Lameness causes significant economic losses on UK sheep farms because of reduced productivity, and the increased labour and expenditure associated with treatment (Nieuwhof and Bishop, 2005; Wassink et al, 2010a). Lameness is also a major concern for animal welfare (Phythian et al, 2011). Two contagious diseases, footrot (encompassing scald and severe footrot) and contagious ovine digital dermatitis (CODD), are the most common causes of lameness in UK sheep flocks, affecting >95% and 35–48% of flocks respectively (Angell et al, 2014; Winter et al, 2015). These diseases account for 68% and 12% of lesions respectively in affected flocks (Winter et al, 2015). Treatment and control of footrot and CODD have been discussed in detail in recent articles (Clifton and Green, 2017; Green and Clift on, 2018; Duncan and Angell, 2019) and therefore will not be discussed here.

Th ere are several non-contagious foot diseases that cause lameness in sheep, these include granulomas, shelly hoof and white line abscesses. While these lesions are less prevalent than contagious causes of lameness across all farms, they are more prevalent than footrot and CODD on some farms (Kaler and Green, 2008).

Granulomas

Clinical presentation

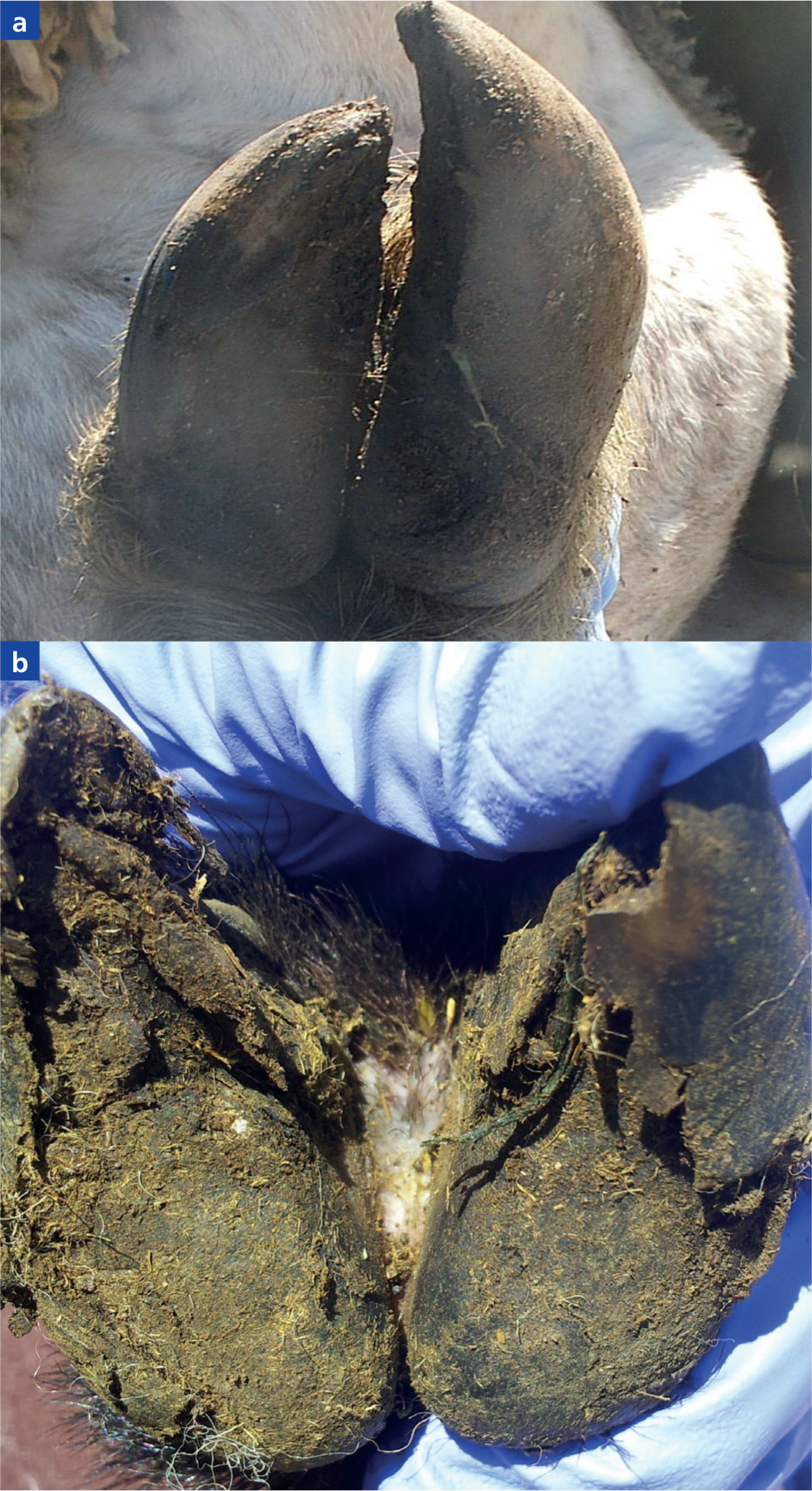

Granulomas (oft en referred to as ‘strawberries’) are proliferations of highly vascularised connective tissue that protrude through disrupted hoof horn (Figure 1). They are most commonly found near the toe, but can be present anywhere on the sole or at the wall horn junction. Granulomas are extremely painful and sheep are usually severely lame. They oft en cause a chronic lameness, and because the sheep is not bearing weight on the affected limb, hoof horn will become overgrown (Figure 1 and Box 1), which can hide the granuloma from view.

Aetiology and epidemiology

Granulomas occur in 54–63% of flocks, and while the majority of flocks have low prevalence of these lesions (<1%), a small proportion of farmers report figures of up to 8% sheep affected (Reeves et al, 2019).

Box 1.Changes in appearance of hoof horn

- Mis-shapen hoof horn (Figure 2) usually occurs as a result of chronic footrot or contagious ovine digital dermatitis (CODD), or in response to over-trimming. It is very difficult to correct in more severe cases, and therefore culling may be advisable.

- Overgrown hoof horn (Figure 3) can occur when sheep are on soft ground, frequently this is when they are housed, or during spring and autumn when the ground is wet. Hooves will wear down again when the ground becomes harder (Smith et al, 2014). Hoof horn may also become overgrown if a sheep is chronically lame because the sheep does not bear weight on the affected limb. This will usually just affect one foot, whereas changes in horn length in response to ground conditions will affect multiple feet. Overgrown hoof horn does not usually cause lameness and therefore does not require correction. Under specific circumstances, for example in sheep that are housed for prolonged periods, or in cases where the horn is affecting mobility, careful corrective trimming can be used.

- Horizontal grooves in all four hooves often develop following laminitis, and these take several months to grow out. They may periodically cause cracks in the hoof and lameness (Winter, 2004b). Shallower horizontal grooves can also indicate periods of varying nutrition or metabolic stress.

- Horizontal cracks, usually 1–2 cm in length, may develop at the site of previous white line abscesses or CODD lesions (Figure 4).

- Vertical sandcracks are reasonably common and may result from damage to the coronary band (Winter, 2004b).

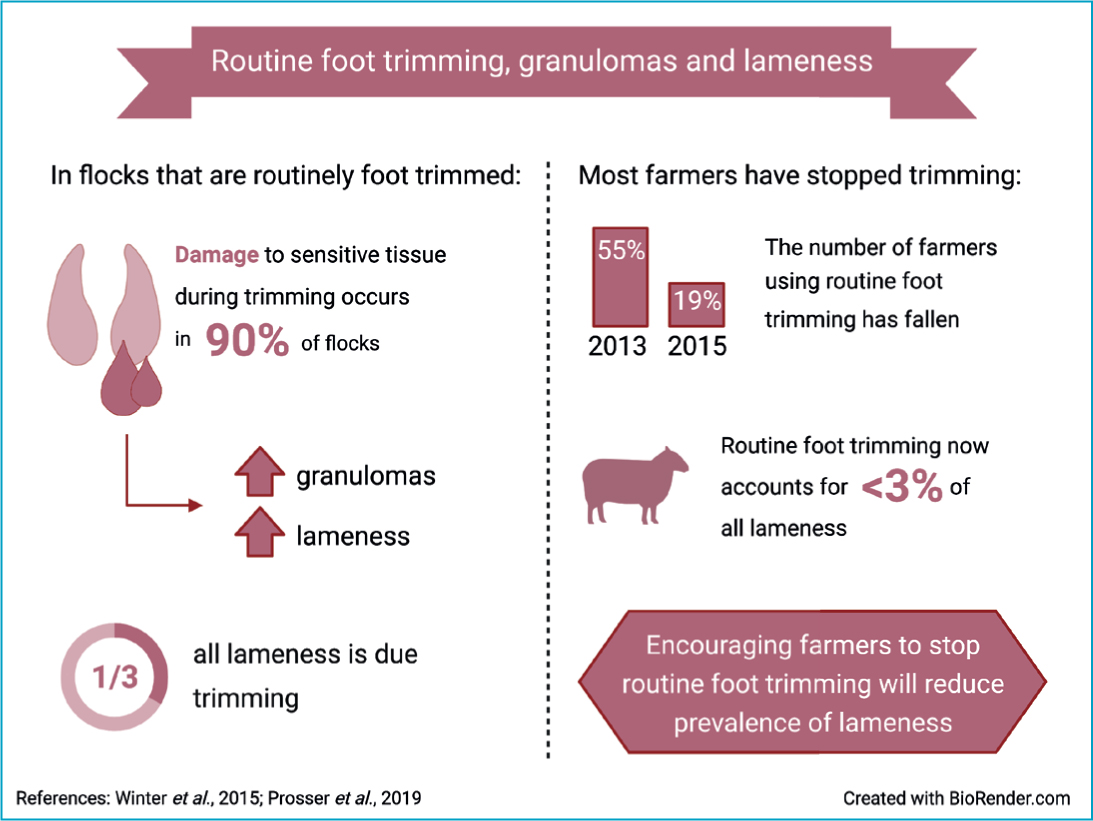

The tissue proliferation that forms a granuloma is a response to damage to tissue beneath the horn capsule. Granulomas are more prevalent in flocks that practise routine and/or therapeutic foot trimming than those that do not practise foot trimming (Reeves et al, 2019), because over-trimming damages the sensitive tissues beneath the horn capsule (Box 2). Recent evidence shows that granulomas are more prevalent in flocks that are routinely footbathed and where formalin is used compared with those that are not footbathed. This is possibly because high concentrations of formalin damage any exposed subcapsular tissues, leading to a proliferative response (Reeves et al, 2019). It is also suggested that granulomas can occur as a result of untreated severe footrot or CODD. The number of farmers who promptly treat individual lame sheep has recently decreased (Prosser et al, 2019), and therefore this aetiology for granuloma formation may become more common. Granulomas can make sheep susceptible to getting footrot because Dichelobacter nodosus, the cause of footrot, infects the granuloma. Sheep with granulomas may therefore act as a reservoir of D. nodosus within a flock.

Box 2.

Treatment and control

Granulomas are difficult to resolve; suggested approaches include ligation, bandaging the foot with copper sulphate, or surgical removal under local anaesthesia. Systemic antibiotic treatment is indicated where secondary infection is present, or where untreated footrot or CODD are the likely cause of the granuloma, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are recommended because granulomas are extremely painful. Following treatment sheep should be monitored daily and so need to be kept near the farm; culling is likely to be the best option if treatment is unsuccessful. Culling a group of chronically lame sheep significantly reduces the labour required to re-treat lame sheep, and also reduces lameness prevalence in a flock (Witt and Green, 2018). This is partly because it reduces the number of lame sheep, but also because, as above, sheep with granulomas act as a reservoir for D. nodosus, and so these sheep spread footrot.

It is far better to prevent granulomas occurring by not practising routine foot trimming or routine footbathing (Box 3). Prompt treatment of individual sheep with footrot and CODD will reduce the prevalence of untreated lesions that may lead to granuloma formation.

Box 3.The use of footbathing in sheepFootbathing to treat outbreaks of interdigital dermatitis in lambs is the only footbathing practice that is effective to reduce prevalence of lameness (Winter et al, 2015; Witt and Green, 2018). We have known for some time that routine footbathing is associated with higher prevalence of lameness, and footbathing is not effective for treating footrot and contagious ovine digital dermatitis (CODD) (Winter et al, 2015); individual antibiotic treatment is best practice for both these conditions (Kaler et al, 2010). In addition to this, the recent evidence from Reeves et al (2019) that footbathing is linked to higher prevalence of both granulomas and shelly hoof indicates that footbathing should not be considered part of good practice for managing lameness. However, routine footbathing is viewed by many farmers as an ideal management for controlling footrot (Wassink et al, 2010b). Between half and two thirds of farmers use routine footbathing (Prosser et al, 2019), and almost three quarters of these farmers are using formalin (Winter et al, 2015). Encouraging farmers to stop routine footbathing will reduce the prevalence of granulomas and shelly hoof. The time and money saved by stopping routine footbathing (Winter and Green, 2017) can then be targeted for more effective control of contagious foot diseases, such as prompt treatment of individual lame sheep (Clifton and Green, 2017; Duncan and Angell, 2019).

Shelly hoof

Clinical presentation

Shelly hoof (also known as white line separation or white line disease) is a detachment of the hoof horn wall from the underlying epidermis (Figure 5a). It typically occurs on the abaxial wall. The separation itself does not usually cause lameness, although it may do so if horn breaks off leaving sensitive laminae exposed, particularly around the toe (Liz Nabb, personal communication). Separation of the white line also leaves a cavity (Figure 5a) in which debris can become impacted. Foreign bodies, such as thorns or stones, can then penetrate into sensitive tissues, leading to abscess formation and severe lameness.

Aetiology and epidemiology

Feet affected by shelly hoof have poor horn development. This is characterised by microfissures in the dorsal horn, separation and degeneration of cell membranes, and poorly keratinised epithelial horn cells, making the hoof physically weak (Conington et al, 2010).

Shelly hoof occurs in 58–76% of flocks (Reeves et al, 2019), and while most affected flocks report low prevalence of lesions, prevalence can be very high (35–95%) in certain flocks (Conington et al, 2010; Reeves et al, 2019).

The risk factors for shelly hoof are not fully understood. In a study of Texel and Blackface sheep in the UK, Conington et al (2010) found evidence for a genetic component to the disease. Associations with nutritional imbalance and rough or stony ground are also suggested, however, these are based on extrapolation from risk factors for white line disease in dairy cattle rather than research on the condition in sheep (Winter and Arsenos, 2009). Shelly hoof is also more prevalent in flocks that are routinely foot-bathed, possibly associated with formalin footbaths (Reeves et al, 2019). At concentrations >5%, formalin causes inflammation and hardening of tissues (Pryor, 1959; Ross, 1983; Thavarajah et al, 2012); these effects could exacerbate the hoof horn degeneration that occurs in shelly hoof.

Reeves et al (2019) also found that shelly hoof was more likely in flocks with low stocking density. Further research is needed to better understand this association between shelly hoof and stocking density but it might be explained by common features of the environment of low stocked flocks, for example rough terrain that damages feet or poor nutrition from low pasture quality that leads to poor hoof horn formation. Certain breeds of sheep are also more commonly kept in more extensive low stocked environments.

Treatment and control

Sheep with shelly hoof that are not lame do not need treatment. It has been suggested that loose flaps of horn should be trimmed to prevent lameness (Figure 5b), but there is no evidence that such trimming is effective and care must be taken to avoid trimming into sensitive tissue because of the risks of granulomas (see above). When sheep are lame remove impacted dirt and debris in horn pockets (Figure 5a), and if there is infection such as an abscess it should be treated as described below for white line abscesses.

On farms with a high prevalence of shelly hoof, management of the disease can represent a significant challenge because there is currently no evidence available regarding effective control methods. Avoiding routine footbathing, particularly with formalin, would be a good starting point for control given the evidence that these practices are associated with increased prevalence of shelly hoof as described above. Other suggested measures include checking the vitamin/mineral balance of diets, and where possible avoiding walking sheep on stony ground, but it is worth noting that these additional measures are based on suggested risk factors rather than those for which there is an evidence base.

White line abscesses

White line abscesses (often called toe abscesses) can occur secondary to shelly hoof as described above. They can also occur as a primary condition following penetration of the white line by sharp objects such as thorns.

Abscesses present as a hot and painful foot, and pus may burst out at the coronary band (Figure 6). Treatment includes administration of systemic and topical antibiotics and NSAIDs, and where necessary, minimal paring of the sole to ensure drainage of the abscess. Avoiding grazing sheep on areas with thorns helps to prevent abscesses occurring.

Summary of other non-contagious foot diseases

Several other foot diseases may occasionally be encountered, for which further reading on diagnosis and treatment is available in Winter (2004a and 2004b). In summary these conditions include:

- Pedal joint sepsis — results in severe and irreversible damage to the foot and therefore digit amputation is likely to be the only treatment option

- Soil balling — occurs in muddy conditions or when sheep are housed on dirty bedding

- Interdigital hyperplasia — may be hereditary; avoid breeding from affected animals

- Laminitis — occurs as a result of high concentrate diets or concurrent disease (e.g. mastitis, metritis)

- Changes in appearance of hoof horn — these may or may not be pathological and are described in more detail in Box 1.

Conclusions

Granulomas and shelly hoof are present in many UK sheep flocks, and in some flocks are a significant cause of lameness. Avoidance of routine foot trimming and routine footbathing will help to reduce prevalence of granulomas and shelly hoof. This will also aid in management of contagious lameness because farmers will have more time to focus on more effective practices such as prompt treatment of individual lame sheep. There is a need for further research to improve our understanding of the risk factors for shelly hoof, and to provide evidence regarding effective management of this disease.

KEY POINTS

- While less prevalent across all farms, granulomas and shelly hoof occur at high prevalence on certain farms.

- Avoidance of foot trimming and prompt treatment of sheep with footrot and contagious ovine digital dermatitis (CODD) are recommended to reduce prevalence of granulomas.

- Avoidance of routine footbathing may contribute to reducing prevalence of both granulomas and shelly hoof.

- Risk factors for shelly hoof are not fully understood and more research is needed on this disease.