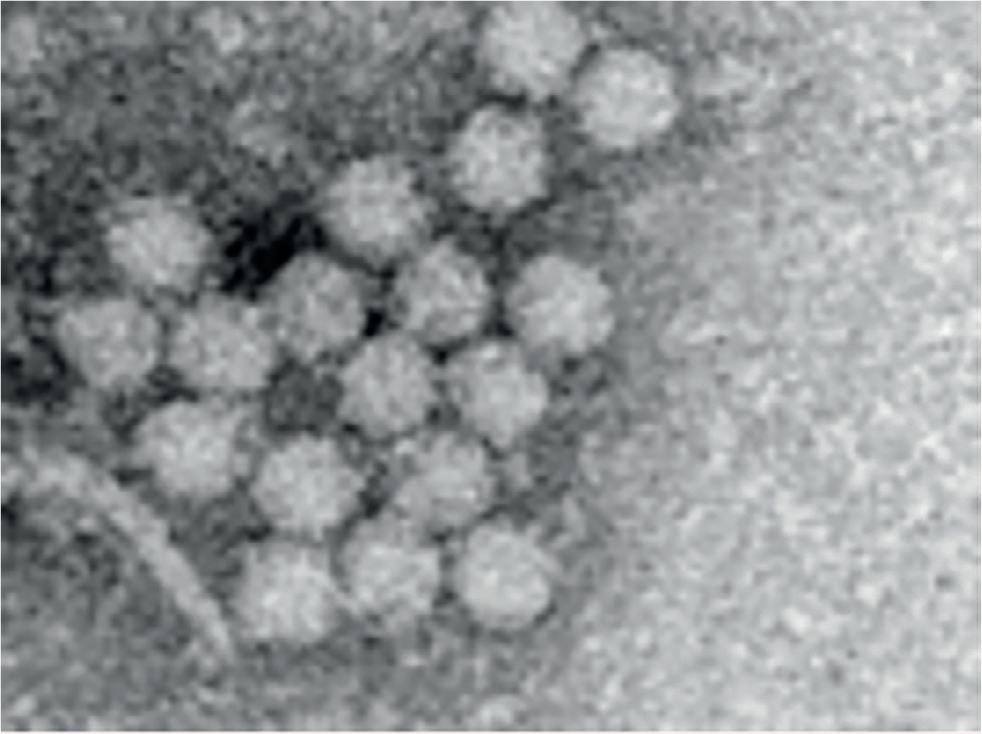

The porcine circoviruses belong in the family Circoviridae. There are two genera in this family Circovirus and Gyrovirus (chicken anaemia virus). Currently three types of porcine circoviruses have been described. The Circoviridae are non-enveloped small (12–23 nm in diameter) DNA viruses with an icosahedral symmetry (Figure 1). The single stranded DNA is arranged in a circular covalently closed loop (Zimmerman et al, 2019). The nucleotides are 1768 for porcine circovirus 1 (PCV1), about 1760 for porcine circovirus 2 (PCV2) and 2000 for porcine circovirus 3 (PCV3) (Zimmerman et al, 2019). All these viruses have been recognised from the 1960s in tissue samples and are almost certainly much older. PCV2 shares about 60% sequence identity to PCV1 (Zimmerman et al, 2019). PCV3 shares 50% sequence identity to PCV1 and 2. The Circoviridae are common viruses in vertebrates. There is no known zoonotic condition associated with porcine circoviruses. The structure of circoviruses makes them very resistant viral particles; without an envelope, lipid dissolving disinfectants (used against COVID-19) are ineffective. Virus inactivation requires alkaline disinfectants, oxidising agents or quaternary ammonium compounds.

Porcine circovirus 1

PCV1 was recognised as a contaminant of porcine kidney cell lines (PK-15) in the 1970s. A range of common conditions was initially wrongly attributed to PCV1, e.g. stillbirths, mummified piglets, congenital tremor, splay-leg and various vices — a common event with ‘newly discovered’ viruses. All these links have been progressively dismissed and PCV1 is currently not recognised as the causal agent of any pathological condition. It is ubiquitous, occurring on all pig farms and probably on all pigs around the world from Australia to Zambia (Zimmerman et al, 2019).

Porcine circovirus 2

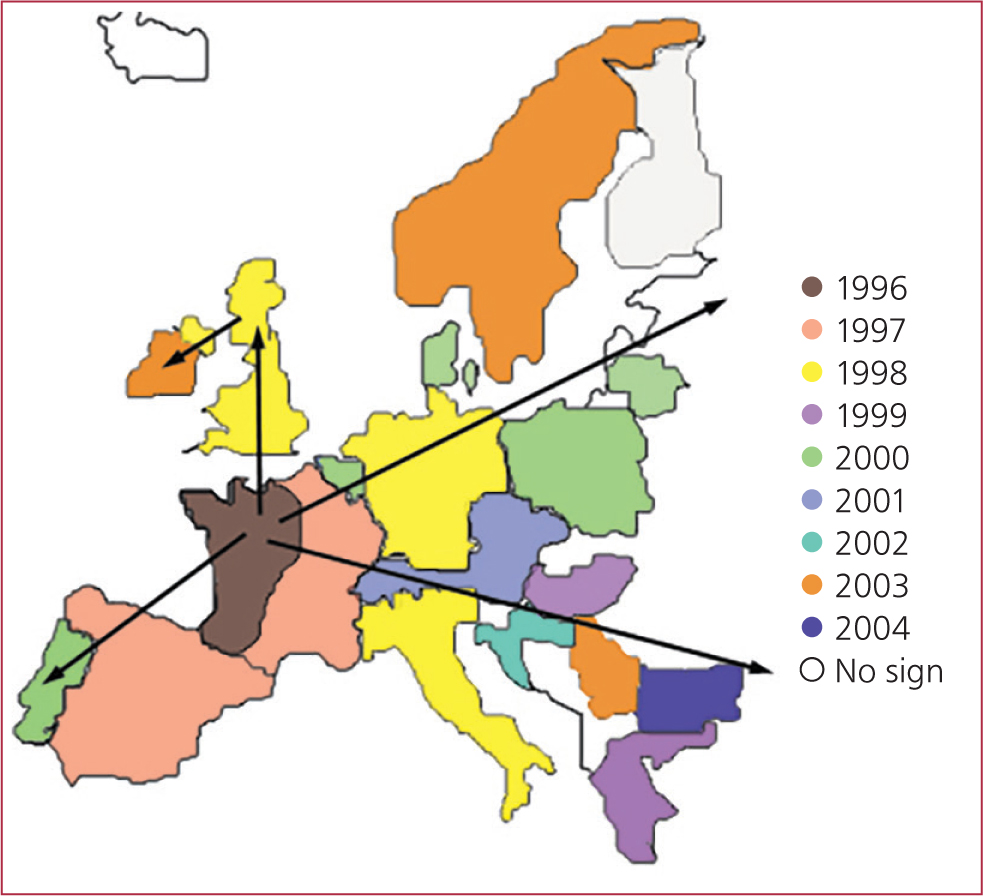

In 1994 a serious condition characterised by high mortality (>30%) in growing pigs and sudden wasting was recognised in France. This condition rapidly spread from France through Northern Europe (Figure 2) and then by exports to Asia over the next decade. The condition eventually reached North America in 2004 starting in Ontario and Quebec.

Simultaneously, a condition was recognised in Canada in 1991 (Harding and Clark, 1997) associated with 10% post-weaning mortality, jaundice and wasting where an intracytoplasmic basophilic body was seen in the histological tissues. The histology was similar to the condition young pigeon disease syndrome (PiCV). Examination of the Canadian samples revealed the virus PCV2, and the condition was dubbed porcine multisystemic wasting syndrome (PMWS) (Harding and Clark, 1997).

The same virus and intracytoplasmic inclusion bodies were found in the condition in Europe. Canada and European presentations were considered to be of the same origin but with different clinical presentations. In 2004/5, an emergency license was granted for the use of inactivated PCV2 vaccines in North America to curtail the spreading high mortality associated with PCV2 (Figure 3). Vaccination was an enormous success and despite the fact it is still not fully understood how it works, it has proved to be one of the most efficacious vaccines introduced into the global pig industry as it effectively stopped clinical PMWS in its tracks.

PCV2 had previously been a ubiquitous virus found in tissues from the 1960s without any known associated pathological condition. The virus can be found on all farms and when it is not isolated, the sensitivity of the test should be questioned.

It is normal to have 103 to 106 virus particles of PCV2 per ml of blood in healthy pigs (Carasova et al, 2006), and this means that in a 100 kg pig with 6 litres of blood there can be 6000 million virus particles in the blood stream alone.

All in a name

PMWS was deemed to be an unsuitable name because chronic wasting syndrome (of Elk) was associated with a prion disease and at that time bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) (also caused by a prion) carried an immense stigma. It was agreed to rename the condition porcine circovirus-associated disease (American Association of Swine Veterinarians (AASV), 2006). The fact that it is ubiquitous means that almost all pigs are ‘infected’ with PCV2, and therefore almost all diseases and syndromes can be found associated with PCV2; fulfilling Koch's postulates (the four criteria that determines whether a microorganism causes a disease) is more difficult.

Clinical presentation

The most well-known clinical expression of porcine circovirus systemic disease (PCV2-SD) is wasting or growth retardation (Figure 4), which may be accompanied by different degrees of skin paleness, respiratory distress (and pulmonary oedema; Figure 5), diarrhoea, icterus and increased mortality (Carr et al, 2008). In the early phase, an increase in the size of lymph nodes can be seen, but, not all apparently enlarged nodes are caused by the virus in affected individuals; the superficial inguinal lymph nodes may appear to be enlarged, when cachexia leads to a loss of fat covering (Carr et al, 2018) (Figure 6). In fact, the lymph nodes may be more obvious and appear larger, when they are actually smaller than normal.

Chronically affected pigs, that survive the acute phase, tend to develop cachexia (Carr et al, 2018). Since PCV2-SD affected pigs are immunosuppressed, they are very likely to suffer from concomitant pathogens, and additional clinical signs caused by these concurrent conditions can confuse the overall picture.

PCV2 may also contribute to SMEDI (stillborn, mummified, embryonic death and infertility), and PCV2 has been the sole pathogen found in late-term abortions and premature farrowing in some instances (Carr et al, 2018). This may be associated with fetal myocarditis and tends to be most severe in newly established herds with poor herd immunity and acclimatisation programmes (Carr et al, 2018). On most farms the impact of PCV2 on the reproductive performance is negligible.

Diagnosis

A herd diagnosis of PCV2-SD associated disease can be established based on two major criteria: significant increases in the percentage of wasted pigs and mortality compared with previous records and fulfilment of individual diagnostic criteria in three to five necropsied pigs. It is a herd diagnosis, it is not an individual animal diagnosis, and the identification of PCV2 on test polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and antibody concentrations (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)) are not diagnostic.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis requires:

- Clinical signs compatible with the condition

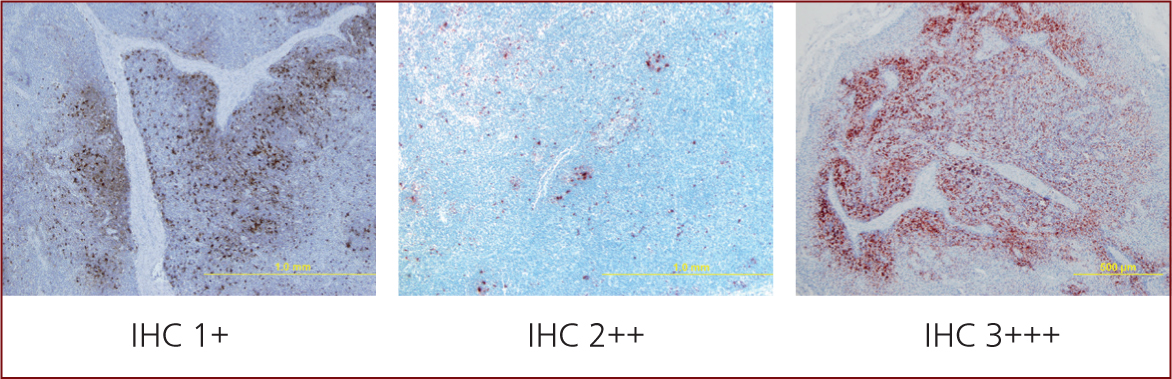

- Histopathological confirmation of moderate to severe lymphocyte depletion and granulomatous inflammation of lymphoid tissues

- Moderate or high amount of PCV2 genome or antigen in these lymphoid lesions (Figure 7), and demonstration by qPCR in blood of a cycle time of less than 20 (~107) in sera or 18 (~109) in tissues (Carr et al, 2018).

Note: Any draining lymph node from an infectious nidus is going to be enlarged. In cases of PCV2-SD the problem is systemic not local.

Management

PCV2-SD is considered a multifactorial disease in which management, concurrent infections, host genetics, nutrition and the timing of PCV2 challenge all play major roles. Multi-facetted approaches were deployed before vaccines were available in an attempt to ameliorate the impact of the disease, e.g. Madec's 20 point plan (Madec, 2001). Vaccination very quickly became the standard approach to PCV2 control and piglet vaccination around weaning remains an extremely common practice. Nevertheless, an adequate acclimatisation programme is strongly advised.

PCV2 was initially blamed for congenital tremor, splay-leg and various vices, but these claims have never been substantiated. Its role in SMEDI cases is limited in normal healthy vaccinated farms (Carr personal observation).

Evolution

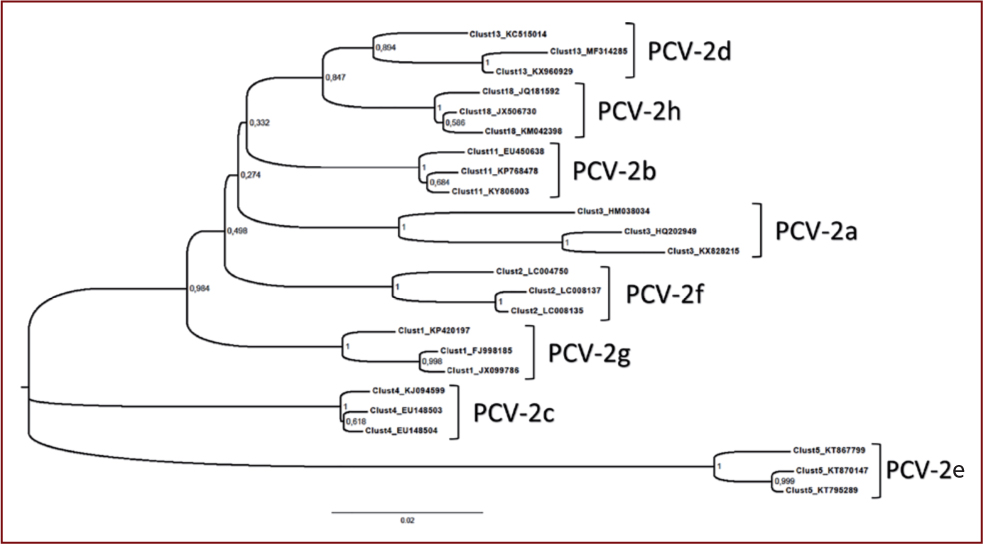

The initial belief that the PCV2 DNA was highly conserved has been discredited. Currently eight genotypes of PCV2 (a-h) are known to have been discovered (Franzo and Segalés, 2018) (Figure 8), which all appear to cause, or be associated with, similar pathologies. PCV2d is currently the most prevalent genotype.

A man-made chimera PCV1/2 which escaped from vaccine containment also circulates in Canadian herds (Gagnon et al, 2010).

Despite the evolving landscape, PCV2 vaccines based on PCV2a appear to remain highly effective (Carr personal observation).

Porcine circovirus 3

PCV3 has been characterised and retrospective analysis of tissues has demonstrated this virus in tissues in Brazil from the 1960s (Rodrigues, 2020). It is found in Sus scrofa, domestic and wild boar pigs, throughout the world.

PCV3 has been associated with stillborn and mummified pig-lets, congenital tremor, splay-leg and various vices, but the association with congenital tremor, splay-leg and various vices has been dropped.

There is, a growing body of evidence that this virus may well play a role in the SMEDI syndrome (Carr, 2018)

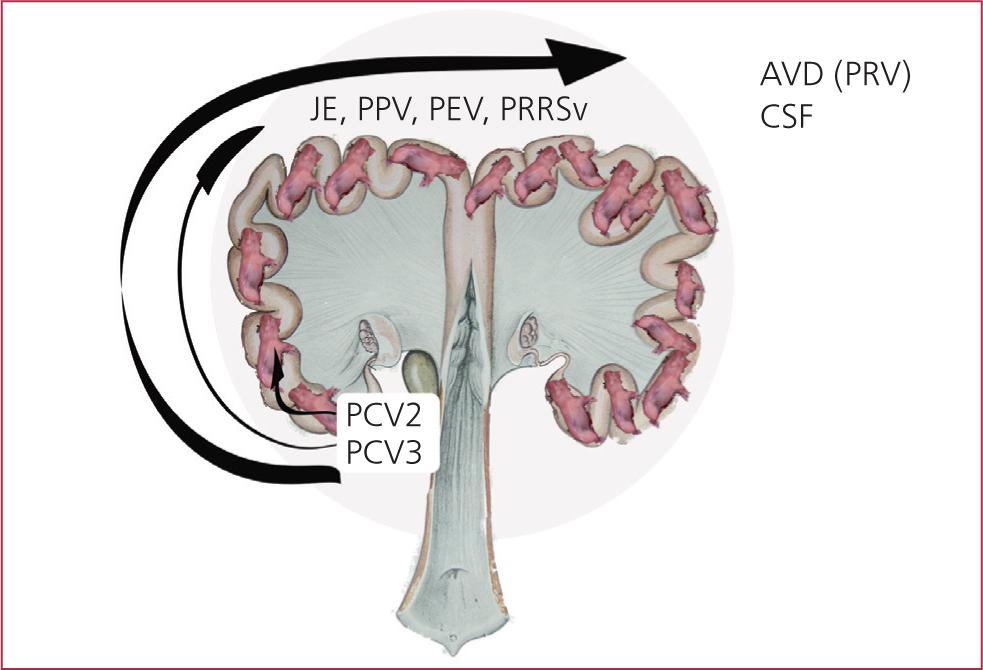

Other agents, e.g. techen viruses (enterovirus), Aujeszky's Disease, Japanese encephalitis virus and porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome have been shown to play a role in SMEDI conditions (Figure 9 and 10).

SMEDI must be managed as part of the gilt's acclimatisation programme.

Porcine circovirus 4+

PCV4 has yet to be recognised or characterised but almost certainly exists and will no doubt be heralded as the causal agent responsible for stillborns, mummified piglets, congenital tremor, splay-leg and various vices.

Porcine dermatitis and nephropathy syndrome

Porcine dermatitis and nephropathy syndrome (PDNS) is characterised by red-to-black erythema, haemorrhage and necrosis of the skin, usually with circular or irregular shapes (Muirhead and Alexander, 2013). Areas of predilection are the hindlimbs and perineal area (Figure 11). In some cases, skin lesions are generalised.

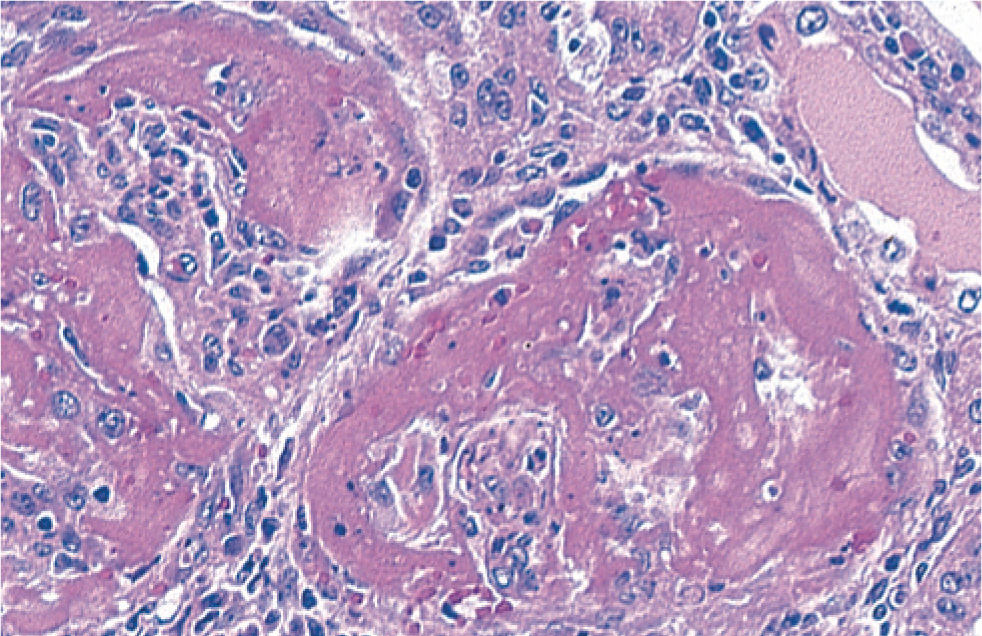

Histological examination of the enlarged kidneys reveals glomerular nephritis (Figure 12).

The causal agent responsible for PDNS has not been determined, although on farms with PCV2-SD, cases of PDNS are more common. PDNS should be considered as a symptom rather than specific condition.

The authors have examined many cases of PDNS in which PCV2 is notable by its absence by immunohistochemistry in pathologically abnormal or normal tissues from affected animals.

In PCV2 vaccinated herds, the incidence of PDNS may be used as a valuable marker for improper or failed vaccination, and this should be discussed with the farm health team.

It must be remembered that PDNS looks more like classical swine fever than classical swine fever. And, with African swine fever (ASF) on our borders it is vital to check any PDNS cases carefully. If the farm health team has any concerns the case might be ASF call it in to the local government officials.

Conclusion

Porcine circoviruses have become an integral part of the pig production landscape. They are an evolving pathogen whose impact spans from non-pathogenic to association with some of the most serious and far-reaching pathological conditions of pigs.

KEY POINTS

- Porcine circoviruses are common viruses and present in all pig farms around the world.

- Porcine circovirus 2 (PCV2) is associated with a serious wasting and mortality syndrome of growing pigs called porcine circovirus systemic disease (PCV-SD).

- The diagnosis of clinical PCV-SD is a herd diagnosis and requires clinical and pathological signs in three out of five examined pigs.

- The PCV2a vaccine is highly effective at controlling PCV-SD associated with all known variants of PCV2.

- Porcine circovirus 1 (PCV1) is a non-pathogenic virus.

- Porcine circovirus 3 (PCV3) appears to be associated with the common stillborn, mummified, embryonic death and infertility (SMEDI) syndrome of pigs.

- Porcine dermatitis and nephropathy syndrome (PDNS) is as yet not ascribed to a particular PCV as the causal agent.