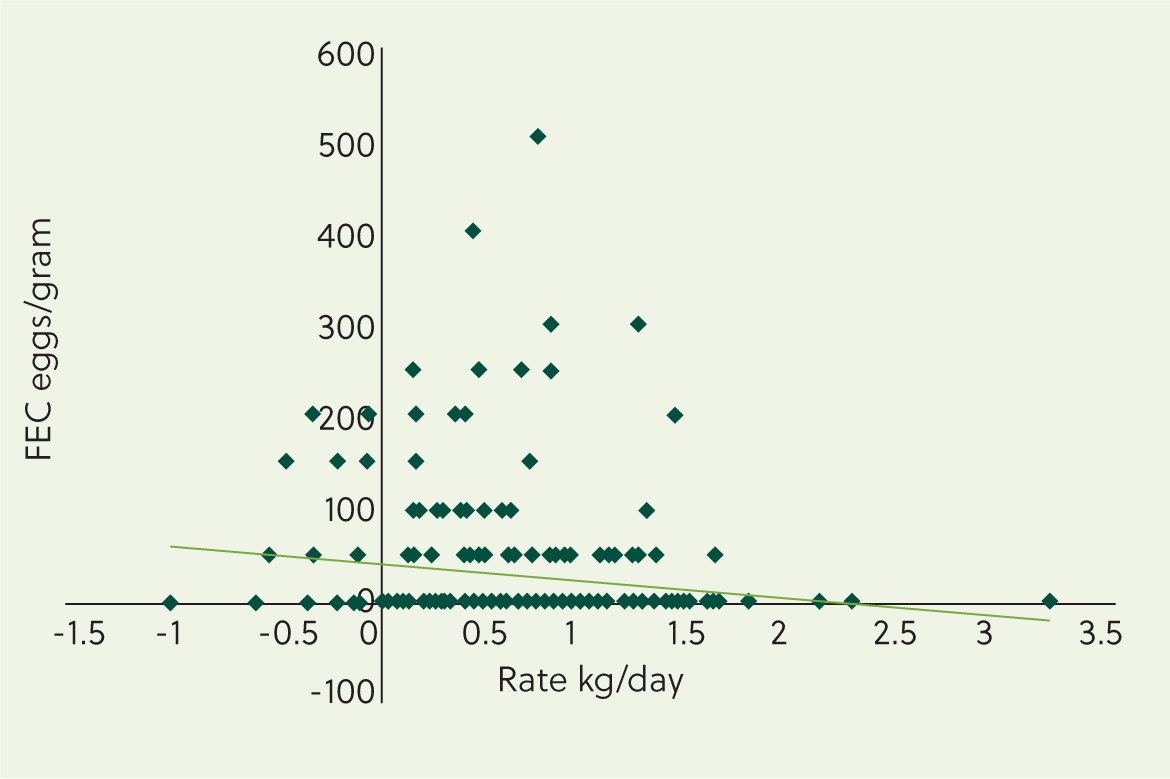

By way of illustration, data from young grazing cattle showed that a ratio between EPG and worm burdens of between 1 and 1788 gastrointestinal nematodes (Brunsdon, 1971). Thus a ‘low’ count of 100 EPG could represent a population of gastrointestinal nematodes between 100 and 178 800; the former would have no measurable harmful effect on the host, whereas the latter could cause clinical PGE (Anderson et al, 1965; Brunsdon, 1968). Similarly, data from a study on targeted selective treatment found no statistically significant, nor diagnostically useful, association between daily live weight gain and FEC in young cattle (Jackson et al, 2017) and the graph shown in Figure 9 illustrates this. Most strikingly is the baseline, representing <50 EPG (the sensitivity of the McMaster technique used, ie no eggs were seen in these samples), in which the growth rates (ignoring some outliers) varied between around minus 0.5 to plus 1.5 kg/day. The bulk of values lay between 0 and 1.5 kg/day, with approximately 50% of animals growing at less than 0.7 kg/day, a minimum target value for productive young cattle (Wathes et al, 2014). Interpreting cattle FECs in temperate regions as quantitative estimates of worm burdens and/or adverse effects on performance (low growth rates) of gastrointestinal nematodes in the host, and hence indicators for treatment, are thus disingenuous and lack scientific validity and credibility.

There are a number of other diagnostic tests for nematodes and other helminth parasites (Ellis et al, 2011): some are based on individual blood samples, others on individual or bulk milk samples. While such tests are commonly used in research, on commercial farms an assessment is needed to determine how much extra, useful information can be gleaned and whether they are cost-effective or not. In young ruminants in temperate regions, the best tool for monitoring the impact of PGE currently is daily live weight gain, which, providing nutrition is adequate and there are no other barriers to growth, is a useful surrogate for PGE in both lambs and calves and most targeted selective treatment approaches in youngstock are based around this parameter (Kenyon et al, 2009; Charlier et al, 2014; Busin et al, 2014; Jackson et al, 2017). The superiority of daily live weight gain compared with FECs as a marker for targeted selective treatment has also been confirmed in models (Berk et al, 2016; Laurenson et al, 2016) in both young sheep and cattle.

Although weigh bands can provide valid estimates of body weight in cattle (Jackson, 2012), their on-farm use can be difficult; adequate restraint and ideally two persons are required to use them effectively and safely. Weigh scales are a much better option for both lambs and cattle, but many livestock units, particularly cattle farms, do not possess them. Even experienced farmers and largeanimal veterinarians are poor at estimating the weight of stock by eye (Besier and Hopkins, 1988; van Dijk et al, 2015), so if farmers are to monitor their stock efficiently, they would be well advised to save money on FECs and instead invest in a good handling and weighing system (Figure 10) if they are to foster good animal husbandry, meaningful monitoring and accurate dosing if treatments are needed (Forbes, 2021). Further developments in precision farming, such as automated weighing at pasture (Segerkvist et al, 2020), monitoring grazing behaviour and activity patterns (HÖgberg et al, 2019), could further facilitate and enhance monitoring grazing livestock for PGE (Aquilani et al, 2022).

Other parasite infections and co-infections in regenerative systems

The focus of the previous sections has been gastrointestinal nematodes as they are ubiquitous in pasture-based livestock farming, but of course grazing livestock can be exposed to the risk of other parasites, for example, lungworms (Dictyocaulus spp. in cattle and sheep) tapeworms (Moniezia spp., though these generally lack major impact), liver (Fasciola hepatica) and rumen fluke (Calicophoron daubneyi). In addition, flies and ticks can infest animals at pasture and these can be responsible for direct damage to the host, but also are vectors of several important diseases (Forbes, 2021). Lungworm could pose a real threat on stock farms, particularly where anthelmintic use is minimal, but there is a vaccine that can be used in cattle, although whether rotational systems are optimal for the required concurrent natural exposure to boost immunity has not been established.

The risks posed by fluke are more easily established as the distribution of infection is closely allied to the location of suitable (wet) habitats (Wright and Swire, 1984; Rondelaud et al, 2011) favoured by the intermediate host of both rumen and liver fluke, the mud snail, Galba truncatula. If such habitats are present on regenerative farms and within grazing rotations, then the use of flukicides may be required as there currently are few, if any, alternatives to control. The mantra for fluke control should be ‘test don't guess’ as exposure to infection is not always predictable from year to year on farms. Faecal sampling of older animals throughout the year will give some indication of patent infection and potential pasture contamination. Blood sampling for serological monitoring of sentinel animals (first grazing season lambs or calves) can provide useful information in the autumn as to the presence and timing of fluke exposure and allow more precise information to guide the use of flukicides (Sabatini et al, 2023).

Tick habitats can also be identified at the level of the farm and its surroundings, but the extent to which regenerative grazing might affect these parasites in the UK is unknown, although there is some evidence for benefits in savannah regions of Africa (Rapiya et al, 2019). Similarly, little is yet known of possible effects of rotational grazing on pest fly populations, some species of which breed in dung, but the high stocking densities and close herding typical of mob-grazing systems could influence host responses (Dougherty et al, 1993) and fly biology. Fly strike, caused by the larvae of Lucilia sericata, is a very unpleasant disease of sheep and the incidence of breech strike is closely associated with faecal staining and contamination (dags) around the tail and rump, consequent to diarrhoea: commonly caused by PGE in lambs. Such interactions between PGE and other parasite infections, which typically increase the overall negative effects on the host, need to be included in a farm parasite audit and in considering control options (Forbes, 2021).

Conclusions

Regenerative agriculture is currently the subject of great interest both among farmers and within the wider community and this has resulted in a burgeoning of relevant (scientific) literature and also web-based material. However, much of the research, particularly on holistic planned grazing-type systems has been conducted in range and savannah regions, that typically involve much larger units than are typical of those in the UK, and where they experience more extreme seasonal weather patterns characterised byseasonal droughts or freezing conditions. Hence, caution should be exercised when extrapolating findings to temperate regions; however, most farmers who practise regenerative agriculture in the UK are satisfied at many different levels of its benefits (Figure 11) and enthusiastically endorse its approaches. Such farmers also report that problems with parasites diminish with the adoption of regenerative grazing practices and there is some basis for these claims insofar as they reflect aspects of parasite biology and ecology. Current and future research on regenerative grazing and its impact on parasitism will hopefully provide further insight into these complex but fascinating interactions.

KEY POINTS

- Regenerative agriculture combines soil, herbage and animal management with the aim of restoring and improving the ecology of pasture.

- Botanically diverse swards and silvopasture can contribute positively to these aims.

- Rotational grazing is associated with regenerative practices with short-stay, long rest periods featuring strongly.

- Collectively, these approaches can reduce the impact of parasitism, but there is a need to generate more field data to verify and quantify these effects.

- Monitoring animal performance in conjunction with valid, quantitative parasite diagnostics can inform the veterinarian and farmer as to the efficacy, or otherwise, of their management in fostering high levels of animal welfare and supporting good productivity.