As veterinary surgeons in practice, we prescribe intra-mammary antibiotic for the treatment of clinical mastitis (CM) events in dairy cows under our care, and yet are often unaware of apparent cure rates or outcomes that are related to cases treated on farm. This can lead to some confusion when confronted by herd managers and herd owners and challenged to prescribe a different treatment when the efficacy of current therapy is perceived to be poor. As the focus on reducing antibiotic use in dairy herds continues to put the spotlight on mastitis therapeutics, reminding clients (and ourselves) of the importance of the FIRST CM case in a lactation becomes vital if we are to give structured guidance on mastitis treatment and prescribe in a responsible manner.

A recent guide (the Boehringer Mastitis Therapy Checklist) has attempted to provide a structured approach to the management of the FIRST CM case in a cow's lactation. This article tries to provide some clinical context and give guidance for veterinary surgeons when asked to respond to a farm client who reports disappointing outcomes from the treatment of clinical mastitis cases, with a perceived increased amount of recurrence. This article summarises this clinical discussion on improving the outcome when advising on mastitis treatment and gives a structured approach to this common clinical scenario.

‘Treatment failure’: establish the type of mastitis case

When challenged about apparent CM treatment failure on farm, it is important to first establish what ‘type’ of CM cases the client is treating — are these first clinical cases in lactation, recurrent clinical cases, particular cows that may be affected, severe clinical case presentations, cows with an increased somatic cell count (SCC) and so on. Clients may make no distinction between types of cases and it is important that veterinary surgeons do not simply prescribe a different intra-mammary product in the hope that this will improve the outcome and/or the overall incidence rate of mastitis on farm.

It is also very important that ALL cases of CM are being reported to a database (see below), irrespective of whether they have been treated with antibiotic. All MILD cases (i.e. changes to the milk only, ‘grade 1’), MODERATE cases (i.e. changes to the milk and swelling of the affected quarter, ‘grade 2’) and SEVERE cases (i.e. local symptoms accompanied by systemic signs of illness in the cow, ‘grade 3’) must be reported to allow an assessment of outcome.

Treatment failure: establish the prevalence of infection

In addition, any advice around mastitis therapeutics must be given in the context of the herd infection prevalence — in other words, are we discussing the treatment of CM events in a high SCC herd (>200 000 cells/ml and/or more than 20% of cows infected as measured by cell count) or a low cell count herd (<200 000 cells/ml and/or less than 20% of cows infected as measured by cell count)? For the former, the prevalence of Gram-positive pathogens such as Streptococcus uberis, Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus spp. will tend to be higher. In the latter, the prevalence of Gram-positive pathogens will tend to be lower, and the importance of Gram-negative pathogens such as Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp. and many others will increase. This is important when we consider the approach to the treatment of FIRST CM cases on farm and the likely outcome. For example, in a high cell count herd, a delay in the treatment of first cases with antibiotic may reduce the chance of cure as the likelihood of Gram-positive aetiology will be greater.

Treatment failure: establish definitions of outcome

Having discussed the CM cases being treated and the herd that they are being treated in, we next need to discuss how to define a ‘cure’ and what the client is measuring as an outcome. This will range from treatment failure (e.g. continued abnormal appearance of milk for 10 days after initial detection and treatment; Fuenzalida and Ruegg, 2019), worsening severity of CM (e.g. progression from grade I to grade 2 symptoms) or recurrence of abnormal milk in the same quarter after it had previously returned to normal.

Treatment failure: establish a timeline

The client may be expecting a quick solution but by agreeing at the outset that some investigation will be needed in order to provide informed advice, while addressing any immediate concerns regarding individual cows, the client is more likely to engage in the process. A conversation about the likely timescale and cost of the investigation may be useful at this stage. The investigation can be started immediately by gathering initial information and there are two key questions to remind ourselves and our clients:

- What is the outcome for FIRST cases of mastitis in a lactation? (‘cure’)

- What is the rate of FIRST cases in lactation, and is it possible to have fewer of them? (‘prevention’).

Both these questions require CM event data and (ideally) individual cow SCC data to answer. Gathering basic CM data is an essential part of the investigation; it is not possible to give properly informed advice on the treatment or management of CM without this information.

Investigation: getting the clinical mastitis event data

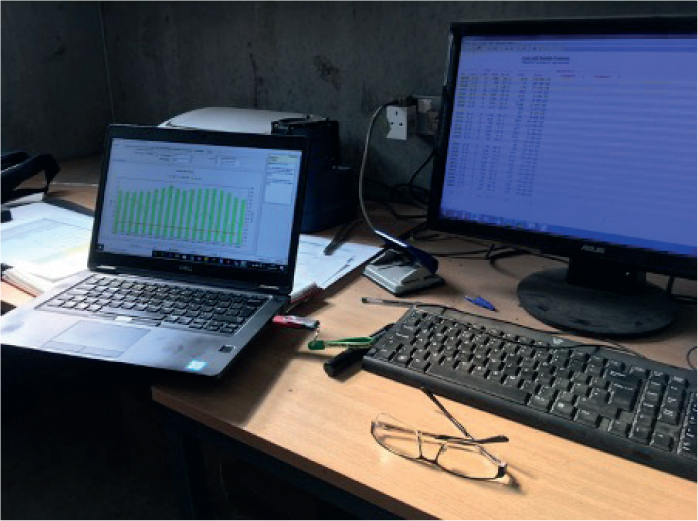

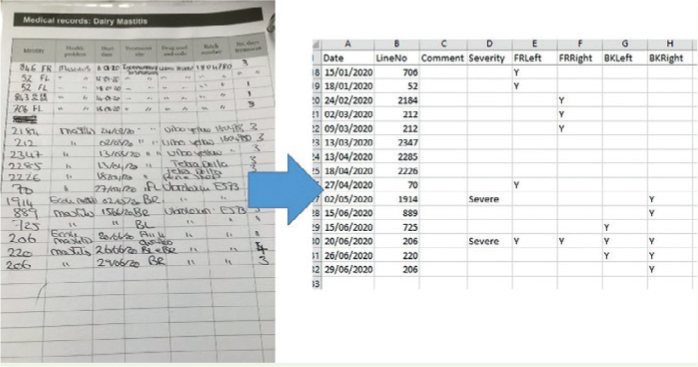

Prescribing antibiotic mastitis treatments to cows under our care assumes we are collating and analysing data pertaining to CM events to measure outcomes and crucially to avoid the need to use antimicrobials in the future. This latter point is the first of seven points on the British Veterinary Association's Responsible Use of Antimicrobials in Veterinary Practice guidelines and therefore prescribing antibiotics to treat mastitis must be done in the light of current data gathered on farm. This means we MUST already know where clients report CM events, for example are mastitis events reported to the milk recording organisation and therefore available as a download (CDL) file? Are mastitis events reported using on-farm software and therefore easily extracted? (Figure 1). Are mastitis events hand-written in a diary and therefore need to be routinely entered into a spreadsheet for ease of analysis? (Figure 2). The minimum data required are the cow ID (e.g. the line number), a calving date and the date of each CM event for an 18-month period to ensure any seasonality can be observed and the impact of the dry period on first cases investigated. More in depth information such as quarter(s) affected, severity and treatment selected are also useful but not essential.

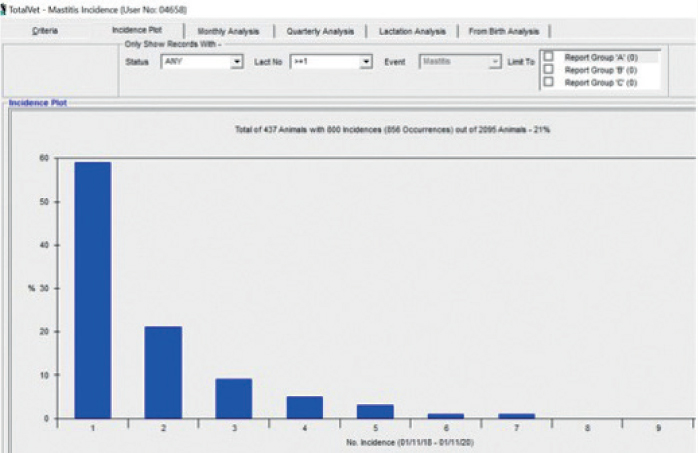

With this information, a distribution of CM events can be plotted, for example the percentage of those cows affected with CM that were reported with only one CM event (Figure 3). This can give an indication of treatment success for first cases and provide a clinical ‘cure rate’, provided recurrences of CM are reported irrespective of treatment. If individual SCC data are also available, a more robust definition of a cure can be used to calculate a cure rate, for example does the SCC fall below 200 000 cells/ml for several recordings following a clinical case? It is important that we are realistic in terms of what is achievable for first case cure rates, with 50 to 60% of all cows affected with CM affected once a good target. A large population of recurrent cows will therefore usually indicate a first case rate that is poorly controlled — in other words we focus on reducing the rate of first cases to reduce the impact of recurrence, rather than trying to chase very small increases in first case cure rate.

Most importantly, the collation and interpretation of CM events must always include an assessment of FIRST cases, particularly the rate at which cows are detected and reported with mastitis within the first 30 days of lactation, as this indicates dry period origin infections are likely to be important. We are often disappointed by the lack of reporting of CM case data to the milk recording organisations or to an on-farm database but need to ask ourselves is this because of a fundamental lack of feedback in outcomes and monitoring of first cases?

Investigation: the role of bacteriology

Too often in-practice bacteriology is seen as the beginning and the end point of mastitis monitoring and investigation work. Bacteriology is not the essential first step, but it is extremely useful as an ongoing monitoring tool. We highlight that the primary role of bacteriology is to understand the pathogen profile of the herd; submitting 10 CM samples twice annually is a good step to achieve this. We also highlight the importance of sampling clinical cases rather than samples collected from high SCC cows as this will improve the ‘hit rate’ and in particular the importance of collecting an aseptic sample from every FIRST case in a cow's lactation — these should be frozen pending enough to be sent as a ‘batch’ to a specialist laboratory for analysis and quality control.

Most importantly, we highlight the dangers of over-interpretation of a small number of bacteriology results, for example, the isolation of one or two isolates of S. aureus in a low SCC herd with clear seasonal patterns in new infection rate data and with very high cure rates across the dry period should not be allowed to move us away from a focus on environmental infection patterns.

Management of FIRST clinical mastitis cases: treatment

Armed with an understanding of first case incidence and cure rate and the likely relative prevalence of Gram-negative and Gram-positive pathogens, the veterinary surgeon is in a good position to give advice on treatment. Practicalities include:

- Prompt identification

- Collection of an aseptic sample and freeze

- Prompt treatment of first cases with intramammary antibiotic

- Aseptic infusion technique

- On-label treatment for first cases

- Administration of NSAIDs to all cases.

The duration of treatment and choice of broad or narrow spectrum treatment should be addressed in the light of herd cell count and outcomes of first cases to ensure all the factors that influence treatment success are covered. The Boehringer Mastitis Therapy Checklist is a useful tool to help the veterinary surgeon and farmer have this structured discussion and develop a treatment protocol that is optimised for the farm.

Reducing the rate of FIRST cases: prevention

While an optimal detection and treatment protocol for FIRST CM cases in particular is important, preventing first cases occurring should always be the aim and every time we prescribe lactating cow therapy we must be reviewing rates of first cases in herds under our care. By establishing where first cases predominantly arise, prevention measures can be targeted at the right area. If more than one cow is affected with a first case of CM within the first 30 days of lactation for every 12 cows that are eligible, the dry period should be the focus of attention. The new QuarterPRO initiative (https://ahdb.org.uk/quarter-pro) launched by AHDB Dairy in conjunction with the University of Nottingham and QMMS Ltd provides a route to understand the predominant mastitis pattern in a herd by using a novel pattern analysis tool (https://ahdb.org.uk/mastitis-pattern-analysis-tool). Using this pattern tool in conjunction with the appropriate resource material will give veterinary surgeons practical solutions to take to their clients and reduce the rate of new infection on farm.