Every student that embarks on the process of training to become the next veterinary surgeon commits to undertake 38 weeks of extramural study (EMS). EMS is divided between preclinical/animal husbandry, where the students gain an appreciation of different animal production systems, and clinical EMS, where they see practice with those of us at the proverbial coal face. Students will spend at least 26 weeks with veterinary surgeons in one form of clinical or non-clinical practice or another, and face many of the same challenges we face. These students will also have their own challenges and concerns such as assimilating lots of new knowledge, settling into a new team for a short time, often adjusting to a new location, and trying to make a good impression with us.

We as vets are also facing our own daily challenges. We have daily task lists, often too long with not enough time whatever our sector. We have the responsibility of everyone's safety on farm or in the room. We have our personal lives to balance with families and other commitments. We have the constant challenge of trying to deliver the same standards of care while meeting social distancing and PPE requirements. And some of us have the business to run and keep staff employed in difficult times. Unfortunately, as research shows (BVA, 2019), discrimination is another challenge many of us face that many others do not even recognise.

In the BVA report on discrimination in the veterinary profession (BVA, 2019), informed from two surveys, between 24% and 29% of respondents had experienced or witnessed discriminatory behaviour. Despite these statistics, 43% of veterinary employee respondents were either not very concerned or not at all concerned about discrimination in the profession. This number increased to 60% of the self-employed/owner/partner respondents. A legitimate limitation of the discrimination survey is that it was a self-selecting population. One would expect those with a concern would be more likely to fill out the survey, however, the report was formed from two surveys. The second survey informing the report was the BVA Spring 2019 Voices survey, a survey where the respondent group had self-selected but months prior and not with discrimination in mind. Furthermore, many of the respondents to the BVA surveys forming the report on discrimination (BVA, 2019), responded with ‘not very concerned’, suggesting not all respondents had a positive bias.

Why should discrimination within the profession be a concern? Besides ensuring we, as a profession, do not discriminate against people, because it is the morally and ethically right thing to do, discrimination has an impact on employee productivity and retention (BVA, 2017). When we let unconscious biases (unconscious prejudices against groups different to ourselves (Clohisy et al, 2017)) determine our hiring practices to exclude women, people of colour or the LGBTQ+ community to name a few, we create a homogenous workforce that is more likely to perpetuate the problem (Krook and Mindhe, 2014). We often hear the argument that we hire on merit alone — best person for the job — which is an admirable goal. But without tackling the problems of discrimination, unconscious biases and systemic biases that put up barriers to groups such as women and people of colour (Tacconelli et al, 2012), are we really hiring on merit at all? To improve retention, staff need to feel valued and supported. To attract the best candidates for roles and be a true meritocracy, applicants need to be considered fairly. Applicants from a minority ethnic background must send 60% more applications than white British applicants to get a positive response (CSI, 2019). Furthermore, from the student perspective, a good experience on EMS can attract more and better quality applicants.

At the University of Surrey, we undertook a similar survey to the BVA but focusing on students who had started their clinical EMS. We aimed to examine the types of discrimination experienced or witnessed, sectors of the profession it was occurring, and who was perpetrating the discrimination. The BVA survey reported that students were less likely to report discrimination than other members of the profession with just 19% reporting (BVA, 2019), so we aimed to answer the question of reasons why students are reluctant to report. Finally, we also wanted to gather student opinions on discrimination through a series of statements that respondents of the survey would select their agreement/disagreement. We conducted a cross-sectional survey of 3rd–5th/6th years of all UK and Irish vet schools from 4th March to 27th April receiving 407 responses of which 403 met acceptance criteria of being clinical EMS incidents. Associations were tested using Pearson's chi-squared test of association.

In our survey, 36% of respondents reported experiencing or witnessing discrimination. Incidents of discrimination were predominantly based on gender (38%), followed by ethnicity (16%) and age (15%). We conducted an analysis examining in further detail the characteristic-based discrimination as experienced/witnessed by specific minority groups. Under the category of age, older students experienced/witnessed significantly more ageist incidents than younger students (using 24 years as the divider).

‘As a mature student, I was told that I was selfish for taking the place of a younger student that would have had a longer career ahead of them. This was said by a farm vet'.

— mature student.

Students with a disability experienced/witnessed significantly more ableism than those without.

‘People making fun of depression and mental health issues being irrelevant’ — ‘people should just man up’

— student with self-declared mental health condition.

Students who were not white British experienced significantly more racism/xenophobia with 93% of BAME (black, Asian and minority ethnic) experiencing racism.

‘Xenophobia, both small and large animal owners/farmers, usually the farmers. They question if I can understand the concepts well enough or diagnose and treat as well as a British vet student. I feel like it will be a huge barrier if I wanted to work here and discourages me to stay here after graduation. I'm thinking of practicing at other English speaking countries after graduation'

— Turkish student.

Female students experienced/witnessed significantly more sexism/misogyny than male students.

‘Older male vet told me that I should be a housewife rather than a vet and said ‘you need to be strong to be a farm vet’ implying I couldn't because I'm a shorter woman. He also told me women should obey men'

— female student.

LGBTQ+ students experienced/witnessed significantly more LGBTQphobia that their heterosexual counterparts.

‘Multiple use of slurs against sexual orientation/gender identity/race on many occasions’

— female student self-identifying as queer.

Respondents within specific groups will be more vigilant to discrimination against them targeting that characteristic. Regardless of the extra vigilance, the mental impact of incidents will be significant (Pascoe and Richman, 2009).

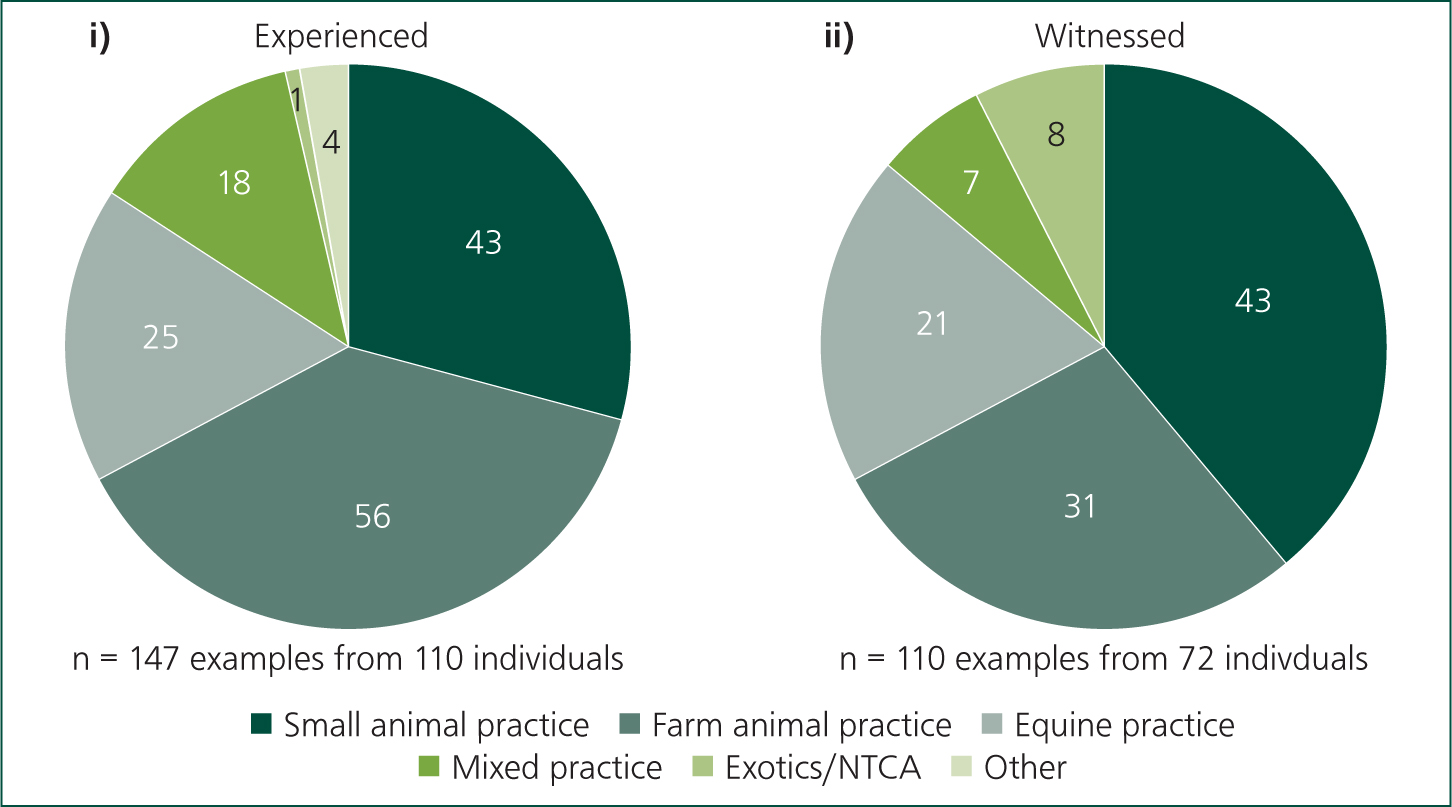

By profession sector, farm/production animal practice had the largest quantity of experienced incidents at 38% and the second largest number of witnessed incidents at 28% (Figure 1). Mixed practice incidents were 12% and 6% respectively. The perpetrators of the discriminatory behaviour or comments were vets (39%) and members of the public including farmers (37%). There was no statistical association between the sector of practice and the characteristics that discriminatory behaviour or comments were aimed at. However, by quantity of incidents of sexism, a common theme in farm animal practice was comments by farm vets and the farmers that women were ‘not cut out to be vets’ or were likely to ‘go off and have children’ or be ‘small, weak females’. When farmers were making inappropriate comments, vets were often either silent or perpetrators as well.

‘Farmer making those sadly ‘normal’ comments about me looking too young and being female so not physically able to do a good job. Asking the vet I was with why they let girls do this sort of work. Also I was very disappointed that the vet I was with (a younger male vet) did nothing to counter this view but just laughed along leaving me feeling very inadequate and hugely doubtful of my own abilities'

— female student.

Students were unlikely to report any discriminating behaviour or comments with only 8% of experienced incidents being reported. The most commonly selected reason with 39% of those not reporting was thinking that nothing would be done, followed by not knowing how to report (16%), and concern about the consequences of reporting (15%). Satisfaction with outcome when incidents were reported was mixed with 36% being satisfied, but with such low numbers (14 examples) it was difficult to draw any meaningful conclusions.

Student opinions on discrimination mostly followed expected patterns. The interesting points to raise are that students with specific characteristics were more likely to agree that discrimination against those characteristics was a problem. Essentially, those that experience discrimination will recognise it more readily and so should be listened to. In a statement saying that racial diversity should be increased in the profession, BAME respondents were over-represented in disagreement. This may be a concern about action taking the form of tokenism and fears that the genuinely needed support fails to be realised (Bleich et al, 2015). In response to professional bodies doing enough 55% were neutral, with even agreement and disagreement. Interestingly, male respondents were statistically significantly more likely to be either neutral or in disagreement about discrimination against different groups, and more likely to agree that enough is already being done. In fact, research has shown, that despite most of the profession being women, the professional structure and culture remains male-orientated (Knights and Clarke, 2019).

In the current professional structure, it is the men who will have fewer barriers to their progression within the profession. These students will currently be more likely to become the practice owners/partners/clinical directors/corporate CEOs of tomorrow — people who, with no ill-intent, genuinely believe that ethnic minorities just do not want to be vets due to cultural difference, or that women taking on the lion's share of childcare just do not have the same experience as men, or that vets with chronic illness or disability should not be in a clinical role. If there is not a diversification and better inclusion of difference within the profession, then the erroneous belief that discrimination is not an issue in veterinary medicine and that white, heterosexual males really are the best qualified and most deserving of senior positions will be perpetuated.

Finally, Daniella Dos Santos, President of the BVA, said at the Courageous Conversations Conference: ‘Every member of the profession has a role to play in creating and maintaining good workplaces, no matter their role or chosen sector, and regardless of whether they are an employer or employee’.