Bovine viral diarrhoea virus (BVDV) is a common infectious disease of cattle subject to compulsory eradication schemes in many countries, including Scotland and Ireland. Estimated to cost the UK cattle industry £25–61 million pounds annually, it is the most costly single-agent infectious disease (Bennett, 2003). This is a result of its rapid spread within the herd, production losses (particularly due to its impact on fertility) and induction of immunosuppression; increasing incidence of other diseases (calf scour, respiratory disease, mastitis, lameness, infertility) (Evans et al, 2019). For more detail on the economic impact of BVDV, the reader is referred to the systematic review by Yarnall and Thrusfield (2017).

The primary source of the virus is a calf born persistently infected with BVDV (PI calf). They are tolerised to the virus in utero, and produce virus throughout life, in all body secretions. PI calves can die young, but one third of them may survive longer than 2 years (Booth and Brownlie, 2012), and enter into the breeding herd. PI calves are produced when a naïve dam is infected for the first time before 125 days of pregnancy.

The English eradication scheme (BVDFree) is a voluntary scheme launched in 2016 providing an online database of BVDV results for herds and individual animals (BVDFree, 2018). There is no joining fee, but farmers pay 25p (antigen/polymerase chain reaction (PCR)) and 50p (antibody) per test result uploaded. Farmers must commit to uploading all test results to the database; this occurs automatically if they indicate on their laboratory form that they are BVDFree members.1 BVDFree rules are similar, but not as stringent, as those of Cattle Health Certification Standards (CHeCS) and the two aim to work in tandem, with BDVFree offering an ‘entry level’ scheme.

Part 1 of this series discussed that the risk assessment for BVDV infection should focus on incoming animals to the herd, boundary fences and existing vaccination programmes (Button, 2020). Suitable testing can then follow with a choice of newborn screening or youngstock cohort surveillance, with optional bulk milk analysis in dairy herds. Farms that show initial evidence of endemic BVDV infection need to undertake further testing to discover the source.

Results of testing

Possible results from initial testing are discussed below.

Tag and test

Every calf born (including stillbirths and abortions) is screened for the presence of virus in order to identify a possible PI animal. A portion of ear tissue is removed during the ear tagging process, and this is collected into a vial for testing. The individual result will be one of the following:

- Empty vial — ear tissue was not collected in the vial during the tagging process. The calf needs to be retested for virus by tissue or blood sampling methods (Table 1)

- Insufficient sample — an inadequate amount of ear tissue was collected in the vial during the tagging process. The calf needs to be retested for virus by tissue or blood sampling methods

- Negative — the tissue sample tested negative for BVDV. The calf is not a PI animal

- Positive — the tissue sample tested positive for BVDV. The calf is viraemic and is either acutely infected or a PI. The calf needs to be retested for virus by tissue or blood sampling methods at least 4 weeks after the initial sample was collected.

Table 1. Summary of available bovine viral diarrhoea virus (BVDV) tests in the UK1

| Test | Detects | Sample required | Age requirement | Approximate cost | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tag and test | Virus | Ear tissue | Any | £2–3 for tag£4–5 for test | If positive must retest in 4 weeks |

| Serum antigen ELISA | Virus | Blood (plain tube) | > 4 weeks old | £4–6 | If positive must retest in 4 weeks |

| Serum PCR | Virus | Blood (unopened plain tube) | < 4–6 weeks old> 6 weeks old | £20£4–5 | If positive must retest in 4 weeks using ELISA |

| Serum PCR (pooled) | Virus | Blood (unopened plain tubes) | > 6 weeks old | £32.90 for 10 | If pooled sample positive, then separate out to find which individual sample is positive |

| Bulk milk PCR | Virus | Milk in preservative | N/A | £30–33 | Can detect 1 PI in 300 animals.Does not test non-lactating animals |

| Serology (ELISA) | Antibody | Blood (plain tube) | >9 months old to avoid confounding effect of maternal antibody | £3–4 | Only test unvaccinated animals.A young PI may be positive due to maternal antibody |

| Bulk milk serology | Antibody | Milk in preservative | N/A | £5–7 | Interpretation is complex if herd vaccinated |

Correct at the time of printing, however all test requirements and costs should be checked directly with the laboratory

ELISA = enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, PCR = polymerase chain reaction, PI = persistently infected

A member of staff at the veterinary practice should be trained to assess incoming tag and test results and know when it is necessary to contact the farmer regarding further testing.

The herd implications of tag and test results are as follows:

- All negative — no evidence of BVDV circulation in the breeding herd. This may be because of protection by vaccination of breeding animals and so one cannot draw the conclusion that no BVDV enters the premises, for example unvaccinated calves or stores may be affected

- Any positive result — the calf (and dam if still suckling) should be isolated until the second test takes place (at least 4 weeks after the first). The herd has a not negative status.

Check test

Calves are evaluated between 9–18 months old, testing sentinels in each group for antibody to determine whether BVDV has been circulating.

The possible results are:

- All five animals test negative. There is no evidence of BVDV circulation in that group of youngstock. This result is reliable only if the selection of animals for the check test was carried out correctly (see Button, 2020)

- One or two animals test positive. This is an inconclusive result for the presence of a PI in the herd. The first step is to check all the details used in selecting the animals for the check test — have they been together in a group for at least 2 months? Are they all homebred? Could any of them have been vaccinated? If no anomaly is found in animal selection, then further testing is required (see below)

- Three or more animals test positive. There is very likely a PI in that group (or has been, sometimes the PI has died before this age). Further testing should take place, in the form of a PI hunt.

Bulk milk

In dairy herds, bulk milk testing may provide additional information on BVDV status, but it is an optional part of assessment under the BVDFree scheme.

Possible results include:

- Negative for virus — there was no PI contributing to the bulk tank on that day (provided the maximum number of animals is not exceeded, see Table 1). Non-lactating animals such as dry cows, maiden heifers and of course the bull have not been tested; neither have cows under treatment whose milk was discarded

- Positive for virus — indicates active BVDV in lactating cattle, either acute infection or the presence of a PI, or both. Further testing should follow in individual animals, as a PI hunt.

- Negative for antibody — indicates a naïve unvaccinated herd. The cows are extremely vulnerable and biosecurity must be gold standard, or else vaccination introduced

- Positive or inconclusive for antibody — a vaccinated herd or a herd in which animals have been previously exposed. Interpretation of positive antibody results is notoriously complex (Booth and Brownlie, 2016), and ideally only longitudinal results should be used. Antibodies generated by BVDV are long-lasting and so if it is thought that the antibodies are historical; conducting a first lactation heifer screen may be helpful.

Action plan for BVDV control

The next step of the BVDFree process is to put in place an action plan. This will vary as to whether any evidence of BVDV was found during testing.

Action plan (negative results)

If no evidence of active BVDV is discovered during testing, then the action plan centres around protection of the herd. Biosecurity, and especially quarantine, must be excellent. The most important factors are incoming stock and boundary fences (see Button (2020) for further discussion).

Vaccination must be discussed as a protective measure for breeding stock. Even in a closed herd, entry of BVDV can still occur — the author has investigated three BVDV outbreaks in closed herds where the source was never discovered. Ideally, all breeding stock would be vaccinated well before the next pregnancy begins, using a vaccine licensed for fetal protection according to data sheet recommendations (Table 2). Remember to check the farmer's level of experience and competence with correct administration of vaccines.

Table 2. Summary of bovine viral diarrhoea virus (BVDV) vaccines licensed for fetal protection available in the UK

| Name of vaccine | Manufacturer | Type of vaccine | Licensed for | Primary course | Timing of primary course | Annual booster |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bovilis BVD | MSD Animal Health | Inactivated BVDV type 1 | Fetal protection | Two injections 4 weeks apart | From 8 months old. Second injection at least 4 weeks before breeding | Vaccinate 6 months after primary course. Then at annual intervals |

| Bovela | Boehringer Ingelheim | Modified live BVDV type 1 and type 2 | Calves: for reduction of hyperthermia, leucopenia and virus shedding Adults1: for fetal protection | Single injection | From 3 months old. At least 3 weeks before breeding | Vaccinate at accinate at annual intervals |

Do not use in breeding bulls

Action plan (inconclusive results)

- An empty vial or insufficient sample tag and test result would require the animal to be retested using blood or tissue tests (Table 1)

- An inconclusive check test result (one or two animals out of five are positive for antibody) will require further testing to determine whether there is active BVDV. Request the laboratory test any negative antibody samples for the presence of virus in case one or more PI animals have been sampled. A useful next step is to resample the individuals after 2 weeks to look for unusually persistent maternal antibody — the titres will decline between the two samples if this is the case. If the antibody levels are persistent, then sample five different animals from the same group.

Should the second group have any positive results, a PI hunt is probably wise (see below). If the second set of five are all negative, then examine the history of the original positive animals — were they all born at the same time, have they been in a separate group at any point, have they ever left the farm or been in contact with animals from other farms? Consider the herd history and likelihood of infection, together with the farmer's wishes, in order to decide whether further testing is appropriate.

- As previously discussed, a single bulk milk serology test is likely to be inconclusive, and serial quarterly tests are recommended to monitor BVDV in dairy herds by this method.

Action plan (positive results)

- Positive tag and test results indicate viraemia in the calf. It should be isolated and retested after 4 weeks with blood or tissue sampling.

If the second test is negative, then the calf was acutely infected and the source of the acute infection should be sought. If there is any concern that this source may continue to be present then the herd should be protected with vaccination, if it is not already.

If the second test is positive, then the calf is a PI animal and should be promptly culled. The mother should also be tested for virus to determine whether she is a PI. If she is also a PI, herd records need to be examined to establish how long she has been on the farm and the potential numbers of breeding stock that have been exposed to BVDV.

If the mother is not a PI, then the time of her early pregnancy should be evaluated for possible sources of a BVDV incursion. Other potentially infected dams from her cohort should be identified and isolated with their calf, from when they give birth until the calf's test result is known.

Testing of other stock may also be required depending on the circumstances of the case; for example, a PI hunt to identify how the dam may have become exposed.

- A positive check test (three or more animals out of five are positive on serology) indicates active BVDV infection in that group, provided the tested animals were correctly selected. Request the laboratory test any negative antibody samples for the presence of virus. This may identify a PI immediately. However, there may be more than one PI animal, so in any case all the youngstock need to be tested for virus (a PI hunt).

- A positive bulk milk antigen should be followed by a PI hunt in adults and youngstock.

Finding the persistently infected animals: a PI hunt

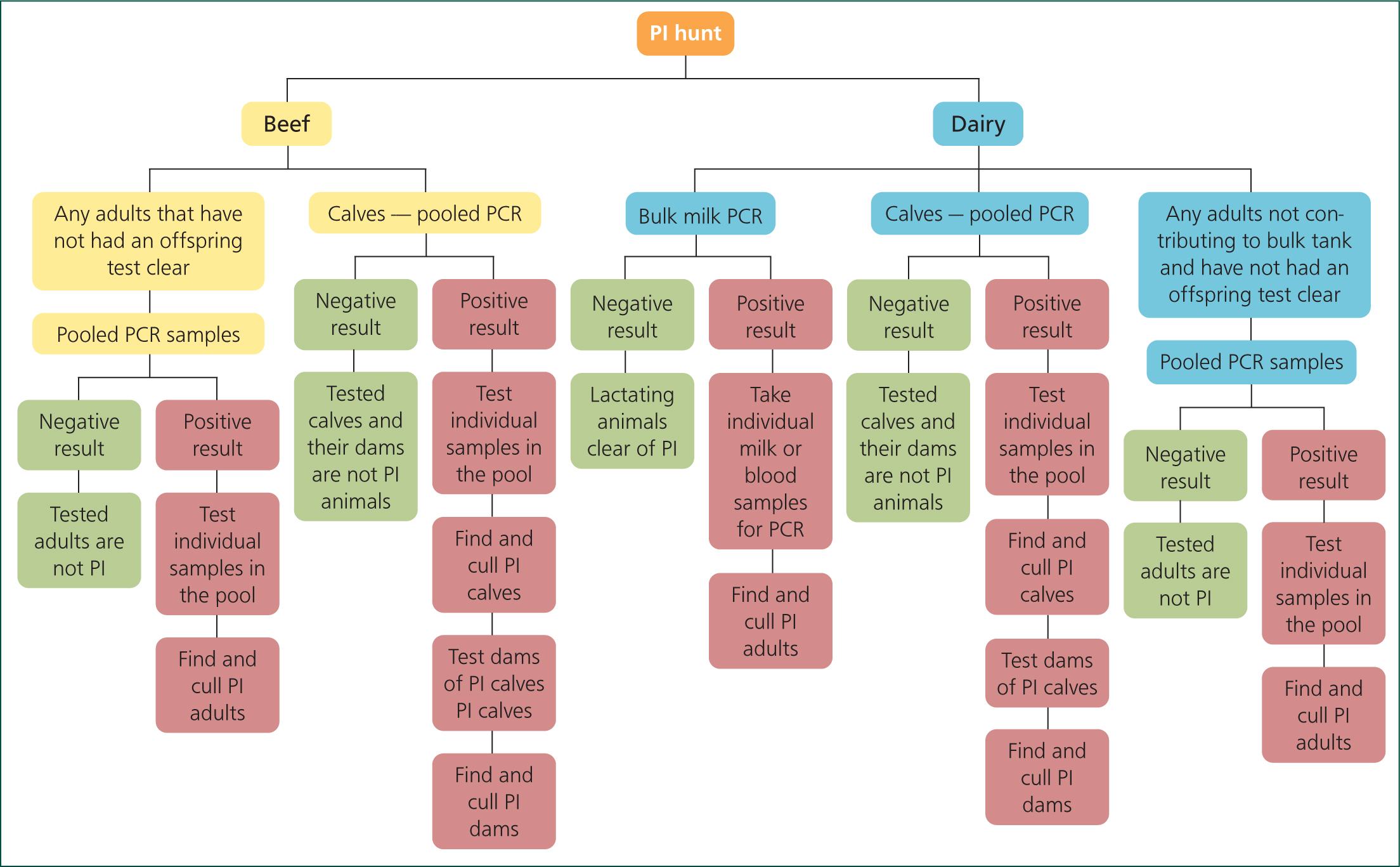

The process of a PI hunt aims to screen all animals on the holding for the presence of virus, using blood and/or milk testing.

To simplify the procedure and to save on costs, pooled samples should be used wherever possible — for example, bulk milk polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to screen lactating animals. For other animals, blood samples may be pooled in groups of ten — if a pool is identified as positive for virus, the separate samples will then be tested.

In breeding herds, the principle that a PI dam will always give birth to a PI calf can be used to simplify testing. If a calf is proved not to be a PI by virus testing, then it can be assumed that the mother is also not a PI, and so both animals can be considered cleared of suspicion. However, do bear in mind that mis-mothering in suckler herds is more common than might be supposed, and so if there is any doubt, both animals should be tested.

Check and double check that every single animal on the farm has been tested, either directly or indirectly, before the PI hunt is considered complete. Any animals testing positive for virus should of course be isolated and retested after 4 weeks, to distinguish between acute and persistent infection, although the farmer may wish to remove them from the herd straight away. Once confirmed as a PI, the animal should be immediately culled, although unfortunately many farmers are reluctant to cull PI animals; 18% do not do so according to a survey (BVDzero Congress, 2019; Waters, 2019) — and in fact one fifth of those farmers sell them to other farms.

The PI hunt process is summarised in the flow diagram in Figure 1.

Monitor progress

The last stage of the BVDV assessment process is to put in place a regular monitoring system so the farm can detect changes in its BVDV status. Farms may fall into three categories: not wishing to be accredited/BVDFree; wishing to belong to BVDFree; and CHeCS accredited.

Not wishing to be accredited/BVDFree

Farms that undertook BVDV testing for their own interest and are not wishing to be members of any scheme may decide not to do any further testing once they know their herd status. In the author's experience, clients that sell stores or finishing stock report they receive no financial benefit at the point of sale for being recorded as BVDFree. Clients in this situation should be advised that their BVDV status can change, and biosecurity and vaccination discussed as appropriate to the farm.

Other clients in this category may wish to continue testing but not belong to a scheme. They may test as and when they wish but should consider that the rules of BVDV schemes have been logically designed and if they truly wish to monitor BVDV status they would be advised to follow similar guidelines.

Dairy clients that are farm assured with Red Tractor are required to have a ‘BVD eradication programme designed in conjunction with the farm vet’ (Red Tractor, 2019), and so all clients in this category will need some form of ongoing testing, bulk milk at the very least.

Wishing to belong to BVDFree

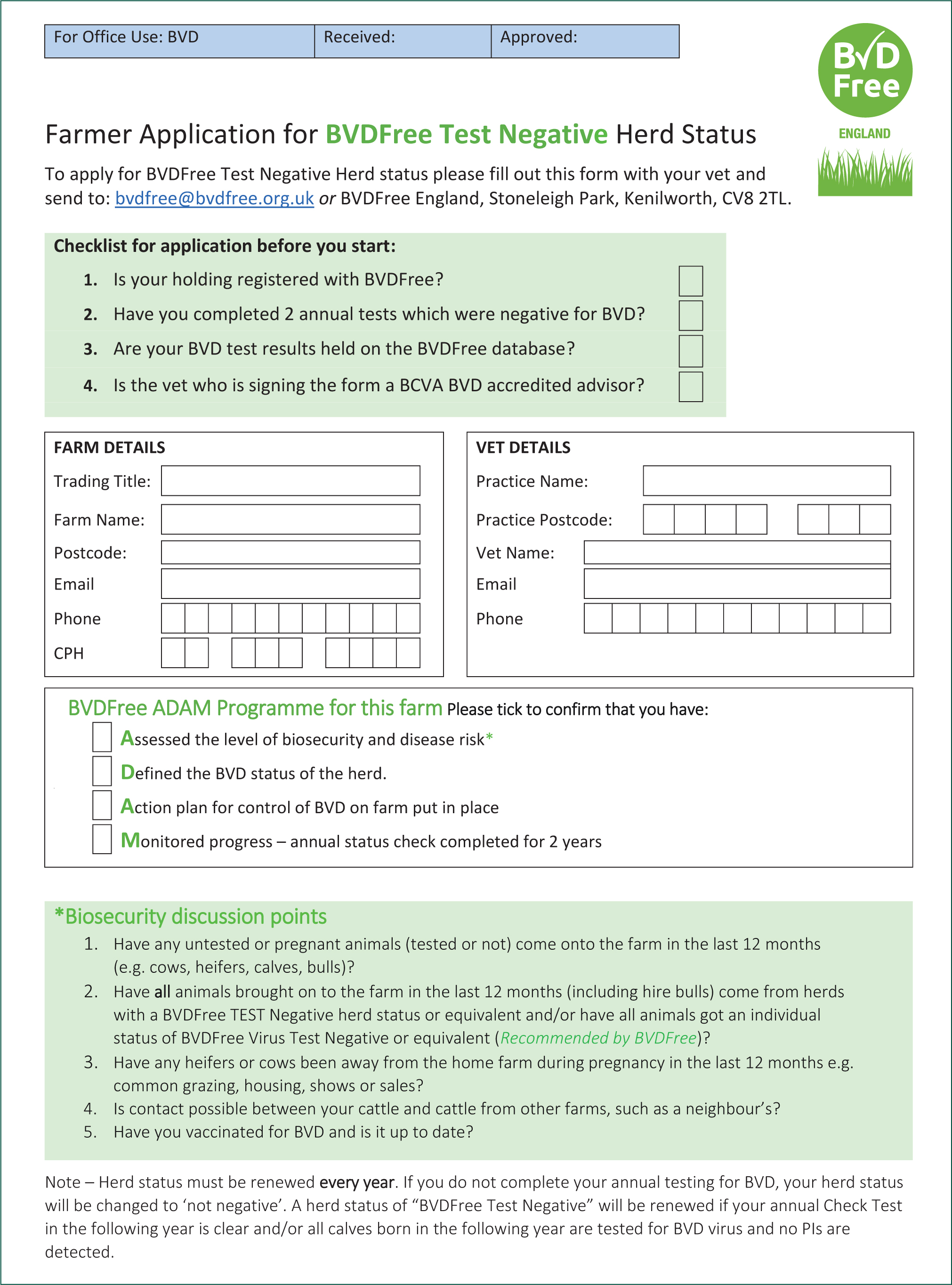

Clients interested in BVDFree membership need to undertake ongoing testing. If all tests are negative for a period of 2 years then they can apply for BVDFree Negative Herd status. This involves completing a form available on the BVDFree website (Figure 2) which must be signed by both the farmer and a veterinary surgeon who is an accredited BVD adviser.

Farmers may choose between tag and test or check test, both are eligible for the BVDFree scheme. Check tests must be performed according to guidelines (5–10 animals from each management group 9–18 months old, homebred and unvaccinated) every 7–12 months. Tag and test must be carried out on every animal born, including stillborn and aborted calves. In addition, every incoming animal must be tested, if using the tag and test system.

Testing procedures must continue in order to maintain negative status. Farmers may choose to change the type of test, for example, check test calves from 1 year and perform tag and test on the next batch of calves.

If any PI animals were discovered during the testing process then it is a requirement to test every calf born for the next 12 months.

Dairy farmers may choose to supplement testing with bulk milk antibody (if previously negative) or virus (if vaccinated or previously antibody positive).

Farmers must also commit to culling any PI calves when they sign up to BVDFree.

CHeCS accreditation

This represents to the highest level of BVDV status. Farmers wishing to become CHeCS accredited need to apply for member-ship and pay an annual membership fee (currently £75 for the Premium Cattle Health Scheme, £45 for BVD only or £85 for multiple diseases with HiHealth Herdcare).

The testing requirements are as for BVDFree membership, with the following additional requirements:

- Added animals must be tested for virus AND antibody 28 days after entry into quarantine. Any positive results will extend the quarantine period for a further 28 days. Added cattle that are pregnant cannot be released from quarantine until the calf has been born and tested. Bulls require a minimum 10 week quarantine period because of the risks of virus shedding in the semen.

- Fields must have double fencing where there is grazing adjacent to cattle not accredited.

- Cows that have aborted should have a blood test.

- This is likely to be cost-effective only for pedigree farms selling high value breeding stock.

Conclusion

Clients have a number of options regarding testing strategies and membership of BVDV schemes, and the role of the veterinary surgeon is to offer informed advice as to the appropriate system for the individual farm, and to provide discussion and recommendations on results of BVDV testing. Both the existence of high specificity and sensitivity tests, and the epidemiology of BVDV with the PI animal as the key virus source mean that BVDV testing and eradication on farms can be both satisfying and successful.

KEY POINTS

- Two years of negative testing on a farm qualifies them to apply for bovine viral diarrhoea virus (BVDV) free status.

- Positive results on initial screening tests should be followed up with further testing, usually a persistently infected (PI) animal hunt.

- The key step in eradication is identification and prompt removal of PI animals.

- BVDFree and Cattle Health Certification Standards (CHeCS) accreditation schemes offer recognition of a farm's status.