The term ‘iceberg disease’ is now widely used across the ruminant sector. The term itself describes a disease condition identified within a defined population in which for every visible clinical case (the ‘tip’ of the iceberg), there are many others that are either early unrecognised clinical cases, sub-clinically infected or latent carrier animals. In practical terms, when clinical disease is first confirmed, the disease itself is likely to be well established, making control measures problematic, and biosecurity measures imperative. Other general considerations include:

- All have long incubation periods and can easily enter a herd even (as a result of the long periods of latency) those with a structured biosecurity programme

- Laboratory tests are of minimal value during the long latent or sub-clinical phases

- Although the clinical signs described later in this article can be suggestive of sporadic disease incidents in individual goats, a ‘herd problem’ may not be immediately apparent until cases begin to escalate and patterns begin to form

- More than one of these conditions may be active, so a full disease investigation is always advised

- On mixed species units, such as smallholdings and open farms, other species may also be involved — thus any attempt at control should consider this (Figure 1).

- With only around 100 000 goats in the UK, we lack comprehensive surveillance data because of the limited number of laboratory tests undertaken (when compared with similar data from other farming sectors).

The important diseases in goats include caprine arthritis encephalitis (CAE), Johne's disease and caseous lymphadenitis (CLA).

Caprine arthritis encephalitis

Lentivirus is a genus of retroviruses in the family Retroviridae, that causes a group of slowly developing insidious conditions such as CAE and maedi visna (MV) of sheep, the two diseases often referred to collectively as small ruminant lentivirus (SLRV). Although the two viruses cause different clinical presentations in their respective host species, cross species infection can occasionally occur (Shah et al, 2004), and is an important factor in CAE control programmes.

CAE is transmitted predominantly via the ingestion of infected colostrum or milk from infected does. There are, however, many other important routes of infection such as via nose to nose contact and aerosol transfer, via ‘infected milk impacts’ at the teat end in the milking parlour, or through shared use of equipment such as drenching guns or tattooing equipment (Harwood and Mueller, 2018). The practice of feeding pooled colostrum and milk in dairy herds can also lead to increased infection rates as one infected doe can infect the pool, and hence potentially a large number of kids.

Infection induces a strong humoral response, but the antibody produced is not protective — and an infected goat is essentially both virus and antibody positive. The colostrum from infected dams will contain both virus and antibody, the latter affording no maternal protection.

After infection is acquired by whatever route, the virus quickly enters the reticuloendothelial system, carrying virus to target tissues such as the synovial membrane, lung, choroid plexus and udder where virus replication and lymphoproliferation continues.

After initial infection, goats may be asymptomatic for many months or even years before clinical disease is seen. The most common clinical presentations are arthritis and mastitis:

- Arthritis — seen mainly in mature goats aged 12 months and older. The onset may be acute or more slowly developing. All limb joints are susceptible, as is the atlanto-occipital joint. The carpal joint appears to be the most common site, followed by tarsal, stifle and fetlock joint (Smith and Sherman, 2009) (Figure 2). Single or multiple joints may be affected. Most affected joints are enlarged, often visibly, but not always painful and as a further aid to differential diagnosis are rarely ‘hot to the touch’, a sign more suggestive of a bacterial or mycoplasma arthritis. Signs will include obvious lameness, unwillingness to move, increased recumbency with inappetance, and reduced milk production in lactating goats.

- Mastitis — referred to colloquially as ‘hard udder’, CAE infection has been linked to the development of an indurative mastitis (Figure 3) in which the udder tissue becomes firm and shrunken, and milk production from the affected half progressively ceases. The condition is usually insidious in onset and has been the key feature raising a suspicion of CAE in a number of UK commercial dairy goat herds (personal experience).

Less common presentations include:

- Ill-defined weight loss — in individual mature goats (most identified in known CAE positive herds in which other clinical evidence is present)

- Leucoencephalomyelitis — a slowly developing presentation confined to young kids mainly from 1 to 6 months of age. Early signs include incoordination and poor limb placement progressing to paresis, with the hind limbs most affected. This appears to be a rare presentation in the UK.

Presumptive clinical case diagnosis is based on the signs described above and a positive CAE enzyme-linked immuno-sorbent assay (ELISA) test result. Definitive diagnosis can be achieved at post-mortem examination (PME) and histopathological examination of target tissue.

The possibility of new infection should be considered when investigating any group of goats with an increased incidence of ill thrift, particularly if there is evidence of increased lameness as a result of swollen joints, reduced milk yields and udder induration. To pursue a diagnosis of CAE it is recommended to target up to 10 older goats exhibiting clinical signs for serological testing, as infection is usually well established when clinical signs become evident. Disease may also be identified at post-mortem examination of dead/culled goats.

There is no treatment for CAE, and no commercial vaccines. Control is therefore based predominantly on developing a test and cull policy. Determination of the disease prevalence is the first step. Ideally all mature goats in the herd over 12 months of age should be tested using a validated CAE serological test. If this is not financially viable, a proportion of the herd could be tested ensuring that goats of all age groups (over 12 months) are included. Once the level of infection is established an eradication or control programme can be instigated. If the infection is ignored and no control methods are put in place it is likely with time that the infection will lead to significant production losses.

Owners of pet goats will undoubtedly have different aspirations, and although some will wish to be pro-active and take steps to control the disease, others may prefer to live with it. If control is not to be attempted, then on-going advice must be aimed at protecting the welfare of any CAE affected goat and as the disease progresses, then discussing euthanasia on humane grounds as a final option.

Heat treating or pasteurising has reportedly been a useful supportive measure in any control programme. Milk or colostrum is held at 56°C for 60 minutes; commercial pasteurisers are available.

The British Goat Society (BGS) runs a voluntary Monitored Herd Scheme for those goat owners attending BGS shows with their goats (BGS, n.d.). A more structured accreditation scheme is facilitated by Scotland's Rural College (SRUC, n.d.).

Johne's disease

Johne's disease, which is more commonly associated with cattle and to a lesser extent sheep, can also cause disease in goats. Mycobacterium avium subsp paratuberculosis (MAP) is the causative organism. There are specific cattle and sheep isolates, with most goat infections identified as cattle strains. New infection can be introduced into a herd from purchased goats, from infected cattle or sheep kept together, or from faecal contamination of their environment. The disease is not only encountered in intensively kept goats, and the author has confirmed outbreaks in Pygmy goats kept on a smallholding and on an open farm.

Infection is mainly transmitted to young kids <6 months old (Smith and Sherman, 2009), following ingestion of feed or water supplies contaminated with MAP-infected faecal material and potentially from faeces contaminated teats while suckling. Pooled colostrum can also readily transmit new infection to a wider group of susceptible kids (as with CAE). There is also confirmed intra-uterine infection of kids, from dams that are heavily infected in late pregnancy (Manning et al, 2003). Goats >6 months of age become progressively more resistant to new infection, although lateral spread even in adult goats may occur if the environment becomes heavily infected, particularly in housed commercial herds. This susceptibility in adults is more likely if their immune system is compromised because of, for example, generalised debility or as a result of other concurrent disease or injury.

Once infected, there is then an extended incubation period or latency during which no clinical disease will be evident, but the goat may be shedding MAP in their faeces, thus adding to the environmental challenge. Depending on a number of largely unknown host/pathogen factors, the next stages of clinical disease will vary in timescale, although it seems likely that if allowed to ‘live out their lives’ many if not all goats would progress to these later clinical stages of disease. Although not proven, it may well be that in some individuals, infection may be controlled with the goat becoming resistant to the infection and hence with no further shedding or clinical disease. In others, however, the infection progresses to intermittent shedding and sub-clinical disease or eventually becomes clinical with heavy environmental shedding. In an endemically infected herd, it is likely that each of these disease presentations are present, thus further complicating its control, and confirming its aetiopathogenesis as an ‘iceberg disease’.

When clinical signs develop, these may be as early as12 months of age, but more commonly from around 2.5 years old. The stimulus for clinical signs to develop is still poorly understood but may be linked additionally to stressful incidents such as kidding, transportation, poor nutrition or concurrent disease such as endoparasitism.

Early clinical signs may be subtle, including progressive weight loss and reduction in milk yield if lactating, with appetite often unaffected. As the condition develops, anaemia and a lack-lustre coat may become apparent together with sub-mandibular oedema (a result of the progressive hypoalbuminaemia) (Smith and Sherman, 2009). The diarrhoea associated with disease in cattle is not a feature of the condition in goats until the terminal stages.

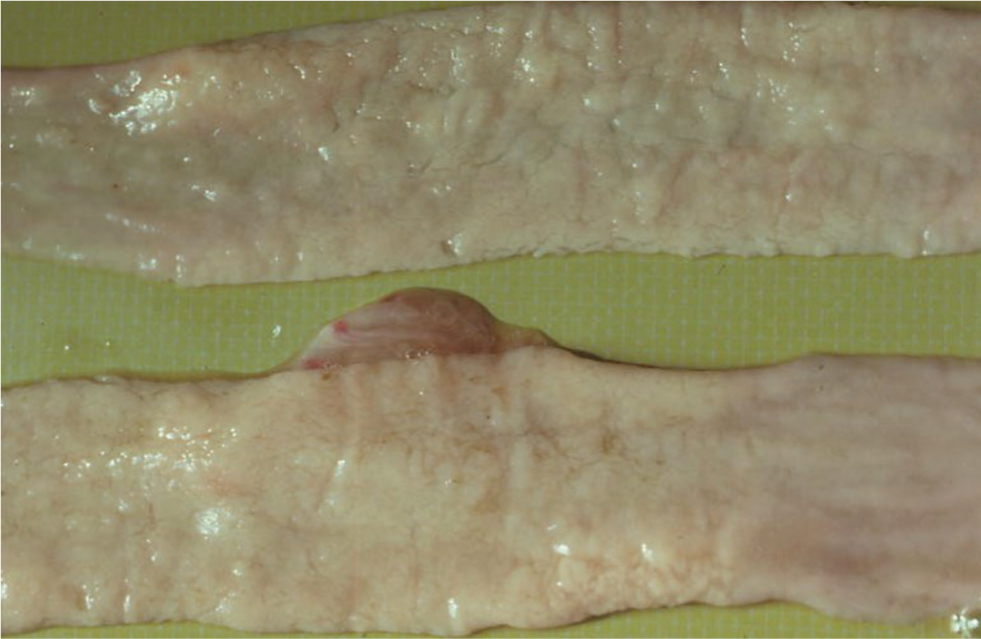

Confirmation of infection in live clinical cases can be achieved by a combination of a serum ELISA test, and examination of faeces for MAP by microscopic examination of Ziehl Neelsen smears or by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Definitive diagnosis is by gross PME, supportive laboratory testing and histopathology. The gut changes are more subtle than those seen in cattle, and segmental gut thickening may only be identified by gentle palpation along the gut length between finger and thumb (Figure 4). Mesenteric lymph nodes may be grossly enlarged and oedematous, with caseation and even calcification being a feature of later stage infections (Figure 5).

During the long period of latency most available tests are ineffective; there will be little if any humoral response detectable, and the sporadic shedding of organisms in faeces may be below detectable limits.

A combination of the long period of latency and a lack of effective tests during this period make control problematic and can compromise biosecurity when purchasing new stock. The aspirations of the owner may also be very different, and whereas eradication by testing and culling may be the goal in a commercial herd, it may not be the same for the owner of beloved pet goats.

If attempted, then eradication may be achieved over several years, but will need considerable commitment by the herd owner and attending veterinarian. It is based on regular whole herd testing using serology and faecal monitoring, with culling of testpositive goats and offspring, accreditation schemes are available.

Such a control programme must be supported by:

- Prompt identification and removal of clinical cases

- Minimising faecal contamination of feed and bedding — particularly for young kids

- Snatching kids at birth and rearing away from adults

- Feeding colostrum from test-negative dams, possibly combined with pasteurisation, and avoiding the use of pooled colostrum

- Culling kids born to does developing disease or becoming test positive in late pregnancy (because of risk of in-utero infection).

The Gudair Johne's vaccine has a marketing authorisation for use in goats and is used successfully in some infected herds as part of their on-farm Johne's control programme.

Caseous lymphadenitis

CLA is a chronic bacterial infection resulting in superficial and visceral lymphadenopathy caused by Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis. The condition affects both goats and sheep, and is an important disease when both species are kept together.

Infection gains access mainly through wounds or small breaks in the skin and mucous membrane, but occasionally in heavy infections by inhalation into the lung tissue and associated lymph nodes (particularly in housed commercial herds). Organisms are carried to regional lymph nodes, in which they can remain apparently in a protected environment, resisting normal host immune mechanisms. The incubation period from infection to the time superficial lymph node enlargement as a result of abscess formation becomes clinically apparent may be up to 6 months, although 2–3 months is more typical (Ashfaq and Campbell, 1980) — and yet again compromises biosecurity when introducing new stock.

In many affected goats, there is little or no impact on their general health and productivity, because typically it is only the superficial lymph nodes that are affected, although these are unsightly. The most common superficial nodes are parotid, sub-mandibular and prescapular — reflecting the greater likelihood of superficial trauma in the areas these nodes provide drainage to (Figure 6). Infected lesions in the hind limbs will lead to popliteal lymph node enlargement, and damage to the skin of the udder and teats may cause enlargement of the supramammary node. If infection levels in the herd increases, however, then abscess formation becomes more widespread, internal organs and lymph nodes are affected, and clinical signs will vary depending on the site of bacterial multiplication.

These superficial abscesses may rupture and drain spontaneously or, if prominent, may as a result of mechanical insult. It is important to emphasise the fact that once infected, a goat will probably never be free of infection, even if a lymph node has become enlarged, has ruptured and apparently healed — disease can theoretically flare up at any stage.

The presence of one or more superficial swellings anatomically linked to a lymph node should always raise a strong suspicion of CLA. For laboratory examination, a sample of the abscess pus should be submitted for bacterial culture: if an abscess is burst, then a swab inserted into the abscess and ‘rubbed over the abscess capsule’ is ideal, although there is a greater chance of contaminating bacterial overgrowth. If no burst abscesses are available, then after shaving and sterilising the skin surface, a wide bore needle can be inserted into the abscess and pus aspirated, although this may be very thick. Culturing C. pseudotuberculosis will confirm the diagnosis. It is important while waiting for results that any goats with discharging abscesses (including any that are subjected to needle biopsy) are isolated to minimise spread. Serological tests are now available, and are being used to manage outbreaks, although false negative results in early infection can be problematic, and apparent false positive results have also been reported in goats.

Treatment of individual goats of economic or sentimental value can be attempted but is of questionable value as a tool for ongoing control in such infected herds. There are two approaches: either surgical or using antibiotic (or a combination of the two). Allowing the abscesses to mature and burst naturally is to be discouraged, as the leaking pus can contaminate the building fixtures and fittings (such as feed troughs) on which the organism can survive for up to 10 weeks, (and up to 6 months in contaminated soil) (Brown and Ollander, 1987). Because of the potential zoonotic risk, protective gloves should always be worn.

Antibiotic treatment of infected goats has been attempted, but can give disappointing results, mainly because antibiotics cannot penetrate into the centre of abscesses in which the organism is essentially protected by the thick pus generated.

Control of the infection in infected commercial herds is based on identification of infected goats by clinical evidence of abscess formation, or positive serology, and a strict culling policy. This approach has been reportedly successful. Attention should be paid to possible environmental insults predisposing to new infections such as projecting nails, barbed wire, gate hinges etc. Ectoparasitic infestations should be controlled — they will predispose to rubbing, which in turn can lead to damage to the skin integrity allowing the causative bacteria to enter the goat. As the organism is so resistant in the environment, this can have an adverse effect on any attempts to control infection by segregating known infected from ‘clean’ goats. Infection can be readily transferred from one group to another on weigh crates, hurdles, feed troughs and in the milking parlour — thorough cleaning and disinfection with an approved disinfectant should be undertaken regularly, including shearing equipment in fibre herds.

Biosecurity summary

Purchase from accredited or known disease negative herds where possible.

- CAE — blood sample all incoming goats. The CAE ELISA test in goats over 6 months has high sensitivity and specificity

- Johne's disease — the Johne's ELISA test will not identify latent infection, and the PCR test may not identify low levels of excretion, therefore purchasing from accredited or known negative herds is always advisable

- CLA — all incoming goats should be examined for evidence of enlarged lymph nodes while in quarantine, and an effective quarantine period for this disease should be 2–3 months minimum — and much longer if practicable (Harwood personal view). Serological screening of incoming goats is a further tool, although false negative results are a problem in the early stages — where possible purchases are made only from herds where no clinical disease has been recorded.

Conclusion

Controlling iceberg diseases in goats can be problematic and require an understanding of routes of infection, available laboratory tests, clinical signs, vaccination, and other control measures that may involve test and cull programmes. These factors need to be considered alongside the aims, objectives, and aspirations of individual goat owners and these can vary considerably depending on why goats are kept.

KEY POINTS

- As with other ruminants, goats can be affected by a group of diseases referred to as iceberg diseases, these include caprine arthritis encephalitis (CAE), Johne's disease and caseous lymphadenitis (CLA).

- Goats are kept for many reasons in the UK, the aspirations regarding control measures may be very different between owners of beloved pet goats and a large commercial dairy goat unit.

- Biosecurity is of paramount importance, with emphasis placed on keeping all goat holdings free of these diseases.

- Currently available laboratory tests often give low specificity particularly in those diseases with a long period of latency such as Johne's disease.

- Control can be particularly problematic on hobby smallholdings where goats are kept with, for example, sheep as any successful control programme should consider both species together.