The ability to perform a thorough, detailed clinical examination is a key skill for any veterinary surgeon. This article discusses an approach to the examination of the individual ram or ewe from arrival on farm through to completion of the clinical examination.

Arrival on farm

Personal protective equipment is required; typically consisting of disinfectable wellington boots (with the option of steel toe capped variants available), waterproof trousers and top (the author prefers KiwiKit for its durability, neoprene sleeves on the top and padded knees on the trousers) plus a boiler suit if desired. Personal protective equipment should be freshly laundered, new or be disinfected on arrival at the farm (the author recommends FAM30 (Evans Vanodine) as an iodophor disinfectant with bactericidal, viricidal and fungicidal properties at a 1:49 dilution (Evans Vanodine, 2022)), the exception to this is if tuberculosis is suspected, when a 1:14 dilution should be used (DEFRA, 2024). Vets should be aware of, and advise farmers, that this higher concentration came into effect in March 2024, and replaces the old dilution rate of 1:20. Nitrile or latex gloves should be worn in all scenarios.

After donning appropriate personal protective equipment and disinfecting as required, basic equipment for clinical examination should be gathered (Table 1). It is a good idea to use an easily cleanable weatherproof container to store this in when on farm to avoid environmental contamination.

Table 1. What equipment do I need?

| Item | Reason |

|---|---|

| Stethoscope | Auscultation |

| Digital thermometer | Assess rectal temperature |

| Nitrile gloves (more than one pair) | Biosecurity and protection from zoonoses |

| Arm length rectal gloves | Reproductive tract examination |

| Mobile phone (in an easy to disinfect case) | Torch function for pupillary light reflex |

| Camera to photograph any clinical abnormalities | |

| Call experienced colleagues for advice or report suspicion of a notifiable disease to Animal Plant and Health Agency | |

| Headtorch | Improve vision if out of hours or limited lighting |

| Can be used for pupillary light reflex | |

| Scalpel blade | Skin scrapes |

| Needle and syringes | Venepuncture and aspirate masses |

| Serum, EDTA, lithium heparin blood tubes | Sample collection |

| Penside beta-hydroxybutyrate (BHB) test (e.g Centrivet GK blood glucose + ketone meter, Rapid Labs) | Patient side assessment of BHBs for pregnancy toxaemia |

| Plain sample pots | Collect dermatological samples |

| Collect faecal samples | |

| FAM30 + bucket + brush (clean water source required or 5-litre drum of clean water) | Disinfection of self and personal protective equipment |

The ‘hands-on’ part of the clinical examination is usually the final part of the information gathering stage of the farm animal visit, to then be followed by sample collection (as required) and information giving (presenting differential diagnosis to the client and treatment plans, plus population advice). Before reaching the hands-on part, practitioners must ensure that they understand the presenting complaint and have taken a detailed flock level and individual history.

A note regarding clinical examination at the veterinary practice

Many practices also provide facilities to perform the clinical examination of individual, or small numbers of, sheep at the practice. This can provide a reduced cost service for clients (with either a reduced, or no, visit charge applied) as well as allowing practitioners to examine and treat more animals in a short space of time, something of particular use during busy lambing seasons. Where sheep are brought to the practice, any examination tables, equipment and the floors of examination rooms should be adequately disinfected between clients.

The personal protective equipment and other equipment required remains the same and the author would recommend the same approach to the ovine clinical examination on farm or at the practice. Distant examination can still be performed either in the client's trailer or in the pens at the practice.

Distant examination (‘over the farm gate’)

The individual should be assessed before entering the pen or shed they are in. This will allow a more accurate assessment of:

- Demeanour

- Locomotion

- Circling (also evidenced by straw/bedding patterns)

- Head tilts or turns

- Ataxia

- Separation from the flock.

Restraint

Hands-on clinical examination should only be performed with the animal adequately restrained. This could be:

- On a halter (Figure 1)

- In a pen with an assistant holding (manual restraint) (Figures 2and3)

- In a turnover crate (the least ideal)

- In a sheep crush.

The author does not recommend the use of a sheep race unless there are no other options as access to the flanks and ventral aspect is restricted in this situation.

The hands-on clinical examination

Several different approaches to the hands-on clinical exam of ruminants are described, including nose-to-tail, systems based and tail-to-head (Jackson and Cockcroft, 2002; Lovatt, 2010; Nelson et al, 2022). The approach used remains the practitioner's choice and a system that the individual practitioner is familiar with and covers all aspects is the best choice.

Whichever approach is chosen, practitioners should ensure that they examine the entire animal, consider flock-based patterns and be mindful not to fall into the trap of ‘problem-based examination’, where one presenting sign biases the diagnosis at the detriment of a thorough, full clinical examination (Jackson and Cockcroft, 2002). An example of this would be the presentation of a sheep with a dog bite wound to the left hindlimb, which may distract from the requirement to assess mucous membranes, capillary refill time and other parameters that may indicate hypovolaemic shock.

The author's preferred approach to ensure a thorough approach to the hands on portion of the ovine clinical exam is set out in Table 2 and this order is used to structure the rest of this article.

Table 2. Numerical order for hands-on ovine clinical examination

| Body area | Numerical order |

|---|---|

| Body condition score | 1 |

| Head, neck and oral cavity | 2 |

| Left thorax | 3 |

| Right thorax | 4 |

| Left abdomen | 5 |

| Right abdomen | 6 |

| Perineal region | 7 |

| Rectal temperature | 8 |

| Vaginal examination and udder (females) | =9 |

| External genitalia (males) | =9 |

| Fore and hind limbs | 10 |

| Feet | 11 (easiest done when tipped for stages 9 and 10) |

| (Full neurological examination (if indicated)) | 12 |

Table 3 outlines the core parameters and reference ranges (Lovatt, 2010; Scott, 2015; Merck, 2016), while the text sections for each area from Table 2 discuss specifics in terms of approach and areas to examine. Unlike in dairy cattle, rumen score/fill is an unreliable and subjective parameter and the author does not routinely recommend its use as part of a clinical examination (Munoz et al, 2018).

Table 3. Reference ranges for core parameters in the ovine clinical examination*

| Parameter | Target range | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Heart rate (resting) | 70–80 bpm | A level of elevation may be expected in the manually restrained animal as a result of handling stress |

| Respiratory rate (resting) | 12–20 bpm | |

| Mucous membrane | Salmon pink and tacky | (FAMACHA of ocular mucous membranes useful) |

| Capillary refill time | ≤2 seconds | |

| Rumen turnover rate | Three turnovers in 2 minutes | |

| Perineal staining score (Dag score) | ≤2 | (Munoz et al, 2018; Signet Breeding Services, 2022) |

| Rectal temperature | 38.5–40.0°C | |

| Mobility score | 0–1 | Warwick scale 0 (normal) – 6 (unable to stand or move) (Kaler et al, 2009) |

Body condition score

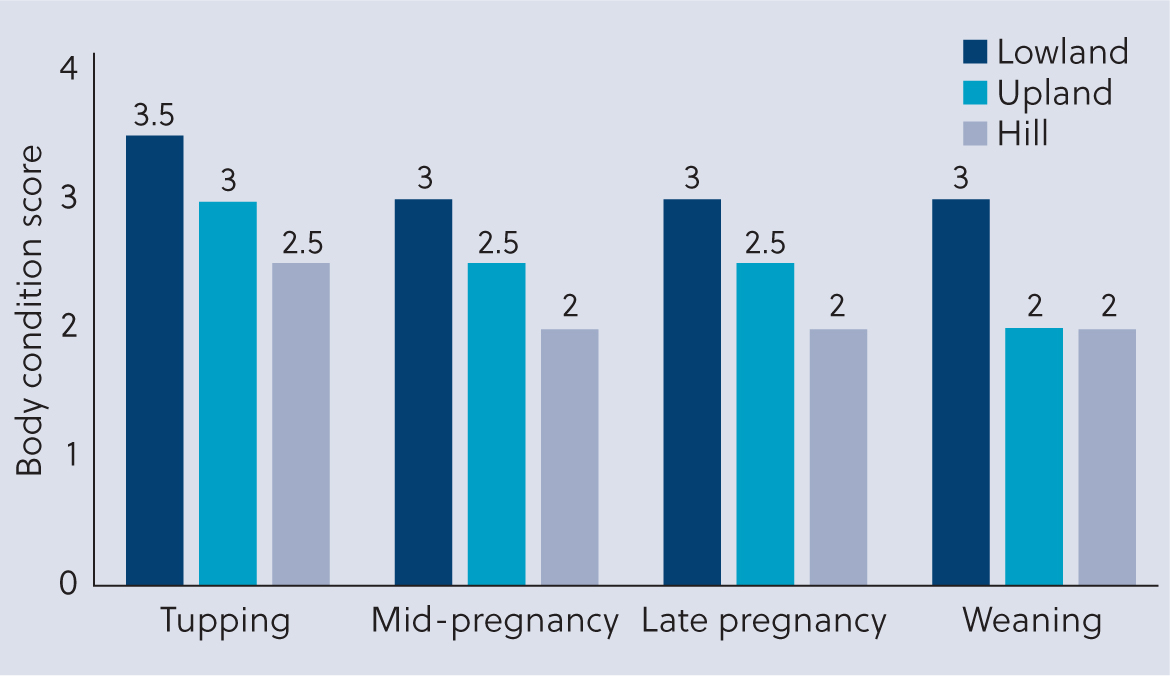

Body condition score cannot be reliably performed without physical contact with the animal, although significant emaciation can be identified even in a fully fleece sheep (body condition score ≤1). Target body condition score for ewes at different stages of production are noted in Figure 4 alongside variation between systems. Figure 5 shows a handling system allowing effective assessment of body condition score by palpating the coverage over the vertical and transverse processes of the lumbar spine.

Head, neck and oral cavity

Examination of the head should include assessment of the eyes as indicators of dehydration and anaemia (FAMACHA test for Haemonchus contortus or less commonly advanced fascioliasis). Pupillary light reflex and menace can be assessed if required. Any discharge or ocular changes should also be assessed.

The submandibular and parotid lymph nodes can be palpated and assessment of submandibular oedema (‘pitting’ oedema) suggestive of chronic endoparasitism is usually done at this point. Airflow can be assessed by placing wool or straw in front of the nostrils.

Intra-oral examination should be performed and gags can be used for safe examination. Assessment of the oral cavity can indicate lesions of the oral mucosa (foot and mouth disease, Bluetongue virus, ‘oral orf’) (World Office of Animal Health, 2018) (Figure 6), and allow examination for molar abscesses and oesophageal obstructions (choke). The eruption of incisors is used to estimate age (Table 4).

Table 4. Ovine permanent tooth eruption and corresponding age in months

| Teeth eruption | Approximate age |

|---|---|

| Incisor 1 (central pair) | 1–1.5 years |

| Incisor 2 | 1.5–2 years |

| Incisor 3 | 2–2.5 years |

| Incisor 4 | 2.5–3.5 years |

| Premolars | 1.5–2 years |

| Molar 1 | 3 months |

| Molar 2 | 1 year |

| Molar 3 | 1.5–2 years |

The neck should be examined for lesions and abscesses (e.g injection site or drench gun-related abscesses), and range of lateral and dorsoventral motion can be assessed through manipulation of the neck. Auscultation of the cervical trachea is possible along the ventral neck and thoracic inlet.

Thorax

Auscultation of lung fields on both sides should be performed in the dorsal, mid and ventral thirds of the lung field. Auscultation of the heart for rate and rhythm is performed bilaterally, noting that on the right hand side the olecranon lies just cranial to the right atrioventricular valve (yellow region in Figure 7), and on the left hand side the left atrioventricular valve is at the level of the elbow, with the pulmonic below and aortic valve above the elbow. Wool should be parted to maximise contact between the diaphragm of the stethoscope and the body wall.

If there is concern about the ventral thorax (e.g brisket sores) then the animal can be ‘tipped’ to allow visualisation of the ventral body wall (Figure 8), but this is often best done towards the end when assessing stages 9 (udder (female) or external genitalia (male)).

More specific tests such as thoracic ultrasonography or the ‘wheelbarrow’ test for jaagsiekte can be performed if clinical suspicion is raised (Scott, 2011).

Abdomen

Auscultation of the rumen, coupled with ballottement and palpation, should be performed on the left hand side, remembering that bloat is commonly observed and palpated over the left hand side. Ballottement of the ventral abdomen can be used in late gestation to feel lambs but is not 100% reliable for a pregnancy diagnosis. Auscultation and palpation of the right hand side is also performed for further assessment of the gastrointestinal tract.

Perineal area and rectal examination

Excessive perineal staining (‘dag’ score ≥2) (Munoz et al, 2018) can be indicative of scours (infectious, nutritional or parasitic) and can also be an indicator of increased ectoparasite risk (Lucilia sericata).

Assessment of rectal temperature requires due care and attention to ensure the thermometer is making contact with the rectal mucosa and not with faecal content. Faecal consistency can also be assessed with a sample collected rectally if required.

Vaginal examination and udder

Vaginal examination is especially important in the peri-parturient period. In the days post lambing, arm-length gloves should be worn for vaginal examination, especially in the peri-parturient period when infectious abortion rises up the differential list with its zoonotic potential.

Care should be taken to avoid any trauma to the soft tissues of the reproductive tract and assessment can easily be made of active abortions, stage 1 or 2 labour, incomplete cervical dilation, retained fetal membranes, undelivered lambs (a common cause of the ewe that rapidly goes downhill 6–24 hours post lambing), metritis and vaginal or uterine tears. Practitioners should be aware that normal lochia can be observed up to 3 weeks post-partum (Srinivas and Sreenu, 2009; Gahlot et al, 2017). Assessment of any prolapses should form part of the vaginal exam.

The ewe is best then tipped for examination of the udder (Figure 8). There are no validated systems for scoring the udder, so palpation for abnormalities, tenderness, erythema or heat remain the best measures of assessment for mastitis. In lactation, milk can be expressed and sent for culture and sensitivity testing.

A lack of milk letdown in the first few hours often presents as pain on palpation, swollen teats, empty lambs and no milk expressible. This can be treated with 10 iu oxytocin (single dose, Oxytocin-S, MSD Animal Health, 0 milk withhold) repeated as necessary and accompanied by regular stripping out (National Office of Animal Health, 2022). The author notes that some practitioners question the efficacy of oxytocin in sheep compared to cattle, but a previous study by the author (Charles and Stockton, 2022), involving 209 ewes, showed that many practitioners throughout the UK and Ireland use oxytocin with significant success rates in sheep during obstetric procedures and to assist with uterine involution, retained fetal membranes and poor milk letdown.

Shearing injuries to the udder and teat unfortunately remain relatively common.

Limbs

While tipped, fore and hind limbs can be assessed using the SAP and SPIRM approach for long bones and joints respectively (Table 5).

Table 5. SAP and SPIRM mnemonics for the assessment of long bones and joints

| Joints | Long bones |

|---|---|

| Swelling or effusion | Swelling |

| Pain on movement/manipulation | Atrophy of muscle |

| Instability (varus/valgus) | Pain |

| Range of motion | |

| Manipulation |

Feet

While tipped, the feet can be assessed for any obvious lesions or causes of lameness (Table 6, Figure 8) (Winters and Clarkson, 2012; MSD, 2020).

Table 6. Common causes of ovine lameness and their prevalence

| Cause | Prevalence (MSD, 2020) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Footrot | 43% | Interdigital space extending to underrun the sole horn and outerwall |

| Scald (ovine interdigital dermatitis) | 38% | Interdigital space |

| Contagious ovine digital dermatitis | 12% | Coronary band extending dorsoventrally along the hoof capsule |

| Shelly hoof | 3% | White line |

| Toe granuloma | 1% | Toe tip/erupting from underneath sole horn |

| Other | 3% | Variable |

Ram-specific considerations

Assessment of the external genitalia of the ram is best done in the tipped position (Figures 9 and 10). This allows for palpation and measurement of the testicles within the scrotum, palpation of the spermatic cords, examination of the prepuce alongside extrusion of the distal penis and examination of the vermiform appendage (particularly usefully in cases of urolithiasis). Epididymitis, orchitis and testicular hypoplasia are all readily identifiable on palpation. Preputial strictures, penile conformational abnormalities or trauma may all be causes attributable to the inability to extrude the penis fully. Rams should have a body condition score of 3.5–4.0 ahead of mating season as 16% of bodyweight can be lost through the breeding season, and a body condition score of 3.0 is recommended in winter (Farm Advisory Service, 2020).

Before mating, all breeding males should undergo a check up (Table 7) (Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board, 2020) and pre-breeding examination, with as many as 21% being deemed ‘unsuitable for breeding’ at these examinations (Price, 2021). Detailed discussion of the ram pre-breeding examination is beyond the scope of this article, but thorough guidance can be found through the Sheep Veterinary Society website (Sheep Veterinary Society, 2014).

Table 7. The 5 Ts of the ram MOT

| Area | Notes |

|---|---|

| Teeth | Genetic abnormalities (prognathia or brachygnathia) |

| Broken mouthed? | |

| Molar abscesses? | |

| Toes | Assess locomotion, arthritis and foot conditions |

| Testicles | ‘Ripe tomato/flexed bicep’ firmness, assess for any lumps, bumps or swelling that may indicate orchitis or epididymitis Scrotal circumference minimum standards vary by age |

| Tone | Body condition score of 3.5–4.0 |

| Treatment | Rams should be treated for ailments and included as part of the flock vaccination protocol before mixing with the ewes Parasite treatment and faecal egg count assessment is recommended before introducing to pasture with the ewes |

Lamb-specific considerations

The history of the individual and the group is especially important during the clinical examination of neonatal lambs, with many problems identified in the individual suggesting that the entire lamb crop may be at risk (e.g failure of passive transfer indicating a flock-wide nutrition and colostrum problem, or an infectious disease outbreak or abortion storm). Data records are especially important at this time, remembering that targets are <2% abortions and <5% lamb losses birth to 24 hours and <5% 24 hours–7 weeks (Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board, 2016; Farm Advisory Service, 2020).

The age of the lambs affected is important to ascertain when considering lambs aged 0–24 hours and 1–4 weeks; the differentials may be very different.

Clinical examination of the neonatal lamb should follow a similar systematic approach to ensure an all-encompassing clinical examination. However, specific attention should be drawn to the following:

- The umbilicus: umbilical hernia? Navel ill (omphalitis)? Iodine treated to dry up? Umbilical remnant?

- Joints: specific attention here needs to be given for early onset joint ill or fused joints.

- Hypothermic indicators: tucked up or hunched lambs? Colloquially known as ‘standing on a teaspoon’

- Neurological or neuromuscular changes: head turn/tilt, spastic paralysis and intention tremors are all important differentials for trace element deficiencies and infectious diseases (border disease, cerebrocortical necrosis 11)

- Mouth: ensure a strong suck reflex and no excessive salivation, which could indicate ‘watery mouth’. Ensure no prognathia, brachygnathia or cleft palate

- Rectal temperature: <37°C indicative of hypothermia and intervention required, <32°C indicates severe hypothermia. Some of the core parameters have different reference ranges because of the different metabolic rate and surface:volume ratios of neonates compared to adult sheep (Table 8) (Jackson and Cockcroft, 2002; Merck, 2016).

Table 8. Core parameters and reference ranges for neonatal lambs

| Parameter | Target range (neonates) |

|---|---|

| Heart rate (resting) | 80–100 bpm |

| Respiratory rate (resting) | 30–40 bpm |

| Mucous membrane (eye or buccal cavity) | Salmon pink and tacky |

| Capillary refill time | ≤2 seconds |

| Skin tent time | <3 seconds, >5 seconds indicative of dehydration |

| Rumen turnover rate | N/A |

| Perineal staining score (Dag score) | ≤2 |

| Rectal temperature | 38.5–40.0°C (ensure patent anus and rectum) |

| Skull | Without crepitus on palpation |

| Eyelids | Normally turned out (entropion common in lambs) |

Conclusions

The ability to perform a thorough ovine clinical examination is a fundamental ‘day one’ skill for veterinary professionals. By following a systematic approach such as the one outlined in this article practitioners can ensure that a full examination is performed to provide as much diagnostic information as possible. As ever, appropriate personal protective equipment, biosecurity measures and restraint should be used before starting the examination. A thorough history should be taken alongside the clinical examination to provide a complete picture, as well as performing ‘over the farm gate’ or ‘distant’ examination of the group or flock.

KEY POINTS

- Ovine clinical examination is a key skill of any production animal (or mixed animal) practitioner, which can yield a vast amount of information when performed correctly.

- A thorough clinical examination should include ‘hands off’ examination and follow a detailed history taking.

- While there are many approaches, practitioners should ensure they use a systematic approach that they are familiar with to avoid incomplete examination.

- Particular nuances should be considering when interpreting the clinical examination of the rams and neonatal lambs.

- Ensuring appropriate restraint and biosecurity is essential before commencing ovine clinical examination.