With the rise in input costs putting ever higher pressures on profit margins, the end goal of successful calf rearing, to ensure a healthy and profitable animal that is reared in a time and resource efficient manner, has never been more important. Calf mortality remains high in the UK, with reports of 4.5% (Johnson et al, 2017) in dairy calves in the first 2 months of life, and a further 6.0% of dairy calves dying within 3 months of birth (Hyde et al, 2020). Calf housing has one of the biggest environmental and management impacts on health and welfare, and this will be explored here in this article.

There are multiple housing systems currently used to house and manage pre-weaning dairy calves on farms in the UK. These include a mixture of individual and group hutches, indoor pre-fabricated partition pens (Figure 1) or larger group pens within buildings (Figure 2), and outdoor pasture-based rearing systems. The cost of different housing systems varies widely, with individual calf hutches costing £200–400 each, group hutches for 10 calves costing £3000–8000 each depending on the make, and a shed for housing calves ~£80 000 depending on the size required. This should be borne in mind when advising farmers to change their calf housing type, as initial outlays may be considerable in larger farms.

Individual compared to pair or group calf housing

The selection of the type of calf housing used on farm can be influenced by many factors, with an understanding of farmer perspectives proving helpful in the provision of appropriate veterinary advice. Historically, the use of individual calf pens was recommended because of the perceived health benefits, with reports of up to 60% of UK herds using individual pens, and within Europe the number ranging between 40–100% (Marcé et al, 2010). It is true that biocontainment of disease, especially diarrhoea and respiratory pathogens, is best achieved through isolation of clinically affected individuals from a group (Barrington et al, 2002; Callan and Garry, 2002), but there is little evidence to support that increased group sizes directly result in more diarrhoea (Waltner-Toews et al, 1986; Reiten et al, 2019) or respiratory disease (Medrano-Galarza et al, 2018). That said, a recent UK dairy farmer survey indicated that the level of individual housing had reduced to around 38% (Mahendran et al, 2022), however, this was reported to be predominantly driven by milk buyer stipulations stating that calves must be in a minimum group size of two calves. This same survey also found that many farmers still held the misconception of reduced disease spread when using individual calf pens, with farmers stating that they also perceived that individual pens provided ease of feeding, with the ability to leave an individually housed calf unsupervised with its milk feed (potentially to try and save labour and time), and still be able to see how much milk it had consumed. Given that reduced feed intakes are often a sign of ill health in a calf, being able to identify these calves is important, and individual housing provides a relatively easy way to do this. If there is increased disease seen in group housed calves, it is likely to be related to poor feeding equipment hygiene e.g. multiple calves drinking from the same teat, or a result of poor feeding practices e.g. calves drinking from multi-feeders unequally. The other consideration around individual housing is the increased time and labour required for staff to tend them, along with outdoor systems often seen with hutches meaning that staff have to work outdoors, sometimes in very poor weather conditions. Ensuring staff have pleasant working conditions will generally result in more care and attention being given to the calves, enabling higher levels of health and management.

There is legislation surrounding the use of individual calf pens, stipulating that the maximum age limit for individual housing is 8 weeks old, and that calves kept in individual pens should still have direct visual and tactile contact with other calves (Council Directive 91/629/EEC and Council Directive 97/2/EC, and Welfare of Farmed Animals (England) Regulations 2000 (S.I. 2000 No. 1870) Schedule 4). However, the recent farmer survey found that 13.3% (11/83) of farmers who used individual calf housing admitted to only using pens that allowed visual but no tactile contact between calves (Mahendran et al, 2022). Thus not all UK farms comply with the legislation, and this, along with a change in public perception of acceptable animal care, is becoming a highly important driver for some key opinion leaders (including milk buyers and supermarkets).

In addition to public perception, there has been a plethora of mounting research looking at the benefits of pair housing calves (Figure 3). There have been demonstrable effects on pair housing and social learning, whereby the actions of a calf are influenced by watching or interacting with other calves (Keeling and Hurnik, 1996). Interaction promotes solid feed consumption, with pair housed calves consuming solids at an earlier age and in greater amounts compared with individually housed calves (De Paula Vieira et al, 2010), resulting in higher weight gains (Babu et al, 2004; Mahendran et al, 2021). Again, there has been no negative impact of pair housing demonstrated on disease prevalence (Chua et al, 2002; Jensen and Larsen, 2014; Mahendran et al, 2021). Calves housed in groups also demonstrate increased play behaviours, which is seen as a positive indicator of wellbeing (Spinka et al, 2001). These overall findings have led to some milk buyers including specific calf housing stipulations in their contracts — many contracts just follow Red Tractor guidelines that state housing must be of sufficient size to allow calves to lie down simultaneously, rise without difficulty, stretch and move freely without injury; there must be visual and tactile contact with others calves, and calves should not be housed in individual hutches/pens after 8 weeks of age. As a result of research findings around individual housing, some milk contracts now stipulate early grouping of calves must be done, such as Arla 360 and Marks & Spenser's farms being required to at least pair house by 21 days of age. These changes have already had significant impacts on farmer decision making around housing, and may motivate farmers to invest in their calf housing in order to ensure they comply with these new housing requirements.

Housing of calves in bigger groups can be labour saving for farm staff, with the addition of working under a roof increasing the level of protection from the weather. Calves can be fed via group teat feeders, but this makes individual intakes nearly impossible to assess. Use of computerised calf feeders can provide identification of individual calf feeding levels and drinking speeds, which can highlight sick calves up to 3 days earlier than calf personnel (Knauer et al, 2018; Conboy et al, 2022). Activity monitors can also be used for the early identification of sick calves (Cantor and Costa, 2022). When given near ad-lib access to milk, the author has found calves tend to average 1.3 kg of milk powder a day, or 8.5 litres per day, enabling excellent growth rates and robust immune systems. However, use of adequate weaning periods of 14 days from a minimum of 8–10 weeks of age should also be applied to ensure a smooth transition into solid feeds, and establishment of a functioning rumen to provide adequate digestion once milk is withdrawn, otherwise severe weaning checks may be experienced. It should also be noted that high milk intakes do result in more moisture in the environment and bedding through increased urine and faecal output, which makes excellent housing management all the more important. It also increases the time calves spend feeding and so the numbers of calves per teat should be kept low.

A commonly reported behaviour in group pens is cross sucking (Figure 4), which is a non-nutritive sucking behaviour that can lead to hair loss and inflammation, usually around the navel (Rushen and de Passillé, 1995), although it does occur on other body parts. Sucking is an innate behaviour, meaning that calves may be driven to suck on other pen contents or calves when the feeding methods result in very short periods of being able to suckle, i.e. from a bucket. Cross sucking can be decreased when calves are provided sufficient milk from teat feeders that limit the rate of sucking to extend feeding times over several minutes, or when calves can redirect their sucking motivation to a dummy teat on the wall of the pen (Veissier et al, 2002). There is evidence to suggest that there is an increase in cross sucking when calves are pair housed prior to weaning (Chua et al, 2002), but no effect on cross sucking occurrence during weaning or post-weaning in individually compared with pair housed calves (Costa et al, 2016; Wormsbecher et al, 2017).

The calf housing environment

Calves have a high surface area:body mass ratio, causing them to have an increased sensitivity to the cold, as well as having a lower critical temperature than an adult. The thermo-neutral zone of a calf up to 3 weeks old is 15–25°C (Webster, 1992), so below this the calf must utilise energy to maintain core body temperature. Within the UK, the average monthly temperature for 9 months of the year are below this threshold, meaning that cold stress is likely to be a significant factor for many calves. Radiant heat is also lost by the calf from its warm body relative to surrounding cold surfaces (Mitchell, 1976). This is particularly problematic if concrete is used for both flooring and walls because it draws heat away from the body of calves (Figure 5). Methods to reduce the impact of cold temperatures is through the use of calf jackets, as well as providing plenty of clean and deep straw bedding to allow nesting behaviours for warmth.

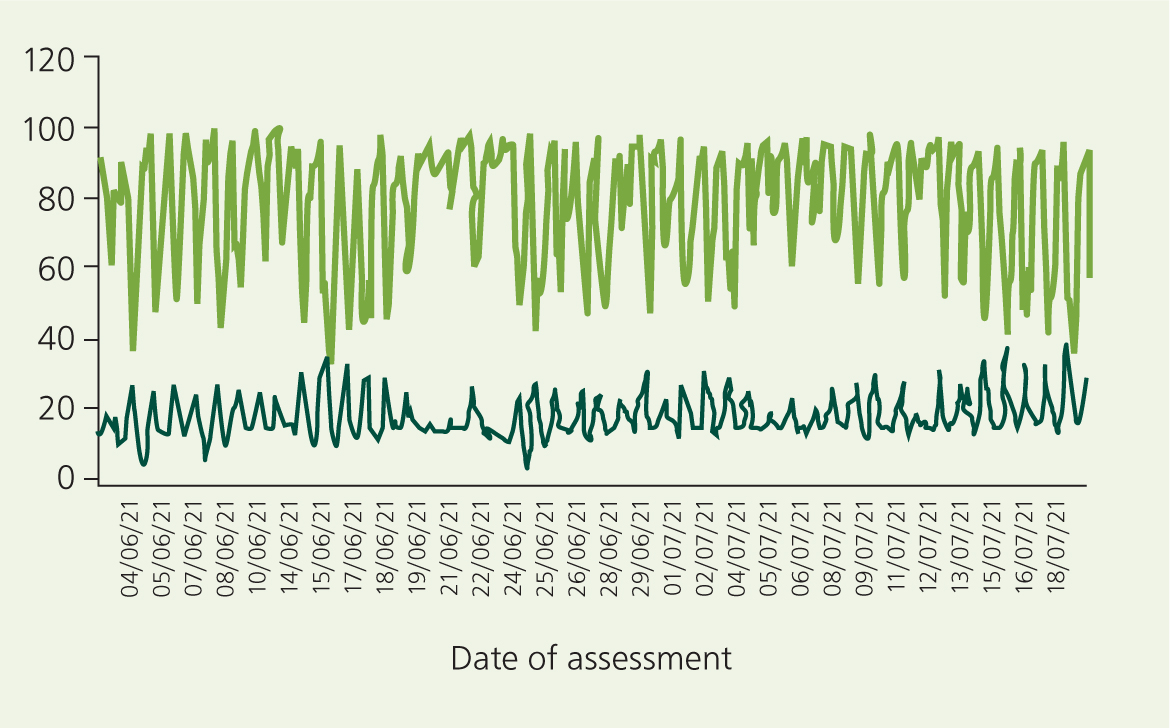

Conversely, heat stress is now also becoming a problem with increasing periods of high temperatures throughout the summer months in the UK. Figure 6 demonstrates the massive variation during the summer months in both temperature and humidity, with a maximum temperature of 38°C recorded in an individual calf hutch. Temperatures frequently demonstrated 10°C swings between day and night, which can be a predisposing factor for respiratory disease in calves (Callan and Garry, 2002). In addition, some housing types such as individual outdoor calf hutches in the summer have poor cooling abilities. This can result in them becoming hot and stuffy (Pálka et al, 2011), with temperatures up to 2°C higher than environmental temperatures (Hill et al, 2011).

Humidity is a measure of the actual moisture in the air, and within the UK it generally ranges between approximately 69–92% (Anon, 1990), but the target humidity level in a shed should be less than 70%. As seen in the Figure 6, the humidity was consistently reaching far above the target level during the cooler evening periods, with a maximum of 98% recorded. High humidity environments have increased air water droplet size, which allows them to carry more microbes (Curtis, 1972), with larger droplets also descending to calf height for inhalation (Parker, 1968), along with creating more condensation on the walls and roof of the building (Figure 7), and on the coat of the calves, which also decreases the insulating properties of the hair coat (Anderson and Bates, 1979). As complete control of humidity is only possible with fully enclosed, environmentally controlled housing, the only influence over this aspect is to ensure good ventilation with regular air changes of at least four (Bates and Anderson, 1979) to six per hour (Mitchell, 1976) in the winter, and up 30 air changes in the summer to reduce build-up of heat.

Ensuring good ventilation for provision of fresh, clean air to displace stale air is important because of its links with respiratory disease from build-up of ammonia, dust particles and air-borne bacteria (Lago et al, 2006; Louie et al, 2018). Assessment of ventilation is best done on a still day, using smoke bombs placed within the centre of a stocked calf shed and timing how long it takes to be eliminated from a building, which should be within 3 minutes. Other observations include assessing for the presence of cobwebs and thick dust layers across beams and rafters, indicating poor air flow within a shed. Calves <100 kg struggle to produce enough body heat to achieve the stack effect for ventilation of calf housing, so natural or mechanical ventilation must be relied on. The use of positive pressure ventilation tubes are associated with reduced odds of a calf developing pyrexia (Jorgensen et al, 2017), and generally will improve air movement in all shed designs. In addition, ensuring good drainage of fluids helps reduce moisture build up, with this being particularly important with calf hutches (Figure 8), as well as reducing bedding needs by keeping daily requirements low. Drainage is also important when washing and disinfecting pens between animals — ideally pressure washers or steam cleaners should be used, which produce a lot of moisture that must be removed from the direct housing environment. When portable housing units are used, such as hutches or igloos, ideally these will be taken away from the main housing area to facilitate washing.

The provision of adequate lighting is also important to enable good visibility of calves for signs of ill health, and to carry out routine tasks such as feeding and bedding (Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB), 2015).

Conclusion

The housing environment of a calf can have a big impact on their health, welfare and ease of management. Ensuring consideration is given to how a particular farm's housing system works within the climate and weather systems that it experiences will help veterinary surgeons to establish how the housing is impacting the health seen in the calves, and how these can be rectified to prevent diseases occurring. Quick, practical ways to check the housing environment include assessing cleanliness of the calves to indicate bedding hygiene, carrying out a knee drop in the calf bedding to check for moisture levels, using your sense of smell and feel to check for build-up of ammonia, dust and humidity within the air, and using your sight to look for signs of cobwebs and dust, which indicate poor ventilation. In addition, use of equipment such as temperature and humidity data loggers, smoke machines and anemometers for checking air speed can be very helpful for specific data collection.

KEY POINTS

- There are multiple housing systems used for calves across the UK, each presenting their own challenges.

- Moving from individual to group calf housing does not necessarily result in more disease unless management is suboptimal.

- Pair or group housing encourages solid feed intakes, resulting in higher growth rates.

- Appropriate weaning periods of ~14 days can help a smooth transition from high milk intakes onto solid feed.

- Checking temperature and humidity levels in calf housing can help identify if ventilation needs adjusting.

- Use your senses to check the quality of the housing environment — does it smell, is it damp, are there cobwebs and dust?