References

Udder cleft dermatitis: a review

Abstract

Udder cleft dermatitis (UCD) is a common skin condition of dairy cows characterised by ulceration, tissue necrosis and a purulent, foul-smelling discharge. The lesions can be severe, and the herd prevalence is usually underestimated by farmers as milder lesions are often not detected. The condition is thought to occur as a result of opportunistic bacterial infection following physical abrasion in an anaerobic environment. A weak fore udder attachment and deep udder are associated with an increased risk of UCD. Culling and selective breeding to improve udder conformation within the herd are important for prevention of the condition. Treatment of severe lesions is challenging and as such early identification is critical along with repeated treatment applications.

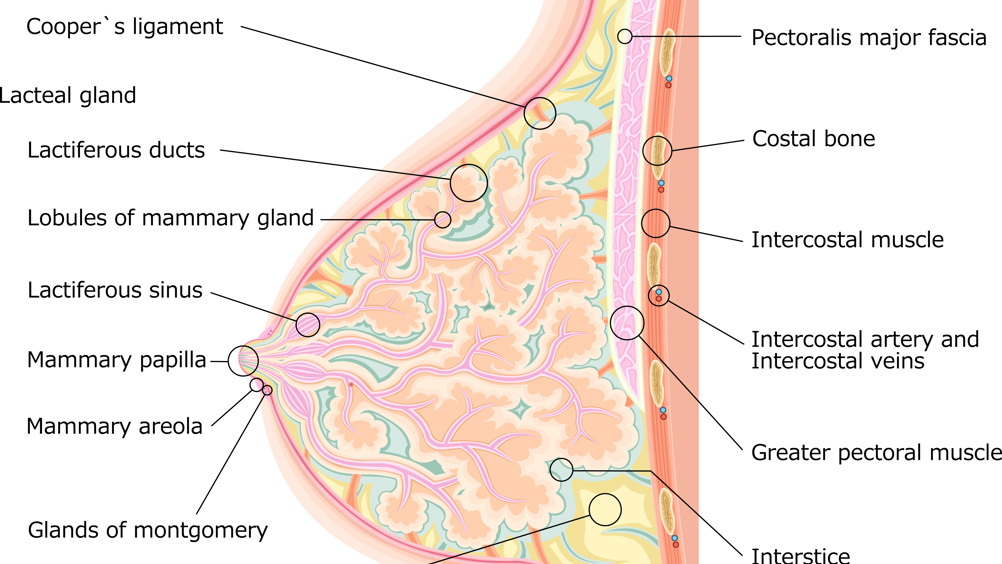

Udder cleft dermatitis (UCD), also known as udder intertrigo or ulcerative mammary dermatitis, is an endemic disease of dairy cows. It occurs at the cleft of the fore udder attachment, between the two halves of the udder or between the udder and the thigh (Figure 1). It is characterised by a moist, exudative dermatitis with a foul odour and was first reported in the UK over 20 years ago (Beattie and Taylor, 2020). These sites are prone to ulceration and necrotic skin can promote the growth of bacteria, leading to deep, persistent infections.

Treponemes similar to those causing bovine digital dermatitis (BDD) have been identified in UCD lesions (Stamm et al, 2009; Evans et al, 2010). However, they were not present in all lesions and some strains showed variation from those associated with BDD. This leads the authors of these studies to the conclusion that BDD and UCD did not share a common infectious cause. More recent research has characterised the bacterial flora of UCD lesions in more detail (van Engelen et al, 2021). The anaerobic bacteria Trueperella pyogenes and Bacteroides pyogenes, which are commonly associated with conditions such as secondary skin/wound infections, abscesses and metritis in cattle, were found to be the most common bacteria present in severe lesions. This study found no evidence of treponemes, common mastitis pathogens or mites in any of the 128 samples examined. No evidence has been found for a specific infectious cause of UCD, suggesting that it is more likely to be associated with a combination of skin trauma and an anaerobic environment within the udder cleft leading to an opportunistic bacterial infection.

Register now to continue reading

Thank you for visiting UK-VET Companion Animal and reading some of our peer-reviewed content for veterinary professionals. To continue reading this article, please register today.