Bovine viral diarrhoea virus (BVDV) is a common virus of cattle subject to compulsory eradication schemes in many countries, including Scotland and Ireland. Estimated to cost the UK cattle industry £25–61 million pounds annually, it is the most costly single-agent infectious disease (Bennett, 2003). This is because of its rapid spread within the herd, production losses (particularly due to its impact on fertility) and induction of immunosuppression increasing incidence of other diseases (calf scour, respiratory disease, mastitis, lameness, infertility) (Evans et al, 2019). For more detail on the economic impact of BVDV, the reader is referred to the systematic review by Yarnall and Thrusfield (2017).

The primary source of the virus is a calf born persistently in-fected (PI) with BVDV (PI calf). They are tolerised to the virus in utero, and produce virus throughout life, in all body secretions. PI calves can die young, but one third of them may survive longer than 2 years (Booth and Brownlie, 2012), and enter into the breeding herd. PI calves are produced when a naïve dam is infected for the first time before 125 days of pregnancy.

The English eradication scheme (BVDFree) is a voluntary scheme launched in 2016 providing an online database of BVDV results for herds and individual animals. Prospective purchasers are encouraged to check an animal's status online before buying (Figure 1). There is no joining fee, but farmers pay 25p (antigen/polymerase chain reaction (PCR)) and 50p (antibody) per test result uploaded. Farmers must commit to uploading all test results to the database; this occurs automatically if they indicate on their laboratory form that they are BVDFree members. They must also commit to the prompt culling of any PI calf. BVDFree rules are similar, but not as stringent, as those of CHeCS and the two aim to work in tandem with BDVFree off ering an ‘entry level’ scheme.

A Rural Development Programme for England (RDPE) funded project ‘BVD — Stamp It Out’ is currently running in England (2018–2021), with funding provided for breeding herds for BVD assessment, testing and an action plan, aiming to promote BVD-Free and engage the farming community with BVDV eradication.

Additional encouragement for eradication on dairy farms was provided recently, when Red Tractor (dairy) standards were altered to include: ‘BVD must be managed through a BVD eradication programme designed in conjunction with the farm vet’ (Red Tractor, 2019).

The initial steps of the BVDFree programme are summarised using ADAM: assess disease risk; define herd status; action plan for BVD control; monitor progress. These correspond to the steps discussed over this series of two articles.

Assessing herd risk

The first step in assessing a herd is to identify the risk of current infection by evaluating biosecurity and management. Primarily, this should focus on incoming stock (purchased animals and existing stock returning to the holding), boundary fences and vaccination status. Minor transmission routes include contaminated fomites, such as vehicles and equipment. If not already known, establishing at this stage the primary purpose of the farm and the types of stock present will help in planning tests and prioritising goals.

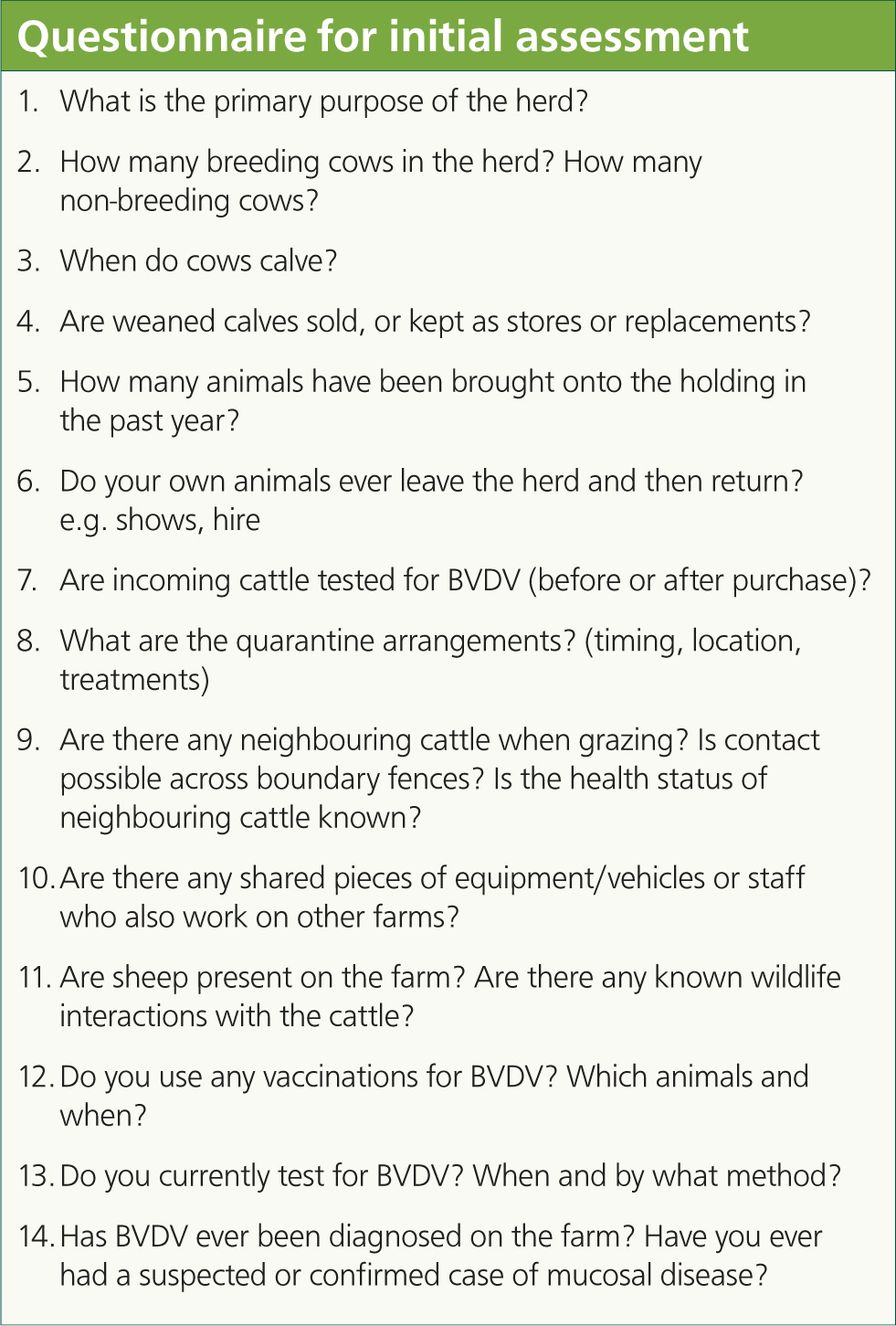

Having a standardised questionnaire can be very helpful in this initial process, even if the veterinary surgeon feels they know the farm well. Specific questions are essential, as farmers will often answer ‘Yes’ to the question ‘Is this a closed herd?’, but a very different answer is given to ‘How many animals have been brought onto farm in the last year?’ At the 2019 BVDzero Congress it was revealed that in England 62% of farmers defined their herds as closed; yet of this number 19% introduced bulls, 2% replacements and 1% fatteners (BVDzero Congress, 2019; Waters, 2019). Figure 2 shows a questionnaire written by the author to use in the BVD — Stamp It Out project.

Biosecurity

The risk of BVDV being endemic in a herd is most affected by contact with other animals, so purchase of stock, quarantine arrangements and contact across fences (gaps of less than 3 m) are major risk factors (Larghi, 2018). It may be worth stressing to farmers that exercising good management in these areas is beneficial for many diseases, not just BVDV.

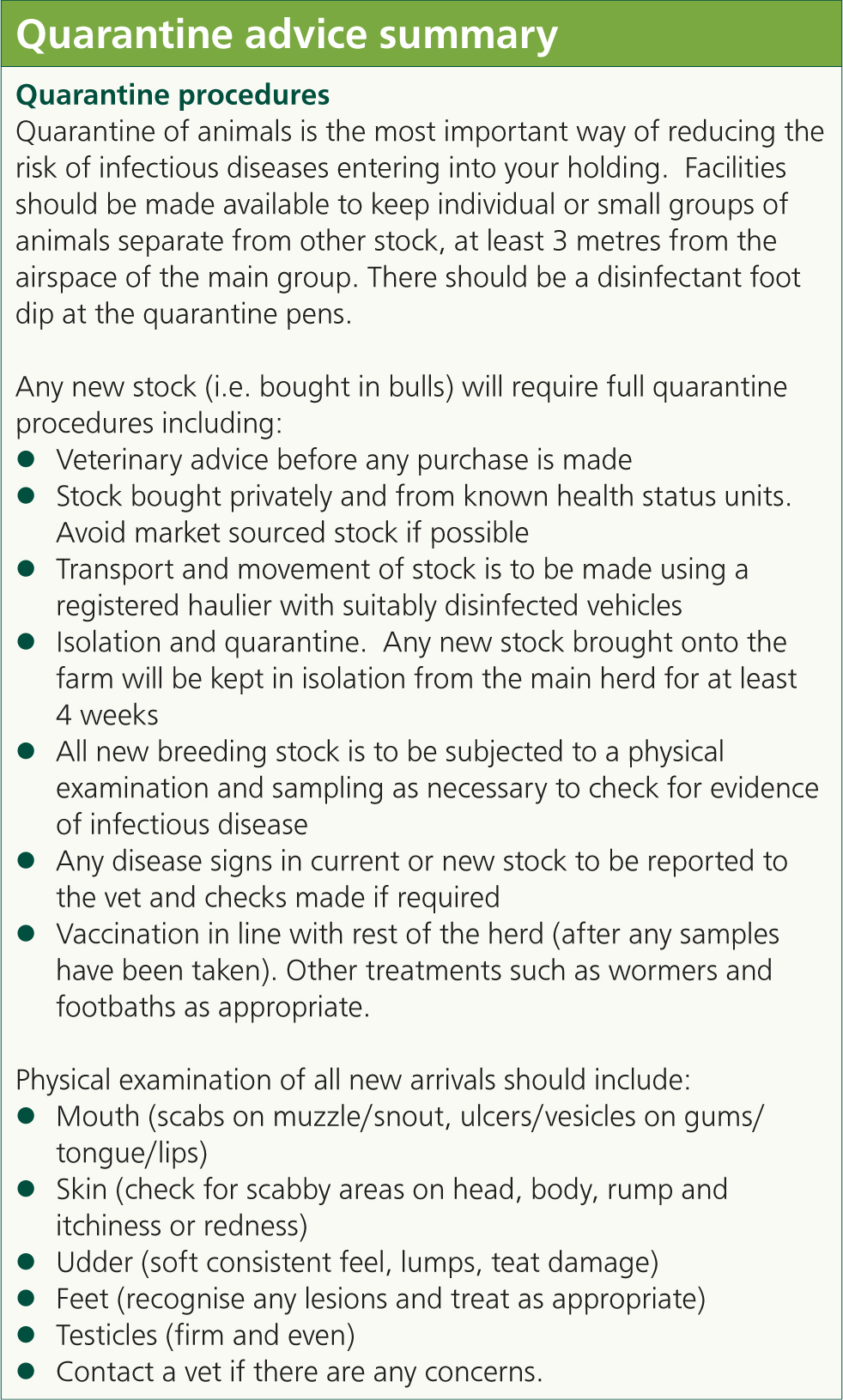

The author found that every single farm from her practice that had enrolled in the BVD — Stamp It Out project could make at least one improvement to their biosecurity arrangements. Lack of or insufficient quarantine was a common feature (88% of farms that were not closed), and therefore a page on quarantine procedure was included as standard in the final report provided to the farm (Figure 3). Bulls must be quarantined for extended periods of time because after an acute infection, semen can contain BVDV for up to 9 weeks (Lanyon et al, 2014). Therefore, breeding bulls should be quarantined for 10 weeks ideally. (This is a requirement of CHeCS accreditation schemes (CHeCS, 2019)).

BVDV testing should preferably occur before purchase and should confirm that the purchased animal is not PI (virus testing). A previous result is valid since PI status is unchanging. It is important to emphasise to farmers that, if purchasing pregnant animals, there is no way to test the unborn calf. Therefore, the mother should give birth in isolation and remain so until the calf is tested. The risk of introducing acutely infected animals should also be considered and an appropriate quarantine period should prevent any transmission to other stock.

Boundaries are another important element. If adjacent stock are present without double fencing, then nose-to-nose transmission may well occur between animals from different holdings.

During this initial conversation, the biosecurity level on the farm can be assessed (and could be graded with a traffic light system if desired). Farms with a high risk of BVDV entry should make biosecurity improvements if possible, before continuing with assessment of BVDV herd status. These farms should also be encouraged to use vaccination to protect stock if other means are not available.

Vaccination

Discussing current use of vaccination will require detailed questioning about which animals are vaccinated and when. Enough information must be gleaned to demonstrate farmers are using the vaccine according to the datasheet and that all vulnerable stock are protected in advance of the breeding season. Table 1 summarises current BVDV vaccines available in the UK.

Table 1. Summary of vaccines available in the UK

| Name of vaccine | Manufacturer | Type of vaccine | Licensed for | Primary course | Timing of primary course | Annual booster |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bovilis BVD | MSD Animal Health | Inactivated BVDV type 1 | Fetal protection | Two injections 4 weeks apart | From 8 months old. Second injection at least 4 weeks before breeding | Vaccinate 6 months after primary course. Then at annual intervals |

| Bovela | Boehringer Ingelheim | Modified live BVDV type 1 and type 2 | Calves: for reduction of hyperthermia, leucopenia and virus shedding.Adults1: for fetal protection | Single injection | From 3 months old.At least 3 weeks before breeding | Vaccinate at annual intervals |

| Rispoval 4 | Zoetis | Inactivated BVDV type 1 alongside BRSV, PI3 and IBR | Prevention of leucopenia and viraemia due to BVDV (NOT fetal protection) | Two injections 3 to 4 weeks apart, from 12 weeks of age | Second injection at least 2 weeks before stressful events | Duration of immunity 6 months |

| Rispoval 3 | Zoetis | Inactivated BVDV type 1 alongside BRSV and PI3 | Prevention of leucopenia and viraemia due to BVDV (NOT fetal protection) | Two injections 3 to 4 weeks apart, from 12 weeks of age | Second injection at least 3 weeks before stressful events | Duration of immunity 6 months |

| Bovalto Respi 4 | Boehringer Ingelheim | Inactivated BVDV type 1 alongside BRSV PI3 and Mannheimia haemolytica | To reduce virus excretion due to BVDV (NOT fetal protection) | Two doses 3 weeks apart | From 2 weeks of age if dam is non-immune | Revaccination at 6 months |

Do not use in breeding bulls.

BVDV = bovine viral diarrhoea virus, PI3 = parainfluenza 3, IBR = infectious bovine rhinotracheitis, BRSV = bovine respiratory syncytial virus

Multiple studies demonstrate that farmers are often not storing or administering vaccines in line with manufacturer guidelines (Meadows, 2010; Small et al, 2019). In the study by Meadows (2010), the most common problem was failing to observe the correct time interval between injections for a primary course. Vaccination of stock with concurrent disease or negative energy balance may not lead to a protective immune response. This is also a good time to explain to farmers why a vaccinated herd is not necessarily a BVDV-free herd (first, because the PI animal cannot respond to vaccination and may go on to produce a PI calf; and second because individuals being vaccinated may be suffering from BVDV-induced immunosuppression and so unable to respond to the vaccine).

Vaccination programmes may affect the testing procedure — in particular, in dairy herds the interpretation of bulk milk antibody in a vaccinated herd is complex. Animals vaccinated with an inactivated vaccine will tend to be seronegative after 3 months (using a p80 antibody-enzume-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)); live vaccines mirror natural infection and serum antibodies are long-lasting. Multivalent respiratory vaccines are likely to interfere with the results of a youngstock check test (see below). There is also a theoretical risk that newborn calves may test positive for virus by PCR if the mother was vaccinated with a live vaccine.

Assessing herd status

Once the first step is complete, the current BVDV status of the herd can be established as negative or not negative, using testing. There are a number of different tests available to evaluate anti-bodies and virus, summarised in Table 2. The primary decision is whether to screen every newborn animal to determine if they are PI or whether to sample sentinel animals from youngstock cohorts (‘check test’). From Table 2 it can be seen that for larger herds, it is more cost effective to perform a check test (the cut-off point is at about 40–50 animals).

Table 2. Summary of available bovine viral diarrhoea virus tests in the UK1

| Test | Detects | Sample required | Age requirement | Approximate cost | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tag and test | Virus | Ear tissue | Any | £2–3 for tag£4–5 for test | If positive must retest in 4 weeks |

| Serum antigen ELISA | Virus | Blood (plain tube) | >4 weeks old | £4–6 | If positive must retest in 4 weeks |

| Serum PCR | Virus | Blood (unopened plain tube) | <4–6 weeks old>6 weeks old | £20£4–5 | If positive must retest in 4 weeks using ELISA |

| Serum PCR (pooled) | Virus | Blood (unopened plain tubes) | >6 weeks old | £32.90 for 10 | If pooled sample positive, then separate out to find which individual sample is positive |

| Bulk milk PCR | Virus | Milk in preservative | N/A | £30–33 | Can detect 1 PI in 300 animals.Does not test non-lactating animals |

| Serology (ELISA) | Antibody | Blood (plain tube) | >9 months old to avoid confounding effect of maternal antibody | £3–4 | Only test unvaccinated animals.A young PI may be positive due to maternal antibody |

| Antibody | Milk in preservative | N/A | £5–7 | Interpretation is complex if herd vaccinated |

Correct at the time of printing, however all test requirements and costs should be checked directly with the laboratory.

ELISA = enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, PCR = polymerase chain reaction, PI = persistently infected

Newborn screening

This would usually be via tag and test methods, testing for virus to establish which animals are viraemic. Two years of clear tests on every animal born would be required for BVDFree Negative Herd Status.

Any positive animal should ideally be isolated and resampled 4 weeks later to exclude the possibility of acute infection (however, some farmers will choose to cull the animal straight away). If two positive results are found, then the individual is PI and must be culled. The farmer needs to be aware of the need to cull a PI animal before starting any testing programme, as in the author's experience many are reluctant to cull PI calves (18% do not do so according to one recent survey (Waters, 2019) and one fifth of those farmers sell them to other farms).

For BVDFree membership and for CHeCS accreditation schemes, newborn screening must also include stillborn or aborted calves. This is particularly important when it is considered that 13% of fetal calves are PI compared with only 1–2% of liveborn calves (Nettleton and Entrican, 1995). Guidance from the BVD-Free scheme is that any aborted calf found should be tested, even those that have been lost in early or mid-pregnancy. Bought-in animals must also be tested.

The tag and test system is favoured by many farmers as they are in control and the calf does not need extra procedures. A number of companies provide tag and test services. British Cattle Movement Service tags are available for routine identification of calves and management tags are available for bought-in animals or retesting.

Tag and test results are sent directly to the farmer and copied to their veterinary practice. The practice must develop a system for filtering the incoming results: a trained member of staff needs to view them and follow up those requiring further testing (empty vial, insufficient sample, positive result).

Check test

The goal of the check test is to sample youngstock for exposure to BVDV, with the aim of identifying a group of youngstock containing a PI animal, by the fact that its contemporaries are antibody positive. A minimum of five animals is needed from each separately managed group of youngstock; this provides 97% confidence of revealing 50% seroprevalence in the group. For BVDFree, a minimum of ten animals from the herd is recommended, so if young-stock are all in one group, then ideally ten should be sampled from that group.

Carefully plan the check test by inquiring in detail about young-stock groups, when the groups are formed, and whether there is any movement or contact between groups. The youngstock cohort must have been together for at least 2 months. Incorrect selection of which animals to test is a common reason for check test failure.

Ideally only animals over 9 months of age should be sampled, because of the persistence of maternal antibody. Levels have usually declined sufficiently by 9 months, but occasionally it is necessary to resample and demonstrate a falling titre. If there are fewer than five animals in the group 9–18 months old, include animals from 6–9 months old to make up the minimum numbers. In herds that wish to sample earlier for convenience, it is possible to sample 6–9 month old calves, but it is recommended to sample ten per group and advise the farmer that retesting may be required. In smaller herds with fewer than ten youngstock, then sample all the calves in the age range 6–18 months and animals over 18 months old that have been on the farm since birth, to reach the minimum numbers. If unsure, always discuss with the laboratory before commencing testing.

Only homebred animals must be used for the check test. Animals to be sampled must not have been vaccinated for BVDV — this includes the multivalent respiratory vaccines such as Rispoval 4 (Zoetis). In the author's experience, this can lead to a narrow window in some beef suckler farms, for example the spring calves that are housed, weaned and vaccinated simultaneously in autumn. If farmers can be persuaded to blood test while at grass or delay vaccination until after housing this makes the situation easier.

If coordinating the right animals for the check test proves excessively difficult within the farm system, or insufficient information is available from the farmer, this is probably an indication to move to newborn screening.

The advantage of the check test is that it identifies recent and active infection on the holding, since the calves must have been exposed in their lifetimes. It negates the need for testing each and every calf which may be onerous on some farms (or retesting that is forgotten or the calf has already been sold or turned out). On the larger units it is more cost effective than newborn screening since the sample size remains the same regardless of the size of the group.

Bulk milk sampling

For dairy herds, bulk milk sampling can provide additional information and is very cost effective. Dairy herds reluctant to comply with the Red Tractor requirement to have an eradication plan in place can usually be persuaded to do a bulk milk analysis.

Bulk milk testing is an optional part of the BVDFree scheme. Both antibody and PCR tests are available and which to use depends on the history of the herd.

In naïve herds, bulk milk antibody provides a sensitive and specific measure for demonstrating lack of exposure in animals contributing to the bulk tank.

However, in exposed or vaccinated herds the interpretation is more difficult as antibody levels both persist and fluctuate. It is not recommended to perform a single bulk milk antibody test in a vaccinated herd, although with care they can be used longitudinally (Booth and Brownlie, 2016).

If the herd is not vaccinated but has a positive bulk milk anti-body, a first lactation screen may help establish the recency of the infection. However, a check test is a more sensitive way of detecting an actively infected herd (Booth and Brownlie, 2016).

Bulk milk PCR can be used to detect the presence of a PI animal contributing to the bulk tank and is extremely sensitive — down to one PI in 300 animals according to most laboratories. It could be used as a quick screen during initial testing or during a PI hunt if initial testing is suggestive of a PI animal in the herd. Remember of course that lactating cows under treatment, dry cows, the bull and replacement heifers are not tested by this method, and will need to be separately tested.

Table 3 summarises testing methods. BVDFree also produces excellent flow diagrams summarising the testing process (BVD-Free, 2018).

Table 3. Possible testing strategies for assessing bovine viral diarrhoea virus status1

| Animals required | Sample required | Test required | Results indicate… | Relative cost | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Check test | 5 animals aged 9–18 months old from each management group | Red top blood tube | Serum antibody ELISA | Previous exposure to infection and probability of a PI in the group (or maternal antibody in <9 months old, or incorrect selection of vaccinated animals) | Approximately £200 for ten calves allowing for veterinary time and laboratory fees |

| Tag and test | Every animal born including stillbirths | Ear tissue in barcode labelled tube | Virus PCR or antigen ELISA | Calf viraemic or not viraemic | £4–6 per calf |

| Bulk milk PCR | Tests all lactating animals (will detect one PI in 300) | Milk in preservative | Virus PCR | Viraemic animals contributing to bulk tank | £30–33 |

| Bulk milk serology | Tests all lactating animals | Milk in preservative | Antibody ELISA | Vaccinated or exposed animals contributing to bulk tank | £25–30 annually for quarterly testing |

Correct at the time of printing, however all test requirements and costs should be checked directly with the laboratory.

PI = persistently infected, PCR = polymerase chain reaction, ELISA = enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

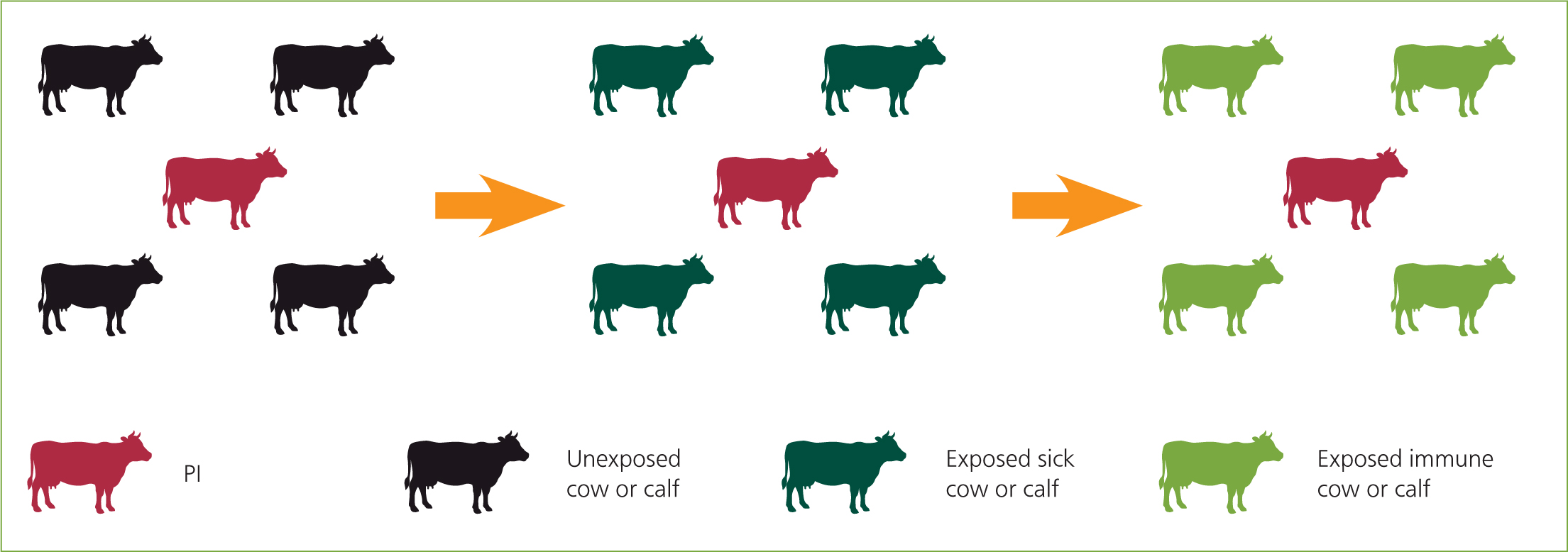

The author has found that many farmers are confused about the difference between antibody and antigen testing. Clients have phoned after a positive check test thinking that all the antibody positive animals are PI and will need to be culled. As far as possible, try to explain about possible results before starting testing. During farmer training, the author uses coloured cows to represent naïve, acutely infected, exposed/recovered and PI calves (Figure 4). This was helpful when talking about the results, e.g. ‘There are four green calves out of five tested, we need to look for a red calf’, or ‘The ear tag is positive, we need to test further to see if the calf is red or dark green’.

Once results are received, the herd can be classed as negative or not negative. Further testing will be required to follow up positive results. If the herd tests negative, then procedures must be put in place to protect the herd. These stages are all discussed in part 2 of this series of articles.

Conclusion

Farms are complex systems and any successful attempt to eradicate BVDV from a farm will require a detailed knowledge of the farm management. Time invested at this stage will reap rewards later. Similarly, careful planning of BVDV testing strategies will take into account the farmer's goals, the type of enterprise, resources available and management of cattle.

KEY POINTS

- Bovine viral diarrhoea virus (BVDV) can be successfully eradicated at herd level.

- BVDFree and CHeCS accreditation schemes offer recognition of a farm's status.

- Initial and detailed assessment of the herd is an essential step and a questionnaire may be used to ensure all key information is gathered.

- Careful planning of testing strategies will help veterinary surgeons and farmers to choose from newborn screening or check test, with optional bulk milk analysis in dairy herds.

- Discussion with the client about costs, possible results and implications of positive results must occur before starting the process.