Fertility testing of newly purchased rams is a safeguard of investment, and testing existing rams before mating identifies subfertile and infertile rams, allowing them to be removed from the farm. Fertility testing is crucial for single sire mating groups. Single sire mating is becoming increasingly common as more farms look to breed their own replacements and use selective breeding to improve their flock. On farms where rams are used together, in groups of two or more, and pre-breeding examinations are not carried out, a ram could be purchased for a potentially large sum and may be kept for several breeding seasons without ever leaving a lamb. This is costly and inefficient.

Pre-breeding examinations of 280 rams, across 5 practices, showed that 16% were unsuitable for breeding (Lovatt et al, 2016). Major abnormalities included abnormalities to feet (17.6%), teeth (12.7%), and rest of body (5.5%). Reproductive abnormalities included abnormalities to the penis (1.9%), scrotum (3.9%) and prepuce (1.1%). The study also found 7.6% of testicles were too soft and 5.25% were too small.

Fertility testing is a valuable management practice and also provides vets with a good opportunity to examine the ram group: for example to assess lameness prevalence, body condition and discuss ram selection. Barr (1984) showed that routine pre-breeding examination of all rams on a farm for 5 years increased the lamb crop by 2.7%.

Fertility testing aims to improve production efficiency and reduce costs by only keeping and using rams that are fertile and fit for purpose. Ideally, rams should be semen tested at least 2 months pre-mating (Boundy, 1993). This allows sufficient time to correct any body condition issues, lameness issues and retest any failures, allowing for the 6 weeks taken for sperm production. It also allows time to source any replacement rams, should they be required. When undertaking pre-breeding examinations for early lambing flocks, consider that rams examined out of season will potentially have substantially reduced size and weight of the testicles, and reduced sperm production (Boundy, 1993). Treatment of rams with melatonin implants can increase scrotal diameters and testicular volumes, and therefore increase the fertility of rams out-of-season (Cevik et al, 2017), allowing for early season breeding.

General examination

Examination of each ram should be carried out and the findings should be recorded. The Sheep Vet Society (SVS) provides a useful template ‘Pre-breeding examination on farm data collection form’ (SVS (2014a)). A reasonably comprehensive examination can be carried out quite quickly by adopting a nose-to-tail approach. Examination should include the following:

Dentition

Check the incisors; do they meet the dental pad or is the ram undershot or overshot, and are there any incisors missing? Check the molars by palpating the jaw; are there any missing molars, abscesses or other abnormalities palpable within the jaw?

Neck

Check the neck area for abscesses associated with caseous lymphadenitis (CLA). Abscesses can appear as 3–6 cm firm masses in the superficial lymph nodes. Check the submandibular, parotid and prescapular regions in particular and any suspicious abscesses should be sampled; take a sample of pus or swab an open lesion (Gascoigne et al, 2020).

Brisket

Palpate the brisket for sores. Lovatt et al (2016) demonstrated that 5.4% of rams at a pre-breeding examination had a brisket sore. Brisket sores are associated with general health abnormalities of rams that affect reproductive performance, for example, lame rams spend more time lying down and are therefore seen with brisket sores. It is advisable that rams with brisket sores are not put in a harness or raddle. Suitability for breeding should be seriously considered, as mating has the potential to further traumatise a brisket lesion.

Condition

Body condition score (BCS) the ram on a scale of 1 (emaciated) to 5 (obese) (Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board (AHDB), 2018). Rams should be body condition score 3.5 at mating (Vipond and Morgan, 2010). Although some guidelines suggest 3.5-4.0 is acceptable, the authors' believe this is too high. It takes 6–8 weeks to gain one BCS if on high quality grass (AHDB, 2018). Ideally, rams should be condition scored in plenty of time and feeding adjusted accordingly. Rams that are in optimal condition 10 weeks before mating should continue to be fed good quality grass. Those that are below optimal body condition should receive supplementary feeding, for example 0.5 kg concentrates at 16% crude protein per day, introduced slowly. BCS can be used as a selection criteria, allowing rams that maintain condition within a system to be retained and propagate these successful genetics. Any rams significantly below BCS target, should be fully examined and investigated; poor condition may be a sign of poor dentition or diseases such as liver fluke, Johne's or other ‘iceberg’ diseases (AHDB, 2019). Overfat rams can also be a problem at mating; fat is insulating so increases testicular temperature resulting in reduced testosterone levels, which reduces both libido and sperm quality (Fourie et al, 2004).

Legs

Observe limb conformation; abnormalities such as straight hocks or sloping pasterns will reduce the ram's working life (Vipond and Greig, 2007; Greig, 2007). Reduced longevity increases ram cost per lamb born, demonstrated in Table 1.

| Life span of ram (years) | No of ewes put to ram (selling at 150%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 40 | 60 | 80 | 100 | |

| 1 | £11.82 | £7.88 | £5.91 | £4.73 |

| 2 | £5.91 | £3.94 | £2.96 | £2.37 |

| 3 | £3.90 | £2.63 | £1.97 | £1.58 |

| 4 | £2.96 | £1.97 | £1.48 | £1.18 |

Feet

Rams need to be turned over to properly examine all four feet for signs of interdigital granulomas, toe granulomas, footrot, contagious ovine digital dermatitis (CODD) or scald. Feet should also be assessed for conformational abnormalities. Lovatt et al (2016) demonstrated that 17.6% of rams presented for a pre-breeding examination had foot abnormalities. Poor limb or foot conformation should be recorded and discussed; not only are these abnormalities potentially genetic but they may also impact the longevity of a ram. The author finds that turning the ram is best done after semen collection to prevent difficulties obtaining a sample as a result of the stress of casting.

Reproductive examination

Conventionally, the reproductive examination is performed first, followed by semen sampling. In the authors' experience, examination stresses the ram just before sampling and he is therefore less likely to produce a semen sample. It is therefore preferable that semen analysis is performed prior to reproductive examination in the authors' experience.

Reproductive examination can be carried out with the ram standing or with the ram cast and should include the following:

Testicles

Testicles should be smooth, firm like a ripe plum or flexed bicep and of equal size when palpated. Both testicles should move freely in the scrotum (Figure 1). Scrotal circumference should be measured at the widest part; see Table 2 for suggested minimum scrotal circumference measurements (Figure 2). Use of a scrotal tape measure allows for consistency when measuring scrotal circumference. Scrotal circumference is an important metric as it correlates directly with capacity for sperm production (Wahyudi et al, 2022). The risk with small testicles is that sperm production will be insufficient for serving an appropriate number of ewes. This is particularly important in sheep due to the compact breeding season, during which time rams are expected to serve a significant number of ewes. The authors' observe the highest incidence of testicular hypoplasia in Beltex rams.

| Ram lamb (<1 year old) | Shearling ram (1–2 years old) | Mature ram (>2 years old) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Down or longwool | 30cm | 32cm | 36cm |

| Hill breeds | 28cm | 30cm | 34cm |

Sheep veterinary society ram fertility workshop, Edinburgh, 2014)

Epididymis

The epididymis should feel slightly firmer than the testicles. Palpate to check for lumps, heat, pain, swelling or asymmetry (Figure 3). Epididymitis of the head, characterised by a hardened thickening, is a common finding (Scott, 2015).

Spermatic cords

Palpate cords carefully for masses; abscesses and varicoceles which can affect spermatic cords.

Scrotum

The scrotum should be clean with no evidence of chorioptic mange; scrotal mange can heat the testicles. Woolly scrotums are often queried by clients as a cause of testicular overheating, but there is limited evidence that this is a concern (Fthenakis et al, 2001).

Penis and prepuce

The prepuce and penis should be examined for any signs of disease or trauma. A very floppy prepuce may reduce mating ability. The penis should be extruded and examined for signs of disease such as balanitis (Figure 4), or an abnormal or missing urethral process. A missing urethral process in itself may not reduce fertility but in a newly purchased ram, may be a sign of a previous episode of urolithiasis. Extruding a ram's penis can either be achieved with him standing or with him cast, with one hand at the sigmoid flexure and the other retracting the prepuce. If the ram is cast, sitting the ram upright and bringing the hind limbs towards the head can aid extrusion.

A study of 7307 rams at slaughter (Smith et al, 2012) demonstrated a prevalence of congenital urogenital lesions of 2.21%. Lesions recorded in the study include: testicular hypoplasia, microtestes, notched (or split) scrotum, hypospadias, cryptorchid, ectopic testis, scrotal hernia and epididymal lesions, such as segmental aplasia, cyst, blind efferent duct and sperm granulomas. Many of these abnormalities will affect fertility, but it is also important to consider whether animals with potentially heritable conditions should be used for breeding at all.

Any abnormalities detected during the reproductive examination should be recorded, along with their significance in terms of the ram's reproductive potential. Significance of these findings should be effectively communicated to the client.

Semen collection and analysis

Equipment

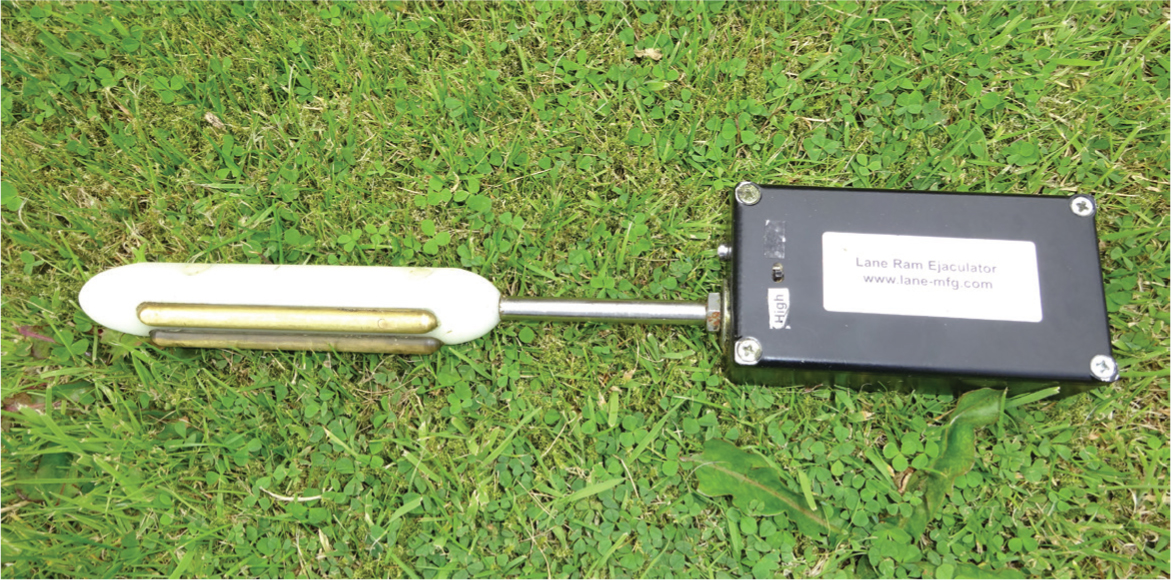

Electroejaculation, a commonly used method of obtaining a semen sample from rams, can only be carried out by veterinary surgeons. There are four commonly available types of electroejaculator available for ram semen collection:

The Ruakura-type probe has annular electrodes which also stimulate spinal nerves, leading to painful back and hind limb muscle stimulation. In the author's opinion, these should not be used on welfare grounds and their use has long been surpassed by the other types of probe. The ‘Lane pulsator V auto-adjust’ is commonly used for bull semen testing and can be fitted with a ram probe. The handheld ‘Lane ram ejaculator’ is the authors' preferred method of semen collection in rams as it is the fastest way to obtain a semen sample. In some countries, epidural anaesthesia is used to reduce pain or stress associated with electroejaculation (Abril-Sánchez et al, 2019) but this is not common practice in the UK.

Aside from the addition of a ram probe, the ram fertility testing box should contain the same as a bull testing kit (Table 3). A warm box is essential for semen analysis; a cost-efficient way of making a warm box is use of a polystyrene vaccine delivery box into which two 1 litre bottles filled with hot water (not boiling) are placed. To prevent cold shock, everything that comes into contact with the semen sample must be warm, but not too hot, as this will result in heat shock. This includes the use of a heated stage for the microscope. Heated stages can be retrofitted to any microscope (Figure 7).

| Warm box | Cold box |

|---|---|

| Microscope slides | Ram probe/lanes ram ejaculator |

| Microscope cover slips | Collection handle |

| Sharpie pen | Lube |

| Pipettes | Paper towel |

| Warmed phosphate buffered saline (PBS) | Clipboard, pre-breeding examination forms and pen |

| Warmed nigrosin-eosin stain | Scrotal tape measure |

| Slide containers | Microscope |

| Plastic collecting bags such as catering piping bags | Heated stage |

| Insulin syringes (for nigrosineosin stain) | Latex gloves |

Acquiring a sample

SVS recommends that routine electro-ejaculation and evaluation of semen provides appropriate additional information when rams are to be used in high pressure situations, such as single sire mating or with large numbers of ewes, but that it may not be appropriate in low pressure situations (SVS, 2014b). In the authors' opinion, a semen sample should be collected from all rams presented for a pre-breeding examination, as sub-fertile and infertile animals can present without any physical abnormalities. A study suggested that 9% of rams with no detectable physical abnormalities failed a pre-breeding examination due to a poor semen sample (Lovatt et al, 2014). Semen collection is possible using an artificial vagina (AV) but can be difficult and slow in stressed rams that are unused to being handled. It is often simpler, and much quicker to perform semen collection by electro-ejaculation, although the sample obtained may not always be a representative sample.

For electro-ejaculation, animals should be either haltered and/or manually restrained against a solid fence, or cattle stocks can be used (Figure 8). Rather than standing, some clinicians prefer to test rams in lateral recumbency. If using the ‘Lane ram ejaculator’, it is best used following the manufacturer's instructions which involves massaging the prostate 10 times with the probe, before then administering four seconds of current and resuming prostatic massage. This cycle should be repeated. In many cases, a sample is collected after only one or two cycles. If a sample has not been produced after four cycles, the ram should be rested and another attempt to collect a sample made at least 10 minutes later, often at the end of the group. The ‘Lane pulsator IV’ can be set to run on an automatic program as for bulls, but sample collection is much quicker when used in the same way as the ‘Lane ram ejaculator’ above. During semen collection, never provide more than 8 seconds of continuous stimulation, as per the SVS (2014b) guidelines.

Assessing a semen sample

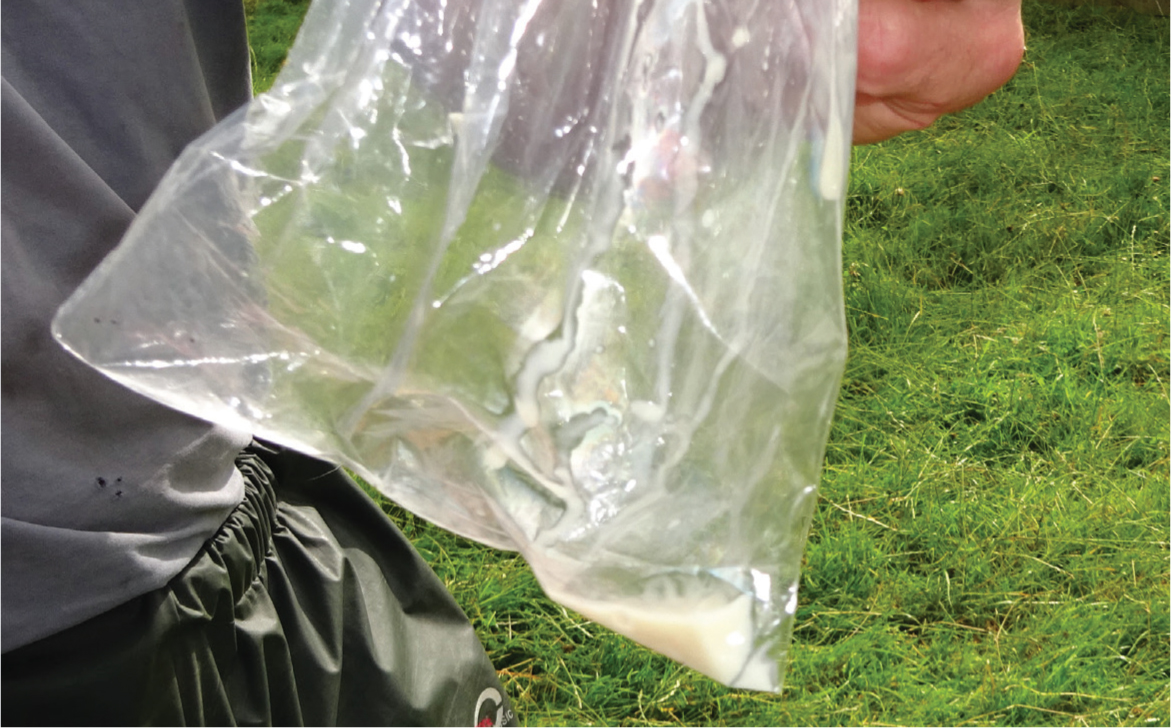

Once collected (Figure 9), the semen sample should be immediately transferred into the warm box and then evaluated for the following:

Gross density

Visual assessment of the density of the sample; the density should be graded on a scale of 0 to 5 (0 being water, 5 being thick cream) (Figure 10).

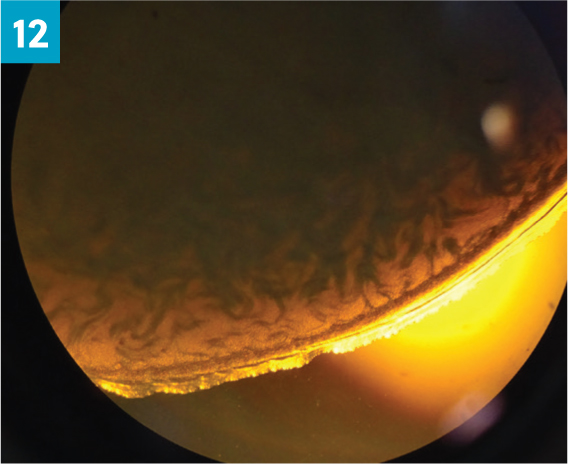

Gross motility

Assessment of wave motion of the sample under the microscope at low power (x10). One drop of semen is placed on a warmed microscope slide (Figure 11). Gross motility is again graded on a scale of 0 to 5 (Table 4) (0 being no activity, 5 being strong circular wave motion, or ‘looks like a pint of Guinness settling’) (Figure 12).

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dead | No Swirl | Very slow swirl | Slow distinct swirl | Pretty fast swirl | Rapid dense swirl |

| No sperm or all motionless | Some movement at edge of drop | -20-40% live sperm | -40-65% live sperm | -70-85% live sperm | -90% live sperm |

Progressive motility

Progressive motility is an assessment of the percentage of sperm cells actively going forwards in the diluted sample. One very small drop of semen is diluted with warmed saline and a cover slip is placed. Where saline is not available, use skimmed milk. The slide should be examined under medium or high power with the condenser at its lowest setting. Phase contrast is useful but not essential. There are advances in technology that aim to standardise progressive motility assessment, such as the Dynescan semen analyser, although these are not yet calibrated for ram semen.

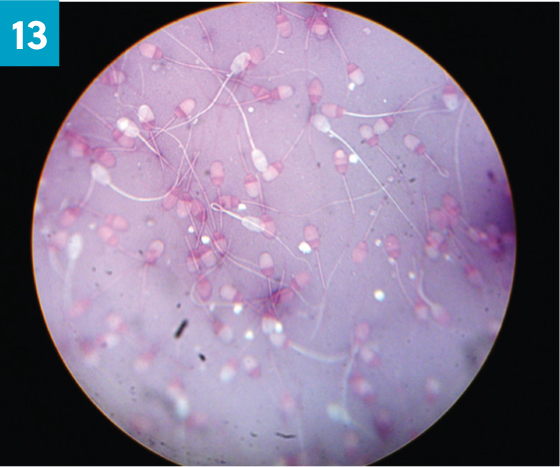

Morphology

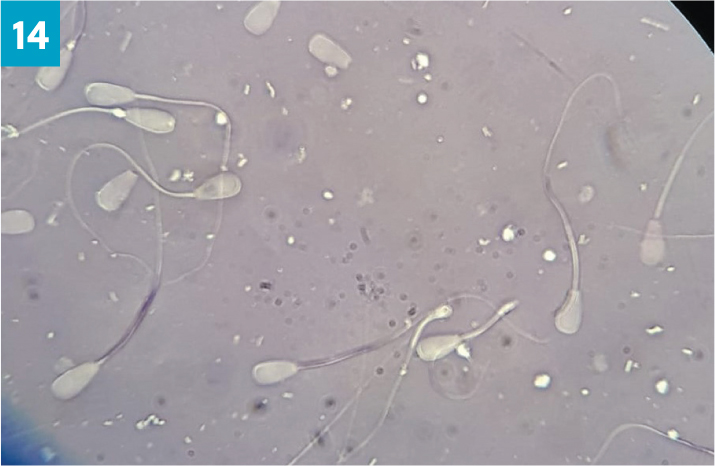

Ideally, every ram should be morphologically examined, however sometimes time constraints do not allow for this. In the authors' opinion, morphological assessment of ram semen need only be undertaken in high risk mating, such as single sire matings, or for further assessment when abnormalities have already been identified on examination. Morphology assesses the percentage of normal sperm cells and records the abnormalities found in the sample (SVS, 2014b). One very small drop of semen is added to two drops of nigrosin-eosin stain on a microscope slide, mixed and spread, similar to a blood smear (Figure 13). Once dry, morphology is assessed under oil immersion by counting 100 sperm cells and noting the number of deformities such as detached heads, micro or macrocephalic, nuclear vacuolation, knobbed acrosome, proximal cytoplasmic droplets, distal midpiece reflex and dag defects (Figure 14). Morphological abnormalities can be caused by a number of factors, including genetics, nutrition, thermal insult, stress, steroids and infectious agents (Petrovic et al, 2019). In bulls, the abnormalities identified can indicate the likely cause and time frame of the insult. Administration of corticosteroids or insulation of the testicles in bulls has been shown to lead to a sequential change in morphological abnormalities seen (Barth et al, 1994).

Further examination of the sample can take place if there are concerns about infection. Slides should be prepared by air drying and heat fixing, followed by staining with new methylene blue (similar to an anthrax slide preparation). Slides should be examined for the presence of leukocytes. The presence of large numbers of neutrophils would suggest an inflammatory condition that will affect fertility (Boundy, 1993). Collection of semen with the penis retained in the prepuce will result in greater likelihood of leukospermia relative to semen collection with the penis extended (Van Metre et al, 2012).

Classification: pass or fail?

To pass a ram, and therefore deem him fit for breeding, the semen sample must have a minimum score of: 2/5 for density, 3/5 for motility, with 60% progressive motility and with 70% morphologically normal (SVS, 2014b). Rams with a low score will be sub-fertile and inappropriate for single sire mating.

Further investigation

Rams that fail to produce a semen sample, or produce a poor sample, and in which no physical abnormalities are found, should be re-tested a minimum of 2 weeks later. No ram should be culled on a single poor quality semen sample if no other physical problems are detected. Masses should be further investigated using ultrasound with or without ultrasound-guided fine needle aspiration. Varicoceles, abscesses and spermatoceles can be diagnosed by ultrasound (Figure 15).

Libido

Pre-breeding examinations are not a diagnosis of libido. This should be explained and be recorded on the pre-breeding examination form. The prevalence of rams with same-sex partner preference has been estimated at 8% (Roselli and Stormshak, 2009). Synchronised cycling ewes can be used to observe libido and mating behaviours in the ram. Raddle marks can also be used as an indicator of libido, providing assurance that the ram is serving ewes in the first cycle.

Conclusions

Pre-breeding examinations of rams are a valuable management tool and an excellent opportunity to engage with sheep clients. This testing allows for improved efficiency and production by removing subfertile animals.