Farmers often overreact to conditions affecting the skin because the clinical signs can be so dramatic. It is therefore important that the clinician is able to recognise the major disorders of the skin and advise appropriate treatment plans. As a few of the disorders of the skin are self-limiting, it is also an opportunity for the clinician to demonstrate that antimicrobial treatment is not required. There are as many conditions of the pig's skin as there are in dogs and cats, and this article cannot cover them but a reading list is provided at the end of the article.

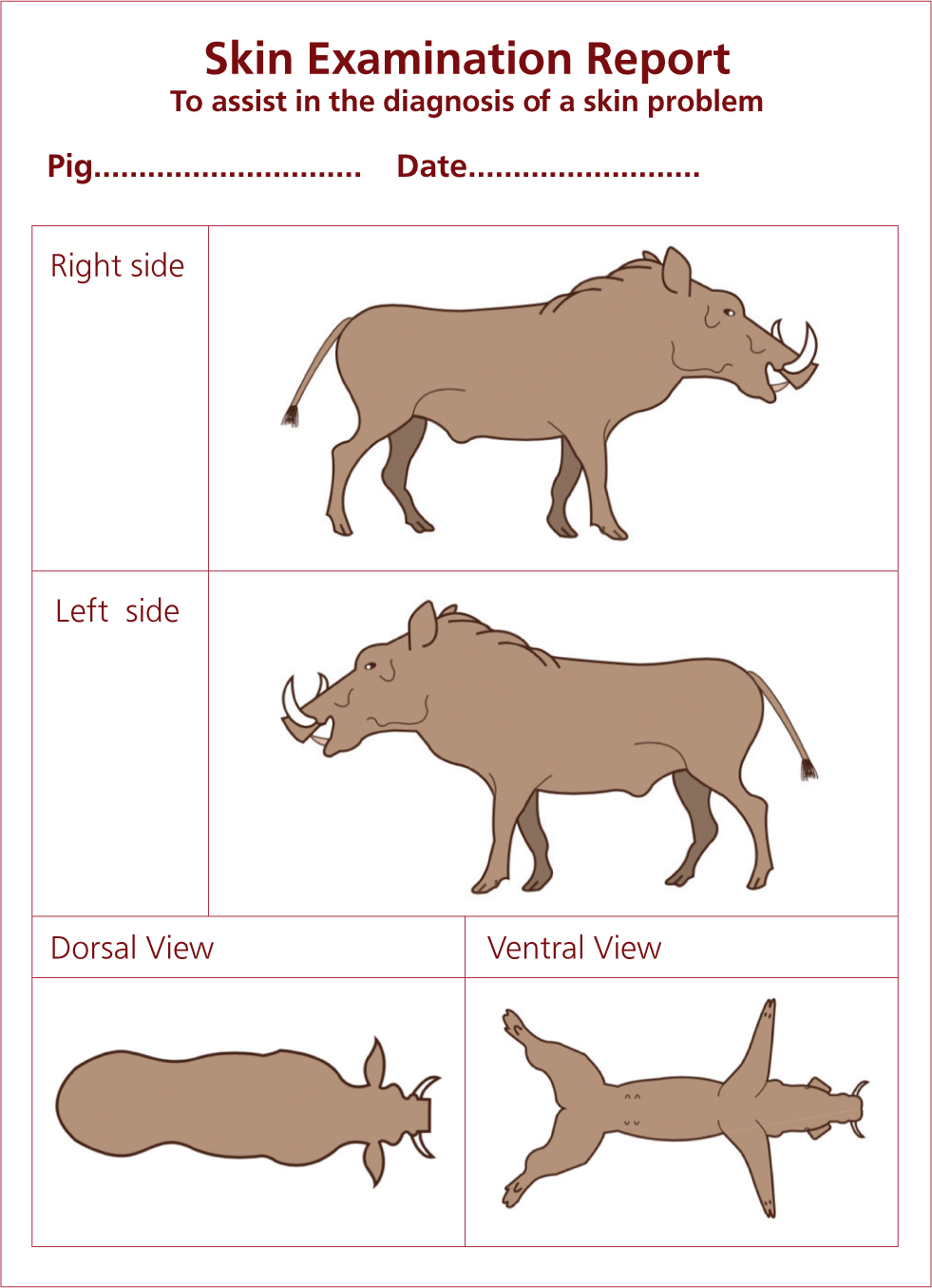

The position of the lesion on the pig can be very important in the differential diagnosis of disorders of the skin and a simple examination chart can be very revealing. The drawings can be customised for different breeds and even species — Figure 1 is for skin examination of the wart hog.

The control of many skin conditions in pigs relies on providing a clean hygienic environment with non-abrasive floor surfaces. Excellent floor cleaning, detergent and disinfection protocols should be instigated. A selection of disorders of pig's skin is described below.

Abscesses

Pigs are prone to abscesses (Figure 2). Subcutaneous abscesses can be very large and may contain up to 6 litres of purulent material. The presence of an abscess can be confirmed by inserting a long clean needle into the softest part of the ‘lump’ and drawing back with a 10 ml syringe to reveal a yellow creamy liquid. If the abscess contents are fluid, these can be released using a crosscut at the bottom of the abscess, not at the point (top). It is essential that the skin wound does not heal too fast as the abscess will reappear, hence the use of a crosscut. The cut at the bottom allows adequate drainage; no pocket of abscess should be left. This should be flushed with running water using a hose 2–3 times daily. If necessary, antibiotics may be injected via the intramuscular route to reduce secondary infection and pain management provided.

Allergic/atopy response

Pigs can become allergic to compounds. This is generally an issue with pet pigs. Investigate the cause of the allergic response in a similar manner to an investigation into an atopy.

Chemical dyes in bedding are quite often the cause in pet pigs (Figure 3). However, food and pollen allergies have also been observed. If the cause can be identified, the allergic cause would ideally be removed from the pig's environment.

Chemical/lime burn

Chemicals are often added to the floor and surfaces as part of the terminal cleaning and disinfection routines on pig farms. Lime (CaO) is a cheap and common disinfectant. However, if these chemicals are not allowed to dry adequately and pigs are then exposed to wet surfaces, the chemicals can burn their skin. The lesions are concentrated on the hind quarters and ventral surfaces, especially the face and rump (Figure 4). The tongue may also be burned. The pigs will normally recover within a week but pain management is advised.

Unusual skin conditions associated with chemical poisoning can also become apparent and must be investigated in detail. It must be noted that antibiotic intoxication with tiamulin may be a differential example.

Erysipelas

Erysipelas is the classic diamond disease of pigs which every clinician is expected to recognise (Figure 5). Erysipelas of pigs is caused by the bacteria Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, which is common in soil samples and, therefore, can enter the farm through the feed or water supply; when grain is harvested, 1–2% of the weight is soil. The organism also lives in fish, and fish meal can be an infected source. The organism can cause problems in turkeys and sheep, which can then cross-infect pigs on farms where birds, sheep and pigs are farmed together. In addition, 20% of the pigs on the farm may carry the organism on their tonsils without any clinical signs.

There are over 25 serotypes but types 1 and 2 are the most common and commercial vaccines only cover types 1 and 2. The disease is recognised around the world and is also called diamond skin disease, or measles by farmers. Erysipelas is one of the major diseases of the pig and its clinical signs should be recognised by all clinicians.

Erysipelas can affect any age group. However, most weaners below 12 weeks of age are protected by colostrum antibodies passed on from their mother.

The acute phase of erysipelas is when the pig presents with the classic diamonds (Figure 5). The disease appears to start with a sudden onset. However, it takes 2–3 days post infection for the pigs to demonstrate the classic diamond lesions of erysipelas. The ‘diamond’ lesions may be felt before they are seen. Affected animals present with a high temperature (40–42°C). Infected pigs often separate from the rest of the group and may appear chilled and cold (typical of a high fever). When you examine the group of pigs, the affected pig will generally be found lying down and when encouraged to rise, will walk stiffly with the appearance of a sore abdomen and may be tucked up. The affected pig will then attempt to find an area to lie down again and generally appears very dejected.

Associated with the pyrexia (high body temperature):

- Sows may abort

- Boars may become infertile, which may be permanent or last 6 weeks.

Acute pigs left untreated may die or start to recover in 4–7 days.

Post-mortem lesions

In peracute cases, there may be very few lesions visible. It is possible that an enlarged spleen may be seen (Figure 6) and the diamond lesions may be felt (but not seen). Note swine fevers can also create a very enlarged spleen.

Treatment of individuals or a group

Acute/subacute erysipelas Penicillin and tylan phosphate-based medicines are effective in treating erysipelas. Acute cases should also be given analgesics.

Prevention and control

Erysipelas is easily and effectively controlled by vaccination. The vaccine is generally cheap. Injectable and oral vaccination is possible. Vaccination protection lasts about 6 months; therefore, the following programme is recommended:

- Vaccinate pigs over 3 months once and again 3 weeks later

- Selected breeding animals should be vaccinated at selection

- Vaccine sows either pre or post farrowing or every 6 months. If the sow is vaccinated pre-farrowing, it will boost her erysipelas colostrum antibodies and further protect her offspring

- Boars are vaccinated every 6 months but unfortunately vaccinations are often forgotten.

Poor vaccination may also result in unvaccinated pigs that are believed to be covered; the classic reason vaccines are inactivated is that they are frozen in a poorly maintained refrigerator.

Zoonotic

Erysipelas can infect humans and usually results only in a skin infection; however, the condition can be more severe.

Exudative epidermititis

Greasy pig disease — or more technically exudative epidermititis — is associated with Staphylococcus hyicus (Figure 7). This bacterium is normal on pig skin; it is found in the vagina and the piglet's skin is colonised at birth. The clinical disease is caused by this normal bacterium being ‘injected’ into the skin through fighting. Therefore, to understand the problem, the clinician needs to examine the farm for areas of aggression. Lincomycin can be a good treatment choice.

The major clinical signs are seen in piglets and weaners less than 8 weeks of age (pigs less than 20 kg bodyweight) (Figure 8). Treponema pedis may also be isolated from cases of facial necrosis.

Hyperkeratinisation/flaky skin

It is not unusual for adults to present with dry flaky skin (Figure 9). Mange as a cause should be ruled out by treatment. If the flaky skin presents a problem, to the owner generally more than the pig, the pig can be washed with a skin disinfectant. Cooking oil/olive oil may be added to the pig's diet to increase fat content, which will be expressed on the skin. Several pet pig diets are quite basic in order to reduce calories, prevent pigs from putting on too much weight and keep costs down, and are thus short in essential oils.

Jaundice-icterus

Jaundice (icterus) is a yellow discoloration of the skin/tissues (Figure 10), which may be seen pre-mortem in the white of the eyes or the mucosal surface of the vulva, but is often diagnosed post mortem. It is caused by a build-up of bilirubin pigments in the tissues. This build-up can occur as a result of liver disease (hepatitis, Leptospira icterohaemorrhagiae), gall bladder disease or blockage (gall stones), or associated with an excessive haemolysis (Mycoplasma suis).

Lice and ticks

The pig biting louse is Haematopinus suis (Figure 11). These are the biggest lice known to man and are readily observed. The lifecycle occurs on the body and takes 30 days to complete from egg to adult; however, the louse cannot live for more than 3 days away from the pig, making control technically easier than with mange — although in practice, this has proven more difficult. It is possible that swine pox may be carried by lice. Lice are very sensitive to standard mange (Sarcoptes scabiei), with treatment including avermectins.

A few ticks can be found on pigs, especially pet pigs or outdoor units. The major tick of concern in pig farming is the Ornithodorus (soft body) tick, which acts as a host for African swine fever virus.

Mange

Mange is a serious parasitic infection of the pig caused by Sarcoptes scabiei var. suis (Figure 12). This is a species adapted to the pig. Other sarcoptes mites may be found on pigs but they are of little significance. S. scabiei var. suis is extremely common and could be assumed to be present on all farms, unless an eradication programme has been undertaken.

The pathogen is spread via pig-to-pig contact and pigs coming into contact with infested buildings. The mite is able to survive 21 days off the host in ideal situations. The condition can have high economic importance. The impact varies depending on infestation, but a loss of 10% growth rates is not unusual in moderate-to-severe infestations. Mange will weaken the pig and is an added stress. The constant rubbing also causes damage to buildings. It may appear to occur cyclically with various degrees of stress on the pigs. Ear wax increases, sometimes forming plaques. As the condition becomes chronic, hair will be rubbed off in places and the skin may thicken. Areas of the skin may become traumatised and this can result in a secondary exudative epidermititis outbreak. Chronic skin lesions are more common behind the ear (Figures 13 and 14) and tail head. Mange affects all age groups, although sows and growing pigs most often exhibit the characteristic clinical signs. The problem may be more apparent in the cooler months.

The skin itching and subsequent skin damage is a secondary hypersensitivity reaction to the mange mite. As the S. scabiei may not be found in the damaged skin area, the clinician needs to examine the ear wax. Individuals need to be examined for evidence of the mite to confirm diagnosis. Absence is very difficult to ascertain.

From a commercial point of view, physical examination of the skin of finishing pigs in the slaughterhouse can be useful as part of the monitoring programme.

Treatment

Avermectins can be used via various routes, with injection and feed being common ones. Failure to adequately treat large boars is a common reason for failure to provide adequate control.

Control/eradication

Where possible, mange should be eradicated from units. Mange should be considered a welfare problem and, with avermectins, it can be eliminated from all units. There will be a need to purchase animals from sarcoptic mange-free farms.

Photosensitisation and sunburn

Photosensitisation and sunburn are associated with sloughing of the skin, generally in minimally pigmented areas of the body exposed to sunlight. The incident is normally triggered by the exposure (ingestion) of a photodynamic agent — for example, following the ingestion of parsnips (Pastinaca sativa) (Figure 15) or St John's wort (Hypericum spp.), classical causal agents. In many cases, the photodynamic agent is not recognised. Treatment should be systematic; hydrate the pig, provide pain management and remove from sunlight.

Swine pox

Swine pox or ‘pig pox’ is caused by the swine pox virus. This generally presents as small circular scabs that measure 10–20 mm in size (Figure 16). Occasionally, small vesicles may be seen. The pathogen is probably widespread on most farms, although the problem can appear as a herd epidemic. The pigs recover in 2 weeks. Skin disinfectant washes can be provided to control secondary infections and improve basic pen hygiene. A congenital form can present with lesions seen on newborn piglets (Figure 17). Pig lice have been associated with swine pox, but lice are extremely rare in commercial pigs.

Pityriasis rosea

Pityriasis rosea is a genetic condition which suddenly appears in weaned and growing pigs weighing 10–60 kg. The pig presents with scabby lesions on its body, the ventral abdomen in particular. The lesions are often in rings with a red raised edge and a blanched centre (Figure 18). With time, the lesions may grow and coalesce. The pig is not ill and grows normally; although it looks quite alarming, no treatment is necessary. Rarely does the condition present by the time of slaughter. It is wise not to breed from afflicted animals.

Porcine dermatitis and nephropathy syndrome

Porcine dermatitis and nephropathy syndrome (PDNS) is a peculiar problem which presents in older growing pigs and occasionally adults. The condition is associated with antibody overload, subsequent glomerular nephritis and a systemic necrotising vasculitis. This is recognised on the skin as a purple lesion (Figure 19). The condition is non-specific, but there is an association with farms having a problem with acute porcine circovirus associated disease (PCV-SD). The condition is suggestive of a type III hypersensitivity reaction. This condition was well recognised before porcine circovirus 2 systemic disease (PCV2-SD) was first seen and PCV2 may be of no clinical significance in affected pigs. PCV3 is being suggested as a possible agent, but this is unlikely. The condition is also not infective. In all farms, this can occur sporadically.

The most obvious clinical sign is the presence of irregular red-to-purple patches (macules and papules) in the skin, particularly around the hind legs and perineal area. The lesions tend to merge with time and if the pig survives, scarring may occur. The pigs also show anorexia and depression, and lie down. They may have a stiffened gait and possibly problems rising.

The problem classically affects pigs from 40–70 kg (12–16 weeks of age), although it has been seen occasionally in adults. In growing and finishing pigs, it is generally fatal within a few days of the first clinical signs (Figure 20).

Management

As yet, there are few effective clinical strategies. The best approach is to control PCV-SD by vaccination and ensure that water supplies are excellent.

Ringworm

Pigs with ringworm show characteristic round light brown gradually spreading circular lesions on their bodies (Figure 21). Healing can take several weeks. They otherwise demonstrate no undue clinical signs. For treatment, it is necessary to wash pigs with a skin disinfectant or, in a herd situation, consider the use of an antifungal such as griseofulvin.

Swine fever(s)

The practising clinician is not in the position to differentiate between classical swine fever (CSF; hog cholera) and African swine fever (ASF). While there may be pathological differences, they are subtle. Following a clinical examination, which indicates suspicion of a swine fever, the practising veterinarian should report this immediately to the government authorities and their practice. The swine fevers are both caused by viruses resulting in a severe systemic viraemia with death (Figure 22) and characteristically petechial haemorrhages in the skin (Figure 23).

With ASF, wild African suids are resistant to the disease, but wild boar (Sus scrofa) can develop a number of clinical signs. Mortality is the usual outcome for highly virulent strains. Acutely affected animals develop high fever with the pigs becoming very quiet and reluctant to move. Many pigs may vomit and present dyspnoea (as a result of severe pulmonary oedema) besides the haemorrhagic lesions. Sows will abort and lactating sows stop milking. In most cases, a haemorrhagic diathesis develops, with potential cutaneous haemorrhages, epistaxis and bloody diarrhoea.

Thrombocytopenia purpura

Seen only in young piglets from 3–10 days of age, the cause of thrombocytopenia purpura is the development of antibodies to the piglet's platelets in the colostrum of multiparous sows. Piglets present dead and, on close examination, reveal small haemorrhages on the skin (Figure 24). Post-mortem examination reveals small haemorrhages throughout the carcass. Surviving piglets should be transferred to another sow. This condition is a differential for the swine fevers but the age group is revealing.

Trauma of the skin

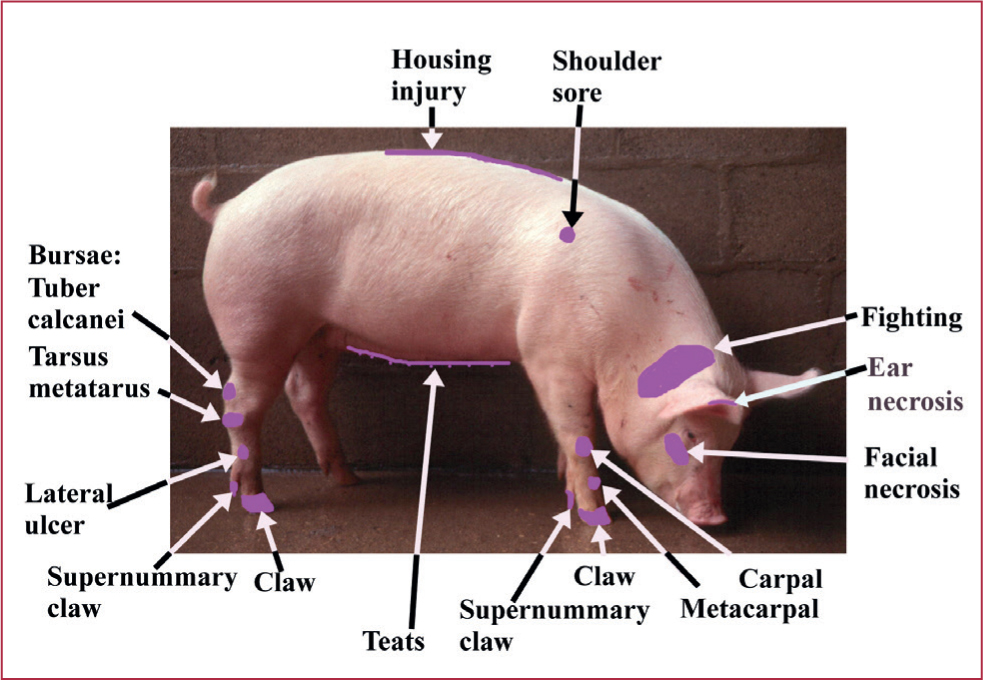

Trauma of the pig is unfortunately common. Typical locations of injury are illustrated in Figure 25. Trauma damage to skin can cause serious welfare issues in pig farms and cause considerable distress. Ear necrosis in particular is becoming a problem in nursery pigs. Treat trauma lesions aggressively and provide adequate pain relief. Ulceration may occur in other related species and require systematic care. For example, an ulcerated wound in a hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibious) (Figure 26).

Ventral/preputial gangrene

A spreading dry gangrene of the prepuce is seen in finishing pigs and young adults (Figure 27). The lesions start as a small ulcer, which rapidly develops into a black necrotic zone on the ventral surface around the prepuce. This can spread and become quite extensive on the ventral surface, extending into the scrotal area. Euthanasia may eventually be required. Treatment needs scrapes for spirochaetes. It may be possible to isolate T. pedis from these lesions.

Conclusions

Skin conditions are a common problem in pigs, and are often presented to the veterinary surgeon for resolution. While many conditions, such as exudative dermatitis and mange, are easy to resolve, conditions such as ear necrosis can be very problematic to fix. A correct diagnosis is required, and pain management essential. ASF should always be considered as a differential diagnosis and should be reported immediately to the approriate government authority.

KEY POINTS

- Skin conditions are a common problem presented to the veterinary surgeon.

- A clinical examination looking at the distribution of the lesions assist in the diagnosis.

- Many conditions can be easily resolved.

- African swine fever (ASF) has characteristic skin lesions, combined with clinical signs. It is vital that all veterinarians consider ASF as a differential.

- Sarcoptic mange can be eliminated on farms using avermectins and should be considered a welfare condition.

- Pain management is essential in treating skin issues.

- Ear necrosis and trauma cases can be problematic to resolve.