Abscessation of the bovine reproductive tract is rare and usually diagnosed by transrectal ultrasound or post-mortem examination (Peavey et al, 2001). Mee et al (2009) found abscessation or adhesion of any part of the reproductive tract in just 1.2% of 7797 ultrasound examinations in 5751 Holstein-Friesian cattle, while Al-Dhash and David (1977) found no ovarian abscesses in 8071 bovine reproductive tracts examined at slaughter. Ovarian abscesses in cattle are thought to arise secondary to bacterial infection of the uterus (Zulu et al, 2000).

This case report discusses the surgical treatment of a 28-month-old first lactation dairy cow with a right ovarian mass, alongside the further investigations performed to reach a conclusive diagnosis of ovarian abscessation and oophoritis.

History

A first lactation, 28-month-old Holstein dairy cow was presented at a routine fertility visit at 47 days in milk for ‘oestrus not observed’. The cow had been examined at a previous routine fertility visit and treated for a grade 2 metritis at 21 days post calving with intramus-cular amoxicillin (Betamox 150 mg/ml, Norbrook Laboratories), 7 mg/kg for 3 days.

A small left ovary with no palpable structures, and a firm mass on the right ovary were found on rectal examination, the mass was estimated to be 4 cm diameter on rectal palpation. The uterus was fully contracted and within normal limits on palpation. On ultrasound examination the left ovary was small with no active follicles, while the right ovary showed a number of small follicles with a large 3.5 cm hyperechoic structure with a hypoechoic central region that was presumed to be a corpus luteum. The structure on the right ovary was treated with 0.150 mg of d-cloprostenol (Prellim, Zoetis) to attempt luteolysis.

The cow was seen 2 weeks later and treated, with a second d-cloprostenol injection, with no response. The cow was monitored for 6 further weeks and displayed no signs of oestrus, while the mass on the right ovary continued to grow in size. Eight weeks after initial examination, the left ovary remained inactive and the right ovary had grown to an estimated 8 cm in diameter with a lobulated texture on palpation, appearing hyperechoic on ultrasound with a number of fluid filled chambers. The uterus remained small and without tone on rectal examination. The right ovary was located clear of the pelvic cavity within the abdomen.

Differential diagnosis

The mass on the right ovary was initially diagnosed as an enlarged persistent corpus luteum. However, as the mass was monitored over the ensuing weeks the differential diagnosis list was expanded to include several causes of ovarian enlargement (Meganck et al, 2011; Jackson et al, 2014):

- Cystic ovarian disease

- Ovarian tumour (likely granulosa cell tumour (GCT))

- Ovarian abscess

- Oophoritis.

Treatment

As a result of the size, persistence and ultrasonographic appearance of the right ovarian mass a working diagnosis of GCT or ovarian abscess was made and treatment options were discussed with the client:

- Surgical biopsy for a definitive diagnosis

- Exploratory laparotomy to confirm the diagnosis with or without unilateral ovariectomy

- Leave as not in calf and manage as a barren cow prior to culling from the herd.

Successful returns to cyclicity, and in some cases successful subsequent pregnancies, have been described following unilateral ovariectomy occasionally accompanied by partial hysterectomy (Dobson et al, 2013: Marchionatti et al, 2016). Little information was found on success rates of removal of ovarian abscesses, but with the rate of growth there was a concern of rupture that could lead to a fatal peritonitis, and so exploratory surgery with ovariectomy was planned.

Surgical procedure

A unilateral ovariectomy under local anaesthetic (inverted-L block (Weaver et al, 2018)) with a high right-sided incision to allow full exteriorisation of the right ovary, as described by Jackson et al (2014), was planned.

Prior to preparing for the unilateral ovariectomy, a final rectal examination of the cow was performed which found: no palpable structures on the left ovary, a small non-gravid uterus and the approximately 8 cm diameter mass with a lobulated texture on the right ovary sitting past the pelvis and free in the abdomen, located ventral to the level of the pelvic brim. No other abnormalities were detected on clinical examination.

Preoperatively, 8.75 mg/kg intramuscular amoxicillin clavulanate (Synulox Ready To Use Suspension For Injection, Zoetis) was administered alongside 0.5 mg/kg meloxicam (Meloxidyl, Ceva Animal Health) subcutaneously. An inverted L block of the right flank used 185 ml of procaine hydrochloride with adrenaline (Adrenacaine, Norbrook Laboratories). The site was surgically prepared and 0.1 ml/100 kg of 2% xylazine hydrochloride (Rompun 2%, Elanco) was administered intravenously for sedation.

The initial incision was made with the cow standing, on the right side — it measured approximately 15 cm in length and ran cranioventral from 2 cm cranial to the tuber coxae. Despite additional sedative and local anaesthetic adequate exteriorisation of the ovary was not possible with the cow in a standing position, and the surgery proceeded with the cow in left lateral recumbency on a clean straw bed. The cow was chemically restrained with a combination of xylazine hydrochloride and a high dose epidural. The incision site was extended to approximately 30 cm to aid visualisation.

The incision site and omentum were flushed with 300 ml of sterile 0.9% saline (Aqupharm 1, Animalcare Ltd) before recommencing surgery. With the patient in left lateral recumbency elevation of the ovarian mass was possible and blunt dissection through the omentum allowed clear visualisation. Similarly to the ovarian abscess described by Zulu et al (2000) adhesions were seen that required dissecting, in this case from the ovary to the omentum and large bowel.

On exteriorisation of the right ovary and after packing gauze swabs around the incision, a fluid filled structure ruptured producing approximately 30 ml of thick, creamy, purulent material. The right ovary, associated structures and abdomen was flushed with 0.9% saline.

The right ovarian pedicle was found to be enlarged at 2 cm in diameter (larger than that described in Jackson et al (2014)). This was ligated using proximal and distal transfixing ligatures (coated VICRYL (polyglactin 910) 2 metric) with surgeon's knots. An additional two encircling sutures were placed using Miller's knots in coated VICRYL as before. A branch of the ovarian artery lateral to the ovary, within the broad ligament, which was assumed to be supplying the growth, was also ligated. Allis tissue forceps were used to grasp the pedicle and the ovary was excised. After excision the pedicle was visualised for 60 seconds to ensure no haemorrhage before lowering into the abdomen. Full abdominal lavage was performed using warm, clean water. The musculature was closed in two layers in a simple continuous pattern using coated VICRYL, as before. No evidence of haemorrhage was detected during closure of the abdomen. The skin was closed in a ford interlocking pattern using nylon (Supramid, BBraun).

The patient was placed on a further 5-day course of intramuscular amoxicillin clavulanate and a second dose of subcutaneous meloxicam was given 3 days postoperatively.

The cow required additional supportive care but was ambulatory and defecating, urinating, drinking and eating normally 5 days postoperatively. However, the milk yield remained low and the cow was culled from the herd 8 days post-surgery.

Further investigations

Gross description

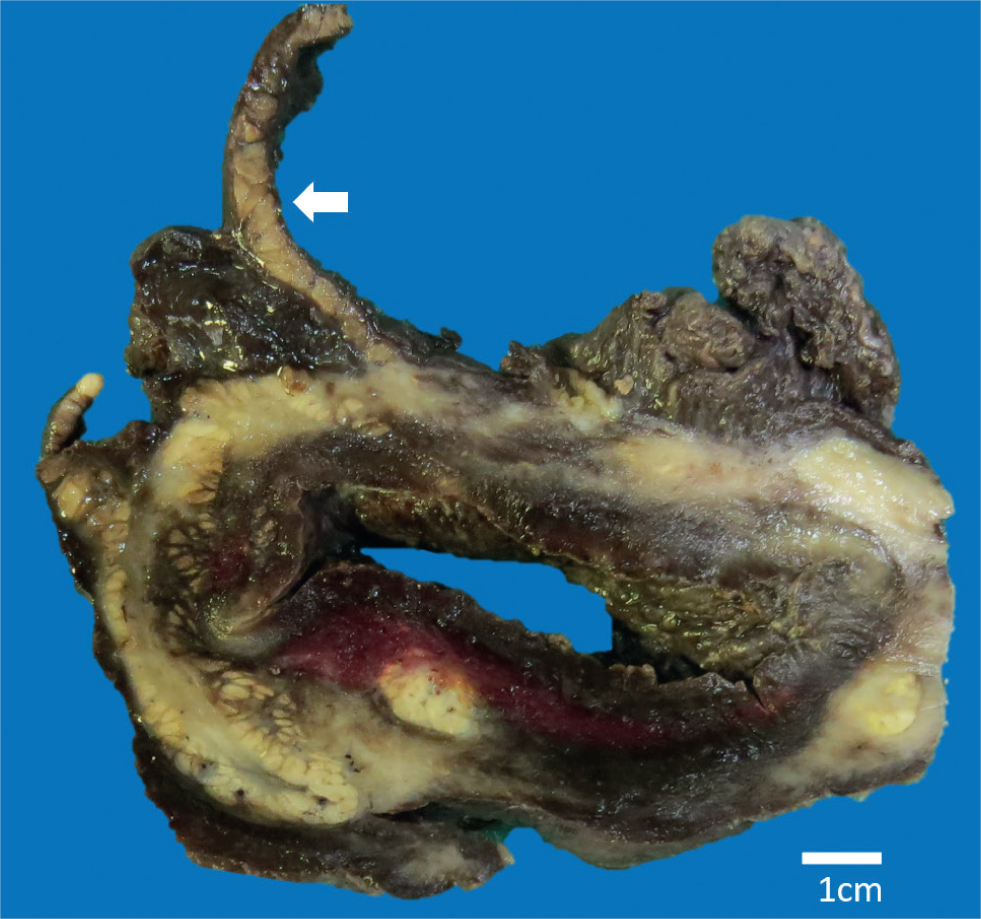

The mass was placed in 10% neutral buffered formalin for 72 hours. The fixed ovary measured 9 x 8.5 x 6 cm, weighed approximately 430 g and had adipose tissue attached along one edge. On cut surface a single large structure with a wall measuring approximately 2 cm and a central cavity measuring 0.5 x 5 cm at the widest point was seen (Figure 1).

Microscopic description

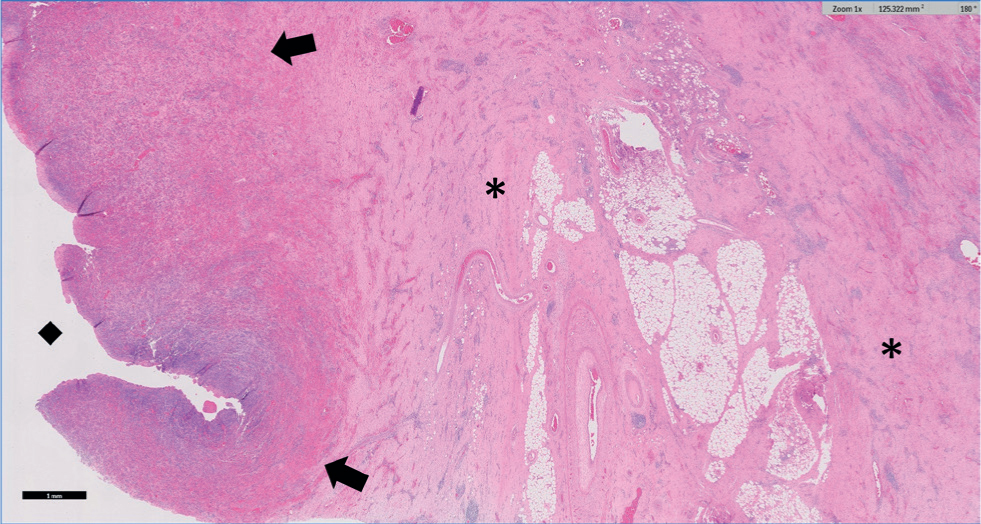

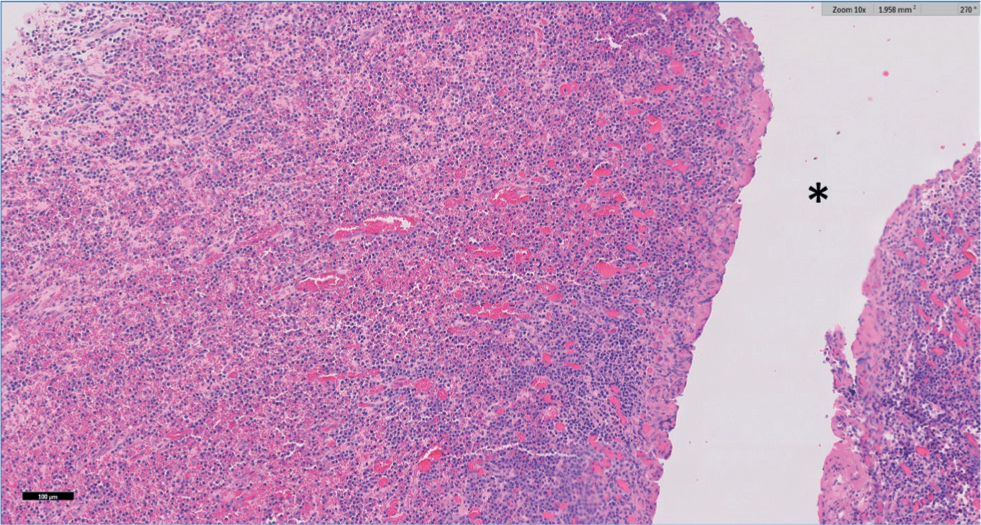

Tissues were routinely processed, embedded in paraffin wax and multiple 4 µm sections were stained with haematoxylin and eosin which were examined by two of the authors (KW and MW). On histopathology the ovarian tissue was nearly totally effaced by marked fibrosis extending into the surrounding adipose tissue, which shows multifocal fat necrosis. Surrounding the central cavity was a broad zone of markedly congested granulation tissue with multifocal haemorrhage and abundant plasma cells with smaller numbers of macrophages and lymphocytes (Figure 2 and 3). Occasional bacterial colonies were present within this tissue. Where serosa was evident it was expanded by moderate to marked haemorrhage with fibrosis. No fungal organisms or acid-fast bacilli were detected using Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS) and Ziehl-Neelsen (ZN) stains respectively. Changes on histopathology were consistent with a diagnosis of chronic-active oophoritis and cavitation (ovarian abscessation).

Discussion

The oophoritis seen in this case may have originated as a result of the grade 2 metritis that the cow was treated for at 21 days post-partum. Zulu et al (2000) described ascending infection from the uterus, for example from metritis, as the most likely cause of ovarian abscessation. Considering when the ovarian structure was first diagnosed, and the prior grade 2 metritis, there may well be a causal relationship in this case. Bacteriology of the intra-lesional fluid was not performed, however, it may have provided further information regarding the origin of the infection.

Exteriorisation of the ovary was extremely difficult and, when compared with other ovariectomy surgical reports, it is evident that the ease of exteriorisation is variable. Jackson et al (2014) and Marchionatti et al (2016) described unilateral ovariectomy, and hysterectomy respectively with apparent ease of exteriorisation. In contrast, Peavey et al (2001) and the cow in this case report, had less mobile ovaries which required greater dissection in order to achieve adequate exteriorisation of the ovary. It is likely that the significant adhesions (Peavey et al, 2001) that can occur between the reproductive tract and other abdominal structures inhibit adequate exteriorisation of the ovary until they are resected.

As the cow was culled before any further ultrasonographic examinations of the reproductive tract, it is not possible to draw conclusions on the prognosis for return to cyclicity of the cow. Ultrasonographic stills of the right ovary and associated mass are not available, however, the authors note how these would have added further educational value to this case report.

When reviewing the literature for evidence on return to cyclicity following unilateral ovariectomy, Hosteller et al (1997) achieved a successful return to cyclicity and a successful pregnancy. In contrast, neither of the heifers operated on by Meganck et al (2011) returned to cyclicity as one died postoperatively and one was culled from the herd. Peavey et al (2001) found an improvement in fertility after surgery to remove ovarian abscessation, provided the contralateral ovary was unaffected. There is little other evidence relating to the return to cyclicity in cattle after unilateral ovariectomy for ovarian abscessation. It is therefore important to be realistic with owners about the mixed prognosis for unilateral ovariectomy with respect to future pregnancies.

Conclusion

Ovarian abscesses are a rare cause of ‘oestrus not observed’ in cattle, however, they should still be considered on the differential list for these animals. Surgical management is a treatment option for these cases, and should be considered because of the risk of rupture, which may release purulent material in the abdomen resulting in a subsequent peritonitis if no action is taken.

KEY POINTS

- Ovarian abscessation is a rare cause of ‘oestrus not observed’ in dairy cattle.

- Treatment of ovarian abscessation is through unilateral ovariectomy, with a paralumbar approach on the /\ affected side.

- Histopathology can provide a definitive diagnosis of oophoritis and/or ovarian abscessation.

- Surgical treatment, through a flank laparotomy, is a treatment option for ovarian abscesses.

- There is insufficient evidence regarding the return to cyclicity, and future pregnancy in cattle following surgical treatment of ovarian abscessation.