Digit amputation is a relatively common salvage procedure carried out in cattle (Desrochers et al, 2008), but it can equally be applied to small ruminants. This review is significantly based on the authors' own experience of performing this surgery in first opinion practice, as literature on the subject is limited.

Indications

In cattle digit amputation is indicated for septic pedal arthritis (infection of the distal interphalangeal joint) (Pejsa et al, 1998; Desrochers et al, 2008), pedal osteitis (infection of P3), toe necrosis (Blowey et al, 2011), non-healing solar and wall ulcers (Blowey et al, 2011), and indeed any painful, untreatable problem localised to the distal digit.

These same indications occur in small ruminants, but their relative frequency is different. The most common reason for digit amputation in sheep is septic pedal arthritis (Scott, 1995; Lovatt, 2012). This may originate from extension of infection from the interdigital space, from a penetrating wound affecting the distal interphalangeal joint or from infection elsewhere in the deep tissues of the foot. These cases present with extreme lameness (grade 3/3), and with swelling of the foot above the coronary band (Figure 1). This swelling is asymmetrical, with the affected digit being noticeably enlarged relative to the normal side. In some cases, especially chronic ones, there may be a discharging tract above the coronary band (Winter, 2004). This may be situated at the abaxial aspect of the coronary band, but the authors have also seen sinuses in the interdigital space, or at the caudal aspect of the foot. Unfortunately, affected animals often have a history of chronic lameness with multiple failed antibiotic treatments by the farmer (Scott, 1988; Lovatt, 2012). Where the condition is chronic there is often hair loss around the coronary band (Winter, 2004).

It is important to distinguish between a discharging tract from septic pedal arthritis, or infection of other deep structures of the foot, and the discharge of pus at the coronary band that occurs in cases of foot abscesses that ascend along the laminae (Clifton, 2021). In the latter, the degree of lameness is usually less (as once the pus has burst out the pressure is reduced and the animal is less painful), with reduced swelling of the digit above the coronary band. The appearance of the hole from which the pus discharges is different too. In the case of a foot abscess there is separation of the hoof horn from the adjacent skin, giving a ‘slot-like’ and proximally oriented aperture (Figure 2). Paring the sole will often help confirm the presence of white line disease, and the existence of a chamber associated with a foot abscess. By contrast, in the case of a discharging tract originating from septic pedal arthritis, the sinus is sometimes higher, it is rounder, and usually the aperture opens horizontally. There is usually hair loss and thinned skin around the sinus (Lovatt, 2012).

In goat herds where treponeme-related disease is present, cases of severe infection can occur (Groenevelt et al, 2015; Sullivan et al, 2015). These are characterised by areas of the loss of hoof horn and ulceration or erosions of the exposed corium. Some of these respond to systemic penicillin-based antibiotics and regular dressing changes. Among those that do not, especially when the problem is confined to a single digit, amputation should be considered. In the authors' experience, deep infection of the foot, with a discharging sinus in the interdigital cleft, was a feature of an outbreak of suspected treponeme-related disease in a goat farm.

Anaesthesia

Adequate anaesthesia is required for digit amputation. Local and regional anaesthetic techniques can be used to eliminate sensation of the distal limb, and are safe and inexpensive, and so are often used for this surgery (Hodgkinson and Dawson, 2007). The options include:

- Intravenous (IV) regional anaesthesia

- Local nerve blocks of the distal limb

- Ring block of the affected digit

- Lumbosacral or high-volume caudal epidural if the digit is on a hindlimb

- RUMM or brachial plexus block for a forelimb

- General anaesthesia (xylazine and ketamine, or inhalant anaesthesia) — general anaesthesia may be used alone or as an adjunct to local anaesthesia.

In the majority of cases the authors perform digit amputation either under IV regional anaesthesia or local nerve block of the distal limb, with physical restraint (Figure 3). General anaesthesia may be considered when local anaesthetic techniques appear to be ineffective, or cannot be applied for whatever reason.

Surgical method

Pre-operative administration of a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug and a broad-spectrum antibiotic should occur. The patient should be placed in lateral recumbency on a clean dry bed. When the digit in question is lateral, then the affected limb should be uppermost, when the affected digit is medial, then the animal should be placed so the limb is against the ground.

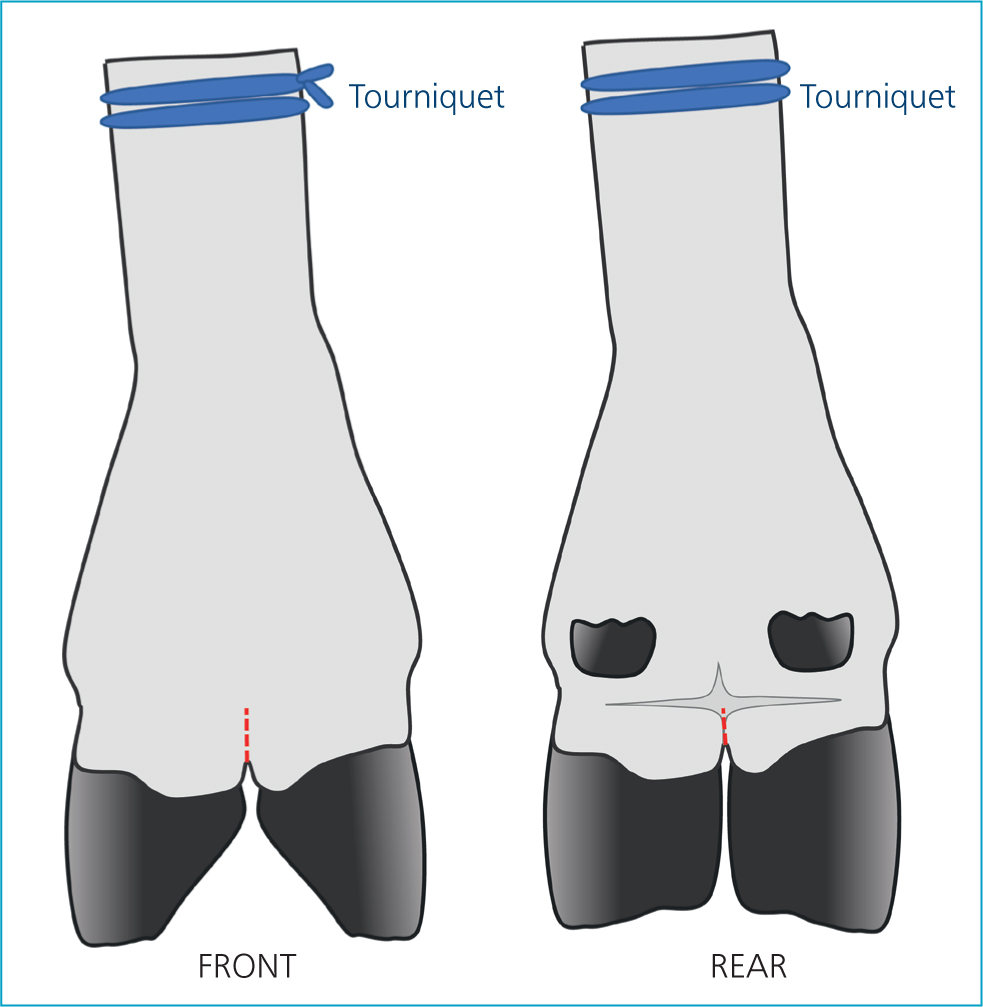

A tourniquet should be placed around the leg. Flutter valve tubing serves this purpose well. It is usually positioned just below the hock (rolls of bandage may be placed in the gutter either side of the calcaneal tendon) in the hindlimb, and just below the carpus in the forelimb. IV regional anaesthesia can then be performed if desired. Even if IV regional anaesthesia is not used, then a tourniquet is still recommended for intraoperative haemostasis.

If the limb is thickly-haired or wooly, then the section from the coronary band to above the fetlock should be shaved.

The limb from the fetlock down should then be cleaned as thoroughly as possible. As cleaning the hooves satisfactorily is often difficult, using adhesive bandaging material or the fingers from examination gloves to cover the hooves is recommended.

Once the surgical site is prepared, a surgical drape (or clean waterproof jacket), may be placed on the ground underneath the limb. An assistant can then steady the limb by pressing it against the ground. The surgeon can then scrub and proceed with the operation.

There are three main approaches to digit amputation in ruminants: disarticulation of the distal interphalangeal joint, bisection of P2 and section through distal P1. Disarticulation is discouraged as it requires the subsequently exposed cartilage of the articular surface of P2 to be removed (Osman, 1970; Desrochers et al, 2008). Also, if part of the synovium is left behind it will continue to produce synovial fluid which will delay healing.

In cattle, bisection of P2 is performed by placing Gigli wire in the interdigital space and cutting up at an oblique angle. The aim is to remove P3, the distal interphalangeal joint, and part of P2, while leaving the nutrient foramen of P2 undisrupted. Disruption of the nutrient foramen of P2 is likely to lead to necrosis of the bone and a more prolonged healing process, as resorption of the necrotic bone must occur (Osman, 1970).

Digit amputation by section of P1 involves cutting up between the interdigital tissues, and then cutting through distal P1 transversely, removing P3, P2 and the distal and proximal interphalangeal joints. Some authors advocate this approach in cattle (Heppelmann et al, 2009).

The respective advantages and disadvantages of the two methods are compared in Table 1.

Table 1. Respective advantages and disadvantages of the two methods for digit amputation

| Bisection of P2 | Transection of distal P1 |

|---|---|

| Does not require any instruments other than Gigli wire | Also requires a scalpel blade |

| Location and landmarks very obvious | Correct localisation of incision requires more attention and may be difficult if pastern area swollen |

| Removes only P3 and the DIPj | Removes P3, P2 and both DIPj and PIPj |

| Healing takes 5–8 weeks (Osman, 1970) | Healing takes 4–6 weeks (Osman, 1970) |

| Leaves small ligaments between digits intact | Disrupts small ligaments between digits, so reduced stability of remaining digit |

| Remaining bony fragment of P2 usually devitalised and undergoes resorption. Consequently, infection of the PIPj can result | Remaining fragment of P1 usually retains blood supply and so remains viable |

| If required by post-operative complications can always perform a transection of distal P1 subsequently | If P1 necroses and the MTPj becomes infected so that further amputation is required this necessitates disarticulation of the metatarsophalangeal joint, which is a more involved procedure |

Osman (1970) compared the healing process of these two methods in cattle, and concluded that transverse section of distal P1 had a shorter period to soundness, as there was a lower likelihood of bone necrosis.

In the light of this work, and given the smaller size of small ruminants, which makes the likelihood of overload of the remaining digit less, but accidental destruction of the nutrient supply to P2 in the distal approach higher, the authors favour section through P1.

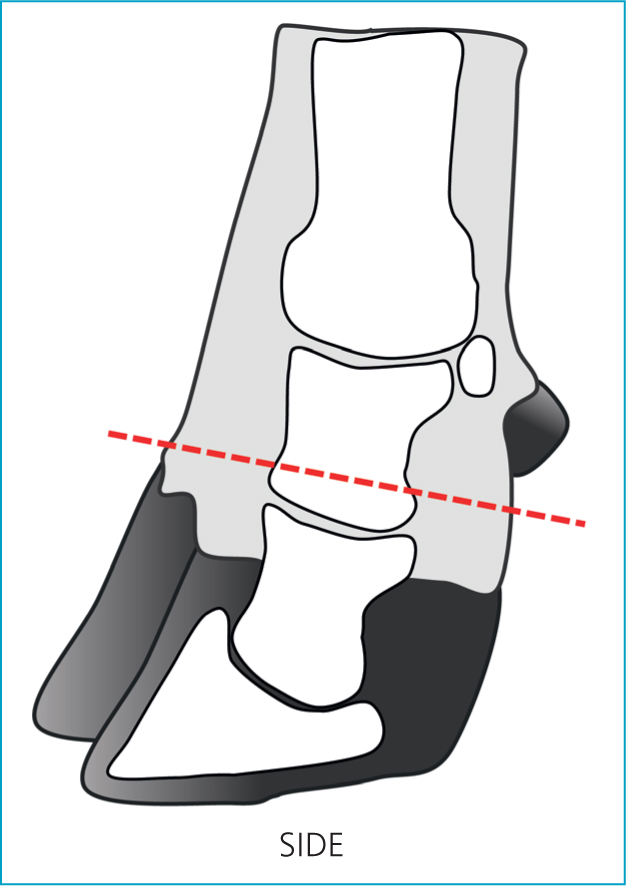

To achieve this reliably, the authors have found the following landmarks helpful:

- The plantar or palmar aspect of the foot is examined. There is a horizontal ridge of hair where the hair growth changes direction. This marks the upper limit of incision on the palmar/plantar aspect.

- The dorsal aspect of the foot is then examined. If the digit is flexed and extended, the location of the proximal interphalangeal joint can be determined. The upper limit of incision on the dorsal aspect is just proximal to this.

An incision is made through the interdigital skin and tissues, up to the levels of the landmarks described above (Figure 4). The Gigli wire is then placed in the resultant space, and the digit removed by cutting at right angles to the long axis of the limb (Figure 5). The limb may be stabilised by an assistant pressing it to the floor, or the surgeon's foot can be used. Stabilisation of the toe aids with this process.

After digit removal the cut surface should be flushed. If synovium remains it should be removed, as should any cartilage (e.g. if the cut has been performed too far distally). If infection of the flexor tendon sheath is suspected (rare) the tendon may be grasped with rat tooth forceps and a section exteriorised and removed to aid drainage. Any abscess chambers, drainage tracts etc, should be dissected out and removed.

A pressure bandage should then be applied. Given the nature of the tissue incised (often infected or inflamed), and the consequent contaminated nature of the surgery, the authors applied a dry-todry dressing with gauze swabs, which then debride when they are removed. The tourniquet should then be removed.

Aftercare

The first (pressure) bandage should be changed at 36–48 hours. Dressing changes every 4–7 days are recommended (by the authors) until there is a good bed of granulation tissue, no exposed bone or tendon, and wound contraction and re-epithelialisation are occurring. A non-adhesive dressing is recommended. At this point it is up to the judgement of the individual veterinary surgeon, based on conditions etc, as to whether or not they choose to continue dressing or manage the wound open; similarly with whether they decide to keep the animal housed or turn out. If the client is sufficiently knowledgeable, these bandage changes may be performed by the client themselves.

While the foot is bandaged the animal should be kept housed in a clean, dry, straw-bedded pen. The pen should be relatively small, and food and water should be in easy reach of the animal. The client should be instructed to contact the veterinary surgeon should the limb swell, a foul smell develop or the animal appear systemically unwell. If the dressing becomes wet or dirty it should be changed.

It is recommended that broad spectrum antibiosis be continued for 4–6 more days after the surgery, but this may need to be extended or the antibiotic choice adjusted in light of the appearance of the wound at dressing changes. Further pain relief may be required depending on the degree of pain the animal appears to be suffering (degree of lameness). (For further guidance on pain management in small ruminants see Adams, 2017)

Clients often remark on the immediate improvement in the degree of lameness post surgery, but this is because of the local anaesthesia. Those used to cattle digit amputations may be disappointed by the rate at which lameness reduces in small ruminants in the days immediately following digit amputation relative to cattle, but this might be a result of the relative differences in weight and the ease of movement on three limbs. It is usually expected that the animal will return to using the limb within a week or two, and that the dressing can be removed after 1 to 2 weeks. There is often no detectable lameness after 3 weeks (Figure 6).

Discussion

In cattle, digit amputation is usually considered a salvage procedure (Khaghani Borujeni et al, 2008), that is the aim is to get the animal to the end of lactation, or to slaughter weight, pain free and not lame, but not to retain in the herd longer, because of the lack of treatment options should the remaining digit become affected, and the theoretically greater risk of lameness caused by excessive weighbearing, i.e. sole ulcers, in the remaining digit. Heavier cattle have a poorer prognosis (Pejsa et al, 1993).

The same logic could be applied to small ruminants, however, it is common practice for farmers to retain animals in the flock or herd for prolonged periods after digit amputation. The authors have observed ewes and rams still in the flock up to 4 years after digit amputation, and does for 3 years. Sole ulcers are a rare cause of lameness in sheep and goats (Aguiar et al, 2011), and so one of the arguments for culling is removed.

Arthrodesis has been suggested as an alternative to digit amputation (Lovatt, 2012), with the advantage that the affected digit is retained. However, it requires more skill to perform, the postoperative care involves repeated flushing of the joint by an indwelling catheter, which requires a hygienic environment, and if unsuccessful (e.g. a result of a failure to remove pannus and nidi of infection by flushing, or pedal bone osteitis, or too much damage to the ligaments of the distal interphalangeal joint) then recourse to amputation is required anyway. Reports from the literature are limited, but suggest a longer time to return to soundness (Lovatt, 2012).

In cattle, alternative approaches of toe amputation or curettage and irrigation have been suggested for infection confined to the pedal bone (Grisiger and Martin, 1996).

In terms of the cost-benefit of digit amputation, the procedure can be performed within 20 minutes, and if the farmer is happy performing the bandage changes, then only a single veterinary visit is required.

In some countries leaving animals with septic pedal arthritis for arthrodesis to occur is advocated (West et al, 2002), but this involves 3–6 months' severe lameness, and there is no guarantee it will be successful, especially as other infectious conditions of the digit may appear similar to septic pedal arthritis. Such an approach is unacceptable (Figure 7).

Where farmers present animals affected by infections of the deep tissues of the digit, the decision must be made whether these animals are to be treated correctly (i.e. surgically — whether by amputation or joint lavage) or are to be euthanased on welfare grounds.

Conclusion

Digit amputation of small ruminants is a relatively simple procedure that is recommended for septic pedal arthritis and other deep infections of the digit. In the authors' experience, it is best performed through transection of distal P1. Postoperative care is relatively simple, and recovery time is more rapid than alternative procedures. The value of animals as breeding, draft or store animals will fall after digit amputation, but they can remain in the flock or herd as productive animals for several more years, or can go for slaughter.

KEY POINTS

- Digit amputation is a relatively simple surgical procedure that is indicated by infection of the distal interphalangeal joint, pedal bone or other deep structures of the foot.

- Digit amputation may be performed under local, regional or general anaesthesia.

- The authors prefer transection of distal P1 to bisection of P2.

- Postoperative care involves a pressure bandage for 36–48 hours, and then regular dressing changes (every 4–7 days) for 1–2 weeks.

- Animals will usually begin to use the leg again after 1 week, and full resolution occurs within 3–4 weeks.