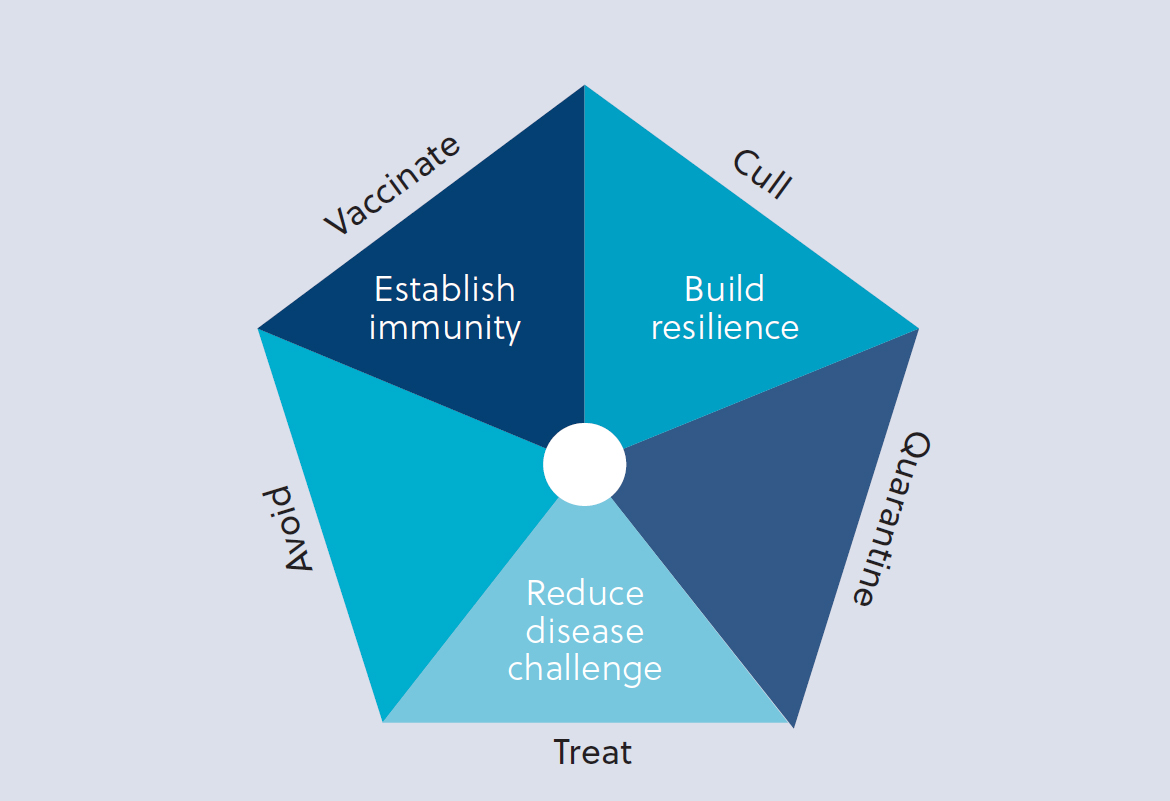

Vaccination is an integral part of progressive preventative flock health management. It sits within a toolbox of measures, which include good biosecurity and nutrition, to effectively prevent or control disease on farm. NOAH (the National Office of Animal Health) has produced a livestock vaccination guideline to support vets, Suitably Qualified Persons (SQPs)/Registered Animal Medicines Advisors (RAMAs) and farmers to make informed decisions on vaccination use and manage the health and welfare of sheep (NOAH, 2022).

Motivation to vaccinate

The decision to vaccinate sheep is primarily motivated by animal welfare and the wish to optimise health by giving sheep the best chance to be free from avoidable disease. If optimum protection from all disease were the only driver, then there would be no need for debate as to which diseases to vaccinate against, or the level of risk required to motivate vaccination. However, most sheep flocks are kept as commercial ventures that need to be economically sustainable. There is a balance to be struck between optimum flock welfare, performance and productivity. In most cases there is no conflict between the three and almost always a compromise in welfare occurs to the detriment of both performance and productivity. However, to maintain the economic viability of a flock, it is important to carefully consider the cost–benefits of vaccinations and strategies over a sufficiently long period of time.

In the short term, an unvaccinated flock might be ‘lucky’ and ‘get away’ without the protection of vaccination. However, as prey animals that are often kept extensively, there may be limited opportunities for shepherds to quickly identify and diagnose individual sheep that are clinically ill. Once identification of the individual and appropriate action has been taken, there is a high chance that the disease will have already spread to other sheep in the flock. For these reasons, vaccination is a key tool within the ‘Plan, Prevent, Protect' ethos to enable flock owners to protect their animals and to reduce the spread of disease (Lovatt et al, 2019). Indeed flock owners that vaccinate ewes against clostridial and abortion diseases have been shown to have higher flock productivity than those that do not (Lima et al, 2019). Table 1 summarises important UK sheep diseases that can be vaccinated against.

Table 1. Diseases that can be vaccinated against in UK flocks (NOAH, 2022)

| Category one | Category two |

|---|---|

| Clostridial diseases | Orf |

| Lameness: footrot | Ovine Johne's disease |

| Abortion: toxoplasmosis | Mastitis caused by Staphylococcu aureus |

| Abortion: enzootic abortion of ewes, Chlamydia abortus | Arboviruses as required |

| Pasteurellosis: Pasteurella (Mannheimia haemolytica and Bibersteinia trehalosi) |

The NOAH vaccination guideline introduces the concept of two categories of vaccination to support flock health planning (Table 1) (NOAH, 2022). Diseases which fall under category one vaccinations are considered to be ‘core’ as they potentially pose a threat to every sheep flock in the UK. These vaccinations should be considered as the foundation of a standard vaccination programme. That is not to say that every sheep in every flock should receive every category one vaccine, although arguably this should be the default situation for flocks that are not actively flock health planning alongside veterinary support. Through the flock health planning process, every flock owner should have carefully considered every group of sheep and provided justification for reasons where they are not give a category one vaccination – thus switching the mindset for decision making from ‘why vaccinate?’ to ‘why not vaccinate?’ for these vaccines. Clear suggestions for specific decisions with respect to whether to vaccinate specific categories of sheep in each flock is given in the table in the Livestock Vaccination Guidelines (NOAH, 2022).

Category two vaccinations are against diseases for which the level of threat to flock health and welfare will vary on an individual farm basis. Decisions on the appropriateness of using all vaccinations are for the vet to assess based on the health status of a flock, sheep welfare, flock productivity and the cost–benefits of vaccinating against each disease.

Vaccination strategies for UK flocks Category one vaccinations

Clostridial diseases

Numerous studies have identified key clostridial pathogenic species, as either vegetative cells or endospores, in most farm soils (Palmer et al, 2019). Indeed, the widespread abundance of clostridial pathogens in soil represents a key route of infection for susceptible grazing animals, such as sheep. Commonly, clostridial diseases in sheep present as sudden death (Lovatt et al, 2014) with a range of diseases that include enterotoxaemias (Otter and Uzal, 2020a) such as lamb dysentery or ‘pulpy kidney’, other alimentary tract infections, such as those caused by Paeniclostridium sordellii as well as tissue damage diseases such as ‘blackleg’ and ‘black disease’ and neurotoxic diseases, such as botulism and tetanus (Otter and Uzal, 2020b).

Pulpy kidney (Clostridium perfringens D) was the third most common cause of lamb death found in 2733 lamb carcasses examined by Farm Post Mortems Ltd over a five year period up to 2019. Pulpy kidney and lamb dysentery (C. perfringens B) were both in the top seven most common diagnoses in young lambs up to 7 days old submitted to the Animal and Plant Health Agency over the same time period (Sheep Health and Welfare Group, 2021).

Clostridial disease is often precipitated by a trigger factor, such as change in management, or traumatic or parasitic damage to tissues (Aitken, 2008), so good flock management and feeding practices are considered important factors in the control of clostridial disease (Otter and Uzal, 2020b). However, the ubiquitous nature of the causative bacteria, resulting in a wide range of common sheep diseases, alongside the ready availability of effective vaccines, means that flock control by vaccination is widely considered as best practice (Henderson, 2002; Lovatt, 2004; Lewis, 2011; Scott, 2015).

The uptake of clostridial vaccinations has been fairly steady over the last 10 years with a penetration of 65% in 2022 (assuming that all ewes and rams should receive an annual booster and that all lambs on farm in June should receive two doses) (Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB), 2022).

Lameness

Lameness is a significant issue on UK farms with surveys suggesting that over 3% of ewes are lame at any one time, with footrot and contagious ovine digital dermatitis (CODD) as predominant causes of lameness (Winter and Green, 2017; Prosser et al, 2019; Best et al, 2020). Footrot alone costs individual farmers an average of £3.60 per ewe on a farm with >10% lameness costing up to £6.35 (Winter and Green, 2017), or even as much as £14 (Lovatt, 2014), per ewe, in the flock per year. Footrot vaccination has been associated with a reduction in prevalence of lameness of between 20 and 70% (Prosser et al, 2019), with some efficacy against both footrot and CODD in co-infections.

In the AHDB Vaccine Report (AHDB, 2022), levels of penetration rose steadily from 11% in 2012 to 19% in 2021, although they fell to 16% in 2022, presumably as a result of significant vaccine supply and availability issues. Here it was assumed that all ewes intended for first time breeding and all rams should receive two doses of vaccine and all other ewes receive a single dose. In the practical and clinical control of lameness on farm, there is good anecdotal evidence of the usefulness of vaccination. However, sheep farmers tend to consider vaccination as a reactive tool and non-vaccinating farmers will not put it in place until their lameness levels reach a prevalence as high as 19% on average (Best et al, 2020). Evidence suggests that lameness prevalence is only lower in flocks that have been vaccinating for over 5 years and it should be considered a long-term preventative measure rather than a short-term reactive one (Prosser at al, 2019; Best et al, 2020). Vaccination is considered a key component of the Five Point Plan for lameness control, which was launched by the sheep industry in 2014 (Figure 1).

There are considerable resources concerning lameness control for both vets and farmers collated at the free to access Healthy Feet Happy Sheep website (https://bit.ly/healthyfeethappysheep).

Abortion

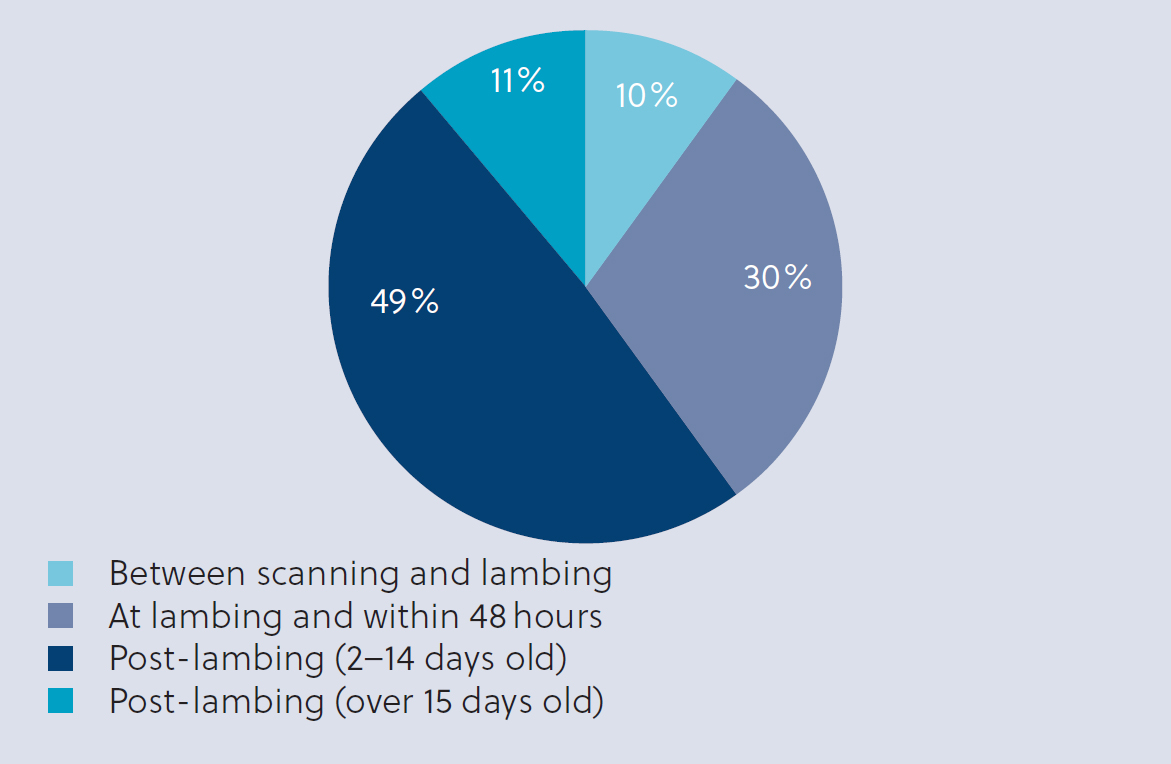

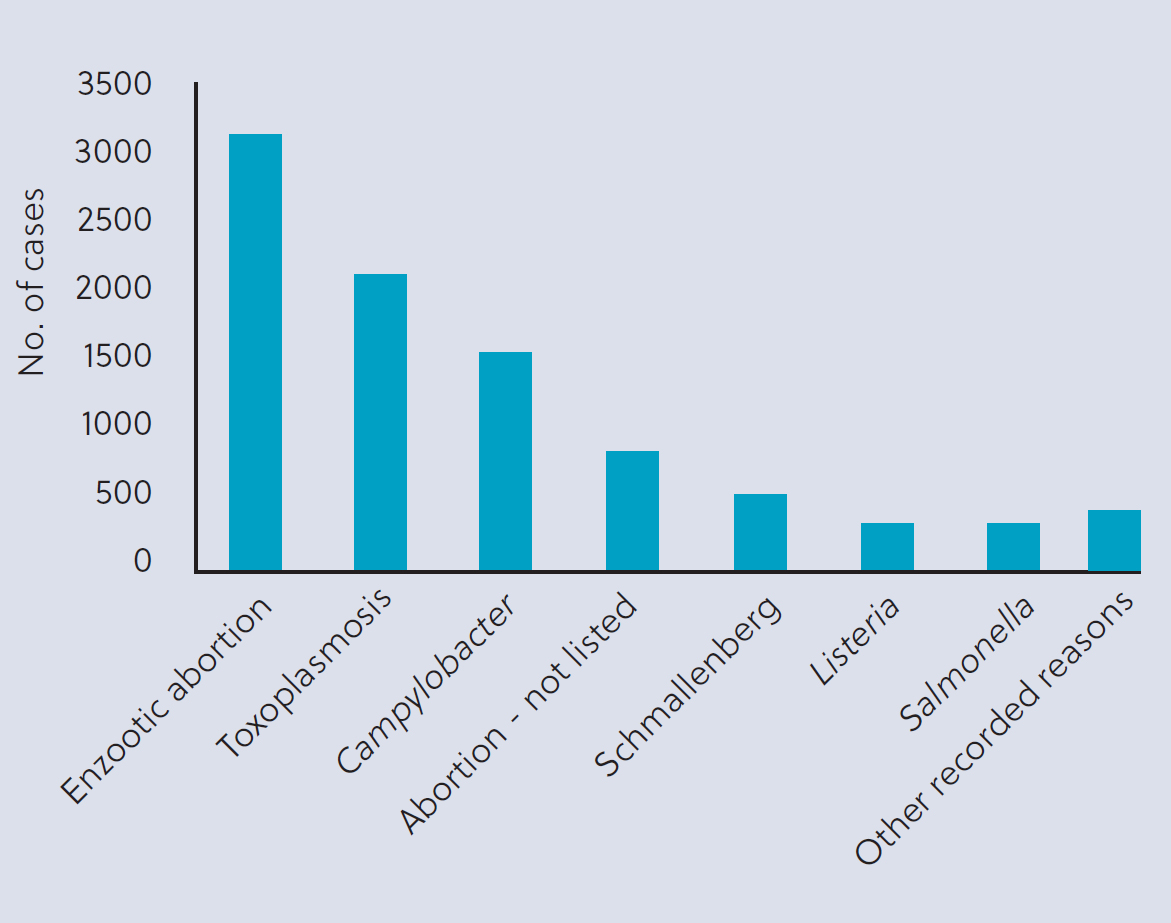

Approximately one-third of all lamb losses have been shown to occur between scanning and lambing and so could be attributed to abortion (Figure 2). Figure 3 illustrates the diagnoses of GB sheep abortion/fetopathy from 2012–2023 (APHA, 2023). For every year since 2012, enzootic abortion of ewes (EAE) has been the top diagnosed cause, although the picture did change in 2023 when the highest two reasons were Campylobacter (165 cases) and toxoplasmosis (163 cases) compared to EAE at 144 cases nationally. An unpublished study in 2014 indicated that 81% of 500 GB flocks had been exposed to Toxoplasma gondii, 52% to EAE and 43% to both organisms (MSD, unpublished data). Funded by a commercial company, private veterinary surgeons collected up to eight samples from each flock, taken from primarily barren or aborted ewes.

Abortion vaccine uptake increased from a low of 22% penetration of toxoplasma vaccine and 33% penetration of EAE vaccine in 2013 to 31% and 50% respectively in 2021 (considering first-time breeding ewes as the denominator). However, again presumably as a result of supply and availability issues, penetration rates decreased to 20% toxoplasma vaccine and 44% EAE vaccine in 2022 (AHDB, 2022).

Investigation of UK flocks that had had EAE over 4 or more years demonstrated that failure to vaccinate was a consistent feature (Carson et al, 2019). Given the potential for widespread economic losses as a result of EAE (Robertson et al, 2018), all flocks that are bringing in replacements should be vaccinating replacements for EAE, including those that are sourcing replacements from EAE accredited flocks (Crilly et al, 2021). Vaccination need not be considered essential in flocks that do not bring in replacement ewes or have other sheep flocks as direct neighbours and who have diligent biosecurity and proactive investigation of all cases of abortion (Crilly et al, 2021). However, it is always worth considering the zoonotic risk posed by EAE and the need to vaccinate from a One Health perspective for individual flocks (NOAH, 2023).

Pasteurellosis

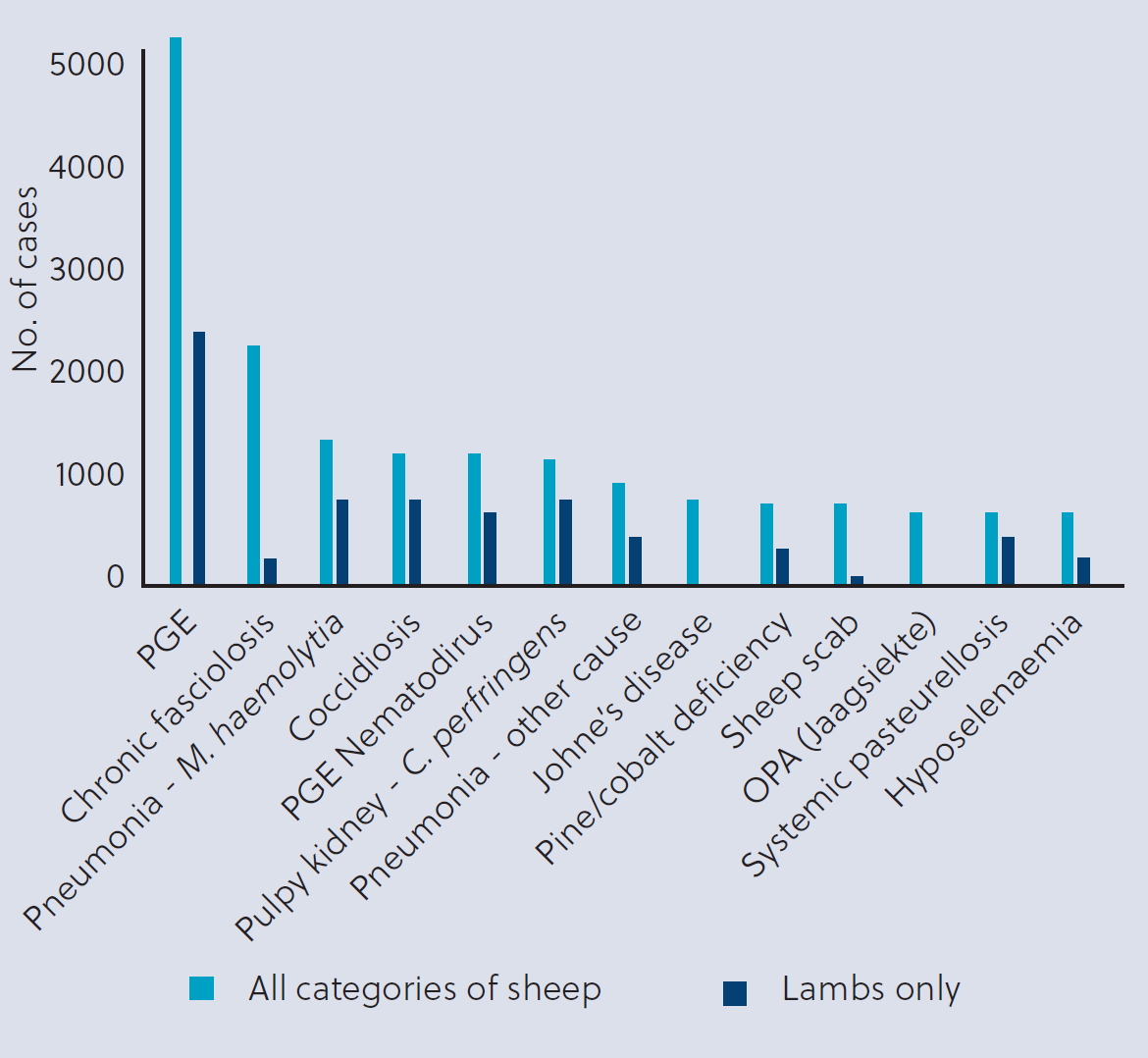

Pasteurellosis is the most commonly diagnosed cause of death in UK lambs. Out of the 2733 lamb carcasses submitted to Farm Post Mortems Ltd via a fallen stock centre, 11% were diagnosed with Pasteurella septicaemia and over 4% with Pasteurella pneumonia in the 5-year period up to 2019 (Sheep Health and Welfare Group, 2021). Pasteurellosis accounted for just over 2% of ewe deaths (out of 1815 ewe carcasses submitted to Farm Post Mortems Ltd over five years up to 2019) (Sheep Health and Welfare Group, 2021) and significant numbers of cases recorded annually by the GB Sheep Disease Surveillance Dashboard (Figure 4) (APHA, 2023). The cost of bacterial pneumonia has been shown to be a significant percentage of the value of lamb in Europe (6–7% of lamb value) and in New Zealand (1.36 NZD per lamb) (Lacasta et al, 2015). Cases usually occur a month after housing, when lambs are moved to richer pasture in late summer, or as a result of stress following handling, extreme weather or other respiratory pathogens (Bell, 2008).

The frequency of infection and potential for significant economic losses in the face of disease mean that vaccination against pasteurellosis is considered best practice for all UK sheep flocks. It is recommended that lambs should be vaccinated at least 2–3 weeks before the period of maximum risk (González et al, 2019). The available UK vaccine is authorised from 3 weeks old, with a second dose 4–6 weeks later and supplementary boosters suggested within 3 weeks of expected seasonal outbreaks, which occur in autumn in the UK. Table 2 highlights key details on vaccinating against pasteurellosis.

Table 2. Pasteurellosis vaccination (NOAH, 2022)

| Vaccination details | Class of sheep to vaccinate | Veterinary discussions specific to flock circumstances |

|---|---|---|

| Delivery alongside appropriate clostridial vaccine or as separate Pasteurella vaccine |

|

|

|

|

The uptake of Pasteurella vaccinations has been gradually increasing over the last 10 years, with a penetration of 52% in 2022 (assuming that all ewes and rams should receive an annual booster and all lambs on farm in June should receive two doses) (AHDB, 2022).

Category two vaccinations

Orf

Orf, a Parapoxvirus that is also described as ovine ecthyma, scabby mouth or contagious pustular dermatitis, is highly contagious and widespread. Prevalence rates in England have been calculated as 1.9% for ewes and 19.5% for lambs (Onyango et al, 2014) with associated high costs resulting in a loss of profit margin of between £1.06 and £7.92 per ewe in flocks that experience outbreaks of orf (Lovatt et al, 2012).

Vaccination is only recommended in flocks where there is already orf disease present. Two separate surveys, one with 762 English sheep farmers in 2012 (Lovatt et al, 2012) and another with 570 UK sheep farmers in 2018 (Small et al, 2019), suggested that 36% of respondents used the orf vaccine. However, market penetration of the orf vaccine is estimated at 16% (2% of ewes and 13% lambs) (Small et al, 2019). Of the farmers who did not vaccinate, 63% reported that there was no justifiable need to vaccinate, including no orf present on their farm (Small et al, 2019). It has been suggested that orf is present on 25% of UK farms and evidence suggests clear welfare and cost benefits to the use of vaccination, specifically of all lambs born on these farms and, ideally, also in the ewes (Onyango et al, 2014).

Ovine Johne's disease

Johne's disease (paratuberculosis) is an infectious chronic wasting disease caused by Mycobacterium avium subspecies paratuberculosis (MAP). With a worldwide distribution, it is commonly recognised as having significant production-limiting effects on multiple species. There is currently a lack of published information as to the prevalence of ovine Johne's disease (OJD) in the UK, and an absence of good data, although one survey of 50 large commercial UK flocks indicated a farm level prevalence of 64% based on faecal polymerase chain reaction and post-mortems of cull ewes (Robinson et al, 2019). Recent UK industry publications (Windsor, 2006; Sheep Health and Welfare Group, 2021) have suggested that OJD is of high significance both in terms of prevalence and economic impact at flock level, with one study suggesting that only 17% of lowland breeding ewes are retained for more than 3 years in flocks infected with OJD compared with 40% in uninfected flocks (Robinson et al, 2019).

Vaccination has been shown to reduce the onset of disease, incidence of mortality and faecal shedding of MAP all by approximately 90% in Australia (Windsor, 2006). A meta-analysis of 49 sheep studies across the world showed positive effects of vaccination in terms of production, epidemiological and pathogenetic effects on flocks (Bastida and Juste, 2011). Good UK flock data are limited but there is good evidence to suggest that flocks that produce breeding sheep should be routinely undertaking post mortem examinations of fallen stock and screening older ewes to test pooled faecal samples for MAP by polymerase chain reaction. There is a strong argument to suggest that breeding sheep that are born into a flock with OJD-positive ewes should be vaccinated by 4 months old. Reasons not to vaccinate may include aspirations to export sheep or concerns that vaccinates cannot be differentiated from naturally exposed animals on serology.

Other sheep diseases

Other sheep diseases for which there are UK vaccines available include mastitis caused by Staphylococcus aureus and abortion caused by Salmonella abortusovis, although this is not currently detected in the UK. Vaccines for Campylobacter fetus and caseous lymphadenitis are imported under a special import licence by vets for use in their clients' flocks but neither are currently specifically authorised for use in the UK.

Arbovirus is an informal name for any virus that is transmitted by arthropod vectors. They are likely to become a greater threat associated with climate change. Vaccines are intermittently available in the UK following initial incursion from continental Europe since 2007. Examples include Bluetongue virus (BTV)-8 and Schmallenberg virus. The current outbreak of BTV3 in the Netherlands poses significant risk to UK flocks so that it is almost inevitable that we will face BTV3 transmission via UK midges by summer 2024; however, there is currently no specific BTV3 vaccine available globally (Ruminant Health and Welfare Group, 2022). The cases currently being found in the UK are not evidence of circulating virus.

Practical considerations for vaccination safety

It is important that veterinary prescribers ensure that clients are advised how to use vaccines with care and in accordance with datasheet recommendations and indeed recent work has highlighted vaccination site errors as well as numerous examples of poor storage conditions on farm (Hall et al, 2022). Care with administration is particularly important in the administration of the oil-based vaccines such as those against footrot and Johne's. There have been multiple reports of progressive paralysis (Windsor and Eppleston, 2006; Strugnell et al, 2018; SRUC, 2022) following misadministration of these vaccines into the cervical musculature instead of subcutaneously. The outcome from work in Australia (Zoetis, 2016; Zoetis, 2017) suggests that a quarter-inch needle should be used at a 45° angle for lambs or thin ewes and at a 90° angle for fit sheep with wool cover to avoid inadvertently deep administration.

Conclusions

Vaccination is a key tool for the protection of the flock and the prevention of disease in sheep. To preserve high standards of sheep welfare and flock performance and productivity, every flock owner should be considering category one vaccines by default and working through risk assessments with their vet to justify not using them in certain circumstances. Clinical evidence and diagnostic screening will indicate whether orf or OJD vaccines are required to minimise the impact of either disease in the flock. The NOAH Livestock Vaccination Guideline is available to provide further insights into vaccination programmes for sheep, and beef and dairy cattle. LS

KEY POINTS

- Vaccination is a key tool in the box of preventative flock health measures.

- For category one vaccinations, there should be clear rationale given in the flock health plan to justify why a flock is not fully vaccinated.

- Category one vaccines for sheep include those against clostridial diseases, pasteurellosis, footrot, toxoplasmosis and enzootic abortion.

- A table of clear practical guidelines for vaccination of different categories of sheep can be found in the NOAH guidelines on pages 41–43.