There are many different models that practices use for charging farm clients for their professional services (Table 1). Ideally, the model needs to be equitable for veterinary surgeon, client and animal. Different structures can influence how a practice's services are used. It can also influence which services are successful.

Table 1. Fee charging models for farm practice

| Model | Example | Advantages | Disadvantages | Additional notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed fees for individual tasks | Every task is itemised, such as:Cow Caesarean, £200Rectal examination, £5.00Examination fee, £25Dehorn yearling, £15 etc |

|

|

This is probably the most traditional model. Works better for traditional style farm veterinary visits: an individual sick animal or a few rectal examinations and a lame cow, for exampleThe model is used extensively in companion animal practice and so may be favoured by mixed practices as it is within the practice cultureIt suits traditional farm veterinary tasks, like those listed in the examples, but is less useful for health planning or advisory work |

| Hourly rates | Typically £100–150 per hour. Some practices have different hourly rates depending on veterinary seniority/experienceSometimes higher hourly rate for out-of-hours workSome practices charge differentially depending on time of day, or if on-farm or off-farm work |

|

|

A large variable, perhaps even more so than the hourly rate, is the accuracy of time actually charged. There can be a tendency for veterinary surgeons to chronically under-chargeSome practices have automated charges based on mobile technology (time spent on farm using vehicle GPS trackers)It is very common for practices to charge at least the routine (pre-arranged) work by the hour, if not everything. For dairy farms, this is predominantly fertility visits |

| Visit charges | There are probably as many ways to charge for visits as there are veterinary practices! Typical examples include a fixed fee based on distance from the main practice, or based on the time of day or night, or bothMany practices will have different visit charges depending on whether the visit was pre-arranged (routine fertility visit, for example) or not |

|

|

Motoring costs are considerable for farm animal practices. However, the larger element of cost is actually time wasted on journeys, which is unproductive for everyoneProviding an emergency service, which is an obligation for farm practices, is incredibly expensive. While farmer surveys suggest they value the emergency service that veterinary surgeons provide, it is arguable that they would not be prepared to pay the true cost. An insurance scheme would be a logical step, if veterinary surgeons were not already obliged to provide the service in any event |

| Contracts for professional service packages | Very variable in scope and how practices are adopting this model. Might include, for example, delivery of a mastitis investigation and plan, for £750Alternatively, a premium health planning service with quarterly business meetings and data review, paid by a monthly subscriptionAlternatively, may be a more over-arching contract, for example 0.45 pence per litre (ppl), charged at a fixed monthly fee, to include all vet fees except out of hours visits (and not medicines) |

|

|

If used at all, this model is still experimental in many practicesIn some ways, it can be an extension of the set-item fee model, except with larger packages of work, with the same advantages and disadvantagesA monthly emergency call-out subscription could be used to off-set the cost of individual out-of-hours visits |

| Professional services plus medicinal product wrap | Includes a combination of medicines and service, such as a calf health plan which might include measuring, benchmarking, debudding and pneumonia vaccination at £20 per calfInfectious diseases plan: herd disease monitoring; disease control planning; vaccinations; assistance with vaccine administration at £20 per head per yearCould be as simple as a dry-cow package for seasonal calving herds, which is a service delivered by the veterinary practice of drying off the cows. This is widely practiced in New Zealand |

|

|

This is analogous, perhaps, to companion animal practices which offer pet health plans which include all parasite control and annual vaccinations and 6-monthly check-ups for a fixed monthly feeIt is a highly evolved service package which departs from splitting the professional fees and medicine sales. It recognises that supplying medicines by themselves is not the same as delivering a vaccination programme, for example, which requires considerable skill and organisational excellence if it is to be successful |

A recent Nuffield Farming Scholarship report (Remnant, 2020) highlighted how common it is for cattle practices worldwide to find it challenging to incorporate advisory or preventative work into a successful business model. As the report notes, it is not unusual for farm veterinary surgeons to make their living from the 5% of cows that get sick rather than the 95% that they prevent getting sick.

This article takes a look at fee charging in farm practice. It is an opinion piece. There is not a one-fit solution that will suit all practices and I certainly do not have all the answers. However, my own feeling is that the time is ripe for a more widespread progression towards a subscription-style charging model, at least for advisory work, and possibly for out-of-hours emergency work.

A (recent) history lesson

During my 25-year professional career, there has always been a certain tension around how farm veterinary surgeons earn their keep. Traditionally, one would say, medicine sales have supported income from fees. In the late 1990s, the government of the day ordered a Competition Commission enquiry into veterinary surgeons' charges (Competition Commission Report, 2003). Almost simultaneously, the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food ordered its own review of dispensing veterinary medicines by a team lead by Professor Sir John Marsh (Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheris amd Food, 2001). The recommendations of both reports certainly focused pressure to change the veterinary business model, to derive a greater proportion of income from professional fees and less from medicine sales. A great part of the political drive was in order to reduce medicine prices for hard-pressed livestock farmers who had recently lived through the devastation of the 2001 foot and mouth catastrophe, and were still in the throes of the bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) crisis.

Whether because of this political pressure, or other changes to the demographics of farms and veterinary practices, the turn of the century saw a new phenomenon of farm-only veterinary practices. In addition, there was an acceleration of mixed practices specialising into farm, companion and equine divisions (Lowe, 2009). Some mixed practices shed their farm work to concentrate on companion animals. Many of the new farm practices did indeed significantly reduce the price for medicines and increase their fee rate.

The landscape continues to evolve and today the majority of farm veterinary work is done by dedicated farm practices or dedicated farm teams within larger mixed-species practices. There has been increased competition on medicine prices, and farmers can undoubtedly buy medicines relatively more easily and cheaply than they could 20 years ago. Internet pharmacies have made it more possible for farmers to benchmark medicines prices, including with overseas sources, and this has levelled the playing field for them to some extent.

The status quo

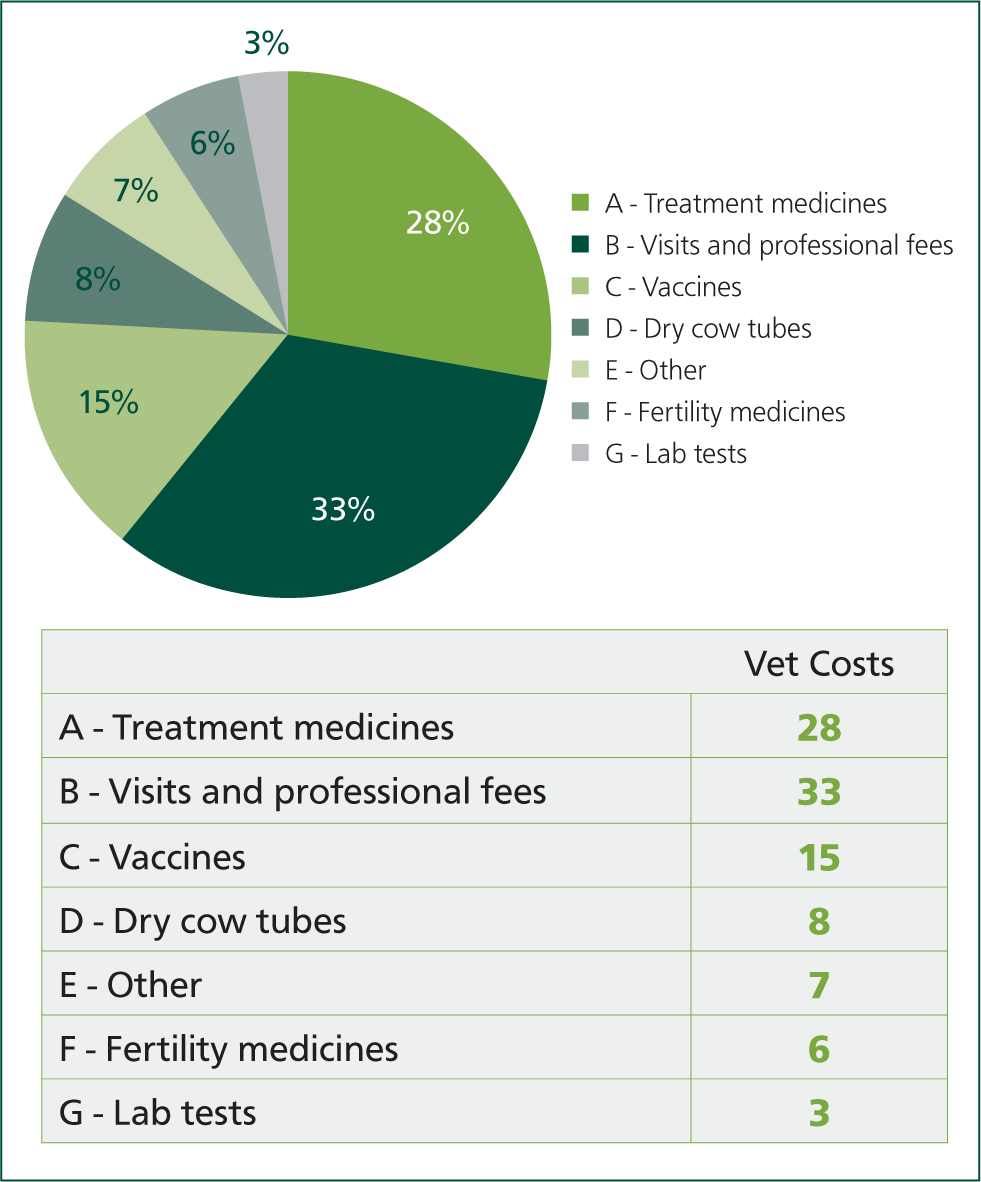

To what extent have these changes helped farm veterinary practices wean themselves from their reliance on medicine sales? I would contend that the dependency remains strong. The dairy sector is the one I am most familiar with, and I will use this to illustrate the point. A typical dairy farm pays around 0.7–1.0 pence per litre, or £60–90 per cow per year, on their veterinary bill (excluding VAT). For a mid-yielding 200 cow herd with some youngstock, this amounts to approximately £15 000 per year, or £1250 per month. Typically, around 66% of this is for medicines and 33% for professional fees (Figure 1). Of the medicines, a typical overall margin is around 35%. Therefore, the practice income looks like this:

- Professional fees — £415/month

- Medicines — £835/month

- Margin on medicines — £300/month.

Give or take, the veterinary practice in this example makes about 60% of its net income out of fees and 40% out of the margin on drug sales. For the sakes of simplicity, government contract TB testing and other extraneous work has been excluded.

The medicines sales literally walk out of the door, with relatively little effort, while the professional fees are usually hard won, involving expensive travel to the farm, expensive veterinary time and very often considerable blood, sweat and tears; sometimes at unsociable hours.

A cynic might say that farmers are reasonably happy because they have what they always asked for: cheap medicines which are readily available and affordable veterinary fees which do not prohibit the treatment of individual animals, including an affordable emergency service should they need it. Farm veterinary practices can remain profitable because farms have grown in size so medicine sales are easier to service. If you like, fewer but larger farms with greater purchasing habits have facilitated a stock-‘em-high, sell-‘em-cheap approach to medicine sales, at least relative to the olden days. The margin on individual medicines may be lower, but the volume has increased and the cost of dispensing has reduced so the profit remains significant.

Why change?

If the current model is suiting farmers and veterinary practices, then why change? From an animal health perspective, cheaper medicines are no bad thing when we are considering preventative medicines such as vaccines. From a cost perspective, there really should not be much of an economic barrier for farmers using the common cattle vaccines, assuming they are indicated. However, the concept of large volumes of cheap and readily available medicines does not look so honourable when we consider antibiotics. And in reality, most of medicine sales (on a cost-to-farmer basis) are still treatment medicines rather than preventatives (Figure 1).

The accusatory finger might still linger over farm practices that they have little incentive to prevent disease because they derive a lot of income from selling treatment medicines, in particular antibiotics. These treatment medicines usually have a higher profit margin compared with preventatives; this compounds the argument. This criticism is certainly valid, however ethical individual veterinary surgeons are (and I believe most are). I feel we should hear this criticism and concern, and strive to evolve our fee models and prescribing practices to address it.

The pressure for change is coming not only from progressive farmers, but from an increasingly integrated food supply chain. For the dairy sector, milk buyers and supermarkets are keen to reduce antibiotics used on dairy farms and I expect we will continue to see increased constraints on veterinary surgeons' prescribing habits in the future.

Meanwhile, the steady downwards pressure on medicines prices will continue. Increasingly, the squeeze will be on veterinary practices that can no longer afford to provide the subsidised emergency services which farmers have hitherto benefitted from (Remnant, 2020).

Finally, I detect a palpable frustration among more progressive, usually younger dairy farmers who are looking for a very different approach from their veterinary surgeons compared with the usual task-based input which is characterised by routine fertility visits. These farmers are already commonly benefitting from advisory input from other professionals, including dairy consultancy businesses. They value and want strategic, efficiently delivered professional advisory input. Importantly, they want this from a veterinary surgeon who is not in a rush, who is not working on the fly, who is prepared to work collaboratively, who fully understands their farm and who first hears their goals and priorities. This type of work lends itself to pre-planned longer but less frequent visits, with additional remote support in between-times. It is not supported by the anxiety of the bill being governed by a ticking time-clock, or alongside task-based work or ministrations during a herd-health crisis. The time to mend the roof is when the sun shines!

What is the most profitable veterinary work? For you? For the farmer?

The answer to these questions might help unlock the path to the most sensible fee structures. For a farm veterinary practice, the most profitable professional work, excepting selling medicines, is pre-arranged work which can be resourced efficiently. For example, not requiring long driving times and short chargeable time on farm. For the farmer, the most economically justifiable element of the veterinary bill is preventative or production-related work likely to improve the farm's income, not interventions intended to limit loss. In other words, saving a sick calf with medicines and fluid therapy is a damage limitation exercise, and is costly and inefficient for both veterinary surgeon and farmer. Conversely, planning for, and delivering, high calf health and good feed conversion efficiency is an investment which will reduce the need for costly interventions as well as return a better future profit for the farm. If this can be delivered in a structured way with a regular income for the veterinary practice, for example on a contract basis, then it is a more efficient and profitable service to provide than an ambulatory crisis management/ire brigade service.

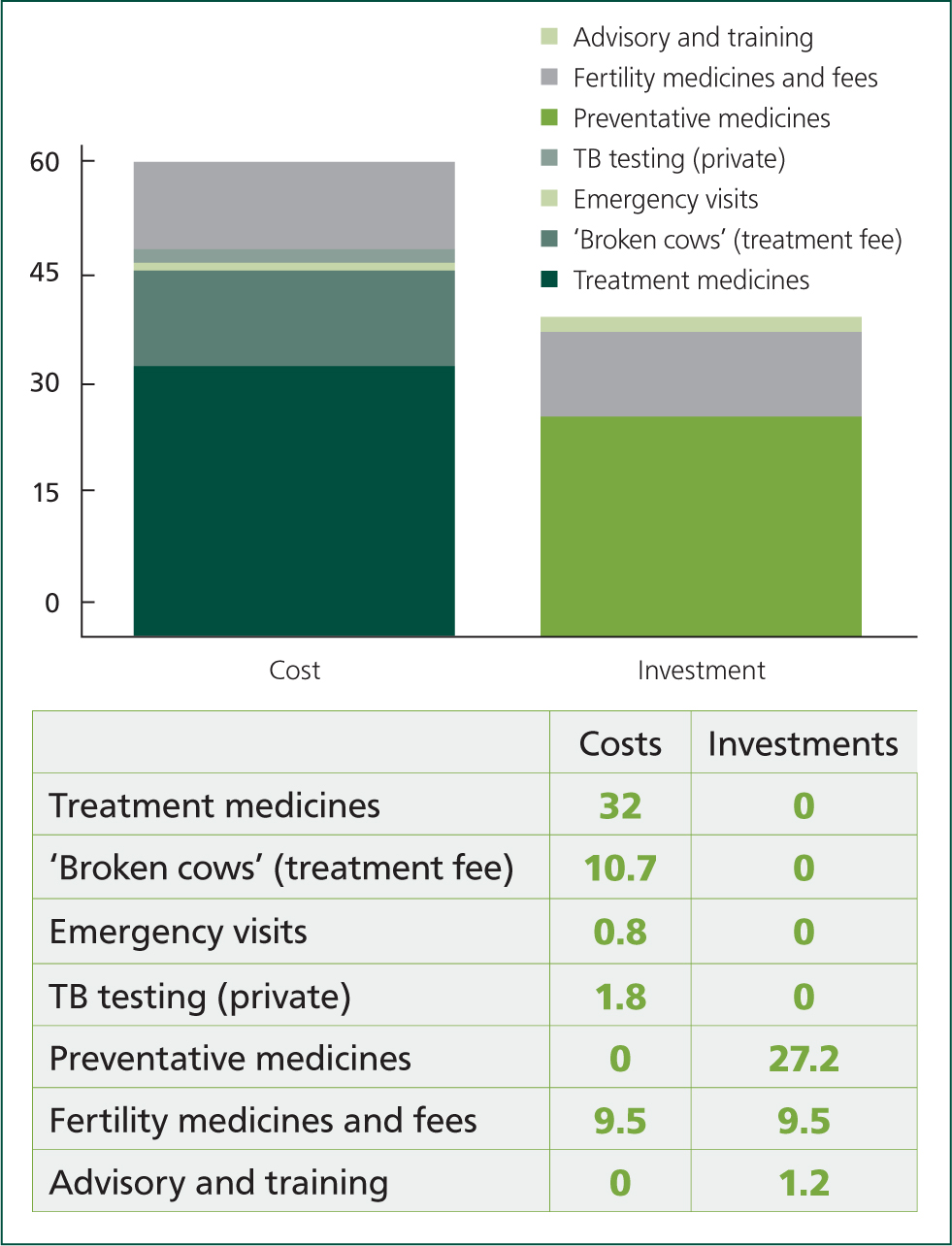

Figure 2 shows the division of a selection of dairy farmers' annual veterinary bills between the types of spend: investment and cost. ‘Investment’ includes advisory time, training and preventative medicines, plus 50% of routine fertility visits. ‘Cost’ includes all medicines used for treatment, all fees relating to treating sick animals/performing damage limitation and the remaining 50% of fertility visits. The fertility visits have been thus split to reflect that a high proportion of time spent on these visits is treating non-cycling cows or other damage limitation tasks. The farms in this survey spent a meagre 1.2% of their veterinary bill (which equated to less than £1 per cow per year) on advisory work, including herd health planning, and training.

It may be a common trap for veterinary practices to tailor their charging structure to suit famers who are using them predominantly for damage limitation. This tends to cater for the lowest common denominator. Many farm veterinary surgeons seem to aspire to do more advisory work, yet we seem poor at marketing ourselves in this way. Part of the marketing effort should include making it clear what we can achieve and at what price.

Remnant (2020) questions the viability of providing emergency services to farms while charging in the piecemeal and cross-subsidised way that it is usually done presently. Not only is it a financial burden to the practice, but it can have a heavy human cost too, particularly when an increasing gulf opens up between out-of-hours expectations for farm veterinary surgeons, compared with their companion-animal colleagues.

Evolving solutions

We might be able to learn from how other professional advisers structure their fees for farm clients. It is usually on a subscription basis. I suspect that a farmer's perception would be that their veterinary surgeon is more expensive than their consultant. There are two reasons why I believe this to be true. First, the monthly veterinary bill will typically be larger — obviously, it includes all the medicine purchases too. Second, and maybe more importantly, the farmer would likely be very aware of the veterinary surgeon's hourly rate, let us say £130 per hour, but not the consultant's. It is perhaps an absurdity to market ourselves with an hourly rate for all of our work (on farm), which inevitably sounds very high compared with an agricultural worker's rate of about £8.75 per hour, against which a farmer might benchmark him/herself.

I do not necessarily envisage a quick fix for how farm veterinary surgeons might charge more efficiently. Largely, as farms evolve, so do veterinary practices. However, it is just as important to be willing to drive changes as it is to be ready to adapt to change. It also seems sensible to be flexible with our approach.

I speculate that practices that evolve the fastest to offer more service contracts and to offer a greater range of services will be rewarded with greater success. An increasing number of farm practices now employ para-professionals (sometimes termed ‘vet-techs’) who enable an extended range of services to be offered. These include calf weighing, mobility scoring, assistance with vaccination, delivering calf vaccination programmes, debudding, freeze branding or foot trimming. This can result in an overall better offering to farms, as well as creating more income possibilities: a win-win.

To make a comparison which might resonate with the companion animal world, providing a calf health planning service which includes regular weighing, health scoring, benchmarking and routine vaccination, compared with trying to sell calf pneumonia vaccines alone, is the difference between providing pet weight-loss consultations with trained nurses, or displaying some packets of weight-loss diets in the practice waiting room. The former is likely to be far more successful for the pet, the owner and the veterinary practice.

Conclusion

There are many ways to charge for fees. Table 1 demonstrates there are pros and cons to all of them. However, we are in the midst of an inexorable trend towards monthly contracts in all walks of life. For example, many practices will have changed the way they fund motoring costs, moving away from outright cash purchase to contract hire, which often includes servicing and tyres. This allows the business to manage cash flow and budget very accurately. A good service provider also takes away a lot of the administrative headaches associated with running a small fleet of cars, such as ensuring vehicles are all taxed, MOT'd and regularly serviced.

Offering contract models, with or without medicines, might offer important advantages. They could provide an opportunity for shaping farmers' behaviours and the ways they use veterinary services. In turn, this could drive efficiency within practices and therefore better profitability: less tearing around the countryside in a blur of busyness, and an increased cow:veterinary surgeon ratio.

Subscription or contract models will be particularly attractive for farmers who can understand their veterinary spend as an investment rather than a cost. This is dependent on effective messaging: the principle of prevention rather than cure is perfectly sound and it needs to be presented coherently and convincingly. I believe a courageous change of approach to our charging models will be good for the next generation of farm veterinary surgeons, the future generation of business-focused farmers and the animals under our care.

KEY POINTS

- Farm veterinary practices are under intense price pressure for both medicines supply and professional fees.

- Cross-subsidy from medicine charges for emergency ‘fire-brigade’ and out-of-hours work is becoming less and less sustainable.

- Practices must be realistic about the costs of providing an emergency ambulatory service, both in economic and human terms.

- It is becoming more prevalent in all walks of life to pay a monthly subscription fee or contract for services; the model has many advantages to commend it and could be applied to veterinary services for farms.

- Veterinary care for commercial farm businesses must be sustainable economically, and this requires greater efficiencies of professional time; fewer but longer visits are one way to achieve this.

- Prevention rather than cure is sound from an economic, welfare and sustainability perspective. Farm veterinary surgeons must press this case more strongly.