Bracken is one of the world's most abundant plants and has long been recognised as poisonous. It contains several toxic compounds and causes differing syndromes in animals. This article discusses bracken poisoning in cattle, sheep and pigs.

The plant

Bracken (Pteridium species) (Figure 1) is a genus of ancient, large coarse ferns. It is a very common and widespread plant that grows throughout the world (except where it is very cold or very dry). It is found in woods, heaths, sand dunes, neglected pastures, hedgerows, moors and even in walls, and is often dominant over large areas of light well-drained acid soils. It is found throughout Britain and Ireland, and is occasionally cultivated in gardens and parks. Bracken has large, highly divided leaves with rhizomes from which the fronds arise at intervals. In the past, the genus was commonly treated as a single species, Pteridium aquilinum, but it is now subdivided into about ten species.

Toxic effects

Bracken contains several toxic compounds including carcinogens (particularly ptaquiloside, a norsesquiterpene glycoside), thiaminase (an enzyme) and prunasin (a cyanogenic glycoside). Prunasin is usually present in harmless concentrations (Cooper and Johnson, 1998).

Bracken toxicosis in domestic animals has been well described (Evans, 1989) but causes different clinical syndromes in different species. Bracken poisoning in cattle has two main forms and is known by various names:

- Acute/subacute poisoning with rapid death is called acute haemorrhagic syndrome and consists of severe leucocytopenia and thrombocytopenia leading to widespread haemorrhage (Evans, 1989). In the past this condition has been referred to as cystic haematuria, cystic haemoangiomatosis or red water.

- Chronic bracken exposure causes enzootic haematuria or enzootic bovine haematuria and is characterised by tumours of the upper alimentary tract and urinary bladder. A similar condition has been described in deer (Scala et al, 2014).

- In addition to haemorrhage and cancer, sheep also develop retinal neuropathy, which can lead to permanent blindness (Barnett and Watson, 1970).

- Goats appear to be relatively resistant to bracken poisoning and are used to control it.

- The thiaminase in bracken can induce avitaminosis B1 in monogastric animals such as horses and pigs (Evans, 1976), and this condition is called ‘bracken staggers’. Avitaminosis B1 generally does not occur in cattle or sheep because rumen bacteria synthesise this vitamin.

Mechanisms of toxicity

Bone marrow suppression

Acute bracken poisoning occurs when animals ingest high doses over relatively short durations of weeks or months. It is characterised by depletion of bone marrow megakaryocytes followed by panhypoplasia. Affected animals have both an increased susceptibility to infection and a tendency to bleed.

The mechanism of the bone marrow suppression seen in cattle, and less commonly in sheep, is unknown. It is attributed to radiomimetic damage to proliferating bone marrow stem cells by ptaquiloside.

Carcinogenesis

Lower doses of bracken eaten over a longer duration are more likely to be carcinogenic. The effects seem cumulative, as animals are exposed repeatedly for years. Often the onset of clinical disease can be delayed for weeks or even months after animals have been removed from bracken-infested ranges and pastures. The carcinogenic potential of bracken and ptaquiloside has been confirmed in rats, mice, guinea pigs, hamsters, sheep, quail and toads (Evans, 1968; El-Mofty et al, 1980; Bringuier et al, 1995; Ramwell et al, 2010).

Ptaquiloside is a direct-acting carcinogen. It is converted in alkaline conditions to a highly reactive dianone intermediate that reacts with DNA to produce chromosomal damage, which can lead to the formation of neoplasms. Ptaquiloside and bracken-induced chromosomal aberrations have been demonstrated experimentally (Nagao et al, 1989; Lioi et al, 2004; Peretti et al, 2007). Alkaline conditions are required for the formation of the dianone intermediate and this may explain the location of the neoplasia seen (upper gastrointestinal tract and bladder) (Smith and Seawright, 1995).

Avitaminosis B1

In pigs and horses, bracken causes poisoning that results from induced thiamine deficiency. Thiamine is an essential vitamin involved in metabolism and in maintaining the myelin of peripheral nerves. Bracken contains a type I thiaminase, which does not destroy thiamine (as type II thiaminase does) but creates a thiamine analogue. This inhibits thiamine-requiring metabolic reactions and has an anti-thiamine effect that induces thiamine deficiency (Chick et al, 1985).

The highest concentration of thiaminase is in the rhizome (Vetter, 2009) and young fronds, but there is seasonal variation. The concentration of thiaminase in the rhizomes is high in autumn and winter, declining between January and April before it rises again from May. In the very young fronds, the concentration is high in April and declines from May as the aerial parts of the plant unfold. The concentration in the rhizomes in autumn and winter can be 20–30 times higher than in the fronds in June (Evans, 1976).

Circumstances of poisoning

All parts of the plant are toxic, but the rhizomes and the palatable young shoots are particularly toxic. Bracken remains toxic when dried, but bracken ash is not hazardous. Poisoning generally occurs in the late summer or early autumn, particularly in young animals as some develop a taste for bracken.

Bracken poisoning may occur in cattle:

- During periods of drought when other food sources are unavailable.

- When excess lush pasture is readily available and animals seek sufficient roughage.

- When they are fed hay or silage contaminated with bracken.

- When bracken is used as bedding (Hidano et al, 2017).

The concentration of ptaquiloside varies in different bracken populations (Smith et al, 1994). In places where the concentration is low (for example, some parts of India), the incidence of bladder problems is low (Dawra et al, 2002).

Clinical syndromes in cattle

There are two syndromes described in bracken poisoning in cattle: acute haemorrhagic syndrome and enzootic bovine haematuria.

Acute haemorrhagic syndrome

Poisoning only occurs after ingestion of bracken for several weeks or months, and can occur weeks after exposure to bracken has ended. This form of bracken toxicosis is rapidly progressive; death is common and generally occurs 1–6 days after the onset of signs (Anjos et al, 2008; Plessers et al, 2013).

Initial clinical signs are lethargy, inappetence, loss of condition, pronounced pyrexia and watery discharge from eyes and nose. This is followed by weakness, pale mucous membranes, rumen stasis and haematuria. In young cattle there is submandibular oedema with laboured breathing (roaring).

Haemorrhages vary from minor mucosal petechiae to effusive bleeding. There may be bloody nasal discharge, blood in the milk, vaginal bleeding, large blood clots in the faeces and excessive bleeding from minor cuts or insect bites. Death results from internal haemorrhage or secondary infection (Pamukcu et al, 1976).

In the initial phases, monocytosis may be pronounced and followed by granulocytopenia (including neutropenia) and thrombocytopenia. Thrombocytopenia and neutropenia are usually so severe that the animal does not survive. Initially there is mild anaemia caused by haemorrhage but then, in the terminal stage, the anaemia is the result of decreased cell production. The prothrombin time and activated partial thromboplastin time remain normal (Di Loria et al, 2012).

Postmortem examination of cattle that have died from acute haemorrhagic syndrome shows widespread haemorrhages including subcutaneous haemorrhage, necrotic lesions in the gastrointestinal tract, haemorrhages in the bladder, laryngeal oedema, hepatic infarcts (Hayston, 1946; Boddie, 1947; Anjos et al, 2008; Animal and Plant Health Agency, 2015), haematoma, ascites, hydrothorax, hydropericardium and bone marrow aplasia (Anjos et al, 2008; Sonne et al, 2011). Bracken may be found in the rumen.

Enzootic bovine haematuria

This syndrome occurs after grazing on bracken for months or years. The condition is more common in cattle more than 4 years of age (Pamukcu et al, 1976; Gava et al, 2002) and episodes can be precipitated by stress, such as during parturition or transport, and may last for weeks or months.

Enzootic bovine haematuria is characterised by intermittent haematuria. There is increased frequency of urination, proteinuria and increased white blood cells. Anaemia and raised urea and creatinine will be seen eventually. The urine may contain coagulum, which can block the urethra in males (Pamukcu et al, 1976). Final phases include marked thrombocytopenia with anaemia, leucopenia and hypergammaglobulinemia (Perez-Alenza et al, 2006). There is also increased plasma heparin activity, with an increase in mast cells and tissue infiltration of eosinophils, monocytes, lymphocytes and plasma cells. Urinalysis generally shows haematuria and proteinuria (Perez-Alenza et al, 2006).

The bladder lesions may persist for a prolonged period and may lead to inflammation, erosions and papillomatous growths. Ultrasonography may show thickening of the bladder wall, pedunculated and erosive lesions, but cannot be used to distinguish the different types of neoplasm (Hoque et al, 2002; Sandoval et al, 2002). Neoplasms of the bladder and/or the upper gastrointestinal tract may develop over a few years and different types of lesion may occur in the same animal (Sandoval et al, 2002). Signs in animals with gastrointestinal carcinoma include progressive weight loss, ruminal atony, cough, dysphagia, regurgitation, halitosis, diarrhoea, bloat, salivation and dyspnoea (Souto et al, 2006; Faccin et al, 2017).

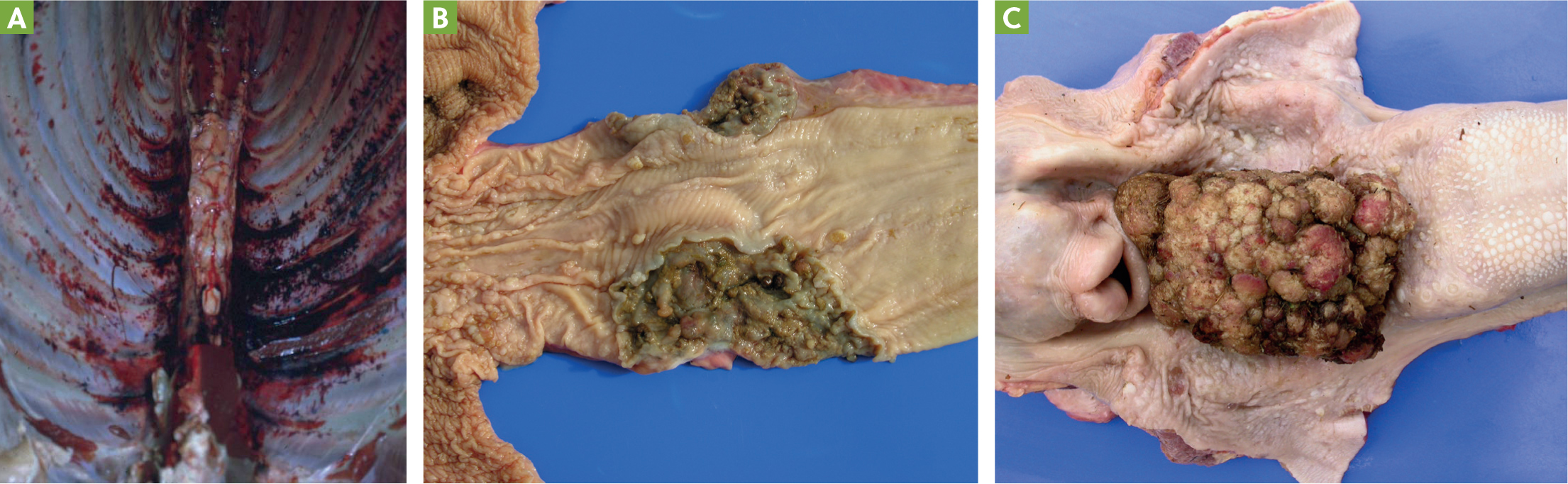

Postmortem findings in animals with enzootic haematuria show there is widespread haemorrhage in the carcass (Figure 2a) (Pamukcu et al, 1967; Pamukcu et al, 1976). The most common neoplasia is non-invasive papilloma but papillary or sessile types of transitional cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma or hemiangioma may occur (Pamukcu et al, 1967; Price and Pamukcu, 1968; Pamukcu et al, 1976; Marrero et al, 2001; Carvalho et al, 2006). There may be metastases, commonly to lymph nodes, but also lungs and other organs (Pamukcu et al, 1976). The same animal can have both epithelial and mesenchymal tumours in the bladder (Carvalho et al, 2006) and multiple sites may be involved (Pamukcu et al, 1976; Carvalho et al, 2006).

Blood vessels in affected areas are dilated, with proliferation, perivascular fibrosis, degeneration of muscle layer, thickening of the wall, endothelial activation and degeneration, and occasional necrosis of the vessel wall (Oliveira et al, 2011).

Gastrointestinal cancers are generally found from the base of the tongue to the pharynx or near the cardia and the reticulum or rumen (Gava et al, 2002; Souto et al, 2006; Masuda et al, 2011). They can range from papillomas or sessile types, transforming papillomas to squamous cell carcinoma (Figures 2bandc) (Gava et al, 2002; Souto et al, 2006). There may be lesions at more than one site and it can occur in the absence of bladder lesions (Gava et al, 2002). There may be metastases, mostly to the lymph modes (Souto et al, 2006; Masuda et al, 2011), but also the liver, lungs and spleen (Souto et al, 2006; Masuda et al, 2011).

Clinical syndromes in sheep

There are three forms of bracken poisoning seen in sheep and they may have more than one syndrome.

Acute haemorrhagic syndrome in sheep

Poisoning only occurs after grazing on bracken for several weeks or months and can occur weeks after exposure has ended (Moon and Raafat, 1951). Initially there is lethargy, inappetence, loss of condition and pronounced pyrexia. This is followed by weakness, pale mucous membranes, rumen stasis and haematuria.

Haemorrhages vary from minor mucosal petechiae to effusive bleeding. There may be bloody nasal discharge, large blood clots in the faeces and excessive bleeding from minor cuts. Laboratory findings include leucopenia, thrombocytopenia and anaemia (Sunderman, 1987). Death is a result of internal haemorrhage or secondary infection.

Progressive retinal degeneration (bright blindness)

This is the most well documented disorder of bracken poisoning in sheep. A progressive irreversible degeneration of the neuroepithelium of the retina of sheep can occur after bracken has been eaten for at least 4 months (Hirono et al, 1993). It is characterised by dilated pupils, lack of pupillary response to light, a glassy-eyed appearance and increased reflectance of the tapetum lucidum (‘bright blindness’). Examination of the eyes with an ophthalmoscope may show narrowing of the blood vessels.

These changes have been reproduced in sheep fed both bracken and the toxic component ptaquiloside (Barnett and Watson, 1970; Hirono et al, 1993; Hirono et al, 1993).

Cancer

Bracken-induced cancers are far less common in sheep but have been produced experimentally. Initially there is chronic haemorrhagic cystitis with subsequent bladder cancer. Cancer of the jaw and rumen may also occur in sheep (McCrea and Head, 1981).

Postmortem findings in sheep

Haemorrhages, retinal changes and/or carcinoma may be seen in the same animal.

Internal haemorrhages and blood clots; petechial haemorrhages of the abomasum wall and extensive areas of congestion; haemorrhages of the kidney, spleen, lungs, bladder wall and heart (Moon and Raafat, 1951; McCrea and Head, 1981; Sunderman, 1987; Hirono et al, 1993). Paracentral necrosis of the liver and haemosiderin in the spleen has been described (Sunderman, 1987).

In sheep with bright blindness, changes in the eye are confined to the retina with loss of rods and cones. The outer nuclear layer is destroyed (Hirono et al, 1993). Inner retinal layers and the pigment epithelium are unchanged (Barnett and Watson, 1970).

Chronic haemorrhagic cystitis and bladder cancer may be seen in sheep that are exposed to bracken. Tumours in the jaw (maxillary and mandibular fibrosarcoma) and rumen may also occur (McCrea and Head, 1981).

Clinical syndrome in pigs

Avitaminosis B1

Bracken poisoning in pigs is rare, probably because they are less commonly reared out of doors than cattle and sheep. It is also claimed that pigs are useful in clearing bracken-infested land as they root up rhizomes and trample the fronds (Evans, 1976), but suspected cases of bracken poisoning have been reported in pigs (Edwards, 1983; Harwood et al, 2007; APHA, 2019; Waret-Szkuta et al, 2021) and produced experimentally (Antice Evans et al, 1963; Evans et al, 1972). In an experimental study in pigs, faecal thiamine excretion ceased within 24 hours of pigs being fed bracken rhizomes (Antice Evans et al, 1963).

Signs reported in pigs include anorexia, depression and respiratory distress. Ataxia is reported occasionally. Affected pigs often succumb suddenly (Evans et al, 1972; Harwood et al, 2007; Waret-Szkuta et al, 2021). In an experimental study, pigs given a diet of 25% bracken rhizome became anorexic after approximately 18 days and this was reversed by parenteral thiamine (Antice Evans et al, 1963).

Postmortem findings in pigs with bracken poisoning are usually those of cardiomyopathy and heart failure, with subpleural and interlobular oedema of the lungs and pleural and pericardial effusion (Evans et al, 1972; Harwood et al, 2007; APHA, 2019; Waret-Szkuta et al, 2021).

Effects of bracken on reproduction

There is limited information on the effects of bracken on reproduction. In mice it caused growth suppression, an increase in rib variations and retarded ossification of the sternum of the fetuses, as well as maternal weight loss in spite of increased food intake. These effects are likely related to thiamine-deficiency (Yasuda et al, 1974), which does not occur in bracken-fed ruminants. In rats, bracken reduced female fertility and weight gain during pregnancy, and adversely affected physical and neurobehavioural development in the offspring (Gerenutti et al, 1992).

In ruminants, bracken may cause fetal loss because of haemorrhage. There may be a risk to young animals because ptaquiloside is found in the milk of cattle fed bracken (Alonso-Amelot et al, 1996).

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of acute haemorrhagic syndrome is based on clinical signs, history of exposure and characteristic postmortem findings of widespread haemorrhage, gastrointestinal lesions and bone marrow aplasia. Diagnosis of enzootic bovine haematuria is based on clinical signs, history of exposure, and ultrasound and postmortem findings.

Diagnosis of bright blindness in sheep is based on history of exposure and characteristic clinical signs, postmortem findings and retinal changes. Similarly in pigs, diagnosis of avitaminosis B1 is based on history of exposure and characteristic clinical signs of thiamine deficiency.

Prognosis

Cattle

In cattle, once clinical signs of acute haemorrhagic syndrome are present, mortality is high even with treatment. In an outbreak in Brazil, 47 of 203 cows (23%) died (Sonne et al, 2011) and in an out-break in South Africa, in a herd of 183 cattle, 55 developed signs and 28 died (51% of symptomatic animals). Cattle with leucocytes <2000 mm3 (<2x109/L) and platelets <50,000 mm3 (<50x109/L) are likely to die (Evans, 1989). Enzootic bovine haematuria is a progressive disease with a fatal outcome.

Sheep

There is more limited information in sheep and many cases of acute haemorrhagic syndrome are only diagnosed after death. In a field case of bracken poisoning, ill-thrift was still present 3 months after sheep were removed from the source and some sheep still had anaemia and lymphopenia (Sunderman, 1987). Bright blindness from bracken exposure in sheep is irreversible and progressive. In many cases, bracken-induced carcinoma in sheep is only found at postmortem examination.

Pigs

There is more limited information on the prognosis for pigs after bracken poisoning. In a recent outbreak of bracken poisoning in a herd of 85 pigs, 6 animals died following intoxication (before or after treatment with thiamine) and 6 animals recovered. Thiamine did not reverse the loss of initial body condition (Waret-Szkuta et al, 2021).

Treatment

The treatment of bracken toxicosis is supportive. Animals should be removed from exposure to bracken as soon as poisoning is suspected. Prevention of bracken exposure is outlined in Box 1.

Box 1.Preventing animal exposure to bracken

- Ensure adequate forage is available.

- Even if the bracken has been slashed, ploughed or burnt there may be regrowth of young stems, or rhizomes may be exposed.

- Bracken fern density can be reduced by regular cutting, crushing, rolling or deep ploughing, or with the use of herbicides.

- Seek specialist advice.

- Legislation may be in place to protect some land areas; bracken is an important habitat for invertebrates, moorlands birds, reptiles and mammals (Figure 3). Some woodland plants grow under bracken.

- Steps may be required to protect watercourses and wildlife.

- Workers require protection from spores (they have been shown to cause damage to DNA in vitro (Simán et al, 2000) and may be carcinogenic).

Acute haemorrhagic syndrome

Antibiotics may be required for secondary infection, and blood or platelet transfusions can be considered, but a large volume may be required. Treatment is ineffective in most cases.

Enzootic bovine haematuria

Treatment is supportive but humane euthanasia is usually necessary in animals with advanced disease.

Progressive retinal degeneration (bright blindness) in sheep

This condition is irreversible. Animals can survive in familiar surroundings if provided with food, but humane euthanasia may be required in animals that fail to thrive.

Carcinoma

This condition is also irreversible and humane euthanasia is required in animals with severe signs.

Avitaminosis B1

In mild cases of avitaminosis B1, removing animals from exposure may be all that is required. Administration of thiamine (5–100 mg intramuscularly, subcutaneously or intravenously, depending on the formulation) can be considered and may prevent further deaths in a herd of affected animals (Waret-Szkuta et al, 2021). Good nursing care and high-quality feed should be provided.

Conclusion

Bracken is a common fern containing various toxic compounds producing various clinical syndromes in different species. Signs occur after weeks, months or years of exposure to bracken. Most cases occur in cattle that develop acute haemorrhagic syndrome or enzootic bovine haematuria. This conditions also occurs in sheep, along with retinal neuropathy. Monogastric animals such as pigs develop avitaminosis B1. Treatment for the various clinical syndromes is supportive but usually futile, except in the case of avitaminosis B1 for which thiamine supplementation can be given with positive results.

KEY POINTS

- Bracken poisoning of livestock has been recognised for centuries.

- Grazing on bracken causes various clinical syndromes in different species.

- Monogastric species develop an induced deficiency of thiamine (vitamin B1).

- Cattle develop an acute haemorrhagic syndrome and enzootic bovine haematuria with neoplasms of the bladder and/or the upper gastrointestinal tract.

- Sheep are at risk of acute haemorrhagic syndrome, progressive retinal degeneration (bright blindness) and neoplasia.

- Treatment of avitaminosis B1 is thiamine supplementation but treatment for the other syndromes is supportive only, because the conditions are progressive and humane euthanasia may be required.